Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (3 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

The wedding had taken place in September 1878, and on 13th October of the following year the first child of this unequal couple was born in Vienna. It was a boy. Given the name Alfred, he promptly assumed the role of heir apparent—to stick with the dynastic metaphors—because it was already clearly understood that this boy, health permitting, would one day take over the running of the family business.

A little over two years later, on 28th November 1881, in the family’s apartment at Schottenring 14 in the 1st District, a second child was born. It was another boy, and he would be called Stefan.

A matter of days after he was born there was a major incident in Vienna that sent a shockwave of horror through the city. On 7th December escaping gas from the stage lighting in the Ringtheater caused fire to break out during a performance of Jacques Offenbach’s opera

Tales of Hoffmann.

The decision to evacuate the building was taken much too late, and the operation was severely hampered by the fact that the doors of the auditorium only opened inwards. As a result of this serious design fault the doors were jammed shut by the jostling crowds, and in the ensuing panic as people tried to escape, appalling scenes of carnage were witnessed. Estimates of the number of dead range between three hundred and five hundred. The Zweigs were particularly affected by these events because their apartment overlooked the theatre, so that the disaster unfolded literally before their eyes. They looked on aghast as the flames took hold and the chaos spread. With that strange mixture of helplessness and fascination that those who observed the disaster must have felt, the parents even fetched Alfred, then just two years old, to watch from the windowsill. He later said that the images of the blazing building were his earliest memories.

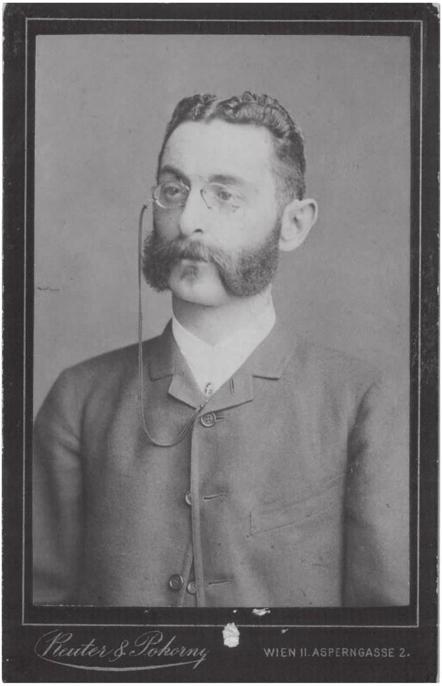

Moriz Zweig

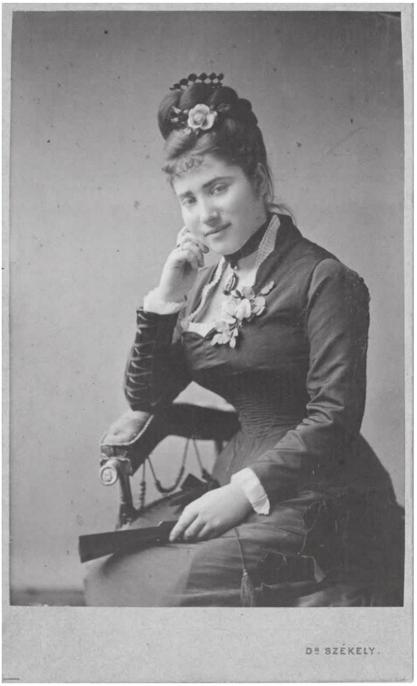

Ida Zweig

Ida Zweig’s second pregnancy had run its course without any notable problems, but following the birth of the child she was found to be suffering from a severe hormonal imbalance. Not long afterwards she fell ill with sclerosis of the middle ear. This insidious condition, which can be caused by hormonal factors, manifests itself in a chronic inflammation of the tympanic cavity, which causes sclerosis of the mucous membrane and disrupts the delicate mechanism of the ossicles so that they can barely function, if at all. Since the onset of deafness was gradual, the doctors and their patient initially underestimated the seriousness of the disease and its possible repercussions. After some lesser problems, Ida Zweig’s hearing faded rapidly and irretrievably in just a few months; medical science had not yet devised an effective therapy or surgical procedure. The young wife soon needed an ear trumpet to follow conversations, and attending larger social gatherings became a test of her patience and powers of concentration. All thought of going to concerts, operas and theatre performances had to be abandoned. But in due course a pleasurable alternative presented itself—after initial scepticism, she developed a lifelong passion for the cinema, where the silent films of the day could be understood perfectly well even without the musical accompaniment.

