Tutankhamen (9 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

This atmospheric description may owe something to Tyndale's artistic imagination: others tell us that the exposed head was bare of flesh, and that the face had been crushed by a rockfall. If Tyndale is correct, his account suggests that there was originally more flesh on the mummy than Davis would have us believe. However, the fact that Davis could not immediately determine the mummy's gender suggests that some parts, at least, had rotted away.

The golden shrine had unambiguously been a part of Tiy's burial equipment, and the canopic jars were obviously female. The positioning of the mummy's arms, according to Ayrton, also suggested a female burial. It is therefore not too surprising that Davis immediately assumed that he had discovered Queen Tiy. This would have been a great find for him. In the days before the discovery and public display of the Berlin bust of Nefertiti, it was Tiy who was regarded as the most intriguing, most glamorous, and most important of the 18th Dynasty queens. Davis sought to prove his own identification by calling on the services of a local doctor, Dr Pollock, and an American obstetrician who was spending the winter in Luxor. He tells us that the two pronounced the remains female on the basis of the wide pelvis. The accuracy of Davis's report is, however, open to some doubt, as Weigall (who did not believe the body to be female) confirms: âI saw Dr Pollock in Luxor the other day, who denies that he ever thought that

it was a woman, and says he and the other doctor could not be sure.'

30

Davis never wavered in his conviction that he had discovered Tiy, and it was as

The Tomb of Queen Tiyi

that he published the tomb.

it was a woman, and says he and the other doctor could not be sure.'

30

Davis never wavered in his conviction that he had discovered Tiy, and it was as

The Tomb of Queen Tiyi

that he published the tomb.

Davis did not feel that the bones had more to offer, and it was left to Weigall to pursue the matter. Several months after their unwrapping, having soaked the bones in paraffin wax to strengthen them, he sent them to Cairo Museum to be examined by Smith. Smith had been expecting the bones of an elderly woman. Opening the bone box, he found instead the bones of a man of about twenty-five years of age.

Although he had a string of spectacular discoveries to his name, Davis was becoming disillusioned with his inability to find an intact royal burial. Had he but realised it, his team had actually discovered three crucial clues to Tutankhamen's whereabouts:

Â

Clue 1:

During his 1905 â 6 excavation season Ayrton found a simple faience cup âunder a rock'. The cup bore Tutankhamen's name and was, perhaps, part of swag dropped by the robbers who raided his tomb soon after the funeral.

During his 1905 â 6 excavation season Ayrton found a simple faience cup âunder a rock'. The cup bore Tutankhamen's name and was, perhaps, part of swag dropped by the robbers who raided his tomb soon after the funeral.

Â

Clue 2:

On 21 December 1907 the team discovered a stone-lined pit (KV 54) housing a collection of large storage vessels. The jars were opened, and then quickly forgotten. Herbert Winlock, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, was present to record the sorry story:

On 21 December 1907 the team discovered a stone-lined pit (KV 54) housing a collection of large storage vessels. The jars were opened, and then quickly forgotten. Herbert Winlock, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, was present to record the sorry story:

Sometime early in January 1908 I spent two or three days with Edward Ayrton, to see his work for Mr Davis in the Valley of the Kings. When I got to the house the front âlawn' had about a dozen gigantic white pots lying on it where the men had placed them when they brought them back from the work. At that time Ayrton had

finished a dig up in the Valley of the Kings just east of the tomb of Ramesses XI [KV 18: now believed to be the tomb of Ramesses X]. He had quite a job on his hands to find something to amuse Sir Eldon Gorst, the British diplomatic agent who was to be Mr Davis' self-invited guest soon. Sir Eldon had written a very strange little note, which I saw, saying to Mr Davis that he had heard that the latter's men found a royal tomb every winter and requesting, as he intended to be in the Valley of the Kings in a few days, that all discoveries be postponed until his arrival⦠Davis had found the jewelry [sic] of Queen Tawosret in another tomb, but that was not sufficiently spectacular, and as he had opened up one of the great pots and found a charming little yellow mask in it, everybody thought they were going to find many more objects in the other jars ⦠That evening I walked back over the hills to the Davis house in the Valley, and I have still got a picture in the back of my head of what things looked like. What in the morning had been fairly neat rows of pots were tumbled in every direction, with little bundles of natron and broken pottery all over the ground. The little mask which had been taken as a harbinger of something better to come had brought forth nothing and poor Ayrton was a very sick and tired person after the undeserved tongue-lashing he had had all that afternoon.

31

finished a dig up in the Valley of the Kings just east of the tomb of Ramesses XI [KV 18: now believed to be the tomb of Ramesses X]. He had quite a job on his hands to find something to amuse Sir Eldon Gorst, the British diplomatic agent who was to be Mr Davis' self-invited guest soon. Sir Eldon had written a very strange little note, which I saw, saying to Mr Davis that he had heard that the latter's men found a royal tomb every winter and requesting, as he intended to be in the Valley of the Kings in a few days, that all discoveries be postponed until his arrival⦠Davis had found the jewelry [sic] of Queen Tawosret in another tomb, but that was not sufficiently spectacular, and as he had opened up one of the great pots and found a charming little yellow mask in it, everybody thought they were going to find many more objects in the other jars ⦠That evening I walked back over the hills to the Davis house in the Valley, and I have still got a picture in the back of my head of what things looked like. What in the morning had been fairly neat rows of pots were tumbled in every direction, with little bundles of natron and broken pottery all over the ground. The little mask which had been taken as a harbinger of something better to come had brought forth nothing and poor Ayrton was a very sick and tired person after the undeserved tongue-lashing he had had all that afternoon.

