Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (6 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

Rebecca Bernstein, an old woman in Canada with whom I had been in contact before coming, told me during a telephone conversation a few weeks earlier how as a child she had lived next door to the Szperlings in one of two large buildings in the shtetl. She also remembered Gitel Szperling as a ‘very tall and distinguished woman’; but she did not want to discuss Hershl. The Yizkor book of Klobuck records twenty Szperlings as household family heads in the town. Nearly all of them perished. Most of the Szperlings throughout the world today are the descendants of those who left Klobuck for Israel before the war. They had been part of the Hashomer Hatzair training kibbutz at Zarki, close to the city of Częstochowa, and attendance at the centre was a source of pride for many Jews in southern Poland. Surviving records list numerous Szperlings at Hashomer Hatzair, the purpose of which was to prepare Jewish youth for life in Israel. Emigration to Israel was the aspiration of almost every young Jewish man and woman in Klobuck, and Hershl was no exception. His plans to train at Zarki and make a pioneer’s life in Israel were soon to be obliterated by the German onslaught.

Life for Klobuck’s Jews changed drastically after Pilsudski’s death in 1935. In the political battle to fill the power vacuum, a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms washed across the country, encouraged by Poland’s new nationalist government amid an economic depression and the alarming events that were unfolding in Germany. Violent gangs called Endeks, supporters of the right-wing, pro-Catholic, anti-Semitic National Democrat Party, attacked Jews throughout Poland. Klobuck was not spared; abuse of Jewish children in schools became commonplace in the town. Polish high-school students, influenced by the Endeks, forced Jewish students to stand during Catholic religious lessons. The teachers, even those who were not anti-Semites, were often afraid to intervene. Years later, Hershl recalled the childhood terror and humiliation of attending the school in Klobuck. Bullies lay in wait for Jewish children with rocks in their hands. In the classroom, only Polish children were permitted to occupy the first rows of seats; the back was reserved for Jews.

Sundays were particularly violent, as were Catholic festivals. Endeks gathered outside the church on Jewish holidays and rampaged through the streets of the shtetl, shattering windows and stoning Jews. A passage in the Yizkor book tells of Klobuck’s Endek leader, a lame man named Meyer, who was an employee at the Jewish-owned mill. The Jewish community ended up bribing him to leave the town, which he did, but he returned when the Nazis arrived and became a collaborator. Then, turning the screw tighter, the nationalists declared an economic boycott of Jewish goods. Pickets were stationed at Jewish shops and at traders’ stalls on market days. The shtetl economy was in collapse and poverty was the norm.

My head began to spin; I realised I was hungry. It was already 4.00pm, and I had eaten almost nothing since breakfast. I walked across the square and into a restaurant, on what had been the Christian-Polish side of town. I sat down and ordered a pizza – all that was on the menu – and a beer. I was served by a teenage boy with good English. He told me how every summer the young people of the town would swim in a small, nearby river. It was the river where Hershl had learned to swim, and I thought about him floating face down in the River Clyde in faraway Scotland. The teenager told me his ambition was to travel in America. He said he wanted to meet people of different nationalities and different faiths, and I thought that there was hope for this town, this country. It also felt better to be off my feet, and my head began to clear with the first bite of warm food. But something was out of place in my mind, and I decided to call Rebecca Bernstein in Canada. It was morning in Winnipeg and she would surely be awake by now.

‘Rebecca,’ I said, ‘I’m in Klobuck.’

‘You’re in Klobutsk?’ she asked, using the Yiddish name for the town.

‘Yes, I’m in Klobutsk.’

‘You’re crazy,’ she said.

‘Maybe,’ I said. ‘Rebecca, I need to know something about Hershl in Klobuck. I need to know what it was like to live next door to him when he was a child. I also need to know what happened here, and what happened to Hershl.’

I could hear her breathing and gathering herself to speak. At last, she said: ‘I used to call him Hershele. It was a special name for the nicest and kindest little boy you could imagine. I was eleven and I think he was a year older. I really loved him you know, but there was another girl that lived across the street he liked better than me. But we were all friends, all the children from that corner of the shtetl, and we all used to swim together and play together. It was a wonderful time. Then the Germans came and everything changed.’

