Time Travel: A History (31 page)

Read Time Travel: A History Online

Authors: James Gleick

Tags: #Literary Criticism, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science, #History, #Time

*11

“That there is a place for the present moment in physics becomes obvious when I take my experience of it as the reality it clearly is to me and recognize that space-time is an abstraction that I construct to organize such experiences,” says David Mermin.

THIRTEEN

Our Only Boat

Story is our only boat for sailing on the river of time.

—Ursula K. Le Guin (1994)

YOUR NOW IS

not my now. You’re reading a book. I’m writing a book. You’re in my future, yet I know what comes next—some of it—and you don’t.

*1

Then again, you can be a time traveler in your own book. If you’re impatient, you can skip ahead to the ending. When memory fails you, just turn back the page. It’s all there in writing. You’re well acquainted with time traveling by page turning, and so, for that matter, are the characters in your books. “I don’t know how to put it exactly,” says Aomame in Haruki Murakami’s

1Q84,

“but there is a sense of time wavering irregularly when you try to forge ahead. If what is in front is behind, and what is behind is in front, it doesn’t really matter, does it?” Soon she appears to be changing her own reality—but you, the reader, can’t change history, nor can you change the future. What will be, will be. You are outside it all. You are outside of time.

If this seems a bit meta, it is. In the era of time travel rampant, storytelling has gotten more complicated.

Literature creates its own time. It mimics time. Until the twentieth century, it did that mainly in a sensible, straightforward, linear way. The stories in books usually began at the beginning and ended at the end. A day might pass or many years but usually in order. Time was mostly invisible. Occasionally, though, time came to the foreground. From the beginning of storytelling, there have been stories told inside other stories, and these shift time as well as place: flashbacks and flash-forwards. So aware are we of storytelling that sometimes a character in a story will

feel

like a character in a story, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, at time’s mercy:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow…

Or perhaps we here in real life develop a nagging suspicion that we are mere characters in someone else’s virtual reality. Players performing a script. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern imagine they are masters of their fate, and who are we to know better? The omniscient narrator of Michael Frayn’s 2012 novel

Skios

says of the characters living in his story, “If they had been living in a story, they might have guessed that someone somewhere had the rest of the book in his hands, and that what was just about to happen was already there in the printed pages, fixed, unalterable, solidly existent. Not that it would have helped

them

very much, because no one in a story ever knows they are.”

In a story one thing comes after another. That is its defining feature. The story is a recital of events. We want to know what happens next. We keep listening, we keep reading, and with any luck the king lets Scheherazade live for one night more. At least this was the traditional view of narrative: “Events arranged in their time sequence,” as E. M. Forster said in 1927—“dinner coming after breakfast, Tuesday after Monday, decay after death, and so on.” In real life we enjoy a freedom that the storyteller lacks. We lose track of time, we drift and dream. Our past memories pile up, or spontaneously intrude on our thoughts, our expectations for the future float free, but neither memories nor hopes organize themselves into a timeline. “It is always possible for you or me in daily life to deny that time exists and act accordingly even if we become unintelligible and are sent by our fellow citizens to what they choose to call a lunatic asylum,” said Forster. “But it is never possible for a novelist to deny time inside the fabric of his novel.” In life we may hear the ticking clock or we may not; “whereas in a novel,” he said, “there is always a clock.”

Not anymore. We have evolved a more advanced time sense—freer and more complex. In a novel there may be multiple clocks, or no clocks, conflicting clocks and unreliable clocks, clocks running backward and clocks spinning aimlessly. “The dimension of time has been shattered,” wrote Italo Calvino in 1979; “we cannot love or think except in fragments of time each of which goes off along its own trajectory and immediately disappears. We can rediscover the continuity of time only in the novels of that period when time no longer seemed stopped and did not yet seem to have exploded, a period that lasted no more than a hundred years.” He doesn’t say exactly when the hundred years ended.

