Read Time Travel: A History Online

Authors: James Gleick

Tags: #Literary Criticism, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science, #History, #Time

Time Travel: A History (34 page)

SALLY:

How can you have a copy of the finished transcript? It’s still being written.

THE DOCTOR:

I told you. I’m a time traveler. I got it in the future.

SALLY:

Okay, let me get my head round this. You’re reading aloud from a transcript of a conversation you’re still having.

THE DOCTOR:

Yeah. Wibbly wobbly, timey wimey.

The TARDIS still needs to reunite with the Doctor. The Doctor still needs to get his hands on the transcript. Before the intricate machinery of this plot is complete, Sally, who now understands the whole story, will have to meet a version of the Doctor who has not yet grasped it. Now her past is his future. “Blink” is all the paradoxes rolled together with a Möbius twist. It’s Predestination and Free Will conversing in real time, via technology new for one and obsolete for the other.

By 2007 the internet was in full flow, but it plays no obvious part in the story. Cyberspace is an offstage presence—the dog that doesn’t bark in the night. This unusual episode of

Doctor Who

expressed something about our complexified relationship with time. Nowadays, Sally Sparrow’s in-box will be overflowing with thousands of emails, mingling past and present, which she may view threaded or flat, and the number only grows, and she is entirely capable of carrying on multiple conversation threads, SMS and MMS, emoji and video, simultaneous and asynchronous, with two participants or many, and meanwhile, with or without earbuds, she hears voices and glimpses screens everywhere, in waiting rooms and on signposts, and if she pauses to think, she may have trouble placing all the information in proper temporal sequence—wibbly wobbly, timey wimey—but who pauses to think?

—

WHEN THE BROTHERS

Louis and Auguste Lumière invented the

cinématographe

in the 1890s, they did not begin by filming actors dressed in costumes. They did not make fictional movies. They trained operators in the new technology and sent Clément and Constant and Félix and Gaston and many more across the globe to record snippets of real life. Naturally they filmed workers leaving their own factory—who could resist

La sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon

?—but by 1900 they were filming a cockfight in Guadalajara, and the foot traffic on Broadway, and men smoking opium in what is now Vietnam. Audiences flocked to see these scenes of faraway live action. The creation of these images marks an event horizon. When we look back, the pre-1900 past is less visible. It’s good we have books.

So much of the world comes to us on screens now, with sound as lifelike as the picture. The screens range farther than anyone could ever see unaided. Who is to say that these are not time gates? People “stream” music to us and video, the tennis match we’re watching may or may not be “live,” the people in the stadium watching the instant replay on the stadium screen, which we see repeated on our screen, may have done that yesterday, in a different time zone. Politicians record their responses to speeches they have not yet seen, for instant broadcast. If we confuse the real world with our many virtual worlds, it’s because so much of the real world is virtual. For many people, there is no personal memory of a time without screens. So many windows, so many clocks.

“Internet time” became a term of art. Andrew Grove, chief executive of Intel, 1996: “We are now living on internet time.” Often this was just a cool-kids way of saying “faster,” but our relationship to time was changing yet again, even if no one quite understood what or how. On internet time the past bleeds into the present. And the future? There seems to be a feeling that the future is already here. Blink and it has happened. Thus the future vanishes.

“Increasingly, our concepts of past, present and future are being forced to revise themselves,” wrote J. G. Ballard in 1995—science fiction, as ever, the canary in the coal mine. “The future is ceasing to exist, devoured by the all-voracious present. We have annexed the future into the present, as merely one of those manifold alternatives open to us.”

We are annexing the past as well. Institutions from

Scientific American

to

The Bridge World

spill open their archives to reveal what was new

50 Years Ago.

The online front page of the

New York Times

recycles its first reporting on bagels and pizza. Backward reels the global mind. Just when the obsession with newness seemed more ferocious than ever, Svetlana Boym, a time-twisting theorist of nostalgia, observed: “The first decade of the twenty-first century is not characterized by the search for newness, but by the proliferation of nostalgias that are often at odds with one another. Nostalgic cyberpunks and nostalgic hippies, nostalgic nationalists and nostalgic cosmopolitans, nostalgic environmentalists and nostalgic metrophiliacs (city lovers) exchange pixel fire in the blogosphere.” For all this blooming shape-shifting nostalgia we can thank the time travelers. “The object of romantic nostalgia must be beyond the present space of experience,” Boym writes, “somewhere in the twilight of the past or on the island of utopia where time has happily stopped, as on an antique clock.”

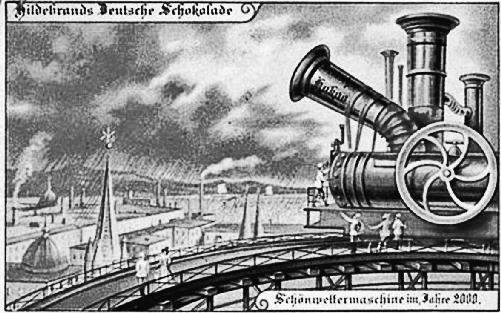

What a strange ending for the twentieth century! The new century—the new millennium, for those who were counting—arrived with televised fireworks and bands playing (and computer panic) but scarcely a glimmer of the glorious optimism that lit up the year 1900, when everyone seemed to be rushing to the prow of a great ship and gazing hopefully toward the horizon, dreaming of their scientific future: airships, moving sidewalks,

Schönwettermaschinen

, underwater croquet, flying cars, gas-powered cars, flying people.

Andiamo, amici!

Many of those dreams came true. So when the new millennium dawned, what bright dreams for the year 3000? Or the year 2100?

Newspapers and websites polled their readers for predictions. They were disappointing.

We will control the weather.

(Again.)

Deserts will become tropical forests.

