Tides of Light (10 page)

Authors: Gregory Benford

“I’m on my way,” Killeen said, getting up. Having to end a meal this way irritated him and he added, “You should sharpen your

descriptive powers.” The phrase had the right edge of old-style Cap’nly speech, and he felt a certain pleasure in that.

—Sorry, Cap’n.—Cermo’s small voice was chagrined.—What it is…well, there’s some

ring

around the planet. And it’s gettin’ brighter.—

Killeen felt a cold apprehension. “It’s in orbit?”

—Nossir. Looks like it’s…it’s cuttin’ through.—

“Through what?”

—Through the whole damn planet, sir.—

At first Killeen did not believe that the image on the large screen could be real.

“You check for malfs?” he asked Cermo.

“Aye-aye, sir. I tried….” The big man’s forehead wrinkled. Cermo labored hard, but to him the complexity of the command boards

was a treacherous maze. Shibo gently took over from him, her hands moving with rippling speed over the touch-actuated command

pads.

After a long moment she said, “Everything checks. That thing’s real.”

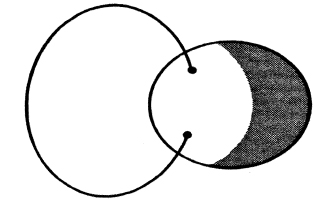

Killeen did not want to believe in the glowing circle that passed in a great arc through free space and then buried a third

of its circumference in the planet. Without understanding it he knew immediately that this was techwork on a scale he could

never have imagined. If mechs did this here, they had blundered into a place of danger beyond his darkest fears.

“Magnify,” he ordered curtly. He knew he had to treat this without showing alarm.

The hoop was three times larger than New Bishop. Its brilliant golden glow dimmed even the crisp glare of Abraham’s Star.

As the image swelled, Killeen expected to see detail emerge. But as the rim of New Bishop grew and flattened on the screen,

the golden ring was no thicker than before, a hard scintillant line scratched across space.

Except where it struck the planet’s surface. There a swirl of fitful radiance simmered. Killeen saw immediately that the sharp

edges of the ring were cutting into the planet. New Bishop’s thin blanket of air roiled and rushed about the ring’s sharp

edge.

“Max mag,” he said tensely. “Hold on the foot, where it’s touching.”

No, not touching, he saw. Cutting.

The bluehot flashes that erupted at the footpoint spoke of vast catastrophe. Clouds of pitted brown boiled up. Tornadoes churned

near each foot—thick rotating disks, rimmed by bruised clouds. At the vortex, violence sputtered in angry red jets.

Yet even at this magnification the golden hoop was still a precise, scintillating line. On this scale it seemed absolutely

straight, the only rigid geometry in a maelstrom of dark storms and rushing energies.

Toby and Besen and Loren had followed them to the command vault and now stood against the wall. He felt their presence at

his back.

“It’s moving,” Besen whispered, awed.

Killeen could barely make out the festering footpoint as it carved its way through a towering mountain range. Its knife-edge

brilliance met a cliff of stone and seemed to simply slip through it. Puffs of gray smoke broke all along the cut. Winds sheared

the smoke into strands. Then the hoop was slicing through the peak of a high snow-topped mountain, not slowing at all.

He peered carefully through the storm. Actual devastation was slight; the constant cloudy agitation and winds gave the impression

of fevered movement, but the cause of it all proceeded forward with serene indifference to obstacles.

“Back off,” he said.

Shibo made the screen pull away from the impossibly sharp line. The hoop pressed steadily in toward the center of New Bishop.

No longer a perfect circle, it steadily flattened on the side that pushed inward.

“Lined up with pole,” Shibo said. “Watch—I’ll project it.”

A graphic display appeared alongside the real image.

Cleaned of clouds, the planet’s image shone brightly. The hoop’s flat side was parallel to the axis of New Bishop’s rotation.

“Not natural,” Cermo said.

