Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (2 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

Train journeys had long punctuated Hershl’s existence. On his journey from the Częstochowa ghetto, in a stinking boxcar, he would have seen familiar station names rolling past – Radomsko, Piotrków, Koluszki. Hours earlier, he had witnessed savage attacks on his neighbours. People were dragged from the ghetto, beaten and shot. As a desperate escapee, a train had taken him away from a village some 40 km from Treblinka to Warsaw. He was one of the few Jews to see the Warsaw ghetto in ruins after the uprising. Another train had taken him from Warsaw to Auschwitz and from Auschwitz to Birkenau and, close to death, from the station at Gleiwitz to concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Dachau, and Kaufering less than a year later. A train took him back to Polish soil after liberation, when life was hopeful again, only to encounter anti-Semitism of such fury among his former neighbours that he fled. While waiting for another train to carry him back to Germany, he met his future wife on a station platform in Czechoslovakia, and together they would take a train to the Hook of Holland, and later he would board a boat alone and another train that would take him to a new life in Scotland. Now he was on his final train journey.

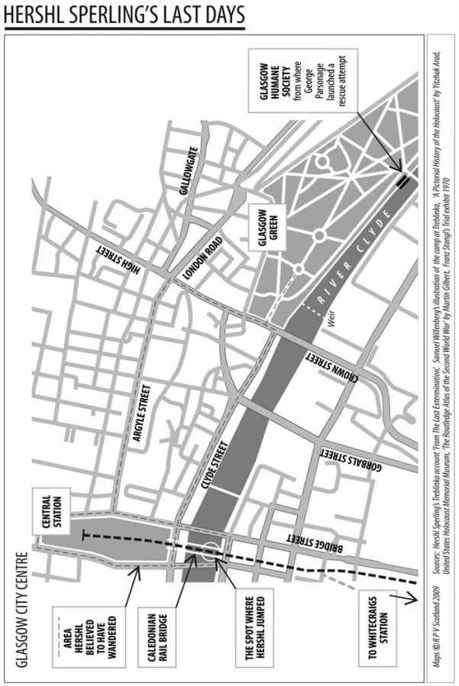

The locomotive pulled into Glasgow Central station. Did he recall the boxcar door sliding open at Treblinka, the blinding light, when the train finally arrived? Did he recall the truncheons and hear the savage cries of ‘

Raus

’? Most likely he exited Glasgow Central by its main entrance on to Gordon Street with the bulk of the crowd, and disappeared into the throng of shoppers and workers. Whether he first wandered the streets of Glasgow or if he went directly to the rail bridge, we do not know. For weeks now, his had become a world of death and phantoms. Certainly at some point he turned south and began to walk toward the river. He crossed the Broomielaw, the street running parallel to the northern bank of the Clyde, traversed one of the pedestrian bridges that span the river and then climbed into the iron rail bridge to spend the night. In limbo between life and death, he listened to the screams of trains as they passed above him.

Today you will find the same paved esplanade and railing. In spite of the attempts to regenerate the city’s riverside areas with upmarket apartments, shiny office blocks and street clean-ups, this south bank of the river has remained dingy. As night falls, the vagrants descend. Hershl’s final nights were spent among the city’s drug addicts, alcoholics, homeless and the mentally ill.

Hershl’s mental health had deteriorated sharply in recent months. In the weeks before, he seemed to slip gradually into the world of the

muselmänner

, a word used in the camps to denote the submerged, those human beings irreversibly beaten to the precipice of death. In the camps,

muselmänner

were those who had resigned themselves to death. The origin of the term remains unknown. One explanation is that these victims were so called because they often had bandages wrapped around their heads and took on the appearance of Muslims. Like Hershl, they no longer spoke. In Treblinka, Auschwitz and Dachau, Hershl had seen these emaciated walking corpses. Often

muselmänner

were clubbed mercilessly to death or they simply dropped from exhaustion. It is possible that Hershl’s unfulfilled need to tell the world of the horror and his own loss had driven him in the end into the condition of a

muselman

.

In spite of the emptiness in his eyes, and the drugs and the whisky in his blood, Hershl’s mind was far from empty. He had plotted to frustrate all attempts to find him, at least long enough for him to do what he had to do. He had come to this point with purpose. He had sought out the company of tramps in the past, and it is possible he knew when and where to come for shelter after dark, where his night-time, half-delirious and pained cries in Yiddish would not be disturbed, or even regarded as out of the ordinary. The day Hershl left home, sunset in Glasgow fell at 7.03pm. In northern Poland, at the site of Treblinka, it was at 7.24pm.

