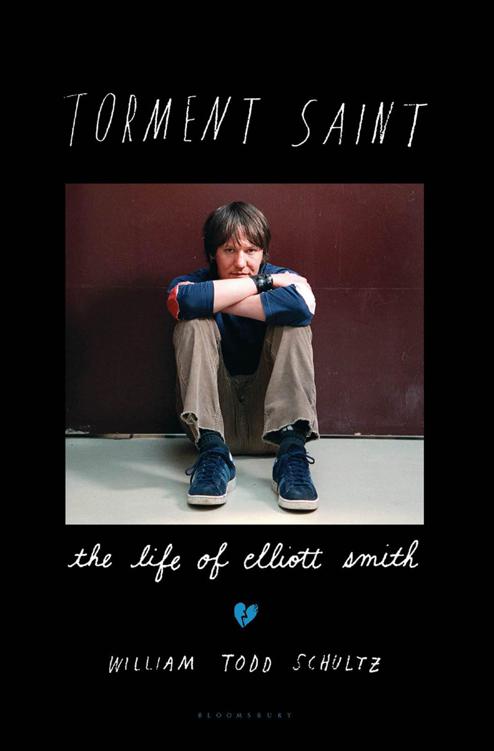

Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith

Read Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith Online

Authors: William Todd Schultz

For Adrienne

“For him, personally, his song is only a scream. Art for the artist is only suffering, through which he releases himself for further suffering. He is not a giant, but only a more or less brightly plumaged bird in the cage of his existence.”

—Kafka

“What is a poet? An unhappy man who hides deep anguish in his heart, but whose lips are so formed that when the sigh and cry pass through them, it sounds like lovely music … And people flock around the poet and say: ‘Sing again soon’—that is, ‘May new sufferings torment your soul but your lips be fashioned as before, for the cry would only frighten us, but the music, that is blissful.’”

—Kierkegaard

The intellect of man is forced to choose

Perfection of the life, or of the work

And if it take the second must refuse

A heavenly mansion, raging in the dark.

—Yeats

Chapter One: Hey Mister, That’s Me Up On the Jukebox

Chapter Three: Raining Violins

Chapter Four: Some Reverse Pyromaniac

Chapter Eight: A Symbol Meaning Infinity

Chapter Nine: Can’t Make a Sound

Coda: The Hero Killed the Clown

The Smith Myth

I was standing

on the concrete floor of storage locker 2010, near the Silver Lake portion of Los Angeles, surrounded by songwriter Elliott Smith’s things, and wondering where to turn to find him. He was here somewhere, but he was gone too, eight years gone, simultaneously present and absent, a strained melody. To the left was a plastic tub filled with T-shirts, many worn in performances. His personal vinyl records—

Elliott Smith

,

Either/Or

,

XO

—still in cellophane wrappers, were filed neatly in a cardboard box, five or six copies of each. Books piled up nearby, underlined and with notes in margins—

Physicians’ Desk Reference

s spanning several years, various fiction titles, an analysis of the effects of abuse on young boys. A bag beside the books contained prescription bottles, medications still inside—Serzone (for depression), Klonopin (for anxiety and seizures), Strattera (for ADHD). An electric guitar leaned on a stand, amplifiers and mixing boards ran up the right wall. Then there were his writings, scribbled on the backs of legal documents, on napkins, on random torn-off sheets of paper and Pee-Chee folders. I sat down and read through a hastily written but still lucid treatise on existence and nothingness, another on the failure of language to capture experience (“Language is like Legos: fun to work with but less useful”). Songs were also included, handwritten, in nascent or variant versions, original drafts to “Say Yes,” “King’s Crossing,” “Between the Bars,” and “A Distorted Reality’s Now a Necessity to be Free,” the last on sketch paper with what looked to be a cigarette burn in the center. All these things reposed, the life’s debris, its residue, the possessions of a person no longer around to animate them. Outside it rained hard; it would do so all day and night.

There are too many Elliott Smiths to count, too many anybodys to count, self a bulging multiplicity. There’s Texas Elliott, Portland Elliott, New York Elliott, Silver Lake Elliott. There’s Elliott in a basement on a hill,

underground with a stellar view. There’s Elliott between bars, Elliott in the studio, Elliott in his Prada suit, “dollared up in virgin white” at the Oscars. He’s clean, he’s wasted; he’s paranoid, he’s lucid; he’s fragile, in search of some situation where he’s better off than dead, or he’s a butterfly, spending the day higher than high. He’s drinking fortified green concoctions for his health, he’s extinguishing lit cigarettes in his flesh. He’s alive in the music and he’s dead, finding no good reason not to do it.

