Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (2 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

Of course Alfred had his own interest in protecting his family and himself, so that the pendulum often swings too far the other way in his portrayal of events—which should not be forgotten when relying on his account. In his will he had instructed that all family papers in his possession along with any of his brother’s remaining letters should be destroyed after his death, which is evidently what happened, with one or two exceptions. In preparing the present study, however, the author has had extensive access for the first time to unpublished correspondence of Alfred Zweig’s, which survives in three large bundles of letters running to several hundred pages. These comprise the following:

—The letters that Alfred Zweig wrote to Stefan’s heirs and his second wife Lotte. Many of them deal with issues relating to the family fortune and the management of the weaving mill once owned by the Zweigs, which had brought them a measure of affluence and of which Alfred had been the director.

—Letters to Richard Friedenthal, who had been a friend of Stefan’s, and later took on the task of managing his literary estate. For a long time Friedenthal was planning to write a substantial biography of Stefan Zweig, for which Alfred supplied a great deal of inside knowledge and material; more especially he furnished a commentary on Friderike’s writings aimed at correcting what he saw as misrepresentation. Despite amassing a great deal of material and doing extensive spadework, Friedenthal never did get round to starting the book.

—The correspondence with Erich Fitzbauer, who had founded the International Stefan Zweig Society in Austria in the late 1950s and dedicated himself to its work. Here too Alfred supplied important information about the history of his own family and the biography of his brother, even donating a number of original private documents to the Society.

The attempt to discover new facets to our picture of Stefan Zweig and his immediate circle was also greatly assisted by the active support of his heirs, who agreed to talk about their personal memories for the purposes of this project, and also granted access for the first time to letters written by Lotte Zweig. Stefan Zweig’s literary estate, including source materials and extensive preliminary studies for his Balzac biography, other manuscripts and notes (in part unpublished) as well as thousands of letters written to him by famous or well-known contemporaries, had already been given by his heirs, in successive stages, to the Reed Library at the State University of New York in Fredonia, so that the present study was also able to draw on this material.

In addition, various original documents in private collections and in other public libraries and archives from London to Jerusalem, from Switzerland to the USA, and from Austria, Germany and Brazil have also proved to be valuable sources. The research for this book turned up many an unexpected find—such as the transcript of a television interview that Zweig gave to the BBC in London in June 1937. Previously the only record of this event was a photograph showing him facing the camera in the studio, but the questions and answers had in fact been transcribed at the time, whereas the broadcast itself—one of the earliest television programmes

made—went out live, and was not recorded. The present volume is also illustrated with photographs found in some of the albums from Alfred Zweig’s estate that had escaped destruction. Some of them are published here for the first time, and form a fascinating addition to the other photographs from private and public collections reproduced in these pages.

In many instances the new information gleaned from the wealth of additional source material only affects matters of detail, but sometimes it has helped to fill in some of the larger missing pieces in our picture of Stefan Zweig. Certainly his family, whose individual members played key roles in his ‘three lives’, can now be portrayed in much more detail than has hitherto been possible. Here, then, was an opportunity to paint a personal portrait of Stefan Zweig the man, and of his “three lives”, without losing sight of one of the most successful writers of his time. As Zweig himself once put it, on the threshold of a new literary endeavour: “Let us put it to the test.”

6

NOTES

1

Salzer 1934.

2

Gerngross 1940.

3

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 18th July 1930. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 228.

4

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Zweig, 12th August 1925. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 1951, p 189 (here incorrectly dated 3rd August 1925). Compare the version reprinted in Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 174 f.

5

A completely revised and annotated edition of a portion of the correspondence between Stefan and Friderike Zweig (Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006) has since been published.

6

10th September 1912, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 9.

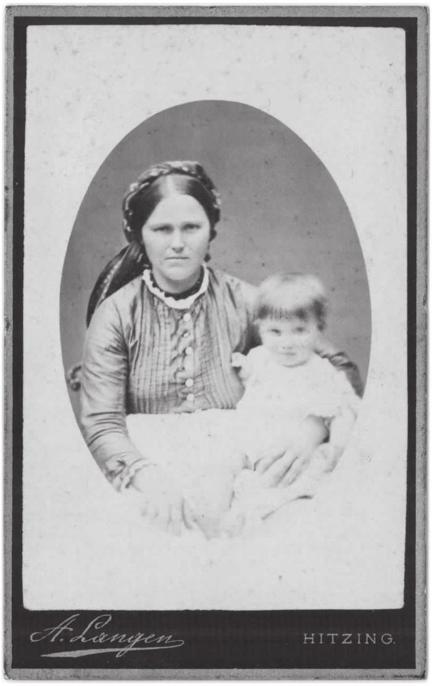

Stefan Zweig with his nanny Margarete

If I were to gather together my own childhood experiences, they would have their share of sunshine and clouds; but they would lack that clear, calm radiance that rustling Nature has shed upon you. The lot of a city dweller can be just as tragic, and yet never as great!

1

To Hermann Hesse 2nd March 1903

O

F ALL THE PEOPLE

in Stefan Zweig’s family and immediate circle during the early decades of his life, the figure of his father emerges as the least sharply defined. Only one letter of his has ever come to light, other documents written in his hand are virtually impossible to find, and even in the stories told by the family he nearly always plays a secondary role. The surviving photographs only serve to confirm the impression of an unremarkable man: in a whole series of portrait photos in the popular

carte de visite

format, taken at intervals over several decades, Moriz Zweig cuts a consistently unimposing figure. Neither his pose nor his expression changes, despite the long intervals between photographs and the different photographers involved. Only the cut of his beard alters in line with changing fashions—and his face looks a little more tired from one picture to the next.