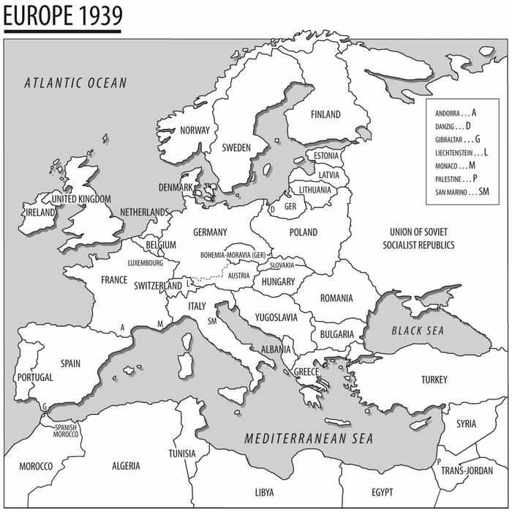

By 1939, the map of Europe was already changing as a consequence of German opportunism and aggression. In 1936, Hitler moved troops unopposed into the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland, directly contravening the Treaty of Versailles. Neither France nor Britain took action against him. Although the Rhineland had been intended as a buffer zone between France and Germany, the French were clearly unwilling to fight for it. Emboldened, Hitler now turned his gaze east.

In 1938, the dictator annexed Austria, whose prime minister was soon assassinated. That same year, the Munich Conference gave Hitler Sudetenland, under the pretext of alleged privations suffered by ethnic Germans. The region now became the new protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia, and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared: “We have peace in our time.” The remainder of Czechoslovakia, powerless to resist, fell to Germany on 21 September, 1938.

Less than one year later, on 1 September, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and the Second World War began.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said.

‘It’s not your fault,’ she snapped. ‘The Jews from Klobuck, those of us who survived, we all used to meet every year in Florida. Every year, I used to ask about Hershele, if he was here, what happened to him. We’d heard that he survived, but we didn’t know where he was. Every year, I used to look for him, hoping that one time he would come, but he didn’t.’

She asked if Hershl had grandchildren. I had to tell her Hershl’s two sons were also haunted by the terror of the Holocaust. ‘You never know, but I don’t think there will be any grandchildren. I can’t speak for them, but I don’t think either of them want to bring children into a world where they will suffer like they did.’

‘That’s the real tragedy. I have a beautiful grandson, who is already 28. But Hershele was in Treblinka. That explains it. All those people went there to die and he had to watch it. My parents died in Treblinka, but I was taken to a work camp near Klobuck, and I survived. My parents ran away from the ghetto in Klobuck to Częstochowa, where we had relatives. But then the Częstochowa ghetto was liquidated. I haven’t even got any pictures. I’m 80 now and I can’t remember my mother’s face anymore. But I do remember my little Hershele. He was such a wonderful little boy, always so kind. I could never forget him.’

* * *

In 1939, Klobuck lay just twelve miles from Germany. Hitler’s rise to power, nourished by his racial ideology, focused at first on the country’s deep sense of humiliation after its defeat in World War I and lingering resentment over the loss of the former German territories of Prussia and the city of Danzig. The Jews were blamed, in typically brutal language, for everything from the defeat in 1918 and the subsequent economic hardship, to rising inflation and even prostitution. Hitler demanded that the German people take up the ‘harsh racial struggle’ against the Jews. Germany could only become great again if the Jewish people were removed. But he did not just mean the Jews in Germany. His plans called for the annihilation of Jews everywhere. By attacking Poland, he could stake his claim to Prussia and at the same time launch a massive strike in a secondary war against the Jews in their largest community in Europe.

It began bizarrely, late in the evening of 31 August 1939, in the German border town of Gleiwitz, some 80 miles south of Klobuck. A small group of German operatives entered the town and, at gunpoint, seized control of the local radio station. They proceeded to broadcast in Polish a message urging the residents of Gleiwitz to rise up against Germany.

As part of the ruse, they brought along an ethnic German named Franciszek Honiok, who had been arrested the previous day as a Polish sympathiser, and murdered him with a lethal injection. Then they dumped his body outside the station and fired gunshots into it to make it look as though Honiok had been killed during an attempt to overrun the station. The idea was to make Germany look like a victim of Polish aggression. Honiok’s was the first death of World War II.

