Ugly Beauty (15 page)

Authors: Ruth Brandon

Bénouville’s testimony concerned one of those

incidents that now reads like something out of an action movie, but which were

quite commonplace during the dark and dramatic days of the Occupation. One of

Schueller’s Resistance contacts, a man named Max Brusset, notified him that a

delegate of the Provisional Government in Algiers wanted to meet him. The

meeting was to take place at Brusset’s apartment at 28, boulevard Raspail. It

was agreed that Schueller would prepare a report concerning certain questions,

and deliver it Saturday morning. Needing a little longer, he asked to delay the

delivery until Monday morning at eleven. But at nine o’clock Monday, there was a

phone call from Brusset: he had the flu, Schueller shouldn’t come. In fact, at

seven that morning the Gestapo had arrived at the apartment. Brusset’s

sixth-floor bedroom gave onto a terrace, from which he had been able to jump

onto another terrace on the fifth floor and enter the apartment from which he

was now phoning. He was able to contact all save one of the people who had been

due to meet that morning; that one arrived as arranged, carrying incriminating

papers, was arrested, and almost certainly shot. Bénouville knew Brusset, and

had promised him that he would provide an authenticating certificate for this

story when he returned to Paris.

55

The panel

accepted Benouville’s evidence and recommended a

relaxe

.

The hearings for industrial collaboration, however,

which began in 1946 and were not resolved until two years later, had been more

problematic. The panel found that Schueller’s Resistance activities were not

enough to outweigh the evidence that he had collaborated with the Germans. He

had organized lectures in his factories, promised help to men who volunteered to

fight alongside the Germans, funded the MSR, published

La

Révolution de l’économie

with its anti-union tirades, devised the

economic policy of the RNP and encouraged the Relève. The panel did not feel

that the various Resistance activities he had brought to their notice

counterbalanced this, and found him guilty. In addition to disqualifying him

from business, the panel also threatened to forward the evidence to the Court of

Justice, which might have confiscated his assets, sentenced him to national

disgrace, to a prison term, or even to death.

And if Schueller was not guilty of collaboration,

who was? Not only did his name appear in RNP and MSR literature alongside those

of Marcel Déat, who was sentenced to death, and Eugène Deloncle, whom only

assassination saved from a comparable fate, but he had left an indelible trail

in numerous articles, pamphlets, and broadcasts, all urging collaboration; his

book

La Révolution de l’économie

had been published

on the same list as the works of Hitler himself. Acts or motives might remain

cloudy, but the published word was one thing that could not be denied.

Once again, however, Bénouville saved him. Twice—at

the first hearing, and again after the guilty verdict—he sent urgent letters,

stressing his desire to testify on behalf of the accused, visiting the judge and

the Préfet, apologizing when business took him away from Paris at the crucial

moment. Schueller, he insisted, was a victim of his fixation on proportional

salaries, which had led him into various imprudent actions. But he had been of

inestimable help to Bénouville.

56

Bénouville

got his way, and Schueller was let off.

Such solidarity between resisters and collaborators

was not unusual during the

épuration

. As Schueller’s

own activities demonstrated, channels of communication between the two sides had

always remained open. During the Occupation, collaborators often put in a word

for a Resistance figure in trouble. Now those who had been helped, helped in

their turn. Bénouville testified in this way on behalf of many old friends. What

was interesting about his efforts for Schueller, however, was that the two had

met only once, and then briefly (when Schueller, anxious to buy himself onto the

winning side, had promised financial aid when Bénouville needed it). Indeed,

Bénouville insisted that Schueller had never approached him personally for help.

What he had done, he had done for Max Brusset. Even so, it seems surprising that

he should have put quite so much effort into getting Schueller cleared. Why had

he done so?

The answer, like everything else about Schueller,

could be traced back to the life rules he had evolved. The way both Schueller

and Rubinstein conducted their family affairs would be decisive in the

intermingling of their stories. And Bénouville, for Schueller, was family—albeit

that family was a surrogate one, and Bénouville only a tangential member.

[

1

] This

may well have been true. At least in Britain, people ate more

healthfully in wartime, when food was rationed, than they have ever done

since.

