Travels into the Interior of Africa (23 page)

Read Travels into the Interior of Africa Online

Authors: Mungo Park,Anthony Sattin

The fourth cause above enumerated is

the commission of crimes, on which the laws of the country affix slavery as a punishment.

In Africa, the only offences of this class are murder, adultery, and witchcraft; and I am happy to say that they did not appear to me to be common. In cases of murder, I was informed that the nearest relation of the deceased had it in his power, after conviction, either to kill the offender with his own hand, or sell him into slavery. When adultery occurs, it is generally left to the option of the person injured, either to sell the culprit, or accept such a ransom for him as he may think equivalent to the injury he has sustained. By witchcraft is meant pretended magic, by which the lives or healths of persons are affected; in other words, it is the administering of poison. No trial for this offence, however, came under my observation while I was in Africa, and I therefore suppose that the crime and its punishment occur but very seldom.

When a free man has become a slave by any one of the causes before mentioned, he generally continues so for life, and his children (if they are born of an enslaved mother) are brought up in the same state of servitude. There are, however, a few instances of slaves obtaining their freedom, and sometimes even with the consent of their masters; as by performing some singular piece of service, or by going to battle, and bringing home two slaves as a ransom; but the common way of regaining freedom is by escape; and when slaves have once set their minds on running away, they often succeed. Some of them will wait for years before an opportunity presents itself, and during that period show no signs of discontent. In general, it may be remarked, that slaves who come from a hilly country, and have been much accustomed to hunting and travel, are more apt to attempt their escape than such as are born in a flat country, and have been employed in cultivating the land.

Such are the general outlines of that system of slavery which prevails in Africa, and it is evident, from its nature and extent, that it is a system of no modern date. It probably had its origin in the remote ages of antiquity, before the Mohammedans explored a path across the desert. How far it is maintained and supported by the slave traffic, which for two hundred years the nations of Europe have carried on with the natives of the coast, it is neither within my province nor in my power to explain. If my sentiments should be required concerning the effect which a discontinuance of that commerce would produce on the manners of the natives, I should have no hesitation in observing, that, in the present unenlightened state of their minds, my opinion is, the effect would neither be so extensive or beneficial as many wise and worthy persons fondly expect.

*

In time of famine, the master is permitted to sell one or more of his domestics, to purchase provisions for his family; and in case of the master’s insolvency, the domestic slaves are sometimes seized upon by the creditors, and if the master cannot redeem them, they are liable to be sold for payment of his debts. These are the only cases that I recollect, in which the domestic slaves are liable to be sold, without any misconduct or demerit of their own.

*

This is a large spreading tree (a species of

sterculia

) under which the Bentang is commonly placed.

*

When a Negro takes up goods on credit from any of the Europeans on the coast, and does not make payment at the time appointed, the European is authorised, by the laws of the country, to seize upon the debtor himself, if he can find him; or, if he cannot be found, on any person of his family; or, in the last resort, on

any native of the same kingdom

. The person thus seized on is detained, while his friends are sent in quest of the debtor. When he is found, a meeting is called of the chief people of the place, and the debtor is compelled to ransom his friend by fulfilling his engagements. If he is unable to do this, his person is immediately secured and sent down to the coast, and the other released. If the debtor cannot be found, the person seized on is obliged to pay double the amount of the debt, or is himself sold into slavery. I was given to understand, however, that this part of the law is seldom enforced.

Of gold dust, and the manner in which it is collected – Process of washing it – Its value in Africa – Of Ivory – Surprise of the Negroes at the eagerness of the Europeans for this commodity – Scattered teeth frequently picked up in the woods – Mode of hunting the elephant – Some reflections on the unimproved state of the country, etc

T

HOSE VALUABLE COMMODITIES

, gold and ivory (the next objects of our enquiry) have probably been found in Africa from the first ages of the world. They are reckoned among its most important productions in the earliest records of its history.

It has been observed, that gold is seldom or never discovered, except in

mountainous

and

barren

countries; nature, it is said, thus making amends in one way for her penuriousness in the other. This, however, is not wholly true. Gold is found in considerable quantities throughout every part of Manding – a country which is indeed hilly, but cannot properly be called

mountainous

, much less

barren

. It is also found in great plenty in Jallonkadoo (particularly about Boori), another hilly, but by no means an infertile country. It is remarkable that in the place last mentioned (Boori), which is situated about four days’ journey to the south-west of Kamalia, the salt market is often supplied, at the same time, with rock-salt from the Great Desert, and sea-salt from the Rio-Grande; the price of each, at this distance from its source, being nearly the same; and the dealers in each, whether Moors from the north, or Negroes from the west, are invited thither by the same motives – that of bartering their salt for gold.

The gold of Manding, so far as I could learn, is never found in any matrix or vein, but always in small grains, nearly in a pure state, from the size of a pin’s head to that of a pea, scattered through a large body of sand or clay; and in this state it is called by the Mandingoes

sanoo munko

, ‘gold powder’. It is, however, extremely probable, by what I could learn of the situation of the ground, that most of it has originally been washed down by repeated torrents from the neighbouring hills.

