Tracking Bodhidharma (45 page)

Read Tracking Bodhidharma Online

Authors: Andy Ferguson

After Emperor Xiao Wen died in the year 499, his palace on Mount Song was converted into a temple. Thereafter, it was home to several famous monks of various Buddhist schools. Most important, it may be the place where the Southern Zen school of Huineng came face-to-face with Buddhist establishment of the northern court in Luoyang. Mount

Song's Huishan temple may have been an important battleground in the struggle between Imperial Zen and the Zen of Bodhidharma, the Fourth Ancestor Daoxin, and Huineng, the Zen of just “observing mind.”

Song's Huishan temple may have been an important battleground in the struggle between Imperial Zen and the Zen of Bodhidharma, the Fourth Ancestor Daoxin, and Huineng, the Zen of just “observing mind.”

The parking lot at Huishan Temple is covered with snow. My taxi rolls gingerly into the virgin whiteness, and I negotiate a suitable fee to have the driver wait for me on an icy fall morning. From the parking lot, I ascend some steps and pass under a

paifang

that leads to the temple halls. But the place is no longer a practicing temple. It is now a museum that houses exhibits about some of Mount Song's most famous ancient monks. I make my way up the slope toward what was once the Heavenly Kings Hall. In front of it stand two bare-branched but nonetheless magnificent old gingko trees. According to the temple's records, they are more than fifteen hundred years old, which means they were planted when Emperor Xiao Wen established his palace here. Recently these and more than a hundred other ancient ginkgo trees that remain on Mount Song have been given special attention in order to preserve them. Like the tree I saw at Changlu Temple, they silently watch over Mount Song's ancient Buddhist sites. The earliest such gingko trees are at Fawang (“Dharma King”) Temple farther up the mountain. That place is another example of the Dharma King idea that long preceded Emperor Wuâthe Dharma King Temple on Mount Song was established in the years immediately following Buddhism's “official” introduction to China. The two Indian monks who legendarily brought Buddhism to China were present when those trees were planted in the first century.

paifang

that leads to the temple halls. But the place is no longer a practicing temple. It is now a museum that houses exhibits about some of Mount Song's most famous ancient monks. I make my way up the slope toward what was once the Heavenly Kings Hall. In front of it stand two bare-branched but nonetheless magnificent old gingko trees. According to the temple's records, they are more than fifteen hundred years old, which means they were planted when Emperor Xiao Wen established his palace here. Recently these and more than a hundred other ancient ginkgo trees that remain on Mount Song have been given special attention in order to preserve them. Like the tree I saw at Changlu Temple, they silently watch over Mount Song's ancient Buddhist sites. The earliest such gingko trees are at Fawang (“Dharma King”) Temple farther up the mountain. That place is another example of the Dharma King idea that long preceded Emperor Wuâthe Dharma King Temple on Mount Song was established in the years immediately following Buddhism's “official” introduction to China. The two Indian monks who legendarily brought Buddhism to China were present when those trees were planted in the first century.

But Huishan Temple's main hall and museum are closed today. The museum staff has wisely decided that no one is crazy enough to try to come for a visit with so much snow on the ground (not taking into consideration a history-obsessed foreigner). So further investigation about the mysterious monk who lived here, named Jingzang, will have to wait.

What I know already adds some interesting bits to the puzzle of Bodhidharma's Zen.

A few years ago I visited Huishan Temple for the first time and spent an afternoon studying displays about its famous monks. Among them was a monk named Lao An (“Old An”).

An

means “peace” or “safety.” He was a student of Zen's Fifth Ancestor, Hongren, whose temple is near Daoxin's at Huangmei.

An

means “peace” or “safety.” He was a student of Zen's Fifth Ancestor, Hongren, whose temple is near Daoxin's at Huangmei.

