Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (8 page)

Read Tori Amos: Piece by Piece Online

Authors: Tori Amos,Ann Powers

ANN:

Amos's teachers came from everywhere: from within her family, from the radio, from the land itself. But Amos also famously gained a formal musical education. The years she spent studying at the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore taught her both discipline and disappointment. She had other teachers as well: in piano practice rooms, and in the lounges she began playing in as a teen. And one teacher, her father, remained central.

I'd been dreaming through the night one night last fall, just kind of going back in time, and I woke up to a message: Husband said, “Somebody called yesterday.” I was getting the tea ready that morning, getting Tash ready, and he just looked and said, “Now is not a good time to tell you this, but it came in yesterday and I didn't tell you then 'cause that wasn't a good time, either.” He said, “Somebody called and your music teacher died.” I said, “Which one?” And he wrote down the name and he showed me, and it was Diana Morrison, who was a voice teacher of mine when I was about eighteen, until I was twenty-one. She came to my shows up until a few years ago when she got a bit older, but she was one of those really vibrant creatures.

Colorful scarves, blond curly hair, older, though. From an earlier generation, but a feminist and a real force in music in the Washington, D.C., area. And very, very much a part of my music. She trained people for years, showing them how to not destroy their voices. I had gotten nodes like any other singer; I mean, I was singing six nights a week, five or six hours a night in the days when she was my coach. Knowing that she died put me in this place of going back. I've had so many teachers for different things, and it's important to acknowledge that.

Though I heard my brother's and my mother's records, in a formal sense I was exposed to classical music before pop. People always toss around the phrase

child prodigy

to refer to my years at the Peabody Conservatory, because I was so young, five, when I started there. It was assumed—by my parents, my teachers, and myself at that time—that I would go on to become a concert pianist. That's what you do if you're in a place like that—you're not just playing, you're there to be a champion. No different from a gymnast studying with Bela Karolyi: at a certain point you're daft to do it if you aren't going to win, and if you don't cut the mustard you become a teacher or just leave.

I had trouble reading music. My ear was good. I could hear and play things back, but I struggled with reading. When I say that, I mean I could read better than most people, I could read Debussy and Bartók, but not Chopin. At eight years old, I wasn't playing

Fantasie Impromptu

, and that was a bit young, but I should have been playing it, and other pieces on this level, soon.

I knew that I couldn't compete with the best in the world, and the clocks were ticking. Three years previous I'd been untouchable for my age, and then suddenly I wasn't. I sought out people at the conservatory who would be straight with me, other students, and I knew I was marked, just as I'd been marked by my grandmother at home. I knew I was a disappointment,

and it was sad to not be the Girl Wonder anymore. My father, particularly couldn't accept it. And in a strange way it's a good thing that he didn't, because he never gave up on me. But I started to spend time with the composers at school and began to see that this was a very different endeavor. I was very humbled by the tradition of composing, but I also knew that, as a composer, I didn't have to achieve an apex when I was eleven.

I started to let people know that I loved this other kind of music. I think I was ten when I said to one of my teachers, “What about the idea of John Lennon? Lennon and McCartney as modern-day Mozarts.” That was just blasphemous. There wasn't a place for the idea of being a contemporary composer, working in the pop idiom. Jazz was acceptable; in fact, it's a big piece of the Peabody program. And now I think they actually do have a contemporary music program—they've asked me to come and lecture, which is so funny. I don't know if I'll do it, or if I would be good at doing it. Maybe it's better for me to just teach by example.

By the time I left the Peabody, I was really listening to contemporary music. It was my life, my blood. I was composing a lot. At the insistence of my father I did continue to take lessons, under a Roman Catholic nun at St. Camilla's, a school close by. Her name was Sister Ernestine. I did it for my dad. She snoozed through our lesson usually, so I just composed instead of playing Rachmaninoff, although I love the Russians. I had romances with these composers in my head. Through the music I joined with them, coupling with their motifs in my left hand. I actually kept taking lessons on and off until I was twenty, because that's just what I did.

