Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (20 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

The risk was enormous, given the rewards on offer for information about the Jews and the rumours that many of them were carrying large quantities of valuables, which was certainly true in Hershl’s case. Yet they were desperate. The fate of Hershl and his group were now in the hands of the inhabitants of this house.

One glance at the woman tells me that she realises what I am. ‘You must have escaped from Treblinka,’ she exclaims. The state I am in, my clothes, and above all the expression of desperation on my face have all given me away. I am prepared for the worst.

However, chance worked in his favour on this occasion. He had stumbled upon the home of an apparently decent family. Yet it must surely have been strange for Hershl, after eleven months in a death camp, to be standing inside a house.

The woman reassures me, saying that I must not be afraid, that she will help me as much as she can. She can’t hide me, however. The SS are snooping around and searching all the villages in the area. She is not prepared to expose herself and all her family to mortal danger. She gives me bread and milk, and tells me to come back at eleven o’clock at night. At the appointed hour, all three of us are in her house. This time her husband and daughter are also there. We discuss the situation and decide that the best thing would be to go to a particular place and jump on to the roof of the moving train. At that particular point, the train moves with a speed of ten kilometres per hour at most. We have no other way out and we agree to try this.

They give us a substantial supper and bread and eggs for our journey. As an expression of our gratitude, we leave them twenty gold dollars.

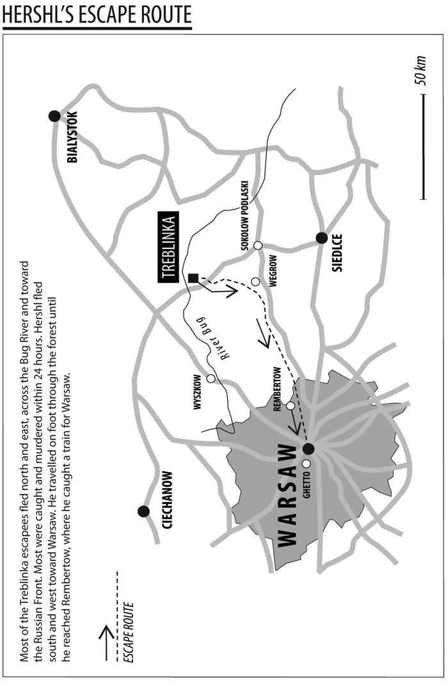

At some point on their southward journey, the group turned west or south-west, and eventually they hit the main Bialystok to Warsaw railway line.

Under cover of darkness we set out on our way. We come to the agreed place, but we decide not to jump on to the roof of the moving train after all, because we might fall through into the train itself. Instead, we carry on by foot until we reach Rembertow.

It would have taken them several days travelling through the woods to reach the village of Rembertow, avoiding security police and their tracker dogs, also the Ukrainians and Poles who continued to pursue the Jews long after the Germans had given up.

* * *

Behind them, in Treblinka, a massive clean-up operation was under way. The work was supervised by Stangl, who was worried that the escape would be blamed on him. The prisoners who had remained behind, along with about 100 Polish prisoners from the Treblinka penal facility, were used to put the camp back in order. The barracks that had been burned down during the uprising were cleared away and not reconstructed.

Under the directives of Operation Reinhard, 25,000 Jews still in the ghetto of the old industrial city of Bialystok, near today’s Polish-Belarusian border, had to be exterminated. About two weeks after Hershl arrived in Rembertow, a transport of 78 freight cars containing 7,600 Jews arrived at Treblinka on 18 and 19 August. These were the last transports to arrive at the camp. All of them were gassed and their bodies burned. Between 22 August and 21 September, single wagons loaded with the sorted belongings of the final murdered victims were sent from Treblinka to Lublin, capital of the General Government of Occupied Poland for distribution. In a matter of weeks, Stangl and a number of others from Operation Reinhard, including the fanatical anti-Semite Christian Wirth, were transferred to Trieste for anti-partisan combat on the Italian front. The posting was intended as a death sentence. Not only had the Jewish survivors of Operation Reinhard been witness to its terrible truth, but so had its commanders.