31

Among the material discovered in the jars were seal impressions bearing Tutankhamen's name, linen bundles of natron salt, floral funerary collars (which Davis tore apart in order to demonstrate their strength), and the miniature gold mummy mask mentioned by Winlock. The Antiquities Service was not interested in this valueless jumble and, while the small gold mask was sent to Cairo Museum, the other finds went the Metropolitan Museum with a different small mask (probably from KV 51); a well-meaning but ill-recorded substitution which was to cause much confusion to future generations of scholars.

32

Many years later, Winlock identified the jar contents as the remnants of the embalming materials and funerary feast of Tutankhamen. He

believed that these objects, which had ritual significance and so could not be simply thrown away, had been buried in an unfinished tomb near the main tomb. This idea was subsequently refined so that the cache became the material cleared from the passageway of Tutankhamen's tomb after the first robbery, immediately before the passageway was filled with stone chips. Thus it included items which were deliberately left in the passageway of Tutankhamen's tomb plus, perhaps, odd items dropped by the robbers. Finally, following the 2004 discovery of KV 63, a New Kingdom cache tomb yielding embalming materials, broken pots and floral collars, it has been suggested that the pit may have been a separate original and untouched part of Tutankhamen's funerary provision.

33

32

Many years later, Winlock identified the jar contents as the remnants of the embalming materials and funerary feast of Tutankhamen. He

believed that these objects, which had ritual significance and so could not be simply thrown away, had been buried in an unfinished tomb near the main tomb. This idea was subsequently refined so that the cache became the material cleared from the passageway of Tutankhamen's tomb after the first robbery, immediately before the passageway was filled with stone chips. Thus it included items which were deliberately left in the passageway of Tutankhamen's tomb plus, perhaps, odd items dropped by the robbers. Finally, following the 2004 discovery of KV 63, a New Kingdom cache tomb yielding embalming materials, broken pots and floral collars, it has been suggested that the pit may have been a separate original and untouched part of Tutankhamen's funerary provision.

33

Â

Clue 3:

In 1909 the team discovered the âChariot Tomb': a small, undecorated chamber (KV 58) which yielded an uninscribed alabaster figurine and the gold foil from a chariot harness inscribed with the names of Tutankhamen and his successor Ay, whose name is given both as a commoner and a king.

In 1909 the team discovered the âChariot Tomb': a small, undecorated chamber (KV 58) which yielded an uninscribed alabaster figurine and the gold foil from a chariot harness inscribed with the names of Tutankhamen and his successor Ay, whose name is given both as a commoner and a king.

Convincing himself that âthe Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted', Davis published the Chariot Tomb as the long-lost, and rather disappointing, tomb of Tutankhamen.

34

His book betrays a somewhat split personality. Its title â

The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou â

leaves no room for doubt over the nature of the find. However, the chapter describing the artefacts is more cautiously titled âCatalogue of the Objects Found in an Unknown Tomb, supposed to be Touatânkhamanou's'. Contributing to Davis's publication, Sir Gaston Maspero suggested that the Chariot Tomb was not the original tomb of Tutankhamen, but a re-burial:

34

His book betrays a somewhat split personality. Its title â

The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou â

leaves no room for doubt over the nature of the find. However, the chapter describing the artefacts is more cautiously titled âCatalogue of the Objects Found in an Unknown Tomb, supposed to be Touatânkhamanou's'. Contributing to Davis's publication, Sir Gaston Maspero suggested that the Chariot Tomb was not the original tomb of Tutankhamen, but a re-burial:

Such are the few facts that we know about Touatânkhamanou's life and reign. If he had children by his queen Ankhounamanou or by another wife, they have left no trace of their existence on the

monuments; when he died, Aiya replaced him on the throne, and buried him. I suppose that his tomb was in the Western Valley, somewhere between or near Amenothes III [Amenhotep III] and Aiya [Ay]: when the reaction against Atonou [the Aten] and his followers was complete, his mummy and its furniture was taken to a hiding place⦠and there Davis found what remained of it after so many transfers and plunders. But this also is mere hypothesis, the truth of which we have no means of proving or disproving as yet.

35

monuments; when he died, Aiya replaced him on the throne, and buried him. I suppose that his tomb was in the Western Valley, somewhere between or near Amenothes III [Amenhotep III] and Aiya [Ay]: when the reaction against Atonou [the Aten] and his followers was complete, his mummy and its furniture was taken to a hiding place⦠and there Davis found what remained of it after so many transfers and plunders. But this also is mere hypothesis, the truth of which we have no means of proving or disproving as yet.