Forster might have known he was oversimplifying, with modernist movements rising self-consciously all around. He had read Emily Brontë, who rebelled against chronological time in

Wuthering Heights.

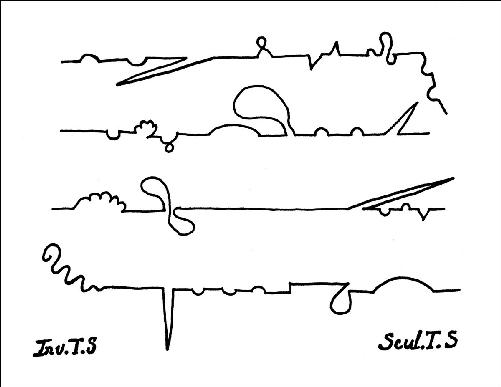

He had read Laurence Sterne, whose Tristram Shandy had “a hundred difficulties which I have promised to clear up, and a thousand distresses and domestic misadventures crowding in upon me thick and threefold” and threw off the shackles of tense—“A cow broke in (tomorrow morning) to my uncle Toby’s fortifications”—and even diagrammed his temporal divagation with a timeline of squiggles, back and forth, up and around.

Forster had read Proust, too. But I’m not sure he had gotten the message: that time was busting out all over.

It had seemed that space was our natural dimension: the one we move about in, the one we sense directly. To Proust we became denizens of the time dimension: “I would describe men, even at the risk of giving them the appearance of monstrous beings, as occupying in Time a much greater place than that so sparingly conceded to them in Space, a place indeed extended beyond measure…like giants plunged in the years, they touch at once those periods of their lives—separated by so many days—so far apart in Time.”

*2

Marcel Proust and H. G. Wells were contemporaries, and while Wells invented time travel by machine, Proust invented a kind of time travel without one. We might call it mental time travel—and meanwhile psychologists have appropriated that term for purposes of their own.

Robert Heinlein’s time traveler, Bob Wilson, revisits his past selves—conversing with them and modifying his own life story—and in his way the narrator of

In Search of Lost Time,

sometimes named Marcel, does that, too. Proust, or Marcel, has a suspicion about his existence, perhaps a suspicion of mortality: “that I was not situated somewhere outside of Time, but was subject to its laws, just like the people in novels who, for that reason, used to depress me when I read of their lives, down at Combray, in the fastness of my wicker chair.”

“Proust upsets the whole logic of narrative representation,” says Gérard Genette, one of the literary theorists who attempted to cope by creating a whole new field of study called narratology. A Russian critic and semioticist, Mikhail Bakhtin, devised the concept of “chronotope” (“time-space,” openly borrowed from Einsteinian spacetime) in the 1930s to express the inseparability of the two in literature: the mutual influence they exert upon each other. “Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible,” he wrote; “likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history.” The difference is that spacetime is just what it is, whereas chronotopes admit as many possibilities as our imaginations allow. One universe may be fatalistic, another may be free. In one, time is linear; in the next, time is a circle, with all our failures, all our discoveries doomed to be repeated. In one, a man retains his youthful beauty while his picture ages in the attic; in the next, our hero grows backward from senescence to infancy. One story may be ruled by machine time, the next by psychological time. Which time is true? All, or none?

Borges reminds us that Schopenhauer asserted that life and dreams are pages from the same book. To read them in their proper order is to live, but to browse among them is to dream.

The twentieth century gave storytelling a roisterous temporal complexity like nothing that had been seen before. We don’t have enough tenses. Or rather, we don’t have names for all the tenses we create.

*3

“In what was to have been the future”—that simple clause is the opening of Madeleine Thien’s novel

Certainty.

Proust lines a temporal path with mirrors:

Sometimes passing in front of the hotel he remembered the rainy days when he used to bring his nursemaid that far, on a pilgrimage. But he remembered them without the melancholy that he then thought he would surely some day savor on feeling that he no longer loved her. For this melancholy, projected in anticipation prior to the indifference that lay ahead, came from his love. And this love existed no more.