Two further Bialystok transports continued on to extermination centres at Majdanek and Auschwitz. The last remaining transport from the city, which was made up entirely of children, crossed the Polish landscape towards Theresienstadt, in annexed Czechoslovakia. These children were used as part of a Nazi bargaining tool under a plan orchestrated by Himmler in early 1945. It resulted in the release of 1,200 Dutch and Swiss Jewish children to Switzerland after $1.25 million was placed by Jewish organisations into Nazi-controlled Swiss bank accounts. The remainder, which included 400 Bialystok ghetto orphans, were sent to the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

After Stangl left for the Italian front, the sadist Kurt Franz was appointed Treblinka’s third and final commander. Franz’s task was to dismantle the camp and remove all traces of its existence.

* * *

Rembertow, now an eastern suburb of Warsaw, was in 1943 an independent town of 20,000 people on the edge of a wild area of open swamps, meadows, peat bogs and dense forest. Hershl emerged from the woods some time during the first week of August. Earlier that year, the Germans began disconnecting the electricity and the smell of the substitute carbide lamps permeated the town. It heaved with the destitute. Rows of miserable, dilapidated wooden buildings housing poverty-stricken families, dosshouses, and shady businesses stood along Ulica Żołnierska, the town main’s street. Nearby stood a German garrison, where Ukrainians, Latvians, Belarusians and Lithuanians who had been captured or had deserted from the Red Army were being trained. Żołnierska Street thronged with the desperate, many of them drunk on vodka, on their final spree before being sent to the Russian front. Such circumstances fuelled an enormous black market in goods and false identification papers. Hershl and his group walked these streets, attempting to melt into the crowd. Fortunately, their dreadful appearance was not out of place: ‘We have decided to go on from there by train, but we haven’t any Polish money. We sell a diamond ring worth twenty thousand zlotys to a peasant, getting only five hundred zlotys for it.’ Rembertow station thrummed with people. Trains came and went. Passengers charged the trains as they stopped, as if they were launching an attack. He writes: ‘Quaking with fear we buy our tickets.’

* * *

Samuel Rajzman also fled east then south from Treblinka, but he did not emerge from the woods as quickly as Hershl. He escaped through the camp’s fencing complex into the forest with a group that included one of the camp’s few Jewish girls, the girlfriend of survivor Joseph Siedlecki. Even in the tragic reality of Treblinka, intimate relationships developed between a few a male prisoners and young Jewish women in the camp. Siedlecki, perhaps also acting on Rajzman’s guidance, like Hershl, chose to flee south and he later met up in the forest with Rajzman and his group. However, in the heat of a pursuit, they were separated again, and Siedlecki’s girlfriend – the name of this young woman is not known – ended up staying with Rajzman’s group.

Siedlecki, a former Polish Army soldier whose wife was gassed on arrival at Treblinka, ended up in Warsaw, where he managed to acquire papers and spent the rest of the war passing as a gentile Pole working with a construction firm attached to the German army. Siedlecki, who later emigrated to America and became a maitre d’ at Grossinger’s Hotel in upstate New York, where Hershl years later visited him, told interviewer Gitta Sereny in 1971: ‘No, I don’t know what happened to her.’ However, Rajzman and his group stayed in the forest. One day after returning from a village where he had gone to get food for his group, Rajzman found them all dead on the forest floor. Among them was Siedlecki’s girlfriend, killed by Polish partisans, who discovered the Jews in their hiding place and were doubtless aware that they were in possession of diamonds, gold and other valuables.

Rajzman’s wandered through the forest alone, eking out the food he brought for his group, too fearful to return to a village and wary of every noise in the forest. Years later, Rajzman told Hershl – who in turned passed the story on to his sons – how in desperation one evening he approached a lit farmhouse on the outskirts of a village. The farmer looked at him and took him into his home. He then fed him and told him he could remain hidden at the farm. We do not know for how long.

