Tutankhamen (13 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

The narrow space between the outermost shrine and the chamber walls yielded an assortment of artefacts which seem to modern eyes bafflingly random, but which had been deliberately chosen by the undertakers for their ritual significance: two calcite lamps, a wooden goose, two boxes, two wine jars, an unidentifiable âritual object', eleven magical oars, a double shrine, two âAnubis fetishes' (an animal skin, filled with embalming fluid, suspended on a pole), gilded wooden hieroglyphic symbols meaning âto awake' and a funerary bouquet. Hidden from view in the painted walls, four niches held the magical bricks that would assist Tutankhamen in his rebirth. Opening off the Burial Chamber an open doorway revealed yet another room packed with objects including a gleaming golden canopic shrine, an object of such significance and beauty that it brought a lump to the normally undemonstrative Carter's throat. This âTreasury' would be boarded up and left untouched until 1927. Amazed by what they had seen, the weary visitors left the tomb after 5 p.m. and, in true British style, went for tea.

The Times

broke the news to the waiting world:

The Times

broke the news to the waiting world:

Today, between the hours of 1 and 3 in the afternoon, the culminating moment in the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb took place, when Lord Carnarvon and Mr Howard Carter opened the inner sealed doorway â¦The process of opening this doorway bearing the Royal insignia and guarded by protective statues of the King had taken several hours of careful manipulation under intensive heat. It finally ended in a wonderful revelation, for before the spectators was the resplendent mausoleum of the King, a spacious, beautifully decorated chamber, completely occupied by an immense shrine covered with gold inlaid with brilliant blue faience.

Â

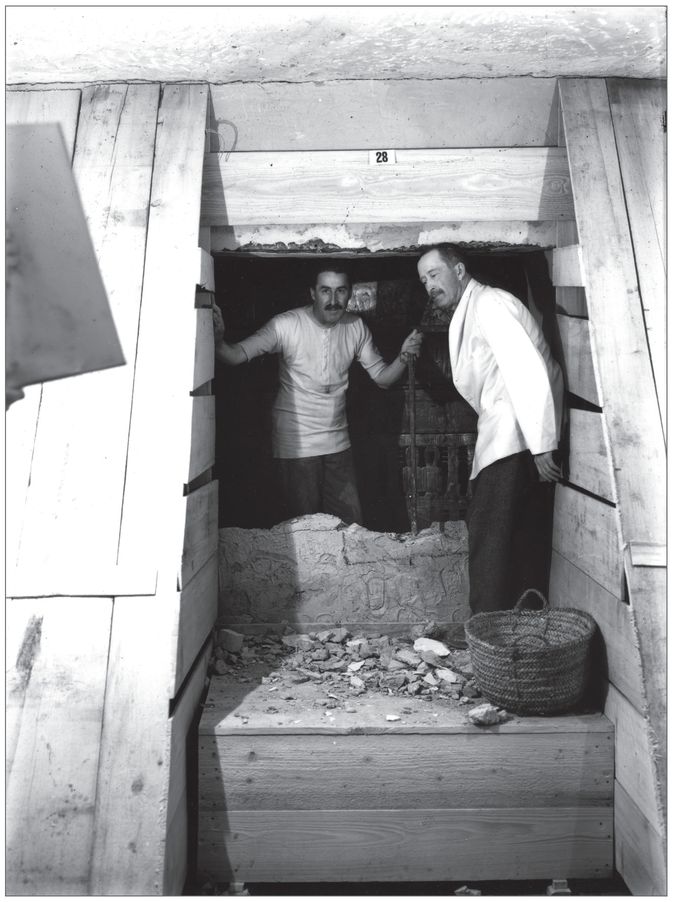

6. Carter (left), Carnarvon and the partially dismantled, plastered and sealed wall to the Burial Chamber.

The next couple of days were taken up with private viewings, and private luncheons, for Egyptologists and distinguished visitors; among the latter were Queen Ãlisabeth of the Belgians and her son Prince Léopold. This was to be the first of several royal visits and the queen, an enthusiastic amateur Egyptologist, became something of a nuisance to the archaeologists as she interrupted their work. It was a nuisance, too, when the portly General Sir John Maxwell got stuck in the still-small hole in the Burial Chamber wall. Mervyn Herbert's diary records, with some sympathy, that it took four men pushing and pulling to free him âwith a noise like a champagne cork and with injury to what he wrongly described as his chest'. There would always be an uncomfortable tension between the scientific work of the excavators, who very much saw the tomb as their own private laboratory, and the exploitation of the tomb as a public spectacle by the

authorities and, on occasion, the archaeologists themselves. The Valley had become the ultimate elite tourist attraction, with Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn acting as guides; anyone who could claim even the slightest acquaintance with any member of the team felt free to turn up, uninvited but with a letter of introduction, for a personal tour which would inevitably bring all work to a standstill.