The manner in which it is collected is nearly as follows: about the beginning of December, when the harvest is over, and the streams and torrents have greatly subsided, the Mansa, or chief man of the town, appoints a day to begin

sanoo koo

, ‘gold washing’; and the women are sure to have themselves in readiness by the time appointed. A hoe, or spade, for digging up the sand, two or three calabashes for washing it in, and a few quills for containing the gold dust, are all the implements necessary for the purpose. On the morning of their departure, a bullock is killed for the first day’s entertainment, and a number of prayers and charms are used to ensure success; for a failure on that day is thought a bad omen. The Mansa of Kamalia, with fourteen of his people, were, I remember, so much disappointed in their first day’s washing, that very few of them had resolution to persevere, and the few that did had but very indifferent success, which, indeed, is not much to be wondered at, for instead of opening some untried place, they continued to dig and wash in the same spot where they had dug and washed for years, and where, of course, but few large grains could be left.

The washing the sands of the streams is by far the easiest way of obtaining the gold dust; but in most places the sands have been so narrowly searched before, that unless the stream takes some new course, the gold is found but in small quantities. While some of the party are busied in washing the sands, others employ themselves farther up the torrent, where the rapidity of the stream has carried away all the clay, sand, etc, and left nothing but small pebbles. The search among these is a very troublesome task. I have seen women who have had the skin worn off the tops of their fingers in this employment. Sometimes, however, they are rewarded by finding pieces of gold, which they call

sanoo birro

, ‘gold stones,’ that amply repay them for their trouble. A woman and her daughter, inhabitants of Kamalia, found in one day two pieces of this kind; one of five drachms, and the other of three drachms weight. But the most certain and profitable mode of washing is practised in the height of the dry season by digging a deep pit, like a draw-well, near some hill which has previously been discovered to contain gold. The pit is dug with small spades or corn hoes, and the earth is drawn up in large calabashes. As the Negroes dig through the different strata of clay or sand, a calabash or two of each is washed, by way of experiment; and in this manner the labourers proceed, until they come to a stratum containing gold, or until they are obstructed by rocks or inundated by water. In general, when they come to a stratum of fine reddish sand, with small black specks therein, they find gold in some proportion or other, and send up large calabashes full of the sand, for the women to wash; for though the pit is dug by the men, the gold is always washed by the women, who are accustomed from their infancy to a similar operation, in separating the husks of corn from the meal.

As I never descended into any of these pits, I cannot say in what manner they are worked under ground. Indeed, the situation in which I was placed, made it necessary for me to be cautious not to incur the suspicion of the natives, by examining too far into the riches of their country; but the manner of separating the gold from the sand is very simple, and is frequently performed by the women in the middle of the town; for when the searchers return from the valleys in the evening, they commonly bring with them each a calabash or two of sand, to be washed by such of the females as remain at home.

The operation is simply as follows: a portion of sand or clay (for gold is sometimes found in a brown coloured clay), is put into a large calabash, and mixed with a sufficient quantity of water. The woman whose office it is, then shakes the calabash in such a manner as to mix the sand and water together, and give the whole a rotatory motion, at first gently, but afterwards more quick, until a small portion of sand and water, at every revolution, flies over the brim of the calabash. The sand thus separated is only the coarsest particles, mixed with a little muddy water. After the operation has been continued for some time, the sand is allowed to subside, and the water poured off; a portion of coarse sand, which is now uppermost in the calabash, is removed by the hand, and fresh water being added, the operation is repeated until the water comes off almost pure. The woman now takes a second calabash, and shakes the sand and water gently from the one to the other, reserving that portion of sand which is next the bottom of the calabash, and which is most likely to contain the gold. This small quantity is mixed with some pure water, and being moved about in the calabash, is carefully examined. If a few particles of gold are picked out, the contents of the other calabash are examined in the same manner; but, in general, the party is well contented if she can obtain three or four grains from the contents of both calabashes. Some women, however, by long practice, become so well acquainted with the nature of the sand, and the mode of washing it, that they will collect gold where others cannot find a single particle. The gold dust is kept in quills, stopped up with cotton; and the washers are fond of displaying a number of these quills in their hair. Generally speaking, if a person uses common diligence in a proper soil, it is supposed that as much gold may be collected by him in the course of the dry season as is equal to the value of two slaves. Thus simple is the process by which the Negroes obtain gold in Manding; and it is evident from this account, that the country contains a considerable portion of this precious metal, for many of the smaller particles must necessarily escape the observation of the naked eye; and as the natives generally search the sands of streams at a considerable distance from the hills, and consequently far removed from the mines where the gold was originally produced, the labourers are sometimes but ill paid for their trouble. Minute particles only of this heavy metal can be carried by the current to any considerable distance; the larger must remain deposited near the original source from whence they came. Were the gold-bearing streams to be traced to their fountains, and the hills from whence they spring properly examined, the sand in which the gold is there deposited would no doubt be found to contain particles of a much larger size,

*

and even the small grains might be collected to considerable advantage by the use of quicksilver, and other

improvements

, with which the natives are at present unacquainted.