When I was around twelve I began to share the songs I was writing with my girlfriends. I even won the Montgomery County Teen Talent Competition with one of my own songs. I beat out a girl who was fourteen who went to my school. Wendy Nelson. She was just the coolest thing. She

would talk about this guy called Bruce Springsteen and sing all of his songs at the piano. Later, when people would say, “You must have been inspired by Kate Bush as a teen,” I'd say honestly I'd never even heard of her back then. Wendy Nelson was my inspiration.

At fourteen I started performing on the lounge circuit and learning my repertoire. That was my father's idea, and though it may forever seem strange that a minister sent his teenage daughter into gay clubs to sing and play, thank God he did. There was nowhere else that would accept me as a performer. The gay community embraced me just as I was working through my own sexuality and gave me a safe place to deal with that. One night someone came up to my father when I was playing at a bar called Mr. Henry's, and said, “How in the world can you bring your daughter into a gay club?” And he replied, “Well, she won't be going home with any of you!” He had the situation sussed out. He knew I needed to learn my trade and I could do it there. Sometimes the Great Mother visits us in unexpected ways. I remember the gay waiters, specifically one called Joey; he showed me how to dress, how to push a Joan Fontaine look, and how to give a blow job on a cucumber, swathed in cashmere, of course—this way he could always check for teeth marks.

As with every school I attended, I eventually had to leave the lounges. A friend of mine in D.C., Steve Himmelfarb, convinced me. Steve's dad was living in North Hollywood, and he moved out there to become a recording engineer. Then he came back to see me. One night we were having a coffee after I'd been playing in downtown D.C. and he said, “You're going to have to get out of here at a certain point. What is it going to take? You will be doing this at thirty, playing for these senators. They're going to give you a dollar in your tip jar, and you're going to get old. That's it.” He could see the future. Soon after Steve's speech, I moved to L.A. He became an engineer at Capitol, and you know what happened to me.

At that point I had to leave the person dearest to me, my mother. I had to leave my father, my greatest teacher, behind. When you are twenty-one and making as much money as your father—ministers and teachers don't make much money (not that that's right, but that is “what it is)—the curfews and the disagreements over whom I should date and how I should behave all got to be too much. He and I get along much better now, but at that time it was really overbearing, and I knew that I had to become a woman.

ANN:

Corn Mother's story brings to light the importance of honoring your origins, but it also makes room for humans to seize their own destiny. The earth goddess's grandsons create civilization with the hunt, and though they no longer live in an Eden, they inhabit the real world. An artist must also go beyond her origins to fully realize her vision. For Amos, this moment of separation began when she named herself.

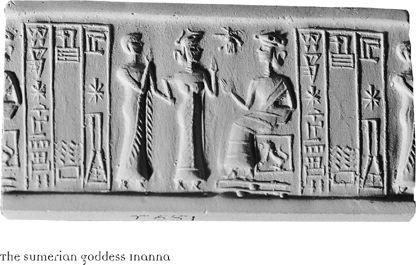

The Sumerian goddess Inanna

People called me Ellen, my middle name, during most of the years of my apprenticeship. I was fifteen when I realized I needed my own name, but for a while I didn't know what it was. I went through tons of names, even Sammy Jay; there were a lot of different ideas floating through—I don't know if you can actually call them ideas, more like brain farts. Finally, when I was seventeen, somebody just walked in one night and revealed it to me. It wasn't someone close to me—just a guy my friend Linda McBride dated for a couple of weeks. They came into one of the lounges where I played, just to have a drink, and when she introduced him to me, he said, “You're a Tori.”

And I just kind of went,

I think you re right.

Soon after that, a friend of mine who worked in the Reagan administration came to the piano bar. I told him my new name, and he said, “You can't be a Tory. I mean, it's like calling yourself a Republican, only British.” And I said, “I don't care. I just don't care.” I knew the spelling wouldn't be like that anyway.

When I consider why I took that name for myself, I realize that maybe I was trying to create another potential. Myra was my given name; the root of Myra is, of course, Mary. And I understand that I carry that. It was important to my father that all the women in his life, my sister and my mother and I, had forms of Mary. He was devoted to the mother Mary. There's a respect there, for Jesus’ mother. The Magdalene, however, they didn't even call her Mary—she wasn't a consideration.