35

Few were convinced by Davis's argument. Howard Carter, a former excavation partner of Davis, realised that the âChariot Tomb' was not a tomb, royal or otherwise, but a storage chamber. He believed that Tutankhamen still lay in the Valley, waiting to be found. But, while Davis still held the sole concession to excavate, he could only stand by and watch.

Â

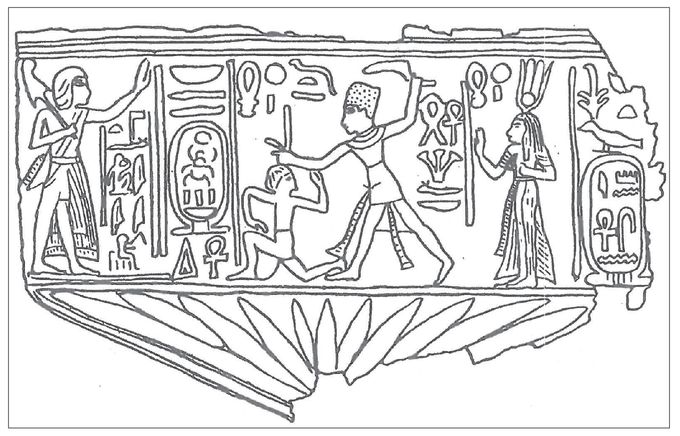

4. Scrap of gold foil from a chariot harness, recovered from KV 58. Tutankhamen is shown smiting a stereotypical enemy, while his consort Ankhesenamen stands behind him and his successor, Ay, stands before him.

Carter's career had seen a meteoric rise and a sudden, catastrophic fall. In 1891, aged just seventeen and with no formal education, he had travelled from Norfolk, England, to work as a draughtsman with Percy Newberry. He learned his craft recording the decorated walls of the rapidly deteriorating Middle Kingdom rock-cut tombs at Beni Hasan and el-Bersha. A valuable five-month secondment with Flinders Petrie at Amarna had allowed him to learn the art of scientific excavation from its master. Petrie, who was to become known as the âfather of Egyptian archaeology', was one of the first to recognise that artefacts could not simply be snatched greedily from the ground, and his methods were to have a profound effect on Carter's own working practices. Carter completed his training by working as a draughtsman for Ãdouard Naville at the Deir el-Bahri memorial temple of Hatshepsut. Here he took full responsibility for copying the scenes on the temple walls, and the magnificent publication of the temple includes work by both Howard Carter and his elder brother Vernet, who spent a season working at Deir el-Bahri.

In 1899 Carter was appointed Chief Inspector of Antiquities for southern (Upper) Egypt. Based at Luxor, he assumed responsibility for the 500-mile stretch of southern sites including the Theban monuments and the Valley of the Kings. During his tenure Carter fitted iron doors to protect the more important Valley tombs, and installed electric light in six of them. He also built a large donkey park to accommodate the ever-increasing numbers of tourists visiting the Valley. Then, after five very successful years, Carter swapped positions with the northern Inspector, Quibell, and moved to Cairo. Initially, things went well. Then, on the afternoon of 8 January 1905, came the âSakkara Affair': a group of drunken Frenchmen forced their way into the Sakkara Serapeum (the burial place of the divine Apis bulls),

manhandling the native inspectors and guards. Carter, summoned to the fracas, gave his men permission to defend themselves against the French. Weigall, who was taking tea with Carter that afternoon, explained events in a letter to his wife, Hortense:

manhandling the native inspectors and guards. Carter, summoned to the fracas, gave his men permission to defend themselves against the French. Weigall, who was taking tea with Carter that afternoon, explained events in a letter to his wife, Hortense:

Fifteen French tourists had tried to get into one of the tombs with only 11 tickets, and had finally beaten the guards and burst the door open ⦠Carter arrived on the scene, and after some words ordered the guards â now reinforced â to eject them. Result: a serious fight in which sticks and chairs were used and two guards and two tourists rendered unconscious. When I saw the place afterwards it was a pool of blood.

36

36

For an early twentieth-century Englishman to encourage ânatives' to assault Frenchmen was, to say the least, politically naive. As the dispute escalated into a full-scale diplomatic battle, the British Consul-General, Lord Cromer, asked Carter to apologise to the French Consul. Carter refused: a refusal that many found hard to understand, as the apology was considered a very little thing (no one expected him to mean it) and his refusal to bend in any way childish and unhelpful. Maspero, himself French, was infuriated by his employee's inability to compromise. He was eventually able to resolve the matter without the apology, but he retaliated by restricting Carter's authority, and transferring him to the dull Delta backwater of Tanta. Hurt, and angered by what he saw as a lack of official support, Carter resigned from the Antiquities Service on 21 October 1905.

Other books

In the King's Arms by Sonia Taitz

Master of the Circle by Seraphina Donavan

Kill Decision by Suarez, Daniel

Happy Endings: Finishing the Edges of Your Quilt by Mimi Dietrich

Hard To Handle (Teach Me Book 2) by RC Boldt

La siembra by Fran Ray

Curio by Evangeline Denmark

Second Chance by Angela Verdenius

Paint it Black: 4 (The Black Knight Chronicles) by Hartness, John G.

Personal Statement by Williams, Jason Odell