Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (15 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

Members of the

Lumpenkommando

, Hershl most likely among them, are directed to the women’s barracks to collect the discarded clothes. The garments are gruesomely warm from the heat of the victims’ bodies. In the yard, other prisoners push baby carriages back and forth between the bundles and the storerooms, transporting bottles, containers and other small objects. The children and the mothers who once used these carriages are already murdered – perhaps just moments earlier. ‘They arrived and were dead within two hours,’ Stangl tells interviewer Gitta Sereny in 1971.

Meanwhile, all birth certificates, education diplomas, letters, as well as photographs must be taken to the Lazarett and burned in the pit. Every trace of those who are murdered must be blotted out. This is now Hershl’s task.

The collection and sorting of pictures is … strictly controlled. For the crime of taking a picture to keep, a Jew was punished by death. Mass shootings took place simply because one of the Jews had hidden on his person a picture of his wife or his near relatives.

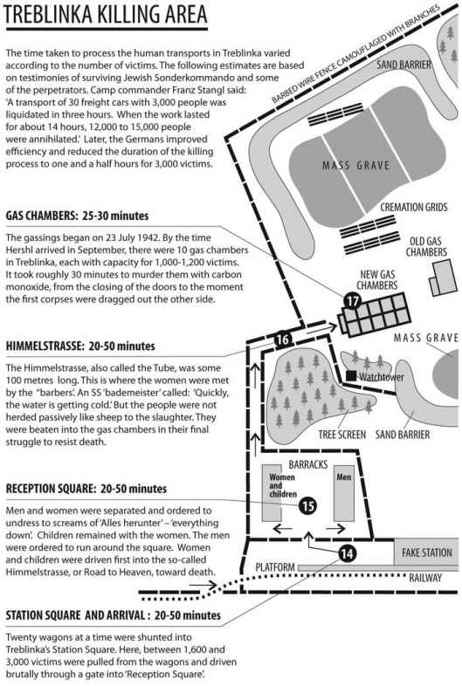

There is no respite. Weeks later, trains from western Europe begin to arrive. One such transport, Hershl tells us, consists of either ‘German or Czech Jews’, and it requires a different strategy. Instead of the controlled hysteria and violence, they are ‘received with all kinds of tricks and pretences which masked the true situation’.

The Germans go to extraordinary lengths to deceive these Jews, perhaps because they are better educated and it is feared they will more quickly grasp the monstrous reality of Treblinka and resist. In his testimony, Hershl identifies SS sergeant Josef Hirtreiter – known as ‘Sepp’ to both the Jews and the Germans – for his particular cruelty.

These people were not beaten on arrival and even the commands were given in a polite and friendly fashion. One woman who has brought a lot of suitcases with her and does not want to go into the Lazarett, is given assurances that her luggage will be sent on after her. She, however, won’t hear of it. All her life, she says, she has worked for the things she has brought with her and she isn’t going to entrust them to anyone else.

Unterscharführer

Sepp finally loses patience with her and cannot resist using his whip. Then she leaves her suitcases and goes weeping and wailing to the Lazarett with the man from the red brigade …

Unterscharführe

r Sepp… had the habit of choosing small children from the newly arrived transports, and skilfully splitting their little heads with a spade.