Or the reverse.

Space elevators.

But not much space travel. Warp drive and wormholes notwithstanding, we seem to have given up on populating the galaxy.

Nanorobots. Remote-control warfare.

The internet in your contact lens or brain implant. Self-driving cars, a comedown, somehow, from

i futuristi

and their fearsome roaring racing machines. The aesthetic of futurism changed, too, without anyone issuing a manifesto—from big and bold, primary colors and metallic shine to grim, dank rot and ruins. Genetic engineering and/or species extinctions. Is that all the future we have to look forward to? Nanobots and self-driving cars?

Card produced c. 1900 by Hildebrands chocolate company

If we lack space travel, we do have telepresence. “Present” in this context pertains to space, not to time. Telepresence was born in the 1980s, when remotely controlled cameras and microphones came into their own. Deep sea explorers and bomb squads can project themselves elsewhere—project their souls, their eyes and ears, while the body remains behind. We send robots beyond the planets and inhabit them. In the same decade the word

virtual,

already by then a computer term, began to refer to remote simulations—virtual office, virtual town halls, virtual sex. And, of course, virtual reality. Another way to look at telepresence is that people virtualize themselves.

A women finds herself piloting a quadcopter in a slightly creepy “beta of some game”—like a first-person shooter with “nothing to shoot”—and because she is a character in a novel by William Gibson (

The Peripheral,

2014) we must already wonder what is virtual and what is real. Her name is Flynne and she seems to live somewhere in the American South—back country, trailer down by the creek. But in the present or the future? Hard to know exactly. At the very least, waves of the future are lapping at the shore. Marine vets have scars, physical and mental, from implanted “haptics.” The era’s namespace includes Cronut, Tesla, Roomba, Sushi Barn, and Hefty Mart. Roadside storefronts offer “fabbing”—three-dimensional printing of practically everything. Drones are ascendant. Every buzzing insect is a potential spy.

Anyway, Flynne leaves her reality behind to pilot her drone through a different, virtual reality. A mysterious (virtual?) corporate entity is paying her to do it. She hovers near a great dark building. She looks up—camera up. She looks down—camera down. “All around her were whispers, urgent as they were faint, like a cloud of invisible fairy police dispatchers.” Everyone knows how immersive a computer game can become, but what is her goal? Her purpose? Apparently she is meant to chase away other drones, which swarm like dragonflies, but it doesn’t feel like any game she has played before.

*4

Then—a window, a woman, a balcony—Flynne witnesses a murder.

We have met Gibson before: the futurist who denies writing about the future. It was Gibson who invented the word

cyberspace

in 1982 after watching kids playing video games at an arcade in Vancouver, staring into their consoles, turning knobs and pounding buttons to manipulate a universe no one else could see. “It seemed to me that what they wanted was to be inside the games, within the notional space of the machine,” he said later. “The real world had disappeared for them—it had completely lost its importance. They were in that notional space.” There was no such thing as cyberspace then—as Gibson imagined it, “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation.” The space behind all the computers. “Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data.” We all feel that way sometimes.

At some point it occurred to Gibson that he had been describing something like the “Aleph” of Borges’s 1945 story: a point in space that contains all other points. To see the Aleph you must lie flat and immobile in darkness. “A certain ocular adjustment will also be necessary.” What you see then cannot be contained in words, Borges writes,

for any listing of an endless series is doomed to be infinitesimal. In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful; not one of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency. What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write down will be successive, because language is successive.

The

space

in cyberspace vanishes. It collapses into a network of connections: as Lee Smolin said, a billion-dimensional space. Interaction is all. And what of cybertime? Every hyperlink is a time gate.

*5

Millions of acts both delightful and awful—posts, tweets, comments, emails, “likes,” swipes, winks—appear simultaneously or successively. Signal speed is light speed, time zones overlap, and time stamps shift like motes in a sunbeam. The virtual world is build on transtemporality.

Gibson, who always felt time travel to be an implausible magic, avoided it through ten novels written across thirty years.

*6

Indeed, as his imagined futures kept crowding in on the conveyor belt of the present, he renounced the future altogether. “Fully imagined futures were the luxury of another day, one in which ‘now’ was of some greater duration,” says Hubertus Bigend in the 2003

Pattern Recognition.

“We have no future because our present is too volatile.” The future stands upon the present, and the present is quicksand.

Back to the future once more, though, in Gibson’s eleventh novel,

The Peripheral.

A near future interacts with a far future. Cyberspace gave him a way in. New rules of time travel: matter cannot escape its time but information can. The future discovers that it can

email

the past. Then it

phones

the past. The information flows both ways. Instructions are sent for 3-D fabbing: helmets, goggles, joysticks. It is a marriage of time shifting and telepresence.

To the people of the future, the denizens of the past can be employed as “polts” (from

poltergeist

—“ghosts that move things, I suppose”). Money can be sent or created (win lotteries, manipulate the stock market). Finance has become virtual, after all. Corporations are shells, built of documents and bank accounts. It’s outsourcing in a new dimension. Does the manipulation of people across time create headaches? “Far less than the sort of paradox we’re accustomed to culturally, in discussing imaginary transtemporal affairs. It’s actually quite simple.” After all, we know about time forks. We are aficionados of branching universes. “The act of connection produces a fork in causality, the new branch causally unique. A stub, as we call them.”

Not that paradoxes are unknown. At one point a future law-enforcement agent called Detective Inspector Ainsley Lowbeer explains to an avatar—exoskeleton, homunculus,

peripheral

—inhabited by Flynne, “I’m told that arranging your death would in no way constitute a crime here, as you are, according to current best legal opinion, not considered to be real.” Nanobots are real. Cosplay is real. Drones are real. Futurity is done.