Travels into the Interior of Africa

Read Travels into the Interior of Africa Online

Authors: Mungo Park,Anthony Sattin

the Interior

of Africa

MUNGO PARK

With afterwords by Anthony Sattin

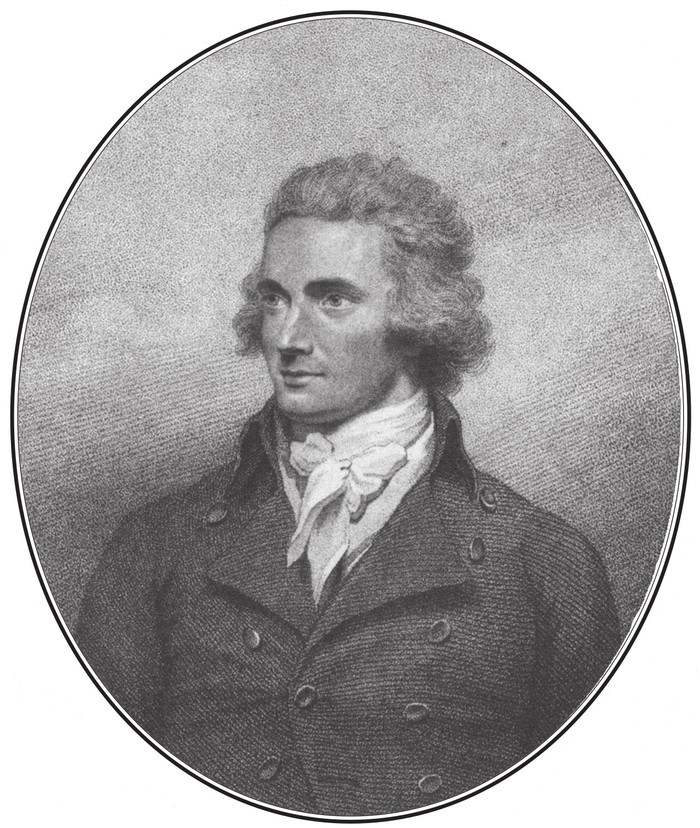

MUNGO PARK

From an engraving after the portrait by Henry Ederidge reproduced as the frontispiece to the Travels

T

HE FOLLOWING JOURNAL

, drawn up from original minutes and notices made at the proper moment, and preserved with great difficulty, is now offered to the Public by the direction of my noble and honourable employers, the Members of the African Association. I regret that it is so little commensurate to the patronage I have received. As a composition, it has nothing to recommend it but

truth

. It is a plain unvarnished tale, without pretensions of any kind, except that it claims to enlarge, in some degree, the circle of African geography. For this purpose my services were offered, and accepted by the Association; and, I trust, I have not laboured altogether in vain. The work, however, must speak for itself; and I should not have thought any preliminary observations necessary, if I did not consider myself called upon, both by justice and gratitude, to offer those which follow.

Immediately after my return from Africa, the Acting Committee of the Association,

*

taking notice of the time it would require to prepare an account in detail, as it now appears, and being desirous of gratifying, as speedily as possible, the curiosity which many of the Members were pleased to express concerning my discoveries, determined that an epitome, or abridgment of my travels, should be forthwith prepared from such materials and oral communications as I could furnish, and printed for the use of the Association, and also that an engraved map of my route should accompany it. A memoir, thus supplied and improved, was accordingly drawn up in two parts, by members of the Association, and distributed among the Society; the first consisting of a narrative, in abstract, of my travels, by Bryan Edwards, Esq; the second, of Geographical Illustrations of my progress, by Major James Rennell,

FRS

. Major Rennell was pleased also to add a map of my route, constructed in conformity to my own observations and sketches, freed from those errors which the Major’s superior knowledge, and distinguished accuracy in geographical researches, enabled him to discover and correct.

Availing myself, therefore, on the present occasion, of assistance like this, it is impossible that I can present myself before the public, without expressing how deeply and gratefully sensible I am of the honour and advantage which I derive from the labours of those gentlemen; for Mr Edwards has kindly permitted me to incorporate, as occasion offered, the whole of his narrative into different parts of my work; and Major Rennell, with equal goodwill, allows me to embellish and elucidate my Travels with the map before mentioned.