The time before the war was not so far away for Hershl Sperling, except his memories of happier times were painful – the life he had had with his mother and father, his red-haired sister, the town, his house, their animals – all gone now. Hershl had cried for his family, and all those others who were smoke. He had spoken of the shoes and the ashes, the terrible smell of burning bodies and the clothes and the yellow stars. In Treblinka, he had been forced to sort through the clothes of the dead. He was also assigned the job of opening the boxcars and, because of his ability to speak fluent German, Polish and Yiddish, to translate the orders of the SS men. After the victims disembarked, he cleaned the putrid wagons. He removed the bodies of those who had died en route and dragged them to the burning pits. He had spoken of these things as if he were the only one who knew of them, and the only one alive to care about them. There was a small lace-up boot – belonging perhaps to a child of five or six. There was a large man’s shoe, a young woman’s shoe with a high heel, a child’s coat. What had become of those shoes and coats? He could never forget how the bodies had started to rot and stink beneath the earth in the mass graves nor how the Nazis had exhumed them, all the people who had owned those shoes and coats he had been forced to sort. He could not forget the corpses that were cremated on giant iron grills above the pits.

An article in a later edition of the

Glasgow Evening Times

updated the story. Police divers were called in as ‘fears grew for the safety’ of Hershl Sperling. It said police had already conducted extensive searches of Whitecraigs golf course without success, and that the search had been extended to nearby Rouken Glen Park and Deaconsbank Golf Club. The searches in Prestwick and Ayr were also being stepped up and police officers in the two towns had joined the hunt.

We do not know if he left the bridge the following day to wander through the city, or whether he remained. We know that he was there, probably lying across one of the girders, in the middle of the afternoon.

* * *

At 4.00pm, on Wednesday 27 September 1989, George Parsonage, the sole lifeboat officer of the Glasgow Humane Society, received a call from the city’s police. A body had been observed floating in the shallow part of the river, just under the Caledonian Rail Bridge. Mr Parsonage rowed to the scene. ‘I always row to these kinds of incidents,’ said Mr Parsonage, who in four decades has dragged more than 2,000 bodies from the River Clyde, some 1,500 of them alive. I met him at his house on Glasgow Green in the summer of 2007. The river flowed fast over a weir a few yards in front of the house.

‘A motor boat creates waves,’ he said, ‘and maybe, just maybe, there is a pocket of air in a jacket that can keep a person afloat and maybe alive.’ Then his face darkened. ‘I saw him lying face-down on the south side of the river, in about two or three feet of water as I rowed toward him. Men nearly always sink, unlike women. So, for a moment, I thought he might be alive. When I reached him, I turned him over, with his back to the boat, and pulled him on to the gunwales. I had to decide there and then whether to try to resuscitate him with mouth to mouth, but now I could see he was dead.’ I asked him if he could tell how long he had been dead. ‘I’d say maybe half an hour,’ Mr Parsonage replied.

‘I searched his pockets for identification. He was wearing a jacket, which I took off him. It was then I saw the number. I was utterly shocked. I realised that man in the water had been in Auschwitz. To think what he had been through was unimaginable.’ He looked directly at me. I could see his eyes water. ‘He had my respect. And what kind of society are we living in, when we let this happen to a man like this, who had been through what he had? I’ve never forgotten him.’

Mr Parsonage, who possesses an optimism that perhaps can only come with the kind of work he does, added: ‘We cannot be sure it wasn’t an accident. Personally, I don’t believe in suicides. I have yet to encounter a suicide that didn’t cry for help when he hit the water. Therefore, at the moment of death, it is no longer a suicide. It was clear the man had come off the bridge. But if he were lying on one of the girders, it would be easy to fall, either if he was sleeping or drunk. There is a big possibility he was sleeping and fell off the bridge.’

Indeed, Hershl had been drinking, and he was also taking large doses of Valium and Amitriptyline. He could swim – according to his sons he could swim well – but the intoxicants may have rendered him unconscious. I later put Mr Parsonage’s theory to both Hershl’s sons. His younger son, Sam, said: ‘I don’t think he had any intention of coming home again.’ Alan agreed.