Killeen smothered the impulse to cackle with manic laughter.

Not natural! Why, whatever makes you say that, Lieutenant Cermo?

Yet in a way his instincts warred with his intelligence. The hoop shared a planet’s smooth curves, its size, its immense uncaring

grace. Killeen struggled to conceive of it as something made by design. This was tech beyond imagining. Mechs, he knew, could

carve and shape whole mountain ranges into their strange, crackling cities—but this…

“It’s moving toward the poles,” Shibo said, her voice a smooth lake that showed no ripples.

The hoop glowed brighter and flattened more and more as its inner edge approached the center of New Bishop. Killeen felt suspended,

all his hopes and designs dashed to oblivion by this immense simple thing that sailed so blithely through a planet.

“Where…where’d it come from?”

Cermo bit his lip in frustration. “From nowhere, Cap’n, I swear. When I saw it first it was dim, just barely there.”

“

Where?

”

“It was startin’ in on cuttin’ the air. Musta come from further out and just ran smack into New Bishop.”

Killeen did not believe this for a moment. He scowled.

Shibo said, “It lit up on impact?”

Cermo nodded. “I’d seen it before if it was bright.”

“So it’s drawing its light from what it’s doing to the planet,” she deduced, her eyes distant. “That’s why we didn’t see it

before.”

Killeen wondered momentarily how she could remain so abstract while confronting events so huge. His own imagination was numbed.

He struggled to retain some grip on events by digressing into detail. “How…how thick is it?”

Shibo’s glance told him that she had noticed the same strange sharpness. “Smaller than the

Argo

, I’d judge,” she said, her eyes narrowing.

“That small,” Cermo said distantly, “but it’s cutting through all that.”

Shibo said, “Planet does not split.”

Cermo nodded. “It’s holdin’ together. Some places you can see where the thing’s cut through rock and left a scar. But the

rock closes up behind it.”

“Pressure seals scar again,” Shibo agreed.

“It’s no kind knife I ever saw,” Killeen said, and instantly regretted making such an empty statement. In the face of a thing

like this, the crew had to believe their Cap’n wasn’t as dazed as they were. Doubtless, many had already seen the golden hoop

from other parts of the ship. It might throw them into blind panic. Killeen’s own impulse had been to get away from the thing

as fast as possible. That might, indeed, be the smart thing to do. But they had come so far….

Toby asked, “D’you think…maybe it’s not like a knife at all. Could be some thing lives off planets? Eats ’em?”

The idea was both absurd and also not dismissable, Killeen thought. Reasonableness was no guide here.

“If it eats all that rock, howcome it’s so thin?” he said with elaborate casualness. Besen laughed merrily and somehow the

meaningless joke relaxed the small party.

“Why would mechs make it, then?” Toby persisted.

Killeen noted ruefully that no one considered for a moment the possibility that humans might have ’factured such a thing.

The glittering, jewellike Chandeliers had been the peak of human endeavor, ages ago. The numbing simplicity of this glowing

ring immediately spoke of an alien mind at work here, acting through majestic perspectives.

The mute indifference of this glowing thing was the final judgment against them all, Killeen thought. Their endless ruminations

and longings had invested their destination with such weight, and now this silent slicing of their freshly named world ended

all speculation. Fragile humanity could not live on such a vast canvas, the plaything of forces beyond fathoming. Their quest

had ended in disaster even before they could set foot on the soil of their new paradise.

“Hey, maybe

Argo

can do somethin’ ’bout that thing,” Toby said eagerly.

Loren joined in. “Yeasay, ask the systems if they can cook somethin’ for that.”

Killeen had to smile, though he did not take his eyes from the screen. A sixteen-year-old boy knew no constraints, could imagine

no problem that he could not meet with the right measure of savvy and sheer boundless bursting energy. And who was he to say

no?

“Try,” he said to Shibo, gesturing with one hand.