authorities and, on occasion, the archaeologists themselves. The Valley had become the ultimate elite tourist attraction, with Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn acting as guides; anyone who could claim even the slightest acquaintance with any member of the team felt free to turn up, uninvited but with a letter of introduction, for a personal tour which would inevitably bring all work to a standstill.

The general public was condemned to loiter with the journalists beyond the tomb perimeter wall. This was not, perhaps, as bad as it seems, as every object removed from the tomb had to pass before their gaze en route for the sanctuary of the conservation tomb. This endless parade of grave goods â the constant anticipation that something exciting might at any moment appear â ensured that interest in the tomb increased rather than decreased. Luxor was swamped with visitors â the more enterprising hotels set up tents in their gardens where tourists could sleep, for one uncomfortable night only, on narrow cot beds â and the expedition lived in near-siege conditions:

The tomb drew like a magnet. From a very early hour in the morning the pilgrimage began. Visitors arrived on donkeys, in sand-carts, and in two-horse cabs, and proceeded to make themselves at home in The Valley for the day. Round the top of the upper level of the tomb there was a low wall, and here they each staked out a claim and established themselves, waiting for something to happen. Sometimes it did, more often it did not, but it seemed to make no difference to their patience. There they would sit the whole morning, reading, talking, writing, photographing the tomb and each other, quite satisfied if at the end they could get a glimpse of anything â¦

14

14

Those unable to visit Egypt, wrote: the volume of post received by the Luxor post office first doubled, then tripled, and the telegraph office was overwhelmed by the sheer number of journalistic dispatches. Carter was bombarded with correspondence from all over the

world, from well-wishers, beggars, schoolchildren, scholars, people wanting to buy, or sell, antiquities, people offering money for public lectures, and what might be loosely termed âeccentrics', including those who believed themselves to be reincarnated Egyptians. All wanted a reply from the celebrity archaeologist.

world, from well-wishers, beggars, schoolchildren, scholars, people wanting to buy, or sell, antiquities, people offering money for public lectures, and what might be loosely termed âeccentrics', including those who believed themselves to be reincarnated Egyptians. All wanted a reply from the celebrity archaeologist.

Conditions within the tomb were hot, humid and extremely stressful. A serious, never explained quarrel between Carter and Carnarvon, which ended dramatically with Carter briefly banning Carnarvon from his house, was a sign that the team needed a break from the tomb, from the press, from the public and from each other. On 26 February 1923 the tomb was closed; the next day the laboratories were shut and the team dispersed. While Carter typically chose to hide himself away in his Luxor house, Lucas went to Cairo and Callender to Armant. Mace accompanied Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn as they sailed southwards to spend a few peaceful days at Aswan. It was on this trip that Carnarvon was bitten on the cheek by a mosquito, an everyday occurrence on the Nile. But soon after his return to Luxor, he sliced the scab off the bite while shaving. Here, accounts of the tragedy vary. Most state that Carnarvon treated the wound immediately with iodine (already an invalid, he travelled with a well-stocked medical chest); a few that he allowed the wound to bleed freely, and inadvertently allowed an âunspeakably filthy' fly to settle on it.

15

The wound quickly became infected, and Carnarvon started to feel unwell. A few days' bed rest â insisted upon by Lady Evelyn â soon had him feeling fit again, but then there came a sudden relapse. Unwilling to admit just how ill he felt, Carnarvon travelled to Cairo to start discussing the division of finds with the Antiquities Service. Here his condition deteriorated rapidly. Blood poisoning set in, and pneumonia followed. Lady Carnarvon flew to Cairo with her husband's personal doctor, Dr Johnson, and Lord Porchester, Carnarvon's heir, sailed from India. At 1.45 a.m. on 5 April 1923, Carnarvon died. His body was embalmed in Egypt and then returned to England for burial on Beacon Hill, part of the Highclere estate.

