Ugly Beauty (16 page)

Authors: Ruth Brandon

Eugène Schueller giving a lecture, Paris, 1941.

Archive, Mémorial de la Shoah,

Paris

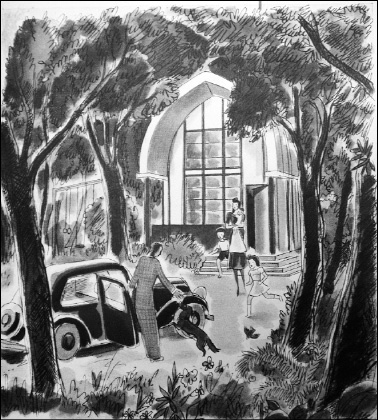

Schueller’s design for an ideal home, gothically

arched for maximum light, and complete with an ideal family, including a dog, a

car, and three children. Note that it is the wife who holds the baby. From

Le Deuxième salaire

, popular illustrated edition,

1940.

