Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (9 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

This first group of doomed Jews crossed Pilsudskiego Street at the border of the ghetto, conveniently located by the Nazis near the railway station, and near the hotel in which I spent the night. Apart from the occasional traveller like me, who still feels the heartbeat of the past, Jews rarely visit this city. Yet walking up Krotka Street to Wilsona, still one of the poorer parts of town with its derelict, grey buildings, I saw a collapsed brick wall running along what was in 1942 the edge of the Częstochowa ghetto. It was impossible not to feel the presence of a vanished people here. And it was impossible not to feel their terror.

They walked until they reached the Częstochowa-Kielce railway line. The sound of chanted Hebrew grew louder. A long train of 60 freight cars stood before them. Steam billowed from the undercarriages. Some were relieved at the sight, which they believed provided evidence that they really were being sent to the east for work. Most of the people halted at a ramp, as they were ordered. Some tried to resist or run. Terrible scenes of brutality and murder ensued. Just over an hour later, the doors to all the wagons were closed. The Jewish police units were spared on this day. The movement of the locomotive leaving the city drowned out the screaming and wailing, and the cries for help. The tracks ran directly to the most murderous place on earth – the gas chambers of Treblinka.

Behind them, numerous corpses lay in pools of blood. At Krotka Street, a few Jews were ordered, under the lash of whips, to gather the dead bodies and transport them on wheelbarrows to awaiting trucks. The bodies were then driven to Kawia Street and thrown into the large pit that had been dug earlier. It seemed the world had gone insane.

* * *

The air within Hershl’s bunker was rank from the stench of human beings in close confinement for many days. We cannot know who these other people were, except that they were Jews from the ghetto, perhaps relatives – although we can be certain they existed in an atmosphere of constant fear, tension and terrible monotony. All conversation had to be conducted in whispers. Most of the time there was a deep silence, their sole method of defence, as they lay on their makeshift beds. There was probably no standing room. Their clothes and bedding crawled with lice.

Some elderly Jews join us and we lie together, hidden in the bunker, cut off from the world. We discuss our dangerous situation. We do not dare to go out in daylight. At night, we creep out into the fields to find something to eat. There are cabbages, turnips and other vegetables. We bring them back and cook them on an electric stove. At night, when it is dark, we enter the houses of the deported Jews and search through the abandoned rooms.

It seems they refused to delude themselves with hope. I have no doubt that every sound, every footstep in the street would have made them hold their breath collectively. They could not escape. Where could they run? Even in the woods, Polish partisans killed Jews. They may have imagined themselves aboard a sinking ship, as did one anonymous young Jewish woman hiding in an underground bunker during the final days of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Her diary was found as recently as 2004. This young woman’s final, desperate words read: ‘We are living by the day, the hour, the moment.’

Meanwhile, the second assault of the Częstochowa

Aktion

was launched two days later, in the early hours of 24 September. Members of the Gestapo and the SS Death’s Head squad swarmed through the ghetto, now combing Nadrzeczna, Garncarska, Targowa and Prosta streets, and drove the residents again toward the courtyard of the metal factory. The same treatment was meted out to those from the area around the old market in the south-east of the ghetto. At the factory courtyard, another selection took place. A further 7,000 were rounded up, and another 300 selected for work duty. More innocent blood ran in the street.

The following day, on the third day of the Jewish holiday of Succoth, German police cars crawled through the ghetto with megaphones and announced that all Jews sent earlier by train had arrived safely at their destination. They were told that the former ghetto inhabitants were now at labour camps in eastern Poland, and were working for the benefit of the Reich. They were told that food and warm clothing there were plentiful. At the same time, posters in Polish and German were nailed up outside the ghetto, warning that the penalty for hiding Jews was death – but for revealing Jewish hiding places, special rewards would be given. Later that day, the Gestapo came again with megaphones. They said all remaining Jews who assembled at the metal factory the following morning were to be given half a kilogram of bread, marmalade and a bowl of warm soup. The people were starving, and many complied. There was, of course, no bread or marmalade, and that morning another 7,000 Jews were marched to the railway tracks and loaded on to the train to Treblinka. More dead bodies were dumped into the pit at Kawia Street.