Thus aided and encouraged, I should deliver this volume to the world with that confidence of a favourable reception, which no merits of my own could authorise me to claim, were I not apprehensive that expectations have been formed by some of my subscribers, of discoveries to be unfolded which I have not made, and of wonders to be related of which I am utterly ignorant. There is danger that those who feel a disappointment of this nature, finding less to astonish and amuse in my book than they had promised to themselves beforehand, will not even allow me the little merit which I really possess. Painful as this circumstance may prove to my feelings, I shall console myself under it, if the distinguished persons, under whose auspices I entered on my mission, shall allow that I have executed the duties of it to their satisfaction; and that they consider the Journal, which I have now the honour to present to them, to be, what I have endeavoured to make it, an honest and faithful report of my proceedings and observations in their service, from the outset of my journey to its termination.

M. P.

The following African words recurring very frequently in the course of the narrative, it is thought necessary to prefix an explanation of them for the reader’s convenience.

| Alkaid | The head magistrate of a town or province, whose office is commonly hereditary |

| Baloon | A room in which strangers are commonly lodged |

| Bar | Nominal money: a single bar is equal in value to two shillings sterling or hereabouts |

| Bentang | A sort of stage, erected in every town, answering the purpose of a town-hall |

| Bushreen | A Mussulman |

| Calabash | A species of gourd, of which the Negroes make bowls and dishes |

| Coffle or Cafila | A caravan of slaves, or a company of people travelling with any kind of merchandise |

| Cowries | Small shells, which pass for money in the interior |

| Dooty | Another name for the chief magistrate of a town or province; this word is used only in the interior countries |

| Kafir | A Pagan native; an unbeliever |

| Korree | A watering place where shepherds keep their cattle |

| Kouskous | A dish prepared from boiled corn |

| Mansa | A king or chief governor |

| Minkalli | A quantity of gold, nearly equal in value to ten shillings sterling |

| Paddle | A sort of hoe used in husbandry |

| Palaver | A court of justice; a public meeting of any kind |

| Saphie | An amulet or charm |

| Shea tou-lou | Vegetable butter |

| Slatees | Free black merchants, who trade chiefly in slaves |

| Soofroo | A skin for containing water |

| Sonakee | Another term for an unconverted native; it signifies one who drinks strong liquors, and is used by way of reproach |

*

This Committee consists of the following noblemen and gentlemen: Earl of Moira, Lord Bishop of Landaff, Right Hon. Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, Andrew Stewart, Esq.,

FRS

, and Bryan Edwards, Esq.,

FRS

. Concerning the original institution of the Society itself, and the progress of discovery, previous to my expedition, the fullest information has already been given in the various publications which the Society have caused to be made.

BOOK ONE

Travels in the interior districts of Africa performed under the direction and patronage of the African association in the years 1795, 1796, and 1797

by Mungo Park,

SURGEON

The Author’s motives for undertaking the voyage – His instructions and departure – Arrives at Jillifree, on the Gambia River – Proceeds to Vintain – Some account of the Feloops – Proceeds up the river for Jonkakonda – Arrives at Dr Laidley’s – Some account of Pisania, and the British factory established at that place – The Author’s employment during his stay at Pisania – His sickness and recovery – The country described – Prepares to set out for the interior.

S

OON AFTER MY RETURN

from the East Indies in 1793, having learnt that the noblemen and gentlemen, associated for the purpose of prosecuting discoveries in the interior of Africa, were desirous of

engaging

a person to explore that continent by the way of the Gambia River, I took occasion, through means of the President of the Royal Society, to whom I had the honour to be known, of offering myself for that service. I had been informed, that a gentleman of the name of Houghton, a captain in the army, and formerly fort-major at Goree, had already sailed to the Gambia, under the direction of the Association, and that there was reason to apprehend he had fallen a sacrifice to the climate, or perished in some contest with the natives; but this intelligence, instead of deterring me from my purpose, animated me to persist in the offer of my services with the greater solicitude. I had a passionate desire to examine into the productions of a country so little known, and to become experimentally acquainted with the modes of life and character of the natives. I knew that I was able to bear fatigue; and I relied on my youth and the strength of my constitution to preserve me from the effects of the climate. The salary which the Committee allowed was sufficiently large, and I made no stipulation for future reward. If I should perish in my journey, I was willing that my hopes and expectations should perish with me; and if I should succeed in rendering the geography of Africa more familiar to my countrymen, and in opening to their ambition and industry new sources of wealth, and new channels of commerce, I knew that I was in the hands of men of honour, who would not fail to bestow that remuneration which my successful services should appear to them to merit. The Committee of the Association, having made such enquiries as they thought necessary, declared themselves satisfied with the qualifications that I possessed, and accepted me for the service; and with that liberality which on all occasions distinguishes their conduct, gave me every

encouragement

which it was in their power to grant, or which I could with propriety ask.