The following day, two brief paragraphs reported the conclusion of the police search for Hershl Sperling: ‘The body of a missing Newton Mearns man was today recovered from the Clyde in Glasgow. Henry Sperling, 60 [he was in fact 62], had been missing since last Friday.’

In the end, the survival of Hershl Sperling was no survival at all. He wanted his mind to stop. The suffering that began 47 years earlier had continued for the rest of his life, forcing him each day to relive the punishment that the perpetrators had inflicted upon him.

But this was not the end. In 2005, I discovered Hershl had left behind him a hidden legacy that would reveal the truth about his survival and his death, a story that otherwise would surely have been lost. He had dared to put pen to paper in the months after his liberation, a raw truth in a written record of the things he – and all those who could no longer speak – had witnessed.

CHAPTER TWO

The quest to understand Hershl Sperling’s fate begins with the rediscovery of a secret and long-forgotten book. This was one of his most guarded and valued possessions. He kept it in a brown leather briefcase, which always remained in some out-of-the way cupboard, far from the reach of children or anyone else who might intrude into his world. In this book lay the terrible truth – not just about Hershl himself and what he had been forced to endure, but the truth about all people and what some of us are capable of. The American artist John Marin once wrote: ‘Some men’s singing time is when they are gashing themselves, some when they are gashing others.’

For more than 45 years Hershl kept the book beside him wherever he went, from country to country – and there were many such moves in his life – from home to home and place to place. In spite of the book’s dreadful contents, it comforted him because it was evidence of what had truly occurred, and the truth was all Hershl had to live by. Its contents were as real as the voices of his tortured dreams. If he cried out while napping in the afternoon, his wife would run to his bedside and whisper comforting words in Yiddish. I remember the intensity of her voice as she pleaded with him to come back; he was always disoriented after these bouts. The book, with its pale green cover, the same colour as Hershl’s eyes, held the secret of those nightmares. It was written in Yiddish in Hebrew script, and was published in Germany in 1947, some fifteen months after liberation. No-one inside or outside his family was permitted to look at it and few knew of its existence. Hershl’s wife was among the few to know the book’s contents. I was aware of Hershl’s obsession with the contents of the briefcase, but only because my friend Sam had told me. I knew no more and I dared not ask.

We were a family of Americans in Scotland and we lived around the corner. Hershl liked Americans because they had liberated him in April 1945, as their armies swept through Germany toward Berlin in the final weeks of the war. Our shallow roots in Scotland were on my mother’s side. My great grandmother had been a teenager en route from Riga to New York in the late nineteenth century when the steamer captain hoodwinked her, and a few hundred other Jews, into thinking she had arrived in America. The ship had in fact stopped at the Scottish port of Greenock. It was a common enough ruse among the captains of shipping companies that allowed them to take on more passengers. My great grandmother was a lone Jewish girl from a Latvian farm, and she did not know New York from a piece of apple strudel. My Scottish-born mother, who had emigrated to the US in the 1950s, got homesick some seventeen years later and the family moved back.

Hershl and Yaja Sperling, both of them orphaned by the Holocaust, lived then in their house at 63 Castlehill Drive, Newton Mearns. I remember Yaja as a beautiful and stylish woman in her forties, always impeccably dressed, smiling and kind. Her hair was jet black and her eyes were a deep, dark blue. She worked as a manager at Skincraft, an upmarket leather and suede retailer in the centre of Glasgow. I remember thinking then that was an ironic name for a store for a Holocaust survivor to work in. Even then, I was vaguely aware of macabre atrocities in which the skin of murdered Jews had been fashioned into ornaments. The source of that, although I did not know it, was Ilse Koch, the wife of the commandant of the Buchenwald camp – Ilse is infamous for ordering the manufacture of furniture out of human skin and bones, including skin lampshades. The so-called ‘Bitch of Buchenwald’ committed suicide by hanging herself at Aichach women’s prison in 1967. The Sperlings would not even purchase a throwaway plastic pen if it had been made in Germany.

Yaja Sperling was devoted to her family. She loved her husband profoundly and was enormously proud of her two children. Neighbours remarked that she and Hershl behaved like teenagers in love. They held hands and each evening after their meal they strolled through the neighbourhood arm-in-arm. I remember my father saying, almost every evening at around 7.00pm, as he looked out of the window: ‘There go Yaja and Henry again.’ In their house, when she would put down his lemon tea in a glass after dinner, I remember her smiling at him. It was an intimate moment. She never tired of caring for him. Yaja was Hershl’s anchor, and I remember they loved each other with a painful tenderness and a secret passion.