Ancient records say that Wu Zetian (China's only empress, to whom I referred earlier) respected Old An very highly, and she came to Mount Song on three occasions to honor him. She thereafter renamed this temple Anguo (“Peaceful Nation”) Temple. During about that time, Bodhidharma's Zen became a mainstream Buddhist religion at the nearby Tang dynasty “Eastern Capital” of Luoyang. There the monk Shenxiu, the leader of what was to be called the Northern and Gradual Zen school, along with his disciples, was expounding his Zen teachings. He taught at Luoyang's imperial court over the course of several years and reigning periods. Shenxiu would be known as the “Teacher of Three Emperors.”

I probably first read about Huishan Temple in the book

The Northern School and the Formation of Early Chan Buddhism

by the American Zen scholar John McCrae. In his book McCrae briefly discusses the obscure Zen master named Jingzang (“Pure Storehouse”) and the fact that his burial stupa is located at Huishan Temple. However, the temple really didn't catch my attention until years later when I was searching the Chinese Internet for texts from old Zen monuments. One fascinating stele was from Huishan Temple, where it was inscribed on Jingzang's burial stupa. What was fascinating was that the stele lists Jingzang as Zen's Seventh Ancestor and a student of the famous Sixth Ancestor Huineng. This was surprising, because Huineng had several famous students, but nowhere did I remember reading or hearing about one named Jingzang. He is a virtual Zen unknown. Naturally, after finding out about this burial stupa, I wanted to take a look at it and learn more about this obscure Seventh Ancestor of the Bodhidharma Zen tradition.

The Northern School and the Formation of Early Chan Buddhism

by the American Zen scholar John McCrae. In his book McCrae briefly discusses the obscure Zen master named Jingzang (“Pure Storehouse”) and the fact that his burial stupa is located at Huishan Temple. However, the temple really didn't catch my attention until years later when I was searching the Chinese Internet for texts from old Zen monuments. One fascinating stele was from Huishan Temple, where it was inscribed on Jingzang's burial stupa. What was fascinating was that the stele lists Jingzang as Zen's Seventh Ancestor and a student of the famous Sixth Ancestor Huineng. This was surprising, because Huineng had several famous students, but nowhere did I remember reading or hearing about one named Jingzang. He is a virtual Zen unknown. Naturally, after finding out about this burial stupa, I wanted to take a look at it and learn more about this obscure Seventh Ancestor of the Bodhidharma Zen tradition.

Thereafter, during my first opportunity to visit Huishan Temple, I asked the staff there to tell me exactly where Jingzang's old stupa was located so that I could take a look at it. They explained that the stupa was nearby but that it was closed to public viewing. When I asked if I could arrange to visit it, I was politely refused. I then explained that I was deeply interested in the history of this unknown Seventh Ancestor and furthermore I would be returning to the temple in about three weeks with a group from the United States that would want to see the stupa. This was actually true, as three weeks later I was scheduled to bring a group from the Los Angeles Zen Center to visit the area. I had not yet

told the group about the stupa, but I was sure they would want to see it. The man in charge at the museum gave me his card and told me he would see if this would be possible.

told the group about the stupa, but I was sure they would want to see it. The man in charge at the museum gave me his card and told me he would see if this would be possible.

During the days after that first visit to Huishan, I contacted some local friends who served as tour guides for groups I had previously brought to the area. I knew a local guide named Winston Wang, a young man who was also a Buddhist and who often accompanied my tour groups on visits to Shaolin Temple. If it were possible to visit the stupa, Winston could surely arrange it.

A few weeks later when I returned to Huishan Temple with the Los Angeles group, Winston accompanied us. He had contacted the local government antiquities bureau and arranged for one of its officials to meet us at Huishan Temple. Strangely, we were again politely told that visiting the stupa would not be possible because it was closed. I got a little animated, explaining to the local official that I had done research work concerning Jingzang and furthermore our group had traveled all the way from the United States to visit the place (along with many other places, of course). After they gave us more polite refusals, it finally came to light why the stupa was “closed.” Immediately west of Huishan Temple there is a Chinese military police base, and the stupa happens to rest within its boundaries. Allowing a group of American tourists to visit such a place was probably unprecedented if not unthinkable. Yet after more arguing, the local antiquities official, who apparently was well-acquainted with the base commander, seemed of two minds. He said it might be possible to ask the appropriate officials whether we could simply enter the base and visit the stupa, which was near the front gate, and not take pictures of anything except the stupa itself. I readily agreed with this idea. After a few mobile-phone calls, the official said we had received permission to enter the base and view the stupa.