It was at first proposed that I should accompany Mr James Willis, who was then recently appointed Consul at Senegambia, and whose countenance in that capacity it was thought might have served and protected me; but Government afterwards rescinded his appointment, and I lost that advantage. The kindness of the Committee, however, supplied all that was necessary. Being favoured by the Secretary of the Association, the late Henry Beaufoy, Esq., with a recommendation to Dr John Laidley (a gentleman who had resided many years at an English factory on the banks of the Gambia), and furnished with a letter of credit on him for £200, I took my passage in the brig

Endeavour

, a small vessel trading to the Gambia for bees-wax and ivory, commanded by Captain Richard Wyatt, and I became impatient for my departure.

My instructions were very plain and concise. I was directed, on my arrival in Africa, ‘to pass on to the river Niger, either by the way of Bambouk, or by such other route as should be found most convenient. That I should ascertain the course, and, if possible, the rise and

termination

of that river. That I should use my utmost exertions to visit the principal towns or cities in its neighbourhood, particularly Timbuctoo and Houssa; and that I should be afterwards at liberty to return to Europe, either by the way of the Gambia, or by such other route, as, under all the then existing circumstances of my situation and prospects, should appear to me to be most advisable.’

We sailed from Portsmouth on the 22nd day of May 1795. On the 4th of June we saw the mountains over Mogadore, on the coast of Africa; and on the 21st of the same month, after a pleasant voyage of thirty days, we anchored at Jillifree, a town on the northern bank of the river Gambia, opposite to James’s Island, where the English had formerly a small port.

The kingdom of Barra, in which the town of Jillifree is situated, produces great plenty of the necessaries of life; but the chief trade of the inhabitants is in salt; which commodity they carry up the river in canoes as high as Barraconda, and bring down in return Indian corn, cotton cloths, elephants’ teeth, small quantities of gold dust, etc The number of canoes and people constantly employed in this trade, make the King of Barra more formidable to Europeans than any other chieftain on the river; and this circumstance probably encouraged him to establish those exorbitant duties which traders of all nations are obliged to pay at entry, amounting to nearly £20 on every vessel, great and small. These duties or customs are generally collected in person by the Alkaid, or governor of Jillifree, and he is attended on these occasions by a numerous train of dependants, among whom are found many who, by their frequent intercourse with the English, have acquired a smattering of our language; but they are commonly very noisy and very troublesome – begging for every thing they fancy with such earnestness and importunity, that traders, in order to get quit of them, are frequently obliged to grant their requests.

On the 23rd we departed from Jillifree, and proceeded to Vintain, a town situated about two miles up a creek on the southern side of the river. This is much resorted to by Europeans, on account of the great quantities of bees-wax which are brought hither for sale. The wax is collected in the woods by the Feloops, a wild and unsociable race of people; their country, which is of considerable extent, abounds in rice; and the natives supply the traders, both on the Gambia and Cassamansa rivers, with that article, and also with goats and poultry, on very reasonable terms. The honey which they collect is chiefly used by themselves in making a strong intoxicating liquor, much the same as the mead which is produced from honey in Great Britain.

In their traffic with Europeans, the Feloops generally employ a factor or agent, of the Mandingo nation, who speaks a little English, and is acquainted with the trade of the river. This broker makes the bargain; and, with the connivance of the European, receives a certain part only of the payment, which he gives to his employer as the whole; the remainder (which is very truly called the

cheating money)

he receives when the Feloop is gone, and appropriates to himself, as a reward for his trouble.

The language of the Feloops is appropriate and peculiar; and as their trade is chiefly conducted, as has been observed, by Mandingoes, the Europeans have no inducement to learn it. The numerals are as follow: One,

Enory

; Two,

Sickaba

or

Cookaba

; Three,

Sisajee

; Four,

Sibakeer

; Five,

Footuck

; Six,

Footuck-Enory

; Seven,

Footuck-Cookaba

; Eight,

Footuck-Sisajee

; Nine,

Footuck-Sibakeer

; Ten,

Sibankonyen

.

On the 26th we left Vintain, and continued our course up the river, anchoring whenever the tide failed us, and frequently towing the vessel with the boat. The river is deep and muddy, the banks are covered with impenetrable thickets of mangrove, and the whole of the adjacent country appears to be flat and swampy.

The Gambia abounds with fish, some species of which are excellent food; but none of them that I recollect are known in Europe. At the entrance from the sea, sharks are found in great abundance; and higher up, alligators and the hippopotamus (or river horse) are very numerous. The latter might with more propriety be called the river-elephant, being of enormous and unwieldy bulk, and its teeth furnish good ivory. This animal is amphibious, with short and thick legs, and cloven hoofs: it feeds on grass, and such shrubs as the banks of the river afford, boughs of trees, etc, seldom venturing far from the water, in which it seeks refuge on hearing the approach of man. I have seen many, and always found them of a timid and inoffensive disposition.