She was born Yadwiga, or Jadwiga, Frischer. Jadwiga, a strange and jarring name to western ears, had been a popular name for centuries among Jewish girls in Poland ever since Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, married the Polish Princess Jadwiga and was crowned King of Poland in 1385. She was one of at least seven children in a poor family from an unknown village near Warsaw, an obscure little community of religious Jews and Polish peasants. Her father, who had remarried after the death of her mother before the war, was a cobbler. Little else is known about her early life. She was ten months older than Hershl. When the Nazis came to her village, she began a tortuous journey through an unknown number of work camps. Almost six years later, she was liberated by the Russians and trekked westward over the Tyrol mountains, where she ate grass and drank snowmelt to stay alive. We do not know the names of the camps in which she was interred or what work she had been forced to perform in them. One of her brothers emigrated from Poland to Israel in the 1950s, but the remainder of her family, save another brother and one older sister, were murdered. She never spoke of those who had perished.

Her sons say Yaja lived in a world of fantasy, where there were no Nazis and no Holocaust. Unlike Hershl she did not dwell on the past, but rather willed herself to obliterate it from her mind and in this way she survived beyond liberation. Hershl could not forget and, perhaps, it was his suffering that helped her forget her own. People said it was she who kept her husband in the world of the living. Just as there exists a hierarchy of suffering among survivors – some camps were worse than others – the same hierarchy prevailed in the Sperling household. Yaja had not lived through Treblinka; she told her sons, ‘I didn’t suffer like your father.’ A photograph of her after the war shows her triumphantly holding a baby over her head outside the gates of an unknown forced-labour camp. If a single image had to be chosen to commemorate Yaja Sperling’s sense of survival, it would be this. More than a celebration of life, it was a victory.

Not that the Holocaust had left her unaffected; the pair established a winking complicity. They took absurd risks together. On one occasion they stole a large mackerel from the buffet of the Danish Food Centre, a restaurant that had recently opened in Glasgow. When they were certain no one was watching Hershl stuffed the entire fish into Yaja’s handbag. Food-obsession was something they shared with other survivors and their kitchen cupboards always contained enough canned food supplies to ensure the family’s survival for at least three months. Sam said: ‘They behaved as though they were preparing for a siege.’ Food symbolised life and death for them. The theft of food was rampant in the camps, both among prisoners and guards. Guards stole prisoners’ food and sometimes killed prisoners whom they suspected of stealing food. In the camps, where all else was stripped away, hidden food equalled a life prolonged. Hershl often stole small things from shops. Whether this was habitual or intentional thrill-seaking it is impossible to know.

To begin with, I regarded Hershl and Yaja just as Sam’s slightly crazy parents. Before long, I had become a regular visitor to their house and at their kitchen table, a guest in their incongruous world of kosher food, Yiddish conversations and bouts of madness. Hershl had long-since abandoned his belief in God, for he had been a witness in places where God could not exist. Yet the Jewish motif of ‘sanctifying God’s name’ – the willingness to sacrifice one’s life in the cause of moral principles – ran like a thread through Hershl’s being and must have made his Treblinka experience all the more painful. Yaja saw the beauty of God in everything.

As parents, they granted their children extraordinary freedoms. They rarely said no. I remember drinking beer for the first time at 14, sitting with Sam at his kitchen table, his mother washing dishes and watching us with a wry expression. Hershl once demanded a meeting with the headmaster of Sam’s high school, a particularly dull and authoritarian man, and warned him never to lay a finger on his son. It was the 1970s, when Scottish school children were belted for misbehaviour, but the headmaster heeded Hershl’s warning. A man who had looked Josef Mengele in the eye was not going to be intimidated by an over-zealous school master. I remember my mother saying, ‘They have a right to be crazy.’ I also remember Hershl yelling Yiddish joyously at his wife, who would laugh. He would then turn good-naturedly to torment and tease his children with crazy word games. Deep within him, there ran a natural love of language. I did not realize then, but it was a clue.