Which of these Elliotts is true, and which false? Are some more real than others, closer to the core? Those who never knew him, or knew him slightly, or only heard his music, which is all that remains now, are left with one, inevitably final option. We are interpreters. We are pattern finders. That is biography. It’s the connective tissue between facts. It’s the plot inferred, spread over messy, desultory life. It’s a true fiction. One approach was suggested by Elliott himself in the song “Stickman.” Spin the world on its flipside, and “listen backwards for meaning.” It may be the only path. It’s not possible to listen forward anymore.

Elliott was disarmingly bright, according to everyone who knew him, an avid reader of Dostoevsky, Kafka, Beckett, Stendhal, Freud, the Buddha, all of whom destabilized notions of identity. I think he knew how little we know about who we are. The idea comes through in lyrics. “I don’t know who I am,” he says simply; at times he wishes he were no one. He’s a stickman shooting blanks at emptiness, living with “one dimension dead.” He’s an invisible man with a see-through mind. He’s a junkyard full of false starts. He’s a ghost-writer, feeling hollow. “I lost my plot in a game of shells,” he writes in an early draft of “King’s Crossing.” There’s a sense, comforting and commonsensical, that if we want to know about someone, all we need to do is ask him. It’s not that easy. Sometimes he doesn’t know. Sometimes he doesn’t want to know. As Elliott said summarily: “Confusion is King/It’s the talk of my town.”

In any case, Elliott Smith is gone, dead from two knife wounds to the heart in October 2003.

1

If he had any answers, in a spasm of insight, any light to shed on the origins of his art—the astonishingly accomplished music he left behind—we can’t ask for them now. But that doesn’t mean we can’t know anything. We can. It’s there in the art, the music, where he lived most freely, most fearlessly, most authentically. The music keeps telling us who he is.

And what the music elicits—in me, in most everyone who hears it and takes to it—is a strangely comforting, sensual melancholy, a gentle sadness, the kind that comes with soft rain. It’s the same for all truly great dark art. There’s a pleasure in seeing our shadows paraded beautifully. It’s liberating to find them so prettily decked out, a sort of reverse Halloween. The repressed returns and it actually looks and sounds good. Like other shadow-driven artists—Sylvia Plath, for instance, or Diane Arbus—Elliott struggled with childhood traumas. He turned trauma into visionary aesthetic achievements—the art was trauma-fueled, trauma-determined. When Elliott died, he was hard at work recording songs for a double-album magnum opus on the order, he hoped, of the Beatles’

White Album

. This was to be a brand-new sound, full of unpretty noise, more corrosive and biting than anything he’d done before. If the songs seemed perfect he worked, according to David McConnell, who was there in the studio as Elliott assembled tracks, to fuck them up.

2

It was a kind of disfigurement. He was turning the pretty inside out, finding the ugly in it. He was turning himself inside out.

There are closer, more recent comparisons too (beyond Plath and Arbus), ones Elliott was asked about frequently while he was alive, as if, for interviewers, making sense of him required figuring out how he was not some simple, uninteresting duplication of what had gone before. By far the most obvious is Kurt Cobain, who died in 1994, when Elliott was 25 (Cobain was born in 1967, Smith in 1969). This was the year Elliott released his first solo album,

Roman Candle

, recorded on a four-track with a borrowed Le Domino guitar. Jennifer Chiba, Smith’s girlfriend at the time of his death, says Elliott romanticized and envied Cobain’s suicide. One night he actually dreamed of Courtney Love, according to a different friend. The context was sexual, but more too: Love signified fame. To have

her

, he realized later in thinking the dream over, was to have

it

. The Cobain obsession was less about Kurt, per se, than about what Kurt had managed to achieve, against pretty heavy odds. Plus, Cobain died at an apex. He built up a fabulous city, then blew it to hell—an atavistic impulse Elliott explored in the song “A Passing Feeling.” He gets into the same subject in draft lyrics for “King’s Crossing,” where an unnamed judge, appointed for life, delivers the following verdict: everyone should die in their prime.

Cobain was a talented child, a gifted artist with a room full of carefully

drawn cartoon characters (Aquaman, Donald Duck, Goofy). His parents divorced when he was eight, and it scarred him. He saw his mother and father as betrayers. The suicide option appeared early on; at age 15 he made a home movie titled “Kurt Cobain Commits Bloody Suicide.”