One Sunday afternoon, most likely the first Sunday after the escape of the previous Monday afternoon, the farmer returned from church and told Rajzman that the priest there had given a sermon about Treblinka’s escaped Jews. He told the congregants that it was their duty as Poles and Catholics not to harbour any of the ‘Christ-killers’ in their homes. Rajzman asked him what he was going to do and the farmer responded by telling him, as related to Hershl’s son Sam, that ‘it was not a priest he had heard in his church, but the devil himself’ and he agreed to hide Rajzman. We do not know where he was hidden or how long Rajzman stayed at the farm, amidst the random searches by the Germans, Ukrainians and Polish posses, however, it was long enough for him and the farmer to develop a close relationship. After the war, Rajzman kept in contact with the farmer and sent him and his family gifts each year until Rajzman’s death in 1979.

Rajzman stayed hidden in the forest for a full year. He does not reappear until 1944, where he is seated at the centre of a photograph of twelve survivors, most likely taken somewhere behind the lines of the advancing Red Army. By January 1944, the Soviet forces had already thrust into what had been pre-1939 Polish territory. The photograph is captioned ‘Reunion of Treblinka survivors’ and lists the names of those photographed from left to right, many of them in leather jackets and boots, the attire of partisans.

* * *

Hershl does not reveal what occurred on that train journey between Rembertow and Warsaw. I imagine him, a sixteen-year-old boy with his Treblinka cap pulled down over his face and covering his shaven head. Miraculously, he arrived in Warsaw safely. He then parted company with the three who had escaped with him.

The Warsaw he entered was a city entirely under German control. The overwhelming majority of the 300,000 Jews who had once lived there were already ash in the Treblinka sand. Meanwhile, most Warsaw Poles had been reduced to poverty. Records reveal that Warsaw residents received the lowest food rations anywhere in German-occupied Europe and correspondingly the city became an enormous centre for illegal commerce.

We do not know how long Hershl remained in Warsaw, but probably only a few days. The Warsaw ghetto was now empty and in ruins. We can only imagine Hershl’s reaction as he peered over the broken ghetto walls into the desolate shells of silent, burned-out buildings.

SS documentation I obtained from the International Tracing Service, which manages a vast repository of wartime and post-war records in the small German resort town of Bad Arolsen, reveals that Hershl had tasted freedom for just seven days before being apprehended in or near the town of Koluszki in central Poland. The address he provided at his capture was Warschawska 43, Częstochowa, a main thoroughfare in the city, part of which ran across the small ghetto. It is unclear whether this location was a former address, a destination or even an address invented on the spur of the moment to disguise the fact that he was on the run.

Sam told me, ‘He was captured on a train. My father said there were two Germans – I presume they were SS, or maybe soldiers – who saw him from the other end of the carriage, and they started shouting, ‘

Jude

,

Jude

’, you know, ‘Jew, Jew’. I think my father tried to run away, but they caught him. He said one wanted to let him go. I think he said something like, ‘He’s young. We should just leave him.’ But the other one said they had to turn him in. So they arrested him. From there, as far as I know, they took him straight to Auschwitz. But he never said any more about it than that.’

Hershl’s written account is also unhelpful. Between the inconclusive utterance that ‘[we] manage to get to Warsaw safely’, which marks the end of his account, and a paragraph-long epilogue, in which he names some of the Treblinka survivors he met in a displaced persons camps two years later, there is yet another void in Hershl’s story.

I had no desire to return to Poland, and I did not want to visit any more death camps. I had had enough. Sam was right – for Jews, Poland was a graveyard. But where did the Angel of Death Dr Josef Mengele, the mysterious position of Hershl’s tattoo, Auschwitz itself and all that occurred afterwards fit into Hershl’s final tragic act? There was more to discover. I knew I would have to return.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Just before I left for my third trip to Poland, I confirmed an appointment with Dr Franciszek Piper, the chief historian at Auschwitz, and I mailed off some further requests to the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen and the records department at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. I wanted to know what there was of Hershl in history. I wanted to see his name in black and white in historical documents. Placing him objectively at specific points in history corroborated and confirmed his suffering.