15

The wound quickly became infected, and Carnarvon started to feel unwell. A few days' bed rest â insisted upon by Lady Evelyn â soon had him feeling fit again, but then there came a sudden relapse. Unwilling to admit just how ill he felt, Carnarvon travelled to Cairo to start discussing the division of finds with the Antiquities Service. Here his condition deteriorated rapidly. Blood poisoning set in, and pneumonia followed. Lady Carnarvon flew to Cairo with her husband's personal doctor, Dr Johnson, and Lord Porchester, Carnarvon's heir, sailed from India. At 1.45 a.m. on 5 April 1923, Carnarvon died. His body was embalmed in Egypt and then returned to England for burial on Beacon Hill, part of the Highclere estate.

Carter, who had travelled to Cairo to support Lady Evelyn throughout her father's illness, and had remained to assist Lady Carnarvon with the funeral arrangements, returned to Luxor to wind down the excavation. The finds were packed into crates, and transported along the Décauville railway (a tramway allowing open carts to be pushed along a temporary track) to the river. This was not quite the slick operation that it sounds; there was not enough track to cover the distance from the Valley to the river, and so it had to be dismantled and repositioned as the train of carts progressed. At the river, the crates were loaded on to a steamer. When the ship arrived in Cairo on 21 May, Carter was ready to meet it. It took just three days for the artefacts to be unloaded, transported to the museum, unpacked and put on display.

The Second Season: 1923 â 4The Concession to work in the Valley expired with Carnarvon's death. However, the Antiquities Service were keen that the clearance of the tomb should continue, and they were unwilling to finance it themselves. Work therefore started as planned in October 1923, with Lady Carnarvon allowed to finish her husband's work, but not to conduct any further excavations in the Valley. In addition to his other duties, Carter now assumed Carnarvon's role of liaising with the authorities and the press: a development which those who remembered the infamous âSakkara affair' had reason to view with some foreboding. Carter was a man of many talents, but diplomacy was not one of them.

From the very beginning of the season, there were problems. Carter provides us with an unusually tactful and essentially uninformative summary of events that would lead to the closure of the tomb, and threaten the security of its remaining contents:

Gradually troubles began to arise. Newspapers were competing for

âcopy', tourists were leaving no efforts untried to obtain permits to visit the tomb: endless jealousies were let loose; days which should have been devoted to scientific work were wasted in negotiations too often futile, whilst the claims of archaeology were thrust into the background. But this is no place for weighing the merits of a controversy now ended, and it would serve no good purpose to relate in detail the long series of unpleasant incidents which harassed our work. We are all of us human. No man is wise at all times â perhaps least of all the archaeologist who finds his efforts to carry out an all-absorbing task frustrated by a thousand pin-pricks and irritations without end. It is not for me to affix the blame for what occurred, nor yet to bear responsibility for a dispute in which at one moment the interests of archaeology in Egypt seemed menaced.

16

âcopy', tourists were leaving no efforts untried to obtain permits to visit the tomb: endless jealousies were let loose; days which should have been devoted to scientific work were wasted in negotiations too often futile, whilst the claims of archaeology were thrust into the background. But this is no place for weighing the merits of a controversy now ended, and it would serve no good purpose to relate in detail the long series of unpleasant incidents which harassed our work. We are all of us human. No man is wise at all times â perhaps least of all the archaeologist who finds his efforts to carry out an all-absorbing task frustrated by a thousand pin-pricks and irritations without end. It is not for me to affix the blame for what occurred, nor yet to bear responsibility for a dispute in which at one moment the interests of archaeology in Egypt seemed menaced.

16

Carter believed that time-wasting visitor numbers should be controlled by banning informal visits, while implementing a series of planned open days. After a great deal of negotiation, and repeated journeys between Luxor and Cairo, the matter was to a certain extent settled. The Antiquities Service would issue visitor permits which would limit the number of tourists demanding access to the tomb. In theory this should have worked, but in practice the Service issued permits to more or less anyone who applied for them, while Carter was prone to break his own rule, finding it difficult to refuse admission to prominent Egyptian families or important diplomatic parties. The problem of press access was more difficult. Carter suggested that it could be resolved quite simply by âemploying' Arthur Merton, correspondent of

The Times

, as an official member of the excavation team. Merton would issue daily reports which

The Times

would receive in time for the evening edition and the Egyptian newspapers would receive the next day. Thus, he hoped, news from the Valley would break more or less simultaneously in London and Cairo, and other newspapers could take their information from the published

bulletins. Naturally enough, the representatives of Reuters and the

Morning Post

lobbied tirelessly against Carter's appointment of Merton, while the Egyptian press, and growing numbers of Egyptian nationalists, continued their campaign against colonialist archaeology.

