Tracking Bodhidharma (42 page)

Read Tracking Bodhidharma Online

Authors: Andy Ferguson

The city of Dengfeng, which rests amid Mount Song's peaks and valleys, now offers hotels for the legions of tourists that flock to visit the

place's most famous site, Shaolin Temple. The city is also famous for forty or so boarding academies that serve both as schools and training centers for young Chinese martial arts students. The city's name, Dengfeng, literally means “Ascendant Fiefdom,” but locals say this name is derived from an earlier term with the same pronunciation. In ancient times China's only empress, named Wu Zetian, loved to come from her court in Luoyang to visit and pay honor to Mount Song's Buddhist teachers. She would “ascend the peak,” which also is pronounced

deng feng

in Chinese. Wu Zetian, having never traveled too far from Luoyang, thought Mount Song to be the world's highest mountain.

place's most famous site, Shaolin Temple. The city is also famous for forty or so boarding academies that serve both as schools and training centers for young Chinese martial arts students. The city's name, Dengfeng, literally means “Ascendant Fiefdom,” but locals say this name is derived from an earlier term with the same pronunciation. In ancient times China's only empress, named Wu Zetian, loved to come from her court in Luoyang to visit and pay honor to Mount Song's Buddhist teachers. She would “ascend the peak,” which also is pronounced

deng feng

in Chinese. Wu Zetian, having never traveled too far from Luoyang, thought Mount Song to be the world's highest mountain.

Shaolin Temple is not simply the legendary home of the world's

kong fu

practitioners. It is known as the “birthplace” of Zen in China. According to the prevailing story, Bodhidharma came here after failing to come to an understanding with Emperor Wu and remained here for nine years, practicing his Zen meditation in a cave near Shaolin Temple.

kong fu

practitioners. It is known as the “birthplace” of Zen in China. According to the prevailing story, Bodhidharma came here after failing to come to an understanding with Emperor Wu and remained here for nine years, practicing his Zen meditation in a cave near Shaolin Temple.

Soon after I arrived last night on a bus from Zhengzhou City, a snowstorm blanketed the area. This morning the street in front of the hotel is frozen, and the few cars and pedestrians brave enough to venture out carefully inch their way along. Despite this, some taxis are still pursuing their livelihood, and I wave one to the side of the huge roundabout intersection near my hotel. We set off slowly into the mists toward the base of Song Mountain.

40. Shaolin Temple

ALTHOUGH THE TERM

kong fu

usually means “martial arts,” it may refer to any great skill or capacity. In Chinese there is an old verse about Bodhidharma that goes like this:

kong fu

usually means “martial arts,” it may refer to any great skill or capacity. In Chinese there is an old verse about Bodhidharma that goes like this:

Bodhidharma came from the west with a single word, “

Mu

!,”

Mu

!,”

The nature of mind was his only

kong fu

,

kong fu

,

Trying to grasp Dharma by using written words,

You'll drain Poting Lake to make the ink, but it still will never do!

The word

Mu

in the verse is a double entendre, since it literally means “no” or “none.” Thus the verse on the one hand means that Bodhidharma didn't bring a single word with him to China (no scriptures to study). But later the single word

mu

became the focus of a famous

mu koan

of Zen. In Japan and the West, many Zen students concentrate on this single word,

mu

, as part of their Zen training. So the verse above is a typical Chinese play on words with a clever two-fold meaning. This

mu

reference is also about the same word that the Japanese militarist Sugimoto employed to explain his worship of the Japanese emperor.

Mu

in the verse is a double entendre, since it literally means “no” or “none.” Thus the verse on the one hand means that Bodhidharma didn't bring a single word with him to China (no scriptures to study). But later the single word

mu

became the focus of a famous

mu koan

of Zen. In Japan and the West, many Zen students concentrate on this single word,

mu

, as part of their Zen training. So the verse above is a typical Chinese play on words with a clever two-fold meaning. This

mu

reference is also about the same word that the Japanese militarist Sugimoto employed to explain his worship of the Japanese emperor.