The fact that he had been killed by lethal injection was ominous. The order for the Gleiwitz attack came from Reinhard Heydrich, head of the

Sicherheitsdienst

, or SD, the Reich’s intelligence service. Heydrich had taken a special interest in the Nazi’s euthanasia program. The headquarters were at Tiergartenstrasse 4, in Berlin, thus the codename T4. Under this initiative, some 80,000–100,000 Germans – physically and mentally disabled children and adults – were secretly killed by lethal injections or in gassing installations designed to look like showers. It was a vile foretaste of what was to come. Less than two years later, Heydrich would present the plans for the gassing of almost two million Jews in the death camps of Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka. That murderous scheme was later named Operation Reinhard in Heydrich’s honour. Hershl had called them ‘Reinhard’s camps’.

At exactly 4.00am the following day, the German battleship

Schleswig-Holstein

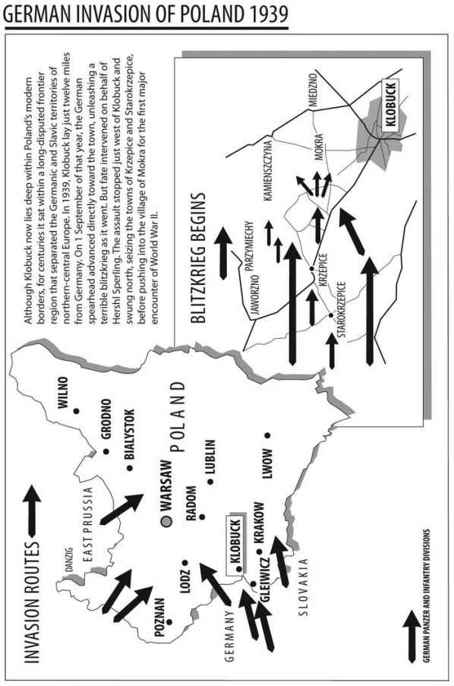

slipped its moorings in Danzig harbour and shelled a Polish transit base on Westerplatt. The war had begun. In the south, Klobuck found itself in the unfortunate strategic position of sitting directly in the path of the German Eighth and Tenth Armies and the Fourth Panzer Division. An hour later, these forces crossed into Polish territory.

News of the advance crackled by radio through the shtetl and the rest of Klobuck. The town went into a panic. Those Jews who had not yet heard about the German invasion were awakened by noisy crowds in the street. Icchak and Gitel Szperling had switched on their wireless early, as was their habit, and a sense of dread descended almost instantly. If they looked from their upstairs window, they saw a steady stream of citizens fleeing eastward out of the town. Against the advice of his wife, Icchak went out to make ready their horse and cart. Gitel woke Hershl and he in turn would have been instructed to wake Frumet. He was twelve and his sister was six. They dressed quickly and he helped her gather a few belongings. If Hershl looked from the window, he would have seen men from the Polish National Guard breaking into Jewish homes and shops, and looting them. It was not yet 8.00am, and some of the soldiers were already lying drunk in the gutter with their long French rifles at their sides. It was clear there would be little resistance to the Germans, at least in Klobuck. Icchak now returned. Their horse and wagon had already been stolen. They would have to flee on foot with the rest of the town. War had broken out, Icchak explained to his children, and because they lived close to the border, everyone in Klobuck would have to leave their homes.

The German spearhead advanced swiftly and directly toward Klobuck, unleashing a terrible blitzkrieg as it went. This was Hitler’s new devastating style of warfare, based on speed, shock and ferocity. It began with the frightening wail of the Stuka dive bombers, fitted with sirens and whistles for additional terror, which struck at rail and road lines without respite, often in the middle of villages, towns and cities. They machine-gunned the fleeing population. Then, wave after wave of tanks and artillery fire pushed forward, pounding everything in their path.

Fate now intervened on behalf of Hershl Sperling, not for the last time. The assault force stopped just west of Klobuck and swung quickly north, seizing the towns of Krzepice and Starokrzepice, before pushing into the village of Mokra. Word came to the German command from the motorcycle reconnaissance squads of the Fourth Panzer Division that Polish strongholds had been sighted near Mokra. And so began the Battle of Mokra, the first major encounter of World War II.