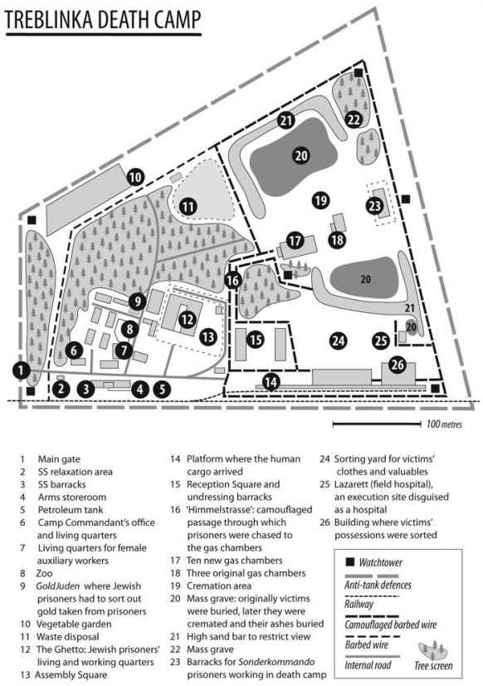

The mass exterminations in Treblinka take place in a section called the upper camp, the Totenlager, or Camp II. This is the murderous heart of Treblinka, isolated from the main camp by camouflage fencing. Stangl has recently installed ten new gas chambers, replacing the original three, increasing the killing capacity from 600 to 3,800 at a time. The height of the new rooms is some two feet lower than previously. The change in dimension is deemed necessary because incidents have occurred where children have not been asphyxiated as the gas rose to the ceiling. Showerheads and pipes criss-cross above the prisoners. The new design maintains the illusion of a shower room. An ante-room contains the engine – appropriated from an abandoned Soviet tank – that pumps the poisonous carbon monoxide through pipes into the chambers. Hershl writes:

It was strictly forbidden to cross from one camp to the other. In the early period, the food carriers used to come to us from Camp II and bring us all the minutest details of the cruel deeds that were being perpetrated there. When we heard about them, we choked and our heads whirled feverishly. It often took hours before we could start working again. The tears running down our faces did not alleviate our helpless rage and our searing pain.

The work of the death camp

Sonderkommando

in the Totenlager – whose ranks vary between 150 and 350, depending on the number of transports – is gruelling, both physically and emotionally. Recruitment for the extermination area takes place in the lower camp – never directly from the transports and often as punishment. Those sent to the extermination area never return.

The food-carriers describe to us how the path to the death camp goes through a garden. Just before you come to the death-shower there is a hut, where everyone is instructed once again to relinquish money and gold. This is always accompanied by the threat of punishment by death. The greed of the Nazis is such that they won’t let even the smallest item of any value slip through their hands.

Now the victims are beaten viciously as they are driven from the undressing barracks in Camp I and through

Himmelstrasse

. The people run naked with their hands in the air. High green walls of pine branches and barbed wire rise up two-and-a-half metres at the sides. An SS man, the

bademeister

, calls: ‘Quickly, the water is getting cold.’ The

Himmelstrasse

bends sharply to the right, so no one entering the tube can see what is occurring at the exit. These people are not herded passively like sheep to their slaughter, as is the perception of many. They are beaten, kicked, punched, and hacked into the gas chambers in their final struggle to resist death.

At the shower room of death, which is adorned only by a Star of David, the victims are received with bayonets. They are driven into the shower rooms, prodded with these bayonets. Whereas the men go into the showers in a fairly restrained fashion, terrible scenes take place among the women. Showing no mercy, the only way the SS can think of to quieten the women is with their rifle-butts or bayonets.

It is here that two Ukrainian guards meet the victims. One of them is Ivan Demaniuk, nicknamed ‘Ivan the Terrible’; the other is his fellow executioner Nikolaj Marchenko. It is a series of trials in the late 1980s in the US and Jerusalem of a man accused of being Ivan the Terrible that will later bring Treblinka to the world’s attention. With a long sword, Demaniuk amputates hands, slices bodies, cuts off women’s breasts. Specially trained dogs are also at the doors, and they bite chunks from victims’ flesh, driving them toward the apparent safety of the shower room. Demaniuk is peculiarly sadistic towards the women. Many witnesses have testified to his cruelty. Hershl will never forget him.

Inside the gas chambers, the walls are covered with white tiles. There is no light once the doors are closed. People desperately struggle against death. None live to tell of the experience.

When all the wretched victims have been forced into the showers, the doors are hermetically sealed. After a few seconds, horrifying screams are heard through the walls. These screams go up to heaven, demanding revenge. The screaming becomes weaker and weaker, finally dying away. At last everything is silent. Then the doors are opened, and the corpses are thrown into huge mass graves, which hold about sixty thousand to seventy thousand people.

Sometime in the middle of November the Germans begin to burn the bodies.

They would dig out a deep trench, and throw in a few old trunks, boxes, wood and things like that. All that is set alight, and a layer of corpses is thrown on to it, then more branches, and more corpses, and so on.