She worked over the control pads for long moments, lines creasing her face in concentration. Finally she slapped

the console and shook her head. “No memory.

Argo

doesn’t recognize this thing.”

Killeen summoned up all his Aspects. They were happy for even momentary attention but only one had any useful idea. This was

Grey, a woman from the High Arcology Era. She was a somewhat truncated personality, suffering from sentence-constructing disability

because of a transcription error a century before. She knew scientific and historical lore of her own and earlier times. Her

voice was halting and cluttered with purring static, heavily accented with the dust of time.

I believe it…is what was called by theoreticians…a “cosmic string.” They were known…in Chandelier Age…but only theory…hypothetical

objects…I studied…these matters in…youth…

“Looks real to me,” Killeen muttered to himself.

We believed…they were…made at the very earliest moments…of…universe. You can envision…at that time…a cooling, expanding mass.

It failed…to be perfectly symmetrical and uniform. Small fluctuations produced…defects in the vacuum state…states of certain

elementary particles

—

What the hell’s that mean?

Killeen thought irritably. He was watching the hoop slowly cut through a slate-gray plain. Around him the control vault had

fallen into numbed silence. His Arthur Aspect broke in:

I believe matters could proceed better if I translated from Grey for you. She is having difficulty

.

Killeen caught the waspish, haughty air the Aspect sometimes took on when it had been consulted too infrequently for its own

tastes. He remembered his father saying to him once, “

Aspects smell better if you give ’em some air

” and resolved to let them tap into his own visual and other sensory web more often, to stave off cabin fever. He murmured

a subvocal phrase to entice the Aspect to go on.

Think of ice freezing on the surface of a pond. As it forms there is not quite enough area, perhaps, and so small crinkles

and overlaps appear. These ridges of denser ice mark the boundary between regions which did manage to freeze out smoothly.

All the errors, so to speak, are squeezed into a small perimeter. So it was with the early universe. These exotic relics are

compacted folds in space, tangles of topology. They have mass, but they are held together primarily by tension. They are like

cables woven of warped space-time itself.

“So what?”

Well, they are extraordinary objects, worthy of awe in their own right. Along their lengths, Grey tells me, there is no impediment

to motion. This makes them superconductors!—so they respond strongly to magnetic fields. As well, if they are curved—like

this one—they exert tidal forces on matter around them. Only over a short range, however—a few meters. I should imagine that

this tidal stretching allows it to exert pressures against solid material and cut through it.

“Like a knife?”

Indeed—the best knife is the sharpest, and cosmic strings are thinner than a single atom. They can slide between molecular

bonds.

“So it just slides right through everything,” Killeen mused to himself.

Yes, but, well—think of what we witness here! A flaw in the continuity of the very laws that govern matter. Nature allows

such transgressions small room, and the discontinuity derives a tension from its own wedged-in nature—a stress that communicates

along its stretched axis. And so we can see this incomparably slim marvel, because it is bigger than a planet along its length.

“So why’s this one cutting through New Bishop? It just fall in by accident?”

I sincerely doubt that such a valuable object would be simply wandering around. Certainly not at Galactic Center, where entities

are sophisticated enough to understand their uses.

“Somebody’s usin’ it? For what?”

That I do not know.

Grey’s wispy tones sifted over Arthur’s:

I heard of astronomers…observed distant strings…but no record…of use. Were born…as relativistic objects…but slowed down…through

collisions

with…galaxies…finally came to rest…here…at Center…

When her voice faded Arthur said:

I would imagine handling such a mass is a severe technical difficulty. Since it is a perfect superconductor, holding it in

a magnetic grip suggests itself. The sure proof of my view, then, would be fluctuating magnetic fields in the region near

the outer part of the hoop.

Killeen recognized Arthur’s usual pattern—explain, predict, then pretend haughty withdrawal until Killeen or somebody else

could check the Aspect’s prediction. He shrugged. The idea sounded crazy, but it was worth following up.