In six days after leaving Vintain, we reached Jonkakonda, a place of considerable trade, where our vessel was to take in part of her lading. The next morning, the several European traders came from their different factories to receive their letters, and learn the nature and amount of the cargo; and the captain despatched a messenger to Dr Laidley to inform him of my arrival. He came to Jonkakonda the morning following, when I delivered him Mr Beaufoy’s letter, and he gave me a kind invitation to spend my time at his house until an opportunity should offer of prosecuting my journey. This invitation was too acceptable to be refused; and being furnished by the Doctor with a horse and guide, I set out from Jonkakonda at daybreak on the 5th of July, and at eleven o’clock arrived at Pisania, where I was accommodated with a room and other conveniences in the Doctor’s house.

Pisania is a small village in the king of Yany’s dominions, established by British subjects as a factory for trade, and inhabited solely by them and their black servants. It is situated on the banks of the Gambia, sixteen miles above Jonkakonda. The white residents, at the time of my arrival there, consisted only of Dr Laidley, and two gentlemen who were brothers, of the name of Ainslie, but their domestics were numerous. They enjoyed perfect security under the king’s protection; and being highly esteemed and respected by the natives at large, wanted no accommodation or comfort which the country could supply; and the greatest part of the trade in slaves, ivory, and gold, was in their hands.

Being now settled for some time at my ease, my first object was to learn the Mandingo tongue, being the language in almost general use throughout this part of Africa; and without which I was fully convinced that I never could acquire an extensive knowledge of the country or its inhabitants. In this pursuit I was greatly assisted by Dr Laidley, who, by a long residence in the country, and constant intercourse with the natives, had made himself completely master of it. Next to the language, my great object was to collect information concerning the countries I intended to visit. On this occasion I was referred to certain traders called Slatees. These are free black merchants, of great consideration in this part of Africa, who come down from the interior countries chiefly with enslaved Negroes for sale; but I soon discovered that very little dependence could be placed on the accounts they gave; for they contradicted each other in the most important particulars, and all of them seemed extremely unwilling that I should prosecute my journey. These circumstances increased my anxiety to ascertain the truth from my own personal observations.

In researches of this kind, and in observing the manners and customs of the natives, in a country so little known to the nations of Europe, and furnished with so many striking and uncommon objects of nature, my time passed not unpleasantly; and I began to flatter myself that I had escaped the fever, or seasoning, to which Europeans, on their first arrival in hot climates, are generally subject. But, on the 31st of July, I imprudently exposed myself to the night dew, in observing an eclipse of the moon, with a view to determine the longitude of the place; the next day I found myself attacked with a smart fever and delirium; and such an illness followed, as confined me to the house during the greatest part of August. My recovery was very slow; but I embraced every short interval of convalescence to walk out, and make myself acquainted with the productions of the country. In one of those excursions, having rambled farther than usual in a hot day, I brought on a return of my fever, and on the 10th of September I was again confined to my bed. The fever, however, was not so violent as before; and in the course of three weeks I was able, when the weather would permit, to renew my botanical excursions; and when it rained, I amused myself with drawing plants, etc, in my chamber. The care and attention of Dr Laidley contributed greatly to alleviate my sufferings; his company and

conversation

beguiled the tedious hours during that gloomy season, when the rain falls in torrents; when suffocating heats oppress by day, and when the night is spent by the terrified traveller in listening to the croaking of frogs (of which the numbers are beyond imagination), the shrill cry of the jackal, and the deep howling of the hyena; a dismal concert, interrupted only by the roar of such tremendous thunder as no person can form a conception of but those who have heard it.

The country itself, being an immense level, and very generally covered with woods, presents a tiresome and gloomy uniformity to the eye; but although nature has denied to the inhabitants the beauties of romantic landscapes, she has bestowed on them, with a liberal hand, the more important blessings of fertility and abundance. A little attention to cultivation procures a sufficiency of corn; the fields afford a rich pasturage for cattle; and the natives are plentifully supplied with excellent fish, both from the Gambia river and the Walli creek.

The grains which are chiefly cultivated are Indian corn (

zea mays

); two kinds of

holcus spicatus

, called by the natives

soono

and

sanio

;

holcus

niger,

and

holcus

bicolor

; the former of which they have named

bassi

woolima

, and the latter

bassiqui

. These, together with rice, are raised in considerable quantities; besides which the inhabitants in the vicinity of the towns and villages have gardens which produce onions, calavances, yams, cassavi, ground-nuts, pompions, gourds, water melons, and some other esculent plants.