Eight days after the first deportation, Degenhardt instigated a fourth wave of round-ups. This time, the sweep was aimed at uncovering those Jews who had hidden themselves. Methodically, the Gestapo combed the streets of the ghetto, cellar by cellar. The Szperlings and their companions held tight. Their hiding place remained secure for most of the day. Then, near the end of the sweep, the Gestapo returned. Dogs barked ferociously. The doors of the bunker were suddenly flung open and light blasted in.

Our bunker is discovered almost at the end of the period of deportations. Whether we were betrayed by someone, or whether it is purely chance, we do not know. The commander of the deportations, Degenhardt, makes a personal appearance and commands us all to leave the bunker. We comply, because we know that if we were discovered during a second search, it will be certain death. We are taken to Przemyslowa Street, where the last deportees are just being taken away. Of the 7,000 Jews who are rounded up here, 300 men and ten women are assigned to a work-detail in Częstochowa. The remainder is forced into a large factory yard … They are destined for the furnace.

Hershl and his group were among those forced into the factory yard and destined for death.

Everyone has to take off their shoes, tie them together and hang them over their shoulders. Then begins, silent and barefoot, the march to annihilation. At the exit to the factory yard a box has been placed. Under threat of punishment by death, everybody has to throw all their valuables into it. Hardly anyone does it. As they marched on, however, their fear grows. They have second thoughts about it, and from all sides valuables, foreign currency and money are dropped by the wayside … The route of the death-march is littered with Jewish possessions.

They marched through the empty streets. Fresh corpses lay in pools of blood. Windows of abandoned ghetto apartments were smashed and curtains blew through them in the breeze. Dogs on leashes held by the SS barked and lurched at the marching Jews. They marched again to Pilsudskiego Street until they came to the Częstochowa-Kielce railway line. Now the planned mayhem was again enacted. Whips were cracked and people were beaten. To escape the violence, they climbed up on the ramp and into the freight cars. Hershl and his family were among them. We can only imagine the terror of the little red-haired girl who I imagine had clung to the side of her older brother, who in turn clung to his parents. The only alternative at that moment was death. They chose life as they were driven into the terrible crush of the freight car.

* * *

The following month, the day after the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah and a week after the death train containing Hershl and his family had left for Treblinka, a fifth round-up occurred in Częstochowa. Included in that selection were the Jewish police and their families. Most of the

Judenrat

were also deported. By the following day, some 35,000 Jews from the Częstochowa ghetto had been shipped to Treblinka for the Final Solution.

Early the following June, SS and Gestapo units swept through the tiny streets of the remaining so-called Small Ghetto with an even greater air of arrogance than usual. Degenhardt came in person to supervise the final phase of this important work. The business of liquidation and Jewish extermination in this city was almost complete. Vehicles screeched to a halt just beyond the old square and units armed with whips and guns began to spread into the streets.

No sooner had the first door been smashed in, and the first cries of ‘

Raus

’ heard, a shot rang out and a member of the SS lay dead in the street. Abruptly, a cheer went up and, although armed with just a few pistols and rifles and some home-made grenades, several dozen Jewish fighters began to open fire on the Gestapo from prearranged positions in bunkers. The resistance surprised them and, for the first time, Nazi blood flowed in the streets of Częstochowa. The Germans pulled back and, shortly afterwards, stormed the bunkers. The uprising was crushed with overwhelming force. Thousands more were sent to Treblinka that day. The remaining 4,000 Jews were transferred to two slave labour camps at the city’s munitions factories. The Częstochowa ghetto was finally destroyed.