Shaolin Temple claims, through its connection with Bodhidharma, to be the home of both Zen and Chinese

kong fu

. From its earliest days, Shaolin was connected to the imperial court. Its founder, the Zen teacher

Fotuo, reportedly established the temple in 496 under the command and support of Emperor Xiao Wen of the Northern Wei dynasty, and thereafter Shaolin long represented the unity of the imperial throne and the Buddhist religion.

kong fu

. From its earliest days, Shaolin was connected to the imperial court. Its founder, the Zen teacher

Fotuo, reportedly established the temple in 496 under the command and support of Emperor Xiao Wen of the Northern Wei dynasty, and thereafter Shaolin long represented the unity of the imperial throne and the Buddhist religion.

Like Emperor Wu, Emperor Xiao Wen devoted himself to Buddhist sutra study, issues of doctrine, building temples, and ordaining monks and nuns. He proclaimed himself to be the Tathagata (Buddha), and he actively took part in religious life. In the year 476, for example, he ordained a group of a hundred monks and nuns, personally cutting their hair and enrobing them in a grand ceremony. He also sponsored vegetarian banquets for the Buddhist clergy. In 478, during one such banquet, he pardoned the country's condemned criminals. In 493, he established forty-seven precepts required to be taken by those entering monkhood.

Old records make clear that Emperor Xiao Wen was devoted to the study of Buddhist doctrines. He did not, however, forsake the study of Zen, as indicated by his enthusiasm for the Zen teacher Fotuo who established Shaolin Temple. Even before Shaolin temple was established, Emperor Xiao Wen built a large Zen monastery near his old northern capital city of Pingcheng where Fotuo could teach.

How can the fact that Bodhidharma is called the First Ancestor of Zen be reconciled with the fact that his contemporary Fotuo, who was also a non-Chinese of South Asian origin, was a Zen teacher? An explanation for this can be found in the Chinese Zen tradition itself. Fotuo is described as an advocate of Hinayana (“Little Vehicle”) Zen, as opposed to the more lofty Mahayana (“Great Vehicle”) Zen. But the alleged difference between Zen before Bodhidharma and Zen after Bodhidharma may simply be the result of politics. The earliest major Zen advocate in China was a monk named Anshigao who lived three centuries before Bodhidharma. He based his Zen practice on the Yin Chi Ru Sutra. A rendering of this scripture's name in English might be “Entering [the Way by] Practicing [supporting] the Mysterious [darkness].” The scripture taught “stillness [meditation] and observing.” Since Bodhidharma's own teaching was “observing the nature of the human mind,” through meditation, the alleged difference between early Chinese Hinayana Zen and Bodhidharma's Mahayana Zen seems to be

not too great. Bodhidharma's purported practice of “observing mind” doesn't look that much different from what came before him. Perhaps Bodhidharma, in line with his times, embraced the Bodhisattva ideal as indicated in his “Two Entrances and Four Practices” cited above. In any case, claims that Bodhidharma was the first Ancestor of Zen seem to have much to do with politics. The clear demarcation between his Zen and Emperor Wu's Imperial Zen is stark.

not too great. Bodhidharma's purported practice of “observing mind” doesn't look that much different from what came before him. Perhaps Bodhidharma, in line with his times, embraced the Bodhisattva ideal as indicated in his “Two Entrances and Four Practices” cited above. In any case, claims that Bodhidharma was the first Ancestor of Zen seem to have much to do with politics. The clear demarcation between his Zen and Emperor Wu's Imperial Zen is stark.

Under the Northern Wei Emperor's orders, Fotuo officially founded Shaolin Temple in the year 496. Presumably it took about two years to build the temple, so the date surrounding its establishment matches with the time when Bodhidharma's disciple Sengfu is recorded in the

Continued Biographies

to have departed from the same area. Bodhidharma and his disciples are said to have lived at a spot about a mile from Shaolin Temple that is now a small nunnery. In light of the

Continued Biographies

timeline that claims that Sengfu left the area in 494 and again in 496, the date recorded for when Shaolin Temple was built, the possibility that Bodhidharma and his monks were living at the place and decided to move when construction on the new temple began is worth considering. Tellingly, despite his association with the place, mention of Bodhidharma cannot be found in Shaolin Temple's early records. Also, there is no trace of him found in the court history of Emperor Xiao Wen. It seems he wasn't in the area, or at least had dropped out of sight, by the time that temple's construction was finished.