One witness, Jankiel Wiernik, a member of the totenlager’s

Sonderkommando

, tells grotesquely of how the bellies of dead women who had been pregnant, ‘would burst open. The foetus would be exposed and could be seen burning inside the mother’s womb.’ I asked myself in my notepad, ‘How can any man survive Treblinka intact?’ I scribbled beneath that question, ‘Impossible.’

* * *

At 6.00pm whistles blow from every direction, signalling the end of the work day in the lower camp. But the terror and the murder are not yet over. Evening is the most dangerous time for the prisoners, because the punishments are always doled out during the late roll call. Infringements might include possession of food or money, or not working quickly enough or with appropriate zeal. Those deemed guilty are given between 25 and 50 lashes with a special strap made in the camp by the Jewish saddle makers. The victims are placed on a specially designed bench with their bare buttocks exposed. They must count the number of whiplashes aloud, and if there is an error the ordeal is repeated. The sadist Kurt Franz is the camp’s whipping expert and also the designer of the special bench. He conducts the roll-call punishments with a pleasure that has been recorded by numerous witnesses.

I can still see before me the punishment that was meted out to a nineteen-year-old boy who had forgotten to remove the Star of David from one garment. He is shot dead on the

Appellplatz

before the eyes of the assembled work-squads. He is forced to look directly into the gun-barrel. For making a movement of his head when the final command is given, he gets two brutal blows to the face. A few seconds later he falls to the ground, his head shattered, and is quickly removed.

Roll call often lasts several hours. After attendance is taken and the punishments are carried out, Küttner or Kurt Franz conduct what they like to call ‘sports’. Prisoners are made to run in circles and on command they must drop to the ground and then jump to their feet, all while SS and Ukrainians lash with their whips. This ordeal proceeds until the weakest of the Jewish

Sonderkommando

has collapsed. They are then taken by Miete, the Angel of Death, to the Lazarett, and murdered. Any prisoner who has been bloodied or marked belongs to Miete.

The Germans’ entertainment continues.

In the evening, when we are dead tired, we have to sing various songs to the accompaniment of an orchestra. First the Treblinka March, then a Polish song which tells of a mother who sells her child in order not to die of hunger.

Late at night, those who still believe in God pray. Witnesses will recall how each night, Zev Kurland, the Lazarett kapo, recites the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, for those he has seen murdered that day. Others find comfort in writing. Some write and also read aloud their poetry. Others pen descriptions of the horror they witness. Kurland, whose task is to help the victims undress in the Lazarett, is known to have recorded his tragic experiences and often reads them aloud to other prisoners. None of these works have been discovered. Other prisoners select themselves, hanging themselves in the middle of the night. Hershl writes: ‘We often envied those who had it all behind them.’

CHAPTER TWELVE

It was early spring in Scotland. I was at my desk trying desperately to imagine Hershl in Treblinka, when I came upon some bizarre facts about the camp. I looked out of my window and the rain came down in grey sheets. I began thinking how strange Scotland must have seemed to Hershl, but I ended up realising that everywhere – and everything – must have been strange, because Treblinka had infected him, so it didn’t much matter where he was. I called Sam to tell him what I had discovered.

‘You wouldn’t believe some of this stuff,’ I said. ‘I can hardly believe it myself, and I’m sitting here reading it as a historical record.’

‘Go on,’ said Sam, exhaling smoke from another cigarette.

‘Well,’ I began. ‘I know it’s hard to imagine anything crazier than murdering a million people. But while all that was going on, there were other crazy things happening. I mean, if we think of Nazi Europe as an evil kingdom, then Treblinka was a separate little principality of evil – connected but autonomous. It was part of Nazi Europe but it was also its own universe.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Aside from the big fact that Treblinka was a killing centre, there were other things about the place that were simply insane,’ I said.

‘Go on, then, tell me.’

‘Well, for example, in no other place did off-duty killers relax, bizarrely, at their own zoo in the middle of the camp. There is something terribly shocking about these men, given all their murderous brutality and the suffering they caused, being off-duty there, relaxing. The SS men could look at captive foxes and exotic birds, and they had a beer garden with tables and sunshades. But at the same time, just yards away, thousands of victims were driven with whips into the gas chambers. It’s such an ugly paradox.’

‘I see what you’re saying.’