CHAPTER SIX

The demonic and impossible idea to murder every Jew in Europe sprang from the depths of Hitler’s hatred. Yet the savage phenomenon we now know as the Holocaust – the systematic murder of six million Jews and some 250,000 Gypsies, as well as many political prisoners and homosexuals – could not have occurred without the venomous undercurrent of anti-Semitism and racial prejudice. The roots of this hatred had been embedded for centuries across Europe. We can only look back in horror at the ease with which all the petty spites and hatreds were harnessed and mobilised by demagogues and religious fanatics during the terrible years of the Third Reich. There were around eleven million Jews in Europe in 1939. The big problem for the Nazi planners was what to actually do with these people whom Hitler had doomed. In the beginning, they had no idea.

Hitler himself, it seems, had no specific plan either. It began with the broad notion of German racial imperialism and the creation of

Lebensraum

, or living space, in the east. The idea was to kill, deport, or enslave all the Slavic populations, whom they considered

untermenschen

, or sub-human, and to repopulate the lands with Germans. As the Wehrmacht swept across Poland, every foot soldier, lieutenant and commander was aware of the underlying determination to render the expanding German Reich

Judenrein

, or cleansed of Jews. All claims of ignorance are lies. Yet the chaotic terror unleashed by the Wehrmacht in Klobuck, Częstochowa and elsewhere throughout Poland during the first weeks of the war was not the implementation of systematic annihilation, for no such plan had as yet been devised. According to Nazi propaganda, all these people were less than human anyway, so it did not much matter how they were treated. In the absence of a specific plan, Hitler had only to express the depths of his hatred, and ambitious Nazis vied to outdo one another in brutality and, at the planning level, to produce proposals that would transform the Führer’s vague ideological notions into realistic and murderous programmes.

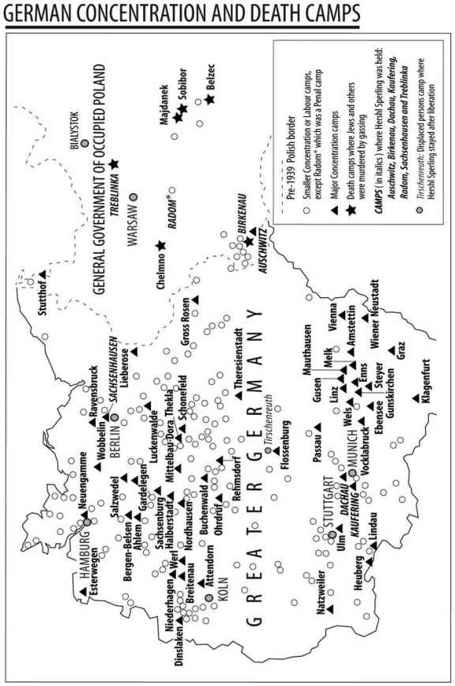

Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazi Party’s chief racial theorist in charge of building a so-called human racial ladder to justify Hitler’s ideology, signalled early on that the Führer’s wishes could not be realised at once, but rather via a series of practical steps. Rosenberg, at a conference in Berlin at the end of September 1939, indicated that all Jews – including those who had already been expelled from the Reich – were to be resettled in newly acquired Polish territories in the area ‘behind Warsaw and around Lublin’, between the Vistula and the Bug rivers. Another strip of land between the German and Jewish settlement areas was designated as the ‘primitive’ Polish region. To achieve this enormous demographic shift, it was clear that first the Polish intelligentsia – considered to be teachers, clergy, nobles and anyone capable of resistance – would have to be ‘rendered harmless’, another Nazi euphemism that in reality meant either transport to concentration camps, or murder. The Jews, meanwhile, were to be concentrated in ghettos in the cities to ‘have a better possibility of control and later of deportation’, according to the minutes of a meeting between Reinhard Heydrich and his division heads in Berlin that same month.