Continued Biographies

to have departed from the same area. Bodhidharma and his disciples are said to have lived at a spot about a mile from Shaolin Temple that is now a small nunnery. In light of the

Continued Biographies

timeline that claims that Sengfu left the area in 494 and again in 496, the date recorded for when Shaolin Temple was built, the possibility that Bodhidharma and his monks were living at the place and decided to move when construction on the new temple began is worth considering. Tellingly, despite his association with the place, mention of Bodhidharma cannot be found in Shaolin Temple's early records. Also, there is no trace of him found in the court history of Emperor Xiao Wen. It seems he wasn't in the area, or at least had dropped out of sight, by the time that temple's construction was finished.

Yet strangely, since the sixteenth century or so, the temple has claimed that Bodhidharma not only started Zen at this place, but

kong fu

as well. Where did the

kong fu

connection come from?

kong fu

as well. Where did the

kong fu

connection come from?

Popular folklore and some solid historical clues do connect Shaolin Temple to Chinese

kong fu

from early in its history, yet there is no evidence that Bodhidharma had anything to do with this. Scholars have suggested, and recent archeological evidence supports, the idea that the temple's

kong fu

began with a disciple of the temple's founder, Fotuo. That monk, named Seng Chou, one of the great Zen teachers cited and praised highly by Daoxuan, seems to have learned to defend himself from tigers in the mountains using a staff. This may be the origin of Shaolin Temple's famous

kong fu

.

SHAOLIN TEMPLE AND IMPERIAL-WAY BUDDHISMkong fu

from early in its history, yet there is no evidence that Bodhidharma had anything to do with this. Scholars have suggested, and recent archeological evidence supports, the idea that the temple's

kong fu

began with a disciple of the temple's founder, Fotuo. That monk, named Seng Chou, one of the great Zen teachers cited and praised highly by Daoxuan, seems to have learned to defend himself from tigers in the mountains using a staff. This may be the origin of Shaolin Temple's famous

kong fu

.

Uncertain folklore and

kong fu

notwithstanding, Shaolin Temple's close ties with China's emperors is a prominent feature of the temple's history. During the battles that established China's most illustrious and famous Tang dynasty (713â905), a handful of Shaolin's monks assisted the future Tang emperor Tai Zong (ruled 627â650) by stealthily capturing an enemy general. Later, this brave martial act was commemorated on a stele erected by that emperor, its text still proudly displayed at Shaolin Temple today.

kong fu

notwithstanding, Shaolin Temple's close ties with China's emperors is a prominent feature of the temple's history. During the battles that established China's most illustrious and famous Tang dynasty (713â905), a handful of Shaolin's monks assisted the future Tang emperor Tai Zong (ruled 627â650) by stealthily capturing an enemy general. Later, this brave martial act was commemorated on a stele erected by that emperor, its text still proudly displayed at Shaolin Temple today.

If the Tang emperors who lived long after Bodhidharma wanted to make a show of embracing his Zen tradition and co-opting it into their political sphere, then connecting him to Shaolin Temple in legend makes sense. It's easy to see why they would push that idea. By taking over the Zen tradition and declaring its origin to be in the imperial monastic system, they could bask in the light of Bodhidharma's popularity and also put an end to his tradition's irritating independent streak. Claiming that Bodhidharma was part of a place synonymous with Imperial-Way Buddhism helped consolidate imperial authority over that wayward religious element.

In this light, Shaolin's association with Bodhidharma reveals not the origin of Zen but his tradition's political capture by China's emperors.

Back in the present, my taxi creeps along the icy road and under a gray overcast and light snow. “Stop at the gas station on the left before we get to the temple,” I say. “My friend will meet me there.”

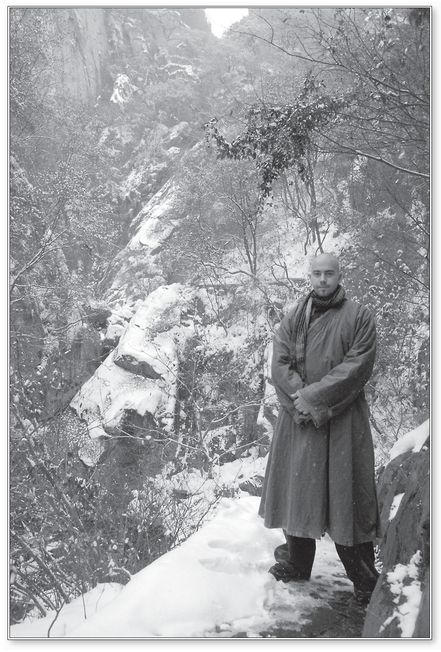

A young European man in the long thick winter frock of a monastic stands on the other side of the road next to the gas station. He is tall and has the bald head of a monk.