It so happened that my friend Bill Porter, who is well-known in Chinese Buddhist circles, was helping me lead this particular group in China, and our group was being filmed by a Chinese television film crew that was documenting his experiences. The crew had been with us for several days. Naturally, they were forced to remain behind as our group made its way along a road and up a hill to the military base's front gate. There, the guards who had been informed of our arrival literally crouched on top of their German shepherd guard dogs, muzzling their

mouths to keep them from barking as our group passed under the gate and into the restricted area.

mouths to keep them from barking as our group passed under the gate and into the restricted area.

Happily, the stupa was not within sight of any military facilities but simply sat right next to the base entrance road. I was walking at the rear of the group to make sure everyone got into the place without any problems and then hurried forward to catch up. The road made a sharp left turn, and when I came around the corner I saw an astonishing sight. Even from a long distance I could see that Jingzang's stupa was far bigger than I was expecting. Its photo on the Internet did not convey its size. It was way bigger than an individual monk's stupa would normally be from that era, larger than any such stupas in the famous “Pagoda Forest” at Shaolin Temple or scores of other temples I had visited. I started yelling “Look at that! That's a big stupa! Look at the size of that thing!” Others in the group looked at me as if I were a little strange. I suppose they didn't know how big such monuments normally were and didn't realize what we were seeing.

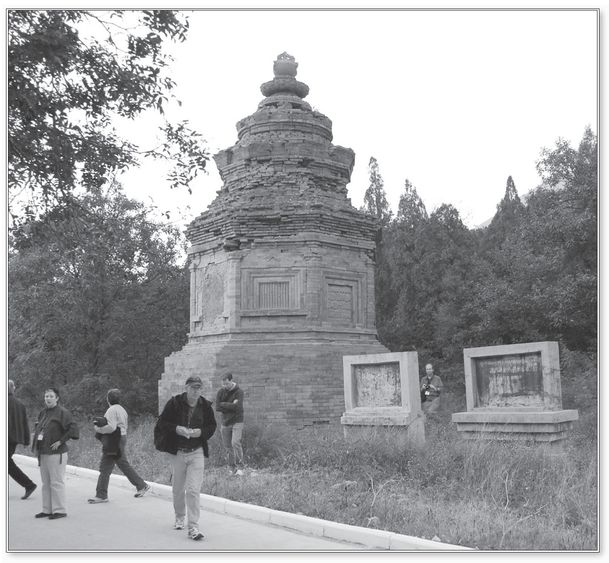

Jingzang's burial stupa is nearly ten meters tall and sits on a base about six meters wide. Chinese archeologists say its special octagonal architecture, which came from South Asia, is all but unknown elsewhere in the country. While the famous murals in the Dunhuang Caves, far out on the Silk Road, depict stupas of this ancient design, almost none remaisn in existence. One of the few exceptions was this stupa.

What was most amazing is its great size, which naturally means the person it honored must have been considered especially important. Suddenly the claim of Jingzang being Zen's Seventh Ancestor seemed plausible, a claim that might be more than hyperbole written by grief-stricken disciples.

For the next fifteen minutes or so we examined this ancient, virtually unknown relic of the Zen tradition. Traces of ancient carvings could be seen on the different faces of the stupa. Obviously, when it was built it was not only big but also elaborately carved and decorated. We circumambulated the structure and took multiple photos. I was the most excited of anyone in the tour group. I had a sense that we were seeing the symbol of a genuine mystery of great importance. What could that importance have been?