The Times

, as an official member of the excavation team. Merton would issue daily reports which

The Times

would receive in time for the evening edition and the Egyptian newspapers would receive the next day. Thus, he hoped, news from the Valley would break more or less simultaneously in London and Cairo, and other newspapers could take their information from the published

bulletins. Naturally enough, the representatives of Reuters and the

Morning Post

lobbied tirelessly against Carter's appointment of Merton, while the Egyptian press, and growing numbers of Egyptian nationalists, continued their campaign against colonialist archaeology.

Petty differences over press and public access to the tomb were extremely trying, but they were a symptom rather than a cause. Carter had become caught up in a political situation which he could do nothing to resolve. The British Protectorate was coming to an end and Egypt was becoming a modern, independent state. Fuad I had proclaimed himself king in 1922; a new constitution had been announced in 1923; there were to be general elections in 1924. The Antiquities Service was still run by a Frenchman, Pierre Lacau, but the politically astute Lacau was no longer prepared to be seen indulging foreign excavators in what many were beginning to regard as the exploitation of Egypt's heritage. Soon, a new rule was imposed: an Inspector of the Antiquities Service must always be present to oversee work at the site. Then, on 1 December 1923, came the demand that Carter submit a formal list of all members of his excavation staff for the approval of the Antiquities Service. Today this is standard procedure; the Antiquities Service has the right to veto anyone whom they deem unfit to work on any archaeological site. But in the 1920s it was seen as an unprecedented impertinence, and a less than subtle attack on the newly appointed press spokesman, Merton. Carter attempted to argue, but there was no room for negotiation. Lacau stood firm: â⦠the Government no longer discusses, but informs you of its decision'.

Meanwhile, work continued amid all the distractions. Carter had removed the two guardian statues from the Antechamber, and had completely demolished the partition wall separating it from the Burial Chamber. Even with the wall missing, the team were forced to work in uncomfortably cramped conditions as they struggled to dismantle

the unwieldy, heavy and extremely fragile shrines, which fitted so neatly into the Burial Chamber that, without ruling out the possibility that they were merely the inner shrines of a far larger set, they seem to have been purpose-designed for the space. As Carter recollected: âwe bumped our heads, nipped our fingers, we had to squeeze in and out like weasels and work in all kinds of embarrassing positions'.

17

It soon became apparent that the ancient carpenters, too, had struggled in the restricted space. Despite a plethora of instructions scratched or painted on to the shrine components, the shrines had not been properly assembled. There were dents and gaping cracks, carpenter's debris was left on the floor and, most surprising of all, the shrine doors were misaligned so that they faced east, not west. This unusual arrangement was probably adopted to take advantage of the extra space offered by the Treasury; we can only wonder at the effect it would have had on Tutankhamen's spirit as he set off on his final journey moving away from, rather than towards, the setting sun.

the unwieldy, heavy and extremely fragile shrines, which fitted so neatly into the Burial Chamber that, without ruling out the possibility that they were merely the inner shrines of a far larger set, they seem to have been purpose-designed for the space. As Carter recollected: âwe bumped our heads, nipped our fingers, we had to squeeze in and out like weasels and work in all kinds of embarrassing positions'.

17

It soon became apparent that the ancient carpenters, too, had struggled in the restricted space. Despite a plethora of instructions scratched or painted on to the shrine components, the shrines had not been properly assembled. There were dents and gaping cracks, carpenter's debris was left on the floor and, most surprising of all, the shrine doors were misaligned so that they faced east, not west. This unusual arrangement was probably adopted to take advantage of the extra space offered by the Treasury; we can only wonder at the effect it would have had on Tutankhamen's spirit as he set off on his final journey moving away from, rather than towards, the setting sun.

Other books

Enchantment by Nikki Jefford

Silent House by Orhan Pamuk

The Yoghurt Plot by Fleur Hitchcock

Primal Scream by Michael Slade

Laura Lippman by Tess Monaghan 05 - The Sugar House (v5)

In Bed With a Stranger by India Grey

The Mirror of Fate by T. A. Barron

The Billionaire's Woman Trilogy by Keana Black

Vankara (Book 1) by West, S.J.

Sarai's Fortune by Abigail Owen