It must be Shanli. He greets me with a handshake and waves toward the back entrance gate of Shaolin Temple. “This way,” he says, his breath making a big cloud of steam in the winter air.

We set off into the valley where Shaolin Temple and its many related structures sit. The guard waves us past the side entrance gate where residents go in and out.

We begin to get acquainted by talking about our obvious common interest, Shaolin Temple history.

“Seng Chou, the third abbot of Shaolin, was the person who actually

started the

kong fu

tradition,” says Shanli. “There's no evidence that Bodhidharma had any part in it.”

started the

kong fu

tradition,” says Shanli. “There's no evidence that Bodhidharma had any part in it.”

“That's exactly what I've been telling people in my lectures for the past year,” I say. “You're the first person I've ever met that also says that!”

Shanli tells me how he arrived in China at the age of sixteen. In Leipzig, his home in what was previously Communist East Germany, he was an accomplished pianist, a student at the Bach Institute. When he arrived in China, he thought he would spend a year or so here. After two days in Beijing, he traveled to Shaolin Temple, where he has remained now for nearly twelve years. Now, at twenty-eight, he's spent long years in

kong fu

training, meditation, esoteric Buddhist practices, and learning to speak both Chinese and English fluently. He was only seven or eight years old when the Berlin Wall came down. He detests the society he lived in as a young child.

kong fu

training, meditation, esoteric Buddhist practices, and learning to speak both Chinese and English fluently. He was only seven or eight years old when the Berlin Wall came down. He detests the society he lived in as a young child.

“The Stasi [East German secret police] were the best spies in the world,” he says. “They had informers and files for everyone. People say I gave up living in one Communist society to come live in another one. But the truth is that my guruâis that the right word? There should be a better oneâanyway, my guru is transmitting something very special to me, and I don't dare leave now.”

We arrive at the main temple complex, and Shanli leads me to a side gate. We enter a small compound with a bronze statue of a bare-chested monk in the center of a courtyard. Chinese characters on the statue's torso depict the locations of energy meridians, all important for both

kong fu

and traditional Chinese medicine. At the side of the courtyard we enter a guest reception room.

kong fu

and traditional Chinese medicine. At the side of the courtyard we enter a guest reception room.

“Have a seat!” We sit at a burled wooden tea table, and two Shaolin monks already seated there serve us Chinese tea.

“That's Shaolin's finest,” says Shanli.

The hot tea pierces the frozen landscape of the deep winter day.

During the course of the afternoon, Shanli and I take a walk to a waterfall that is nestled in a nearby mountain gulley. The whole scene is covered with snow, and the water of the creek is frozen solid. It's obvious why Buddhist monks faced a living problem when they tried to establish Buddhism here in North China. No one could live outside in

conditions like this. It's just way too cold. But while Fotuo sought and used the emperor's funds to build Shaolin Temple and take refuge from the frigid winter, Bodhidharma was sitting in a cave somewhere up on the mountain behind us. No cushy politically compromised monastery for him!

conditions like this. It's just way too cold. But while Fotuo sought and used the emperor's funds to build Shaolin Temple and take refuge from the frigid winter, Bodhidharma was sitting in a cave somewhere up on the mountain behind us. No cushy politically compromised monastery for him!

Â

FIGURE 18. Shanli, near Shaolin Temple, 2009.

Other books

Sanctuary by Meg Cabot

Deadly Intent by Lynda La Plante

Face the Music: A Life Exposed by Stanley, Paul

Into The Fire (Gorgeous Entourage #1) by E. L. Todd

The Boxer by Jurek Becker

Home is Where the Heart is by Christie Mack

Rewind (Vanish Book Three) by Daise, Sonny

Dear Money by Martha McPhee

Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin

The Bull and the Spear - 05 by Michael Moorcock