Every Jew in Klobuck, as well as hundreds of Poles, fled east, away from the battle. In the distance, they could see the Stukas dive-bombing Mokra, less than five miles away, and they could hear the wailing sirens and the anti-aircraft fire. As the Szperlings left town with the column of fleeing refugees, a Polish soldier with a torn jacket and a bloodied shoulder passed them on a motorcycle going back to Klobuck. Two Stukas flew above them and dove low, causing alarm among the escaping population, many of whom lay prostrate as the aircraft screamed overhead.

The ten-hour battle, which eventually dissolved into a series of disjointed skirmishes between a 15,000-strong Panzer division and a few Polish cavalry platoons in and around the burning, smoke-filled village of Mokra, ended after two Polish armoured trains arrived and attacked the tanks from behind. Through the confusion of the smoke, the Panzers several times fired on their own positions, instigating a retreat. This rare German defeat lives on today in the Polish national memory with much pride. However, Polish military tacticians decided, because of heavy casualties, to withdraw to a second line of defence. The main purpose of the resistance had been merely to buy time to allow the Polish reserve army to mobilise. Mokra had been defended in vain. The Wehrmacht now readied itself to crash through the defence armies of Lodz and Krakow, cross the Warta River and surround the Polish forces on the western frontier, thus clearing the road to Warsaw. That evening, German tanks pushed into Klobuck, which was now defenceless and almost empty.

Meanwhile, in a field, just ten miles east of their town, 3,000 people stopped exhausted after a full day of walking. Most of them had come from Klobuck, but others had joined the flight en route from nearby villages. There were old and young, Jews and Poles. Only the

Volksdeutsche

, the ethnic Germans who had been settled in Poland generations ago, and the old and infirm stayed behind. It was a Friday night and as twilight descended, the Jews said their Sabbath prayers, Icchak, Gitel, Hershl and Frumet Szperling among them. The Christians also prayed for God to have pity on their children and their town. Then they ate the food they had carried with them and went to sleep beneath the dark sky.

* * *

I found Jerzy, my taxi driver, in a dark underground bar on the opposite side of the square, as planned. He was sitting by the door with a small glass of beer before him, eyeing black-clad waitresses who squeezed between the tiny tables with trays of vodka shots and sandwiches. He waved as I entered. This was obviously the place where Klobuck’s wastrels hung out.

‘We go?’ he asked. ‘Częstochowa?’

Back in the taxi, I asked to look at Jerzy’s map. I studied it and instructed him to drive north, even though Częstochowa lay to the south. I did not mention that it was obvious from the map that he had taken a great arching detour to arrive at Klobuck via Krzepice earlier in the day. I wasn’t angry because it had clearly been made for my benefit and the ruined Krzepice synagogue was obviously a tourist site for visiting Jews. Now I wanted to return for a closer look. Jerzy held up his finger and then carefully wrote the extra charge on a small yellow notepad that was attached to his dashboard beneath the icon of the Madonna. I agreed, and in ten minutes we were back in Krzepice.

The ruined synagogue and a few old, stone-built homes lay a couple of miles beyond the town, close to the banks of the Listwarta River. It seemed a strange place to build what had obviously once been an ornate and elaborate construction, but I supposed the Jews of Krzepice must have lived here on the outskirts of town. The concrete had broken off to reveal the bare red brick, and four columns stood at the entranceway beneath a large semi-circular window and an ornate Star of David carved into a plaster tablet above the doorway. The round paving stones that led to the door must have once made a pretty courtyard in front of the building. The roof had long-since collapsed. It was a tragic sight.

‘Please, wait,’ said Jerzy, in French. ‘I come back.’ He walked over to the row of cottages beside the synagogue and moments later returned with an old man and his small yapping dog. ‘We can go in now,’ he added, introducing the man as Mr Ciesla and saying he was 90 years old. It seemed strange that we had to ask this old Polish man for permission to enter the synagogue. I regarded him with suspicion. We followed him into the ruins of the building. Mr Ciesla spoke in Polish and Jerzy translated into pidgin French. He told me that Jews had lived in Krzepice since the early seventeenth century and that this synagogue had been built some time in the early eighteenth century. His son had studied the town’s history, he told us. The synagogue’s floor was gone. Grass, weeds and earth covered the ground within the walls. I could see the enclave in the far wall where the ark of the Torah had once rested, and rows of arched window frames on either side of it. This had obviously been a magnificent structure before the Nazis came.