The mass murder of Europe’s Jews began in late June 1941 when four

Einsatzgruppen

, special SS killing squads under orders from Heydrich’s Reich Security Office – the central organ of SS bureaucracy – advanced with the German Army into the USSR. Here, at locations such as the Rumboli forest near Riga, at Polnat near Vilna, Babi Yar at Kiev, and at numerous other sites in the occupied parts of the Soviet Union, more than one million Jewish victims were shot to fall into ravines and pits. The decision to organise and build death camps emerged from the gradual realisation that mass extermination could not be achieved with bullets alone. The vastness of the numbers involved created an undesired public spectacle, and there were also concerns about the psychological impact on the killers.

One eyewitness, Eric von dem Bach-Zelewski, the head of some 50,000

Einsatzgruppen

and affiliate members – including SS troops, police and local auxiliaries on the eastern front – described what happened during Himmler’s visit to Minsk during the killing of 100 Jews. As the firing started, Himmler became highly agitated. Then von dem Bach-Zelewski told him:

R

eichsführer

, those were only a hundred. Look at the eyes of the men in this commando, how deeply shaken they are. Those men are finished for the rest of their lives. What kind of followers are we training here? Either neurotics or savages.

The green light for systematic annihilation can be traced back to 31 July 1941. On that day, in Berlin, Heydrich was handed Hermann Göring’s infamous order:

I hereby charge you to carry out preparations as regards organisational, financial, and material matters for a total solution of the Jewish question in all the territories of Europe under German occupation.

There had been deliberations for months over whether the extermination should be conducted before or after Germany’s military victory. Then, some time in late December, according to separate diary entries by Goebbels and Himmler, the Führer gave the final go-ahead for the full-scale construction of what were to become the three Operation Reinhard extermination camps – Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka.

The decision followed the completion of the experimental gassings in the remote Polish village of Chelmno. On 7 December 1942, 800 Jews from Kolo, about nine miles from Chelmno, were taken to a large house on an unused estate and held for the night. The next morning, the first 80 Jews were forced naked into a large van. This vehicle, they were told, would take them to a bathhouse. Some sensed the danger. Yet those who attempted to stop before the ramp were driven, some savagely beaten, into the van. When the van was full, the door was locked, the engine started, and carbon monoxide was pumped into the interior through a specially constructed pipe. Four or five minutes later, when the cries and struggles of the suffocating victims were heard no more, the van was driven to the Chelmno wood about two miles away, and the corpses were dumped. The van returned to the house ten or eleven times until all 800 Jews were gassed. After the Kolo murders, the Reich authorities went on to exterminate all the Jews from four other nearby towns, as well as several hundred gypsies. That month alone, some 20,000 people were exterminated at Chelmno. The 7 December round-up occurred on the same day that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Hitler’s decision to begin full-scale extermination was also likely to have been based on other factors. On 5 December the Wehrmacht was halted at the gates of Moscow by a massive Soviet counter-attack and the vicious Russian winter, the first significant reversal of German military fortunes. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor two days later and brought the US into the conflict, and Germany now had a world war on its hands. Hitler must have understood that a German victory was no longer a certainty – but still his plans for the annihilation of European Jewry were not to be jeopardised. The ‘Jewish problem’, it was reasoned, could also be solved more easily under the cover of war, regardless of the outcome.

Heydrich then set in motion the administrative and organisational coordination of the plan. This orchestration of mass murder occurred at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942. The conference had originally been planned for 2 January, but was delayed because of the Pearl Harbor attack. Heydrich told the conference the ‘Final Solution’ would include more than eleven million Jews. He stated bluntly: ‘Europe would be combed of Jews from east to west.’

Josef Buhler, State Secretary of the General Government for occupied Poland, asked the conference that the Final Solution begin in occupied Poland because there was no transportation problem there, and most of the Jews in the ghettos were already too weak to be of use to the German war effort. The request was approved.