So in our family there was Mary Ellen, my mother, Marie Allen, my sister, and I was Myra Ellen. So I really felt I could not create my own destiny—it's almost as if I was given cement and told to build a cabin. I knew that certain controls were in place that I couldn't break. I could not break through the opinions of who Myra Ellen was and what was expected of her.

Again, we go back to the power of words and how they can make you feel. They bring liberation or stagnation, they're chains. I began to see the structure of Tori—there's conserva

tory

, and

victory:

you see that word in so many different other words—also anti-inflammatory but my favorite has to be Yakatori chicken. And I began to feel that the sound of this name was a window. Although I can't fly, it gave me access to go to certain subjects, to get into secret ideologies. To travel, which I've been doing ever since.

There were two Jamaican nurses taking care of me. They were both deeply religious women. They believed in God and followed the Bible word for word. I would speak to them of the Great Mother; I would tell them that they reminded me of the depth of love that I felt from the Great Mother. When I would sit by the sea, so as to let the rushing of the winds and the salt clear the way—cleansing the thoughts that were pulling me down, I would reach for the hands of these two women. All three of us believed that there were forces that could pull you down. Pull you away from your center. They called it Satan. I didn't choose to disagree with that terminology. Satan means different things to different people, and a lot of people see it as an outside force working to recruit people into his army. Over the years I've chosen to see it somewhat differently. I believe that this force, called Satan, if you will, is a position from which you or I choose to act. This force takes no responsibility for the suffering it causes. Some people who need to have power over other people can't see that they are operating within the satanic framework. If you stop walking on eggshells and are honest about it—dominating another human being, needing to control another human being,

even if it's in that person's best interest, treating someone like a possession, taking advantage of another human being because you can—all of this is what 666 really is. The misuse of power. Not all of us are willing to admit where we're misusing our power.

I would sit and speak for hours and hours with these Jamaican nurses, each of whom had had a child who had been killed, and they both chose to hold the space of the Great Mother. One of them lost her eighteen-year-old baby in a car accident and was sued by the so-called friends who survived, who were trying to eke out as much money as they could. Yes, of course the money was paid out by the insurance company, but not one survivor had any concern or compassion for their friend, who was dead, for the mother who had lost her baby. No, they cared about what they would get out of it, though their lives had been spared. Now that is satanic. Until each of us has the courage to look at our priorities …

The Apocalypse is not something out there that will eradicate everything on planet Earth. That would be far too simple. The Apocalypse is in each and every one of us. It takes courage to fight the beast. The beast is allegorical and rears its chameleon head when power is misused by each and every one of us. Sometimes we misuse power by not standing up for ourselves, by being powerless. That's the inverted beast—when you can't say no but you should because you're being asked to do something that you know isn't right for you, but you do it because you were never taught how to say no. You were never taught that sometimes the consequences of saying no are that the person that you've said no to will say you're not being a good friend, then will threaten to leave you or will just walk out on the relationship. So as they start to walk, then you start to buckle and you say, “No, don't go, don't go, I'm sorry—I just want to make it okay.” That's another form of the Apocalypse. This is

called spiritual slavery. You have just handed over an invisible leash that goes from your neck to their hands. Now, until we all have the courage to look at where we aren't choosing freedom for the soul, then we are out of alignment with the Great Mother and the Divine Father—whatever you want to call them. Sometimes the Great Mother seems to inhabit little people as well …

I have been writing about Grandma for days now. Tash finds me on the curve of the half-moon-shaped old Georgian stairs, sits down next to me, and says, “You need to stop work and come play now, Mum.” “Yeah, but Tash, I have a deadline.” “It'll be okay, Mum. Come on and play.” “Okay, Tash, which animal do you want me to be in the safari?” We play—Tash, Emily, Kelsey and I—down our hill on this huge rock in our garden that the kids dubbed “the safari.” And out of the blue Tash puts her hand in mine and says, “Do you know who we are Mum?” And at that moment I just look into her blue planets for eyes, and she says, “We are Daughters of Song, Mama.” And at that I jump up with new life, pick her up, and say, “Now let's go play”

_____