I asked Mr Ciesla if he knew what had happened here, and a look of sadness instantly fell across his face. It was hard to tell whether it was affected or genuine. His dog scrambled through the bushes and the tall grass.

‘I was here when it happened,’ he said. ‘I’ve lived in that house next door all my life.’ He spoke matter-of-factly. ‘The Germans rounded up about 100 Jews when they first came here just after dawn in 1939, and forced them all inside the synagogue. Then they sprayed everyone with machine-guns.’ He made the rat-tat-tat sound of machine-gun fire. He continued: ‘Then they locked the door and set fire to the building. Everyone who was alive was screaming. Everyone was killed.’ Then he shrugged, but I could see there was emotion in his eyes. He spoke to Jerzy in Polish.

‘He wants to take us somewhere,’ Jerzy translated. ‘It’s ok, we go.’ We got into his taxi and drove along a dirt track at the side of a muddy field. We stopped at the edge of a small wood and got out, following Mr Ciesla. ‘Come, come,’ Jerzy said, beckoning me. We came to a clearing on the other side of the wood. There, amid the tall, unkempt grass and weeds, stood crooked grave stones, most of them broken and chipped. There were also cast-iron tombstones. The passage of time had rendered most of the Hebrew inscriptions indecipherable, but on one I could read − Yaakov, son of Yitzhak, and the date 5559, the year 1799. I could also see the carvings of candles used for women and the stars of David for men, and another with the motif of a broken branch, signifying a child. These were the lucky ones, I scribbled in my notebook. They had lived and died naturally in their own community, long before the Nazi onslaught.

We dropped Mr Ciesla and his dog back at the cottage. I called, ‘Dziynkuja – thank you’ to him from the car, and he waved his arm without turning back as he headed into his house. Jerzy gunned the engine and took off.

‘Now Częstochowa?’ he asked, clapping his hands together before touching his Madonna and placing them back on the steering wheel.

‘First, back to Klobuck,’ I said. ‘I want to take the east road out of Klobuck. Then Częstochowa.’ He nodded, rubbed his hands together and swung back to Hershl’s village.

I took one last look at Klobuck as we drove around the market square and headed east. We passed through the villages of Lobodno and Ostrowy. It was unlikely that the mass of fleeing refugees would have made it beyond this point. Just past Ostrowy, I asked Jerzy to pull over. It would be twilight soon, and I got out the car and looked across the snow-speckled field. The sky was grey and heavy with broken clouds. It was winter, but I tried to imagine what it was like in this field on that late summer’s morning in 1939. I knew what had happened here from what I had been told by Rebecca Bernstein and her cousin, Rubin Sztajer, the then thirteen-year-old son of the town’s Mikvah keeper.

On Saturday morning, the refugees were still making preparations to continue their flight when a tank appeared behind them. Rubin, who now lives in Baltimore, wrote to me: ‘I had never left home before, and I didn’t know the difference between a Polish soldier and a German soldier. They told us we were liberated. We turned and marched home, but before we reached our village we were stopped, Jews and Christians alike. They immediately separated the Jews from the Christians, who were allowed to go home.’

The Jews were detained and spent another night in an open field. They waited in fear. Few slept. Germans guards surrounded them. Jews with beards and sidelocks bound their faces in cloth to hide their appearance, in the hope they would look as though they had a toothache. A rumour spread through the group that they were going to be shot. Others consoled themselves with the belief that they would be sent to a detention camp. Early the next morning, Sunday 3 September, Britain and France declared war on Germany, but it was of little consequence to the Jews of Klobuck, or anywhere else in Europe for that matter. A German officer addressed the Jewish refugees in the field. They were told they could return to their homes. On that same day, SS chief Heinrich Himmler gave the order for the army to kill anyone it deemed necessary in ‘the combating of all anti-German elements in hostile country’.

The Jews were marched back toward Klobuck. It was now almost nightfall. They had walked for another full day. They were exhausted. I imagined Frumet crying, and Hershl picking her up. About three miles outside of town, the road divided near a small woodland. Hershl and his family, along with Rubin Sztajer, Rebecca Bernstein, and the majority of the Jews of the shtetl took the right fork to their homes. As they moved through the streets, they saw their homes had been looted and burned. No window was left unbroken.