Part of this gold is converted into ornaments for the women; but, in general, these ornaments are more to be admired for their weight than their workmanship. They are massy and inconvenient, particularly the ear-rings, which are commonly so heavy as to pull down and lacerate the lobe of the ear; to avoid which they are supported by a thong of red leather, which passes over the crown of the head from one ear to the other. The necklace displays greater fancy: and the proper arrangement of the different beads and plates of gold is the great criterion of taste and elegance. When a lady of consequence is in full dress, her gold ornaments may be worth altogether from fifty to eighty pounds sterling.

A small quantity of gold is likewise employed by the Slatees, in defraying the expenses of their journeys to and from the coast; but by far the greater proportion is annually carried away by the Moors in exchange for salt and other merchandise. During my stay at Kamalia, the gold collected by the different traders at that place, for salt alone, was nearly equal to one hundred and ninety-eight pounds sterling; and as Kamalia is but a small town, and not much resorted to by the trading Moors, this quantity must have borne a very small proportion to the gold collected at Kancaba, Kancaree, and some other large towns. The value of salt in this part of Africa is very great. One slab, about two feet and a half in length, fourteen inches in breadth, and two inches in thickness, will sometimes sell for about two pounds ten shillings sterling, and from one pound fifteen shillings to two pounds may be considered as the common price. Four of these slabs are considered as a load for an ass, and six for a bullock. The value of European merchandise in Manding varies very much, according to the supply from the coast, or the dread of war in the country; but the return for such articles is commonly made in slaves. The price of a prime slave when I was at Kamalia, was from

nine

to

twelve

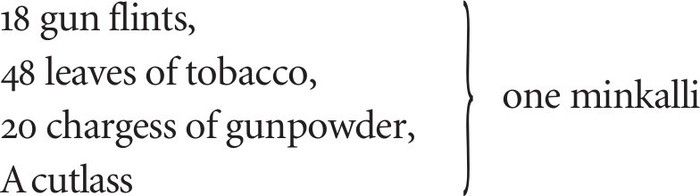

minkallis, and European commodities had then nearly the following value:

A musket from three to four minkallis.

The produce of the country, and the different necessaries of life, when exchanged for gold, sold as follows: common provisions for one day, the weight of one teeleekissi (a black bean, six of which make the weight of one minkalli) – a chicken, one teelee-kissi – a sheep, three teelee-kissi – a bullock, one minkalli – a horse, from ten to seventeen minkallis.

The Negroes weigh the gold in small balances, which they always carry about them. They make no difference in point of value, between gold dust and wrought gold. In bartering one article for another, the person who receives the gold, always weighs it with his own teelee-kissi. These beans are sometimes fraudulently soaked in Shea-butter, to make them heavy; and I once saw a pebble ground exactly into the form of one of them; but such practices are not very common.

Having now related the substance of what occurs to my recollection concerning the African mode of obtaining gold from the earth, and its value in barter, I proceed to the next article, of which I proposed to treat, namely

ivory

.

Nothing creates a greater surprise among the Negroes on the sea coast, than the eagerness displayed by the European traders to procure elephants’ teeth; it being exceedingly difficult to make them comprehend to what use it is applied. Although they are shown knives with ivory hafts, combs, and toys of the same material, and are convinced that the ivory thus manufactured was originally parts of a tooth, they are not satisfied. They suspect that this commodity is more frequently converted in Europe to purposes of far greater importance; the true nature of which is studiously concealed from them, lest the price of ivory should be enhanced. They cannot, they say, easily persuade themselves, that ships would be built, and voyages undertaken, to procure an article which had no other value than that of furnishing handles to knives, etc, when pieces of wood would answer the purpose equally well.

Elephants are very numerous in the interior of Africa, but they appear to be a distinct species from those found in Asia. Blumenbach, in his figures of objects of natural history, has given good drawings of a grinder of each; and the variation is evident. M. Cuvier also has given in the

Magazin Encyclopedique

, a clear account of the difference between them. As I never examined the Asiatic elephant, I have chosen rather to refer to those writers, than advance this as an opinion of my own. It has been said that the African elephant is of a less docile nature than the Asiatic, and incapable of being tamed. The Negroes certainly do not at present tame them; but when we consider that the Carthaginians had always tame elephants in their armies, and actually transported some of them to Italy in the course of the Punic wars, it seems more likely that they should have possessed the art of taming their own elephants, than have submitted to the expense of bringing such vast animals from Asia. Perhaps the barbarous practice of hunting the African elephants for the sake of their teeth, has rendered them more intractable and savage than they were found to be in former times.