Adolf Eichmann, at his trial in Jerusalem in 1960, described Heydrich, his work done at the Conference:

I remember that at the end of this Wannsee Conference, Heydrich, Muller and my humble self, settled down comfortably by the fireplace, and that then for the first time I saw Heydrich smoke a cigar or cigarette, and I was thinking: today Heydrich is smoking, something I have not seen before. And he drinks cognac – since I had not seen Heydrich take any alcoholic drink in years. After this Wannsee Conference we were sitting together peacefully, and not in order to talk shop, but in order to relax after the long hours of strain.

Within a matter of weeks, the plans for the three extermination camps – Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka – took shape.

At the end of September 1941, Hitler had appointed Heydrich as acting

Reichsprotektor

of occupied Bohemia and Moravia. The radio reported on his inauguration at Prague Castle, where he returned after the fateful conference at Wannsee. But his reign was short-lived. On 27 May 1942, Heydrich was fatally wounded in Prague. Two British-trained Czech partisans, Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik were parachuted into German-occupied Czechoslovakia with the aim of carrying out the assassination attempt on Heydrich in a plan that originated with the exiled president of Czechoslovakia, Edward Benes, in London. The General had been riding in his open car in the Prague suburb of Kobylisy at around 10.30am when Gabcik jumped in front of the vehicle. He drew a concealed British-made Sten sub-machine gun from his coat, but it failed to fire. Gabcik ran to the other side of the street and began firing with his pistol. At the same time, Kubis threw a grenade that exploded near the car, and the vehicle screeched to a halt. Heydrich did not appear to be seriously injured and tried to return fire, but his pistol was not loaded. His driver, a man named Klein, also tried to fire at the assailants, but in the confusion of the moment he accidentally pressed a button that released a cartridge. Gabcik attempted to escape through the streets, but was chased by the driver. Gabcik turned and fired wildly, and hit Klein in the leg. The two assassins went into hiding. Kubis escaped from the scene after stealing a woman’s bicycle.

Although Himmler sent his best doctors, Heydrich reportedly died in extreme pain in a Prague hospital. He was 38. The cause of death was said to be septicaemia, which he had contracted from the bacteria in the horsehair and upholstery fragments in the car seat that had been driven into his body by the explosion.

The Nazi retaliation was savage, with the dual aim of revenge and warning against further armed resistance. On 10 June all males over the age of sixteen in the village of Lidice, 22 kilometres northwest of Prague, were massacred and the women were sent to concentration camps. The next day, the same retribution was meted out in the village of Lezaky, which was burned to the ground. The Nazis trumped up a connection between the assassination and the two villages. In all, around 5,000 lives were blotted out in retaliation for the death of this single monster.

Meanwhile, Kubis and Gabcik were hiding in the Church of St Cyril & Methodius in Resslova Street with five other members of the Czech resistance for several weeks after the attack until they were betrayed by a German spy amongst their number. The Nazis surrounded the church on 18 June. The partisans barricaded themselves in the crypt of the church and tried desperately to dig their way into the subterranean sewer network. The Germans pumped water and smoke into the crypt but the partisans refused to surrender. The Germans eventually broke through the barricade and Kubis, Gabcik and the other resistance fighters died in the gun battle that followed. The six-foot hole they dug in the darkness of the crypt remains today as an eerie memorial.

After Heydrich’s death, the extermination camps of Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec were completed and put to work on their demonic task. The project, which brought about the murder of something close to 1,700,000 Jews at these killing centres, was named Operation Reinhard in his honour.

Two months later, on 19 July 1942, Himmler met with Odilo Globocnik in Lublin, the Operation Reinhard commander, and Friedrich-Wilhelm Krueger, the SS and police chief for the entire General Government of Occupied Poland, to discuss the planned killing operations. Himmler now ordered that the ‘resettlement’ – another Nazi euphemism for deportation and murder – of all Jews in the General Government was to be completed by the end of 1942.

The savagery that was triggered in Częstochowa on 22 September – as witnessed and recorded by the teenage Hershl Szperling – marked Degenhardt’s activation of

Aktion Reinhard

. Hershl’s premonition that his march toward the tracks in Częstochowa had been ‘the road to death’ was correct.