Memories of anticipation, anticipation of memories. To make sense of the time loops narratologists draw symbolic diagrams. We may leave the details to the technicians and savor the new possibilities.

Mixing memory and desire.

The point is that for novelists as much as for physicists the timescape began to replace the landscape. The church of Marcel’s childhood is, for him, “an edifice occupying a space with, so to speak, four dimensions—the fourth being Time—extending over the centuries its nave which, from bay to bay, from chapel to chapel, seemed to vanquish and penetrate not only a few yards but epoch after epoch from which it emerged victorious.” The other great modernists—especially Joyce and Woolf—likewise made time their canvas and their subject. For all of them, Phyllis Rose has observed, “the prose line wandered in time and space, with any moment in the present acting as a kind of diving platform offering access to a lake of memory, anticipation, and association.” Storytelling is unchronological. It is anachronistic. If you are Proust, the narrative of life blends into the life: “life being so unchronological, so anachronistic in its disordering of our days.” The narrative itself is the time machine, and memory is the fuel.

Like H. G. Wells, Proust absorbed the new geology. He digs in his own buried strata: “All these memories added to one another now formed a single mass, but one could still distinguish between them—between the oldest, and those that were more recent, born of a fragrance, and then those that were only memories belonging to another person from whom I had learned them—if not fissures, if not true faults, at least that veining, that variegation of coloring, which in certain rocks, in certain marbles, reveal differences in origin, in age, in ‘formation.’ ” We might criticize Proust’s view of memory as merely poetic if our modern neuroscientists had settled on a more authoritative model of how memory works, but they have not. Even with the example of computer storage to draw on, even with our detailed neuroanatomies of the hippocampus and the amygdala, no one can really explain how memories are formed and retrieved. Nor can anyone explain away Proust’s paradoxical contention: that the past cannot truly be recovered by searching our memories, by interrogating them, by rewinding the film or reaching back into the drawer; rather, that the essence of the past, when it comes to us at all, comes unbidden.

He invented the term “involuntary memory” for this. He warned: “It is a waste of effort for us to try to summon it, all the exertions of our intelligence are useless. The past is hidden outside the realm of our intelligence and beyond its reach.” We may think, peering naïvely into our minds, that we have formed our memories and may now call them up for leisurely inspection, but no, the memory we reach for, the memory of the conscious will, is an illusion. “The information it gives about the past preserves nothing of the past itself.” Our intelligence rewrites and rewrites again the story it is trying to recall. “The mind feels overtaken by itself; when it, the seeker, is also the obscure country where it must seek.” Involuntary memory is the grail for which we may not quest. We don’t find it; it finds us. It may lie hidden perchance in a material object—“in the sensation that this material object would give us”—for example, oh, the taste of a

petite madeleine

dipped in lime-blossom tea. It may come in the liminal space between waking and sleep. “Then the confusion among the disordered worlds will be complete, the magic armchair will send him traveling at top speed through time and space.”

All things considered, it may seem surprising that it took psychologists sixty more years to define this phenomenon and give it the name “mental time travel,” but they have done that now. A neuroscientist in Canada, Endel Tulving, coined the term for what he called “episodic memory” in the 1970s and 1980s. “Remembering, for the rememberer, is mental time travel,” he wrote, “a sort of reliving of something that happened in the past.” Or the future, naturally. (It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backward, remember.) It’s MTT, for short, and researchers debate whether it is a uniquely human capability or whether monkeys and birds may also revisit their pasts and project themselves into the future. A more recent definition by two cognitive scientists: “Mental time travel is the ability to mentally project oneself backward in time to relive past experiences and forward in time to pre-live possible future experiences. Previous work has focused on MTT in its voluntary form. Here, we introduce the notion of involuntary MTT.” In other words, “involuntary (spontaneous) mental time travel into the past and future.” No mention of madeleines, though.