Besides his native Yiddish, Hershl spoke good Polish and German, as well as some Russian, and later English. He also spoke an archaic Hebrew, learned faithfully in synagogue class as a child. Language came easily to him, and it was a gift to which he owed his life. In Treblinka, only German speakers were selected for the

Sonderkommando

. Those who spoke further languages increased their chances of survival because they might become useful translators for the Nazis. In Auschwitz, Dachau and the other camps, those who did not understand the language of the masters were quickly brutalised and murdered, because they were useless. They could not understand the tirades of the SS or the kapos. Hershl’s fluency in Polish – and many Jews there spoke only Yiddish and just a few words of Polish – had also been crucial and meant survival and opportunity in the aftermath of Treblinka. Yaja also spoke good Polish, and occasionally she and Hershl spoke it in the home – usually for the transmission of things they wanted to keep from Alan and Sam, who understood Yiddish and English very well. Both Sperling children inherited their father’s language gift. I remember one evening sitting down with the Sperlings in their living room to watch

Call My Bluff

, the television game show in which contestants guessed the meaning of obscure words. Alan, a highly intelligent individual with an expert knowledge of Latin, deciphered every word, a rare feat. But Hershl would always correct him on the Slavic or Germanic pronunciations. And instead of congratulating Alan for his effort, Hershl instead would throw cushions at him and little hard-boiled sweets that were always heaped in a glass bowl on the coffee table, until the room was in chaos. Hershl often behaved more like a child than his children, perhaps because his own childhood had been lost.

There was also panic in their house; but I saw little of that. The outside world was perceived as threatening and frightening. The source of that fear was the memory of the Holocaust, and their behaviour was based on the belief that some future catastrophe might catch them unawares. Every minor incident became a crisis. Sam told me later: ‘We lived as though the Gestapo were about to knock the door down.’

Sometimes crises were entirely invented. During one terrible bout of depression, Hershl became convinced Yaja was having a secret love affair. Alan told me: ‘He was going through a very difficult period, and he accused her, over and over again. It was complete nonsense. She was utterly devoted to him. If she were being accused of robbing a bank, that would have been more probable.’

I remember another time I was sitting with the family in their living room. Hershl sipped his lemon tea, and we were watching a wildlife programme on television. A pack of hyenas squabbled over the remains of a carcass. ‘So much like humans,’ Hershl said, suddenly. ‘We lived like that.’ Sam asked him several times to tell him what it was like in the camps. He was desperate to know. ‘We lived like animals,’ Hershl said. That was all. Later, as if by way of explanation, Sam told me ‘My father was in Treblinka.’ The name meant nothing to me then, because I was hearing it for the first time.

Hershl Sperling had other names. In the shtetl of Klobuck, the little town in Poland where he was born, he was Hershl Szperling, the Polish rendition of Sperling, which is also the German word for sparrow. To his relatives and friends then, he was Hershle, the extra ‘e’ added as a Yiddish inflexion of endearment. But outside the shtetl, in Polish Klobuck, he was Henick, his Polish name. In Scotland he was Henry, except to his wife; at home, and to himself, he was Hershl.

Hershl kept many secrets about his past. His children could not understand whether he was protecting them or himself. The truth is probably that he was doing both. Yet, at the same time, he transmitted his suffering to them, his helplessness and his humiliation. On rare occasions, he would talk chillingly about the Treblinka burial pits, about how he had to go into them. Once, during a trip to Israel, he had watched Sam, then about eighteen, playing a game with his nine-year-old cousin. Sam recalled: ‘He started to say that she reminded him of his sister, but then he became very upset. He started to cry and went inside. We still don’t even know his sister’s name.’

Yaja was the only one who could calm him, but she could not cure him. Psychiatrists could not help him either, nor could the anti-depressants or the other treatments they tried. They did not – could not – understand that ‘Auschwitz was nothing’. They could not possibly understand that Treblinka was not a concentration camp, and as terrible as those places were, they were not death camps. In Treblinka, Hershl had been forced to participate in the systematic murder of at least 700,000 people. Doctors did not know about the pits of burning bodies or what suffering it was to toil among them. Alan said, ‘He witnessed things that people are not intended to witness.’ In Auschwitz, Hershl was beaten by murderous kapos and he spent weeks up to his chest in icy canal water, but it was Treblinka he relived each day. Throughout his life, Hershl insisted that ‘the real horrors’ of the Holocaust were not known – but he knew. Years later, doctors diagnosed mental illness but in fact he was profoundly traumatised.