[

2

] The

person who selected Oradour as a suitable site for German reprisals was

none other than Jean Filliol, Schueller’s colleague in MSR. In 1943 he

joined the Milice, the dreaded Vichy paramilitary police, and in 1944

was put in charge of the Limoges region, in which Oradour is

situated.

[

3

] Raymond

Berr was managing director of the chemicals firm Kuhlmann, and was

killed in Auschwitz. Hélène died in Bergen-Belsen five days before it

was liberated. She was twenty-three.

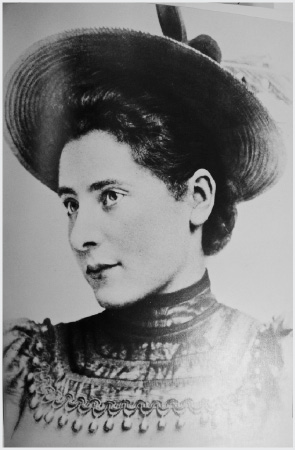

HR aged sixteen, before she left Krakow.

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

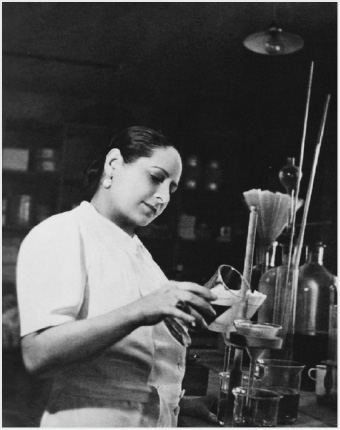

Helena Rubinstein milling parsley in her Saint Cloud

“kitchen,” 1932. Here was where she always felt happiest. Fresh flowers and

herbs were favorite ingredients for beauty creams.

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Madame Rubinstein the scientist: as she liked to see

herself and project herself to the world.

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Helena Rubinstein by Marie Laurencin, 1934. She was

sixty-two years old, but you would never guess it from this portrait, which

showed her as an “Indian Maharanee.”

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Helena Rubinstein with her surviving sisters,

l to r:

Manka, Helena, Stella, and Ceska, 1963.

Photo: Jean-Paul Cadé/Helena

Rubinstein Foundation

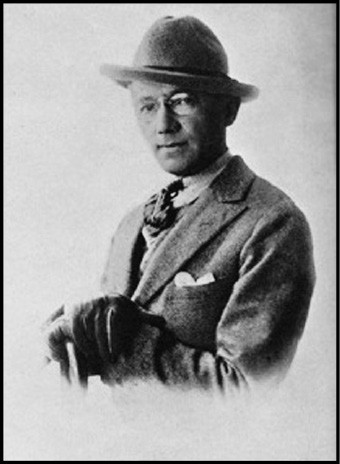

Edward Titus, the first Mr. Helena Rubinstein.

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Helena Rubinstein at eighty-six, by Graham

Sutherland. When she first saw this picture, Rubinstein hated it, commenting, “I

never imagined I looked like this.” But after the painting was exhibited and

admired in the Tate Gallery, she changed her opinion: “I had to admit, it’s a

masterpiece.”

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Prince Artchil Gourielli, Rubinstein’s second

husband, on holiday in St. Moritz, 1949. Pleasures like this were one of the

many advantages of being Mr. Helena Rubinstein.

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

Patrick O’Higgins, Helena Rubinstein’s goy, leaving

Australia at the end of his and Rubinstein’s 1958 visit.

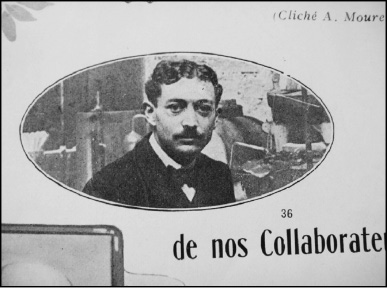

Eugène Schueller in 1909, the young chemist making

his way in the world. From an insert in the first issue of

Coiffure de Paris.

L’Auréole–the 1905 hairstyle that gave its name to

L’Oréal.

Coiffure de Paris: October

1909