I could not stop myself. ‘The stench of the gas and all that rotting flesh must have been overwhelming.’ I heard Sam groan to himself when I spoke of the rotting flesh, but continued, ‘I suppose they were accustomed to it. That’s strange in itself, don’t you think? Where does this kind of madness fit in the scheme of human behaviour? I admit, I don’t understand. Is it power, boredom, escapism? What is it?’ Sam thought for a long time in the pregnant silence.

‘I think it was a way for the Nazis to fool themselves. It was the same thing with their camp orchestras. They could tell themselves they weren’t really so inhuman if they still had high culture and zoos and beer gardens.’

‘You think it was a way for them to deal with their own barbarism?’ I asked.

‘That’s exactly it,’ said Sam.

I knew that the ten-man Treblinka orchestra had a dual purpose. They performed in the evenings for the SS’s entertainment and during the late roll call while the

Sonderkommando

were being punished. During the day, the musicians played beside the gas chambers in an attempt to drown out the screams of those being asphyxiated.

I opened a copy of Gitta Sereny’s

Into That Darkness

, which was based on her interviews with Treblinka commander Franz Stangl, and I read to Sam what he had said about the zoo. Sereny quoted him: ‘We had any number of marvellous birds there, and benches and flowers. An expert from Vienna designed it for us. Of course, we were able to have experts for anything.’

‘All of the experts were Jews, the vast majority of whom were later murdered. Stangl, oddly, also expressed the view that the camp “became really beautiful”, with its flowerbeds and colourful paint schemes,’ I said. ‘Here was the man who controlled the most efficient killing machine in history, and he speaks about flowerbeds and experts – most of whom he ended up murdering – from Vienna.’

‘Ah-ha,’ said Sam, quickly. ‘Vienna, you see, the place of high culture, experts. The fact they ended up murdering these experts is like the story of Jesus. They murder the Jew and then praise him. It’s the story of Christianity in Europe. This supposed high culture was used to distract their minds from the raw animals that lay at their core. I despise their high culture, and my father did, too.’

‘I’m not sure that it’s the culture that is to blame,’ I said. ‘Isn’t it just a question of perspective? Music didn’t murder anyone. It was the Nazis who murdered people.’

‘No,’ he said. There was now anger in his tone. ‘I still distrust Europeans bleating about culture. They pick and choose at will – they want us to associate Mozart and fine cuisine with their tradition and yet they still cannot face the more essential aspects of their culture – the two-thousand-year-old pathological hatred of Jews, based on a supposed love of one Jew and a vitriolic revulsion of the rest of us. This is still the way in Europe when it comes to feelings about Israel – the Israel-hating left-wing offspring of right-wing European Jew-haters. Most of them are so infected that they don’t even understand. Thousands of years will pass and they will never get it.’

I knew that he was right. It wasn’t just the zoo. I understood this now. There was something pathological at play here. In Treblinka, SS men jogged through nature trails and swam in the Bug River, while a giant excavator dug pits for corpses pulled from the death chambers. Later, the excavator was used to exhume the corpses. A gruesome photograph held in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC shows the mangled bodies of Jews hanging from the digger’s claws. Yet at the same time, just yards away, off-duty Nazis laughed and sipped beer in a zoo.

However, this pathological denial of the terrible, grotesque reality of mass murder did not end with the zoo and the beer garden. By the spring of 1943, flowers and plant pots had been placed outside the Ukrainian barracks – by then called the Max Bialas Barracks. The new guardhouse at the northwest corner of camp was constructed to look like a Tyrolean chalet. A fake but quaint-looking railway station was built by the offloading ramp where the victims disembarked. It was in fact the old storehouse for the belongings of those who had been murdered. A painted clock with numerals permanently reading six o’clock adorned its facade. Hershl tells us, in a tone of utter incredulity, about a fake ticket window, bogus timetables, signposts and arrows indicating ‘toilet’ and train connections ‘To Warsaw’, ‘To Wolkowice’ and ‘To Bialystok’. All of it was designed to deceive Treblinka’s victims and make the job of cramming them into the gas chambers that much easier.