Despite her handicap, Ida Zweig retained her essentially cheerful temperament throughout her illness. But as a result of the deafness her more contrary inclinations became more pronounced. Normally fairly placid by nature, she could erupt into terrifying rages if pushed too far. She was always seen as something of a curiosity among her social acquaintance—and not just because of her illness. Added to that, it must have seemed quite odd to some outside observers in those days that she frequently served such exotic dishes as risotto and artichokes at her table—in memory of her native land.

For almost the entire year she kept her more valuable jewellery in a safe (where most of it went missing in 1938), ordinarily wearing just some modest brooches, rings and necklaces. She dressed relatively plainly for everyday wear, but always in a manner that befitted her station, of course. Ida Zweig was not a conspicuously elegant lady, but until 1914 she remained a customer of the city’s foremost dressmakers; and doubtless she was also a familiar visitor to the shop on the ground floor of the building where they subsequently lived in the Rathausstrasse, which traded in furs “

En gros et en détail

”, as the sign above the entrance proclaimed.

As the wife of a mill owner she had assembled a circle of acquaintances around her who regularly met for tea. But it would be an exaggeration to describe this as a “salon”. The Zweig family home was frequented not by

composers, painters, actors and writers, but rather—much as one would expect—by lawyers, industrialists and bankers of their acquaintance, together with their wives. Looking back in later years Alfred Zweig described them as “Jewish bourgeoisie of the first rank throughout”, adding that the family always maintained its distance from Christian social circles, as was the unspoken rule in Vienna.

4

The fact that the family was Jewish was neither denied nor particularly emphasised. Stefan’s birth had been registered under the serial number 1968 for the year 1881 by the Jewish religious community, but so far no documents have come to light that would enable us to determine what role, if any, the Zweigs played in the life of the Jewish community. And the testimony of family members gives us hardly anything to go on here. The family no doubt attended the synagogue for the main Jewish feast days and festivals but at home in December neither the Jewish Festival of Lights, Hanukkah, nor the Christian Christmas was celebrated. The latter was entirely normal in other Jewish families who had moved away from their faith. The only concession to the season was a small Christmas tree decorated for the servants—and presents were also given to the domestic staff, to the enormous chagrin of the two Zweig boys.

In material terms the boys wanted for nothing. To the extent that they spent time with the children themselves, the parents took great care to treat them both equally. But for most of the time the two boys were entrusted to the care of a nanny. In fact, in what is probably the earliest photo of Stefan, taken when he was around nine months old, he is seen not with his mother or both parents, but with his Slovakian nanny Margarete. In the years that followed the two brothers had their photograph taken frequently. The velvet suits with the enormous-looking bows knotted around their necks, which they are wearing in one of the photos, were probably their—not very comfortable—everyday wear. Stefan in particular, with his round face, chestnut-brown hair and big, dark eyes was regarded as an adorable child by those who had not witnessed one of his feared temper tantrums. On one occasion, indeed, a member of the Austrian imperial household stopped her carriage in order to speak to the sweet little boy who was walking in the park with his father—a memorable occasion that went down in family history.

In 1886 the Viennese painter Eduard Kräutner was commissioned to paint a portrait of Stefan in his sailor suit with an anchor embroidered on the chest. The oil painting he produced for the parents was almost a

photographic likeness of the boy. Only his faint smile had been brought out a little more strongly by the artist, an experienced practitioner of his craft, who produced hundreds of these portraits.

