Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

OLIVER MATUSCHEK

THREE LIVES

A BIOGRAPHY OF

STEFAN ZWEIG

Translated from the German by

Allan Blunden

P

USHKIN

P

RESS

L

ONDON

Contents

Introduction Three Lives in Retrospect

Trials and Tribulations of a Writer

THREE LIVES

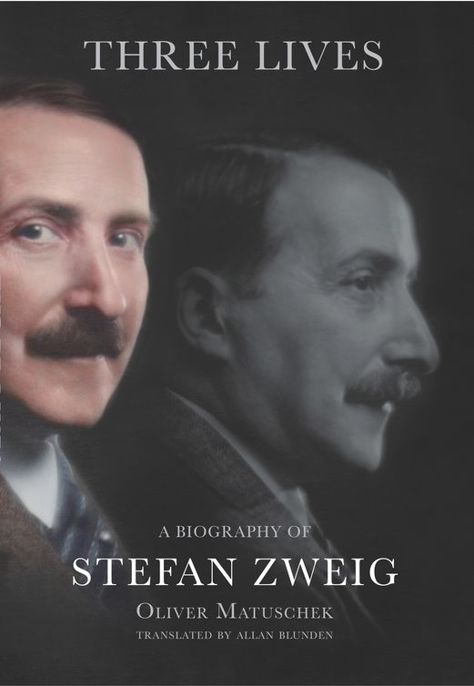

Stefan Zweig (left) with his first wife Friderike Maria and his brother Alfred, photographed in Bad Gastein in the summer of 1929

The outward impression that one gets of this singular man blurs many a notion that one has formed of the writer Stephan Zweig. A meeting with him is in no sense a disappointment, it is just very different from what one expects. His demeanour is so cautiously reserved and unassuming, that in conversation about ordinary everyday things one forgets about the powerful and vigorous language of his short stories and novels, his poems and plays. One is quite won over by the enchanting simplicity of his appearance and character.

1

Egon Michael Salzer in the

Neues Wiener Journal

August 1934

In July 1940 the journalist H O Gerngross met in New York with one of the most famous European writers of his day, Stefan Zweig. The two men talked about times past and future plans, about brilliant successes and dark forebodings. With the

Anschluss

of 1938 Zweig’s native Austria had been incorporated into the German Reich; his books were banned in both countries, and as a Jew he could not even think about returning home. At the time of the interview the Second World War had been raging for almost a year, and the Netherlands, Belgium and northern France had just been occupied by the German

Wehrmacht

.

Despite all the setbacks and defeats, Zweig planned to carry on devoting all his energies to writing and producing new books for his reading public, even if that audience was a great deal smaller now in Germany as a result of the book bans. The journalist Gerngross tells us that he saw “on the little writing table in the hotel room and on the chair next to it, [ … ] sheets of paper, squared sheets of paper from an ordinary tear-off pad. They are covered with that neat, elegant handwriting that we know so well. And the purple ink is still there.” In the preceding decades Zweig had penned thousands of manuscript pages and letters in this, his preferred shade of ink. But now he was preparing a work of a different kind. As Gerngross reveals to his readers:

Stefan Zweig is taking a break from literature and belles-lettres. A biography of Balzac, planned for many years, remains unfinished, not least because the author is now denied access to the archives in Paris. The novella (a form of which Zweig is the master) no longer seems to him the right form of expression for today, because of its preoccupation with the problems of the individual. And yet he is currently writing the most personal book he has ever produced—the story of his life. He has already decided on a title for this autobiography:

My Three Lives.

2

And in due course Gerngross published his article in the émigré newspaper

Aufbau

under the title ‘Drei Leben’. Looking back on his life story, Stefan Zweig viewed it in terms of three distinct phases. The first life, which had begun in 1881 with his birth as the son of a weaving-mill owner in Vienna and ended with the First World War, had been lived in the seemingly secure world of the affluent bourgeoisie. His second life had begun, full of hope, in his new elective home of Salzburg, and had brought him an unparalleled rise to eminence as one of Europe’s most widely read and translated authors, before ending with his departure from Austria. His third life, which he spent in exile, had not long begun at the time of the interview: it would turn out to be the shortest of the three.

As he was writing his memoirs Zweig soon realised that he was not really telling the story of his life, but rather painting a panoramic picture of the age. Many of his own experiences are woven into the narrative, but his private life as such is completely glossed over. His two wives and some of his closest friends do not get a single mention in the entire manuscript. So the intended title now seemed less appropriate than originally thought, given that a book entitled

My Three Lives

would clearly have led readers to expect a much more personal account than the one Zweig had actually written. In the end the work appeared after his death as

Die Welt von Gestern

—the final (and very appropriate) title chosen by the author.

For any examination of Zweig’s life—including the present study, therefore—his own book of memoirs is clearly of central importance. But for anyone who wants to understand not only the writer and contemporary observer Stefan Zweig, but also the man and his private life, in order to paint a more accurate picture of his “three lives”, there is now a wealth of published material available, starting with the collected edition of his works and diaries, and including various volumes of letters and exchanges of letters from the vast correspondence that Zweig conducted throughout his life. And yet many questions remain unanswered. The much-quoted words “Your writings, after all, are only a third part of who you are” appear in a letter written to him in 1930 by his first wife Friderike. The passage in

question reads like a daunting warning to anyone bold enough to research the biography of Stefan Zweig: “Thinking yesterday about your friends, it troubled me to think that nobody—apart from me—really knows you, and that one day the most fatuous and foolish things will be written about you. But then you let very few people get close to you, and when it comes to the real you, you are a closed book—and understandably so. Your writings, after all, are only a third part of who you are, and nobody has managed to extract from them even the bare essentials needed to understand the other two-thirds.”