Jingzang's stupa may reveal that he was a unique, even pivotal, figure of his time. This could have big implications for Bodhidharma's Zen

and its historical meaning. No similar stupa remains in the area, and, as I said, no other stupa of similar purpose compares to Jingzang's in size and design. Moreover, constructing such a structure required lots and lots of money. Who paid for it? We have little record about this teacher except the text that was left on the memorial itself.

and its historical meaning. No similar stupa remains in the area, and, as I said, no other stupa of similar purpose compares to Jingzang's in size and design. Moreover, constructing such a structure required lots and lots of money. Who paid for it? We have little record about this teacher except the text that was left on the memorial itself.

Â

FIGURE 21. Stupa near Huishan Temple, Mt. Song, for Jingzang, Zen's Unknown Seventh Ancestor.

After that visit I did more research on the stupa and the text that it held. Although the original stele is now nearly unreadable, the original text was, happily, recorded in various books and historical records that remain available today. I found some scholarly works about these old records and managed to get a copy of the stele's original text. There are some key discrepancies in the three records generally available for scholarly research. Despite this, an outline of Jingzang's story can be teased out of the textual evidence.

The stele is a contemporary record of a monk directly connected to the Sixth Ancestor Huineng. This is unique, since other records of his

students are all from secondary sources. The stele directly states that Jingzang was Huineng's Dharma heir.

students are all from secondary sources. The stele directly states that Jingzang was Huineng's Dharma heir.

But Jingzang's stele also has some confusing, somewhat contradictory information, especially with regard to dates. It seems likely the disciples who engraved the stone were uncertain of exactly when certain events happened in the course of his life. Nevertheless, I think the basic information on the memorial must be a more or less genuine account of this mysterious “Seventh Ancestor” of Zen.

The stele relates that the monk Jingzang was born in the year 675 and died in the year 746 at the age, by Chinese reckoning, of seventy-two (Chinese traditionally count someone as one year old upon the first New Year's Day after their birth). Jingzang became a home-leaving monk at the age of nineteen and studied the Diamond, Lankavatara, and other sutras. He then traveled to Mount Song where he studied under Old An, the monk I introduced earlier, who was honored by the Chinese empress Wu Zetian. The stele says he remained with his teacher Old An for more than ten years. Then, after Old An died in the year 708, Jingzang traveled south to Nanhua Temple to become a student of the Sixth Zen Ancestor Huineng. The stele says that when Jingzang asked Huineng about the Buddha Way, Huineng responded in a manner that caused Jingzang to “flow tears” (indicating an awakening experience). Thereafter, Jingzang traveled to a place called Jingnan (an area of north Hunan Province that sits just south of the Yang-tse River). There he studied for a time under an otherwise unknown teacher named Du. Jingzang then returned to Huineng's Nanhua Temple where he received full transmission as a spiritual heir, “receiving the seal [of transmission], the Dharma, and the lamp” (a term for Zen's so-called mind-to-mind transmission of the Zen Way). He then lived at a place called Jade Buddha Woods on Great Hero Mountain (I don't know if this is the same Great Hero Mountain where Baizhang Temple is located).

Jingzang's reputation then spread widely, and he ultimately returned to Huishan Temple on Mount Song and took up residence in a hall named after his previous teacher Old An. There he remained during the last years of his life, “converting the area of Luoyang and the Yellow River,” and becoming “widely known as the Seventh Ancestor that has arisen from Mount Song.” The stele claims, significantly, that Jingzang did not fear undertaking exhaustive efforts to spread his teaching and

advanced the doctrine of Sudden Enlightenment, the line of Zen represented by Huineng, Baizhang, and other Southern school teachers of Bodhidharma's main lineage.

advanced the doctrine of Sudden Enlightenment, the line of Zen represented by Huineng, Baizhang, and other Southern school teachers of Bodhidharma's main lineage.

Other books

A Country Mouse by Fenella Miller

Like Glass We Break (Glass #2) by Kari Fisher

Tom Paine Maru - Special Author's Edition by L. Neil Smith

Every Woman's Dream by Mary Monroe

Queen (Mistress & Master of Restraint) by Erica Chilson

The Recruiter (A Thriller) by Amore, Dani

Never a Perfect Moment by Cathy Cole

Getting Old Is a Disaster by Rita Lakin

The Jane Austen Book Club by Karen Joy Fowler