I travelled with my wife on a westbound train from Kraków to Oswicim one early sunny morning in mid-September 2007. Oswicim is the town the Germans renamed Auschwitz in the wake of the 1939 invasion. In the carriage were a few Polish commuters and three sets of visitors – Japanese, American and British – each of them holding Auschwitz travel guides. Less than fifteen minutes into the journey, I saw a swastika scratched on a signpost hanging above the platform of Kraków– Lobzow station. I checked my guidebook and read that the town of Oswicim had been founded 700 years earlier and that its name in Polish meant ‘a place to be made holy’. Auschwitz held as many as 20,000 prisoners at one time and it murdered more than two million in its gas chambers and through starvation, forced labour, lack of disease control, executions, and medical experiments. It has become the symbol of Nazi evil. Yet those words Hershl had uttered kept returning to me: ‘Auschwitz was nothing. Auschwitz was a walk in the park.’

As the train sped west, bales of hay stood in fields that bordered lush forests. It was between summer and autumn – the season in which Hershl had travelled to Treblinka – and the leaves were just beginning to turn. The commuters disembarked at Kraków Business Park, a modern complex of concrete and glass, created as part of a regional economic initiative in 1997. How strange it must be each day to travel the tracks that had once been the route to death. I saw more anti-Semitic graffiti – a Star of David hanging from a gallows. Meadows gave way to dense forest and green hills rose gently in the north. Just past Krzeszowice station, lines of rusting boxcars stood motionless in rows on half-a-dozen parallel tracks. On the platform at the station at Trzebinia, once the site of a large Auschwitz sub-camp, a burly, moustachioed man wearing a black leather skip-cap and jacket walked the platform with a cigarette dangling from his mouth and his hands in his pockets, but he did not get on the train.

At Oswicim, a nondescript industrial town, a local bus took us to the camp. We walked through the main gate, infamously bearing the words ‘

Arbeit Macht Frei

’. The complex was a circus of visitors and guides touring the camp and its museum of terrifying exhibits. I thought it odd how the presence of these tourists did not detract from the horror of the place. But I didn’t want to see any more atrocities. I already knew what murderous carnage and tortures had been perpetrated here. I had come in 1989, during the months after Hershl had taken his life, and I walked along the deserted pathways between crumbling brick buildings and studied the photographs of prisoners’ faces in its then-small museum. I remember the mounds of glasses and hair. I also remember the hotel receptionist in Kraków telling me there was ‘nothing to see in Auschwitz’. It was a different place these days. Now I walked directly through the throng of school parties and tourists to my appointment with Dr Piper in his office at Block 24. The building had once served as the Auschwitz brothel, staffed by women who had been selected for the purpose soon after they emerged from the trains.

Dr Piper was a gentle, sad-eyed Pole with a scholarly grey beard and glasses. He had worked as a historian here for more than 40 years. I told him I was conducting research for a book that I was writing about a man named Hershl Sperling, who had been among those who had escaped during the Treblinka uprising, and that he had ended up in Auschwitz some time in late 1943. He was later moved to Dachau before the Russians arrived, I told him.

Dr Piper nodded, and smiled politely, but I saw suspicion in his eyes. I discovered later that Holocaust deniers had edited film interviews with him in an effort to support perverse historical interpretations.

‘Fact or fiction?’ he asked, matter-of-factly. I told him that Hershl had killed himself in 1989, and that he was my friend’s father. Dr Piper’s suspicion gave way to a look that was both emotional and disturbed. He raised one eyebrow. ‘This is not a typical story,’ he said. I could sense his interest pique. I smiled, pleased at this small acknowledgement. ‘Is there a memoir?’ Dr Piper asked, hopefully.

‘In part,’ I said. ‘He left a testimony, a kind of eyewitness account, that was published in a journal in 1947, but it more or less stops after the escape from Treblinka. Auschwitz is not mentioned. I know he was here, because he said so and, of course, he had a number tattooed on his arm. I have the number here.’ I flicked open my notebook. ‘I was hoping you might be able to tell me when he came and what kind of work he did. Is there a record of him here?’