At the end of the

Himmelstrasse

stood an entrance with columns, constructed to look like an ancient classical temple. Five steps decorated with baskets of flowers led to a doorway, covered with a large curtain stolen from a synagogue, masking the gruesome reality of the place. Above the portal, a Star of David was mockingly engraved and the Hebrew words inscribed: ‘Through this gate only the righteous pass.’ In the margin of the Treblinka history book, in which I again re-read this information, I scribbled the inadequate word, ‘Spite’.

Spite, I suspected, also played its part in the relationship of the SS with each other. Greed and robbery perhaps made them feel they were something other than murderers and barbarians. Yet, economic plunder was always part of the plan at Treblinka.

When each order for clothes comes in, the carefully sorted and packed stolen clothes are sent away. Usually a whole transport will depart with one article. There goes, for instance, a transport consisting entirely of suits, another consisting entirely of women’s silk dresses, a third of shoes, and so forth. Gold is loaded on to lorries and taken away separately.

A letter from Globocnik to Himmler in 1944 reported the value of goods and cash taken from those killed in Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor – the three Operation Reinhard camps – at around $75 million (worth $1.2 billion in 2009). But not all that was plundered ended up in designated Reich accounts.

Treblinka was the centre of an enormous black market. The Ukrainian guards, SS, and the local population all reaped rich rewards from the murder of Jews. The economics of supply and demand ran riot. Ukrainian guards pilfered food and sold it at hyperinflated prices to prisoners, who themselves maintained illicit hoards of currency, gold and diamonds – in spite of certain death if discovered. Among the testimonies from SS men and prisoners regarding the trade between the Ukrainians and the local population, there are stories of prisoners paying the equivalent of hundreds of US dollars for packages containing bread, sausage and vodka. At the same time, the price of material goods deflated because of the enormous supply. Men’s watches sold for pennies. Farmers were seen with dozens of them in egg baskets, offering them for sale on market days in the local villages. Expensive fur coats were a common sight among village women. Some black marketeers arrived in the forests surrounding Treblinka with truckloads of vodka and bread to exchange for valuables they would then sell for hundreds of times their purchase price in Warsaw.

Between 3 September 1942 and mid-February 1943, some 438,600 men, women and children were brought from the General Government of Occupied Poland and a further 110,000 from the Bialystok district in the north-east were deported and then killed. A single person from one transport of 5,000 Jews might be selected for work; maybe two or three from another. In October 1942, some 6,800 Jews from the town of Zarki, the home of the kibbutz training camp, not far from Częstochowa, were deported to Treblinka. Population records reveal numerous Szperlings in the town and at the kibbutz-training village, who had intended to make their home in Israel. Many had come from Klobuck. Hershl watched them driven naked to their deaths. He, too, had intended to prepare for kibbutz life at Zarki when he was old enough. ‘New transports arrive at Treblinka all the time. Sometimes there is a break of a few days. But on average ten thousand people per day are murdered in Treblinka.’

The possessions of those people ended up in the sorting yard, piled into mountains, and in the sorting barracks, organised for shipment, where the SS and Ukrainians dipped into piles of ladies’ underwear, men’s coats, and babies’ clothing, like customers at a vast outdoor market, to pull out something for their wives, friends or children.

The SS units become enormously rich. As compensation for the gruesome work in the camp, they are granted four weeks’ leave and always travel dressed in civilian clothes. Each time, they take with them about ten suitcases. They take the best and most expensive clothes and the most beautiful gold and diamond jewellery for their families.

Sometimes, the clothing sorters were instructed to keep a look-out for a nice fur coat, and a pack of cigarettes was thrown down in payment. Deals were struck that very quickly became choices between life and death. At other times, depending on the SS officer, requests for certain items of clothing came simply as a command. Workers sometimes slashed fur coats as they were sorted, flawing the garment in a small act of resistance.

At the same time, just as bizarrely, the prisoners were able to dress and eat like barons. Many of them ate better in Treblinka than in two years in the ghetto. Each transport of victims brought with it hundreds of food packages containing meat, potatoes, bread, jam, butter, and jars of protein-rich egg barley, all undoubtedly prepared by a concerned wife or mother. Good-quality clothes and sturdy boots were also plentiful. The many Jews who believed they were being ‘sent for agricultural work in the east’ came prepared.