Since Ida Zweig’s hearing difficulties often left her a little disconnected from everyday family life, her mother was more than happy to step in when needed to help with the children’s upbringing. When the family moved in 1895 from the Schottenring to a larger apartment at Rathausstrasse 17, Grandma Brettauer, who had lost her husband in the meantime, lived in the neighbouring apartment on the same floor, so that she was now very close to her two grandsons in every sense. Alfred Zweig remembers her as a “very capable Bavarian

Hausfrau

of the old school, [who] knew everything there was to know about looking after children, especially when they were ill”.

5

Despite her down-to-earth manner, she too exhibited all the inborn snobbery of the Brettauers. Even as a grown man and a world-renowned writer known by the Zweig family name, Stefan would come up against the self-regard of his relations on his mother’s side: “This pride in coming from a ‘good’ family was deeply ingrained in all the Brettauers, and if one of them in later years wished to show me special regard he would remark, condescendingly, ‘You’re a true Brettauer at heart,’ as if to say to me approvingly, ‘You turned out all right.’”

6

Still, his unusual profession (and not least, no doubt, its unexpectedly lucrative earnings) had earned him the highest respect even in this branch of the family.

For all the care lavished on the boys by their grandmother, their upbringing was really the responsibility of the governess specifically appointed for the task. In the years before Alfred entered grammar school, the Swiss governess Hermine Knecht was the two boys’ constant companion. Little is known about these years in Stefan’s life, but many of his childhood experiences must have consciously exercised him for many years to come. At all events, for Zweig the writer they later became an almost inexhaustible source of material for new stories. In the collection

Erstes Erlebnis—Vier Geschichten aus Kinderland

he presented his readers with a series of tales in which anyone who knew about the author’s origins could probably detect autobiographical influences of one sort or another. Even Alfred Zweig thought he recognised many similarities with his own family home.

Admittedly it was not so much the agreeable aspects of childhood that yielded material for psychologically interesting characters. The stories in the collection are prefaced by a poem that in its very first verse conjures up a mood of dark melancholy:

O childhood, how oft I stood behind your bars,

Confined, imprisoned, and in tears,

While outside, on wings of blue and gold,

Soared the great bird Unknown.

7

One already senses that attempts to break out of this cosseted and doubtless also boring world promised more excitement, in any case, than the dull daily round, with its formal etiquette and velvet suits.

The boy called Edgar, who appears in this collection as a character in the story

Brennendes Geheimnis,

has also been seen often enough—and surely with good reason—as Zweig’s “doppelgänger from those early days”,

8

a view endorsed by his friend Erwin Rieger in his authorised biography of Zweig. Yet we should beware of seeing overly direct parallels, because it is more the atmosphere and the details, rather than the actual narrative content, which mirror the family’s life during those early years in Vienna. For example, the nightly injunction

“Neuf heures! Au lit!”,

9

delivered in affected tones by Edgar’s mother at nine o’clock to indicate that it is time to go to bed, was no doubt not unfamiliar to Alfred and Stefan Zweig, given that French was spoken in the family home on a routine basis. If their mother, aunt and grandmother were having a conversation which they did not want the children or servants to understand, they would simply slip into Italian without missing a beat. The same thing happened when they got together with other family members, as Stefan later recalls apropos of a visit to an aunt in Paris.

The summer months brought a special change of scene, as the family went away on holiday. The first half of the holidays was normally spent in Marienbad, where Ida Zweig went every year to take the waters. On these occasions it was not just the small family of four that made the journey, for they would be accompanied by a small entourage consisting of at least one male and one female servant for the parents as well as a governess for the children. Following the death of her husband, grandmother Brettauer quite often travelled with them, bringing along her own domestic servants. In Marienbad the family party normally took rooms in the luxurious Hotel Gütt or in the Fürstenhof, taking easily to the social life of the town, with its daily round of therapeutic treatments and spa concerts.