Dr Piper did not speak as he rose from his seat and went to a computer on his desk, on which stood mountains of papers and books. I told him Hershl’s number, or at least the number that Sam had given me – 154356 – and that it had been placed high up on the inside of his arm. I was also curious about the tattoo’s position, but at this stage, I did not even know if the six-digit number that Sam had reeled off to me before I left – seared on his brain since childhood, but not seen for at least eighteen years – was correct. I waited.

Dr Piper said suddenly. ‘I’ve got him. Heniek Szperling, number 154356. Born 10 March 1927.’ It was an extraordinary moment. Here was Hershl, my friend’s father, on the database of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. He was now real in history, and there could be no denials.

Dr Piper remained at the computer for a few minutes longer, apparently searching for information. I looked out of the window into the courtyard toward a brick wall. ‘My own cousin was hanged on the gallows, just below that window,’ he said, and smiled politely. At last, he came out from behind his desk and sat down again in the chair in front of us.

‘Well, I have some information,’ he said. ‘Your Mr Szperling arrived at Auschwitz on 2 October 1943, from a penal camp at Radom. He came with 869 prisoners on that day, and 194 of them were women. The numbers started at 153522 and ran to 154391.’

This was new information. I later learned that conditions were brutal in the prison camp at Radom, a town in central Poland, not too distant from where he was arrested in Koluszki. It all made sense. Earlier that year, some 1,600 Jews from the Radom camp were rounded up in the so-called ‘Palestine Aktion’ in which they were told they were going to Israel. They were instead sent to Treblinka. Hershl had probably cleaned the boxcars in which these Radom Jews had come and dragged their dead to the pit at the Treblinka Lazarett. From the date of his arrest on 9 August 1943 to his arrival at Auschwitz, I now knew that he had spent something like seven weeks at the prison camp.

‘No one had any idea he was at Radom, at least not to my knowledge,’ I said. ‘They seemed to have held him for a long time there. Obviously, they didn’t know he escaped from Treblinka.’ Dr Piper nodded intently.

‘The interesting thing about this particular transport is that it did not undergo a selection,’ he said.

‘What does that mean?’

‘This was a transport of Polish prisoners – political prisoners and so-called intellectuals – and Mr Szperling was among them. It is quite clear the Germans did not know he was Jewish. This was unusual, because the Germans were very suspicious. I mean to say they were extremely suspicious. All they needed to do was to check for circumcision.’ He took a deep breath, then added, ‘I can also tell you this was one of the biggest Polish transports, and when they arrived at Auschwitz, they all stayed together.’

‘Are you absolutely sure?’ I asked, now scribbling madly in my notebook. I thought again of how Hershl’s language skills and his daring had kept him alive. Hershl would have used the Yiddish word,

chutzpah

, for his own behaviour in those days. He had been arrested as a Jew on the train in Koluszki, but had somehow managed to become a Pole by the time he entered Auschwitz. I said, ‘This is extraordinary, quite a thing to pull off.’

‘It is very unusual, and, yes, I am certain. There is a ‘P’ next to his name and number,’ Dr Piper said. ‘Polish, not Jew.’

‘Does it say what he did here, his work?’

‘I’m sorry. When the Germans evacuated Auschwitz on 18 January 1945, they destroyed 90 per cent of the prisoner records. Ten per cent have remained. Before you leave, you should check with Auschwitz archives. There may be more information there.’

‘I see.’ Dr Piper’s eyes seemed to radiate sadness.

‘There is something else,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘On 10 February 1944, Heniek Szperling, prisoner number 154356, was sent to the

strafkompanie

, that is to say the Birkenau penal commando.’

‘Do we know how long his sentence was, and what offence he committed?’ I asked. Dr Piper shook his head.

‘Most likely he tried to escape, but it’s also possible he was either engaged in the resistance movement or else in black market activities. These were the three reasons prisoners were most often sent to the

strafkompanie

.’ He now leaned forward in his chair and stared at me. ‘Let me tell you, this was the worst punishment in Auschwitz. The prisoners died from executions, punishments or exhaustion. Many prisoners in that commando were murdered by kapos. That was where they assigned all the cruellest kapos.’