Just like Elliott, Cobain was drawn to the Beatles. He started singing “Hey Jude” by age two. His posthumously published journals mention John Lennon as an idol. In the 1980s he moved on to punk. Buzz Osborne of the Melvins—also from Aberdeen, Washington, Cobain’s hometown—turned him on to Black Flag and Bad Brains. The Pixies he connected with “so heavily that I should have been in that band”; he wrote “Smells Like Teen Spirit” in an attempt to “rip off” their singular alternating soft and loud dynamics, a musical form one finds in a number of Nirvana tracks.

It’s uncanny, the points of intersect between Smith’s and Cobain’s biographies. Both lived in the rainy, dreary Pacific Northwest, a climate that virtually breeds depression. (In fact, in 2008

Business Week

ranked “unhappiest cities” in the United States; Portland was number 1, Seattle number 20.) Both rejected the jock mentality of peers with whom they felt they had nothing in common. Daringly for high schoolers, Smith and Cobain befriended gay classmates. Cobain, in an interview with the

Advocate

, identified himself as “gay in spirit”: “I started being really proud of the fact that I was gay even though I wasn’t.” He relished pissing off homophobes, or anything else vaguely connected to mainstream, censorious attitudes. Both endured early divorce, its resulting feelings of abandonment and loss of security showing up regularly in songs. The songs were sometimes self-denigrating. Jarring for its time, Lennon wrote “I’m a Loser”; Cobain declared “I think I’m dumb” over and over in “Lithium”; Smith called himself “damaged bad at best.”

Kurt’s parents remarried, like Elliott’s did, and the new families occasioned resentment. The dark leitmotif of Elliott’s early life was a prevailing sense of mistreatment. Same for Cobain, who witnessed domestic violence against his mother, once hospitalized with a broken arm. Then there’s the most important parallel of all. Smith and Cobain transmogrified emotional trauma, twisted it into art. Anger and sadness were replaced by words and melodies. Music was a liminal space, a poultice, a confession made to millions. The way in became a way out; it worked, it had the potential to heal,

for a time. But the darkness got darker, more devouring. And somehow, for some reason, along the way it overpowered any creative use that might be made of it. It was a killer. Drugs were a neutralizer, they delivered a comforting nothingness, but they too were more death, a way of not feeling—which Elliott equated to failure—a way of not being alive.

There are two broad avenues for making sense of these commonalities. Milieu is one, the prevailing mid-1980s zeitgeist. Smith and Cobain played and hung out in the same clubs and bars, they absorbed similar punk, indie, anything-goes aesthetics. Satyricon, for instance, named after the Fellini film, was opened in 1983 by former cab driver George Touhouliotis in Portland’s Chinatown, a “real shithole” of a neighborhood with open drug dealing, fights, knives, guns.

3

“A mere attempt to walk the sidewalks … required a helmet and full body armor,” recalls local historian SP Clarke.

4

Heroin dealers, addicts, sociopaths, homeless, the mentally ill—all manner of malcontents loitered about in an atmosphere of chaos and incipient violence. Venturing into the club was genuinely scary; the fear and risk made the music more legit, more authentically vanguard. Most important bands came through the place, including Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Mudhoney, the Wipers, Dead Moon, Everclear, and later, Elliott’s Heatmiser—in short, “any group that was worth its weight in flannel, leather, or torn denim.”

5

“It was the Reagan era,” recalls booker Chris Monlux, “it was kind of a punk-rock time.” Touhouliotis wasn’t so much interested in the music. He was drawn, instead, to the culture, what the bands seemed to represent, which he characterized as freshness, realness. “God loves freshness,” he said. “He hates repetition.” Sam Coomes, who had come to Portland from San Francisco in the wake of The Donner Party, and who played with Elliott in Heatmiser after replacing original bassist Brandt Peterson, refers to the mid-80s as “the heroin days”: “It was more outré or something … It was truly underground. The people who frequented places like Satyricon were real fanatics.”

6

The goal, according to dancer Kitty Diggins, was mayhem. “We always had carte blanche to do whatever we wanted to do.” Club regular Fernando Viciconte remembers one emblematic night when the theme happened to be porn. Twelve TV sets transmitted sex acts onstage; offstage mushroom tea circulated. In this atmosphere of ubiquitous hardcore, Viciconte picked up a guitar with three strings, connected to a “small, shitty

Peavey amp.” He wasn’t feeling it, so he pulled down his pants and toyed with his balls on a chair. “I played three songs naked in front of mushroomed folks. I’d been in town a week.”

7