Moriz Zweig was born on 28th December 1845 in Prossnitz in Moravia. The spelling of his first name varies: in the printed announcement of his engagement and on his gravestone it is spelt “Moritz”, while in the obituary published by the family we find “Moriz”. As he himself wrote “Moriz”—when countersigning his son’s school reports, for example—and the name is also spelt thus in all official documents, this is the form that we shall use here.

2

The family history records the Zweigs as resident in his birthplace since the middle of the eighteenth century, but in all probability they had been living there for much longer. His father Hermann, like his ancestors before him, traded in assorted goods—in particular textiles—on a growing scale and over an ever wider area, and in 1850 he took the plunge and moved from the provincial town to Vienna, together with his wife Nanette and the rest of the family. Here Moriz attended the upper secondary school, learnt French (eventually becoming completely fluent

in the language) and a little English. Following the Zweig family tradition, he became a trader in textiles when he left school. In 1878, using his share of the family fortune and the first money he had earned for himself, he was able to buy what was then a very modest weaving mill in Ober-Rosenthal bei Reichenberg in northern Bohemia (present-day Liberec). The mill lay in a region that was one of the country’s most important industrial centres, and known, not without reason, as the ‘Manchester of Bohemia’. Moriz Zweig’s investment in the latest mechanical looms from England quickly paid dividends, and the business grew in just a few years from a traditional manufactory to a thriving industrial enterprise. Despite his business commitments, Zweig continued to spend most of his time in Vienna, where in due course a branch outlet was established for the sale of the finished textiles. The mill in Bohemia was run by a company secretary, who enjoyed the complete confidence of his employer and remained with the company for many decades.

Despite his considerable successes, Moriz Zweig was cautious, not to say very cautious, in all his business and private affairs. This circumspection was not just a personal characteristic of his, but a general family trait common to all its male members. The family’s rapid rise, within a few generations, from the ghetto of a provincial town in Moravia to ownership of one of the country’s most successful weaving mills was highly gratifying to all those involved, but success did not breed excess, and the family was never given to vulgar ostentation or display. Moriz Zweig was very proud of the fact that he never had to sign a promissory note, that even in times of financial difficulty he never had to take out a loan, and that his account always remained in credit. It need hardly be said that he banked with the most respected banking houses of his day. Backward-looking though his attitude to money may have seemed in later years, when investing in other companies and speculating on the stock market had become second nature to the modern businessman, it looked like the future in his own day: for whatever opportunities and enticements the business world offered, the absolute first priority was to safeguard the family’s fortune and social status, which was dependent not least on the value and stability of its capital assets. It was important to have something to fall back on. The conditions for leading a “quiet” life in this sense were favourable, as long as one was comfortably off.

As a young man Moriz Zweig witnessed for himself the growth and expansion of modern Vienna. The railway network had long since been

extended to connect the capital with the Crown Lands, which had further stimulated economic growth. Extensive residential areas had been built in the industrial centres to house the immigrant workers, and the construction of public and private buildings on Vienna’s Ringstrasse was seen as a further monument in stone to the expansionist boom years of the

Gründerzeit

. After the initial euphoria this ambitious project was hit by a number of setbacks: the stock market collapse of 1873 briefly shook the business world to its foundations, and a number of entrepreneurs were plunged into ruin by the financial crisis. But the Zweig family appears not to have suffered any significant losses.

Moriz Zweig’s retiring ways were manifested not only in his business dealings, but also in his private life. He never played a prominent role in professional or business associations or on the city’s social circuit. He never accepted any award, and instead of cutting a figure at smart receptions he preferred to stay at home in the evenings and play on his beloved piano. The diary entry made by his son Stefan many years later, in December 1915, shows very clearly where this diffidence finally led him: “Father’s seventieth birthday. A very quiet affair, no emotion, no fuss or finery. One felt how cut-off we are from our world. Perhaps that’s how I will end up too. People can be a disappointment. Sometimes I understand the old man, even though I don’t want to become like him.”

3

In August 1878 Moriz Zweig announced his engagement. His future wife, Ida Brettauer, was nine years his junior and “a good match”, as the saying went, who was in line to receive a not insubstantial dowry. Like Moriz, she was not a native of Vienna, but had moved to the city from Italy when she was sixteen. Her father, Samuel Ludwig Brettauer, worked in banking and finance, and had settled with his family in Ancona, on Italy’s Adriatic coast, prior to Ida’s birth on 5th May 1854. Brettauer’s wife Josefine, a Landauer by birth, came from Hürben in the vicinity of Augsburg, while he himself hailed from Hohenems in Vorarlberg. Hence the fact that German was spoken at home among the immediate family while Ida was growing up, even though they were living in Italy. In addition to the languages of their native and adoptive countries, all the members of the family also spoke French. Multilingualism and a cosmopolitan approach to life came naturally to the Brettauers anyway. The wider family, with its lawyers, bankers and merchants, was scattered across many countries in Europe and as far afield as America. In good times it numbered presidents, aristocratic houses and even the Vatican

among its clients. The substantial successes that the family chalked up to its account—in the most literal sense—engendered a self-confidence and poise that could easily be interpreted by outsiders as snobbish conceit. In this respect Ida Brettauer ran true to type, and she changed little after her marriage to Moriz Zweig. As his later daughter-in-law Friderike put it, Moriz played the part of a retiring and conciliatory “prince consort” in the marriage—her point being that Ida Zweig was unquestionably cast in the role of queen.