Hershl, of course, had experience of all three potential infringements. I have no difficulty imagining him engaged in all of them – trying to escape, organised resistance and also black marketeering.

* * *

About a week later, I called Sam and told him what I had learned. I was struck now more than ever by Hershl’s contention that ‘Auschwitz was nothing’. It seemed a sacrilegious comment, given the suffering and death that had occurred there.

‘At one level, I think, even in a place like Auschwitz, he was still glad to be away from Treblinka,’ Sam said. ‘At another level, it’s about the hierarchy of suffering, which exists even though I suppose a lot of people don’t want to admit it. But survivors are aware of it. Some people suffered more than others. There was even a hierarchy of suffering in our house. My mother used to always say, “I didn’t go through what your father did” – and she lost both her parents and spent years in a labour camp.’

I told Sam about the harsh conditions of the

strafkompanie

and that Dr Piper had described it as the ‘worst punishment in Auschwitz’. Records revealed that Hershl was sent to the penal commando in Birkenau on 10 February 1943, and on that day 41 others from the Polish contingent with whom he had arrived joined him. Alas, the length of his sentence is unknown because of incomplete records.

The prisoners were isolated in the notorious BII section of Birkenau. The workload was murderous. What remains of the Book of the Penal Company reveals that some of Hershl’s fellow Poles died within days of arrival. Food was distributed at the whim of the block leader. Punishments were severe. Often the unit worked up to their waists in water to maintain the Königsgraben canal, the main drainage ditch that ran through the camp. They worked in winter without socks, in Dutch clogs, and clad in ticking. There was no toilet, only a bucket – although Hershl was used to that after Treblinka. His barrack held 36 wooden bunk beds, and inmates were squeezed in five or six across a wooden plank. As many as 500 prisoners could be lodged in a single barrack.

‘Still,’ said Sam, ‘compared with Treblinka, Auschwitz was nothing. Treblinka was the big thing for my father. Everything went back to Treblinka. The rest didn’t really seem to matter. Do you remember

Colditz

, that programme about the prisoner of war camp in Germany? My father refused to watch it. He called it a holiday camp. Remember the prisoners used to sit around in deck chairs? Auschwitz was nothing and Colditz was a holiday camp, he insisted.’

‘You know, I went to the Auschwitz archives department to see if they had any more information, and I ended up filling out forms about your father. It turned out they didn’t even know that he’d survived the war.’

‘So now they’ve updated the records?’

‘Now they know everything I know. Beforehand, they didn’t even know he was Jewish or that he was from Klobuck or that he’d moved to Scotland.’

‘That’s good. Now the Holocaust record is a little more complete.’ Sam’s voice trailed off and a long silence hung.

‘Are you okay?’ I asked, after a moment.

‘I’m remembering something.’

He was remembering an odd remark Hershl had made one evening years earlier. It must have been January 1977. The Sperling family had just finished their meal. Yaja had finished in the kitchen and was sitting next to Hershl on the sofa. Alan, who was then 26, and Sam, who was nearly sixteen, almost the age of Hershl in Auschwitz, were sitting in the two easy chairs facing the television. Like much of the rest of the British public that night, they were awaiting the start of the new epic mini-drama called

Roots

, the story of an American family tracing its ancestry back to Kunte Kinte, the Mandinka tribesman in the Gambia who was captured by slave traders and brought to Virginia and sold.

Yaja used to slip out of the room and Hershl would call after her in Yiddish. A few moments later she brought him his glass of lemon tea, which he sipped while he watched the television. As the drama unfolded during the first two-hour episode, Kunte Kinte was forced to wear leg irons attached to an iron ball and chain to prevent him from escaping.

Sam said, ‘My father turned to me and said suddenly, “I had to wear shackles like that in Auschwitz.” He said a lot of crazy things, which no one believed. I remember he also said something about the Germans not knowing he was Jewish, which seemed really crazy to me because we’re talking about Auschwitz.’