3

It is true that even in his younger years Stefan Zweig rarely spoke openly about himself. Even to people who knew him well he came across as buttoned-up, and in many ways he remained a riddle even to his close friends. But happily Friderike did not keep her knowledge to herself. In addition to a number of historical accounts she also wrote several books of memoirs in the post-war years, which contain important clues and aids to interpreting the life and work of her former husband, and which have played—and continue to play—a key role in biographical research. Her book

Stefan Zweig, wie ich ihn erlebte

[

Stefan Zweig as I Knew Him

] was published in German as early as 1947. Five years later, following numerous shorter newspaper articles and interviews, extracts from the correspondence they had conducted between 1912 and 1942 were published in book form. Friderike Zweig was now living in the USA, where she died in 1971, but over the years she visited her former homeland on several occasions, giving lectures in Vienna and other places and reading from her works at well-attended literary events. In 1961 her book

Stefan Zweig—Eine Bildbiographie

[

Stefan Zweig—A Biography in Pictures

] appeared, followed three years later by

Spiegelungen des Lebens

[

Reflections of Life

], which is more of an autobiographical work, although several important chapters are devoted to Stefan Zweig.

As we now know, Friderike Zweig’s publications are tainted by a blend of more or less adroit manipulation and concealment of facts (and this for more or less understandable reasons). The first thing to say is that she never wrote her accounts with the intention of producing works of scholarship, but instead recounted her memories in the style of fictional narrative, with an eye to the interests of her readers. And for many of the events she described she no longer had much, if indeed anything, in the way of documentary sources, so that she was forced at times to rely on her own memory. Consequently it is easy to understand how errors have crept in when describing events that took place in some cases

several decades earlier. More problematic are the instances of deliberate interference with existing texts, where Friderike has arbitrarily removed references to particular individuals or qualified certain statements without any acknowledgement—even though she specifically states, in the foreword to the published edition of the correspondence, that no changes have been made to the original text of the letters. The substitution of the occasional expression, as for example when the derogatory Austrian term “Piefkes” in one of Zweig’s letters becomes “Reich Germans” in the printed version, may well be a useful aid to understanding for many readers;

4

but the extent of the manipulation goes far beyond such minor emendations. In particular those passages where Stefan Zweig’s second wife Lotte was mentioned fell victim to Friderike’s censorship. As nearly all the known letters have survived, many problematic passages have now been revised and the original versions used as a basis for the present biography.

5

Like the published correspondence, Friderike’s volumes of memoirs also proved quite popular with the reading public, and only a few individuals were in a position to voice informed criticism of their reliability at the time of their publication. One such person was Stefan Zweig’s elder brother Alfred, who had left Vienna in 1938 and settled in New York, where he lived until his death in 1977. The walls of his apartment overlooking Central Park were hung with numerous photographs of family members. Many of these pictures showed his famous brother Stefan, who had committed suicide in 1942 together with his second wife Lotte. Far from his European homeland, Alfred not only had to contend in the post-war years with repeated and thoroughly objectionable questions from every possible quarter about his brother’s Communist activities (since people were constantly confusing Stefan Zweig with Arnold Zweig), but also had to fend off other attacks as a result of Friderike’s activities.

It should be said at this point that relations between Alfred Zweig and his sister-in-law Friderike had never been particularly good, let alone cordial. But by the time she published her memoirs the relationship had become openly hostile. Alfred saw every single book that Friderike wrote as a direct attack on members of his family. Here was this woman, presuming to give a detailed account of her former husband’s childhood and his life in the family home, as if she had been there and seen it all in person—whereas she had not even met Stefan properly until he was thirty. Furthermore she described his father as “sickly” and the mother as “wilful”, in order to cast

herself as some kind of redeeming figure in the story of her husband’s life, while at the same time suppressing details of their life together in Salzburg, which had had its fair share of tensions and conflicts.

In many of her observations about Stefan’s family there may well have been a grain of truth, but Alfred steadfastly refused to accept her accounts as they stood. He was not interested in writing a book of his own to set the record straight, and legal action would probably not have achieved anything. But he stated his views on Friderike’s books at every available opportunity, commenting on and correcting her claims wherever he could.

It was not just Friderike’s written pronouncements that so incensed Alfred—her behaviour in general prompted a waspish response from him on many occasions. During the post-war years, for example, Friderike consistently made herself out to be Stefan Zweig’s widow, a claim that was entirely without foundation and wholly false. Their marriage had been legally dissolved in November 1938, and even though Stefan had expressly permitted, and indeed desired, that Friderike should continue to use his surname, she was unquestionably his divorced wife from that time onwards. But even in her certificate of naturalisation for the United States, which was issued on 9th June 1948, her family status is officially listed as “widow”. None of this would really be worth mentioning, had Friderike not used this false declaration to try and suppress and cover up the fact that Stefan Zweig had remarried after their divorce. But since his second wife had died with him in a suicide pact, the role of widow remained vacant, so to speak—until Friderike came along to fill it. For Alfred Zweig this was a morally repugnant piece of behaviour, which could only strengthen him in his determination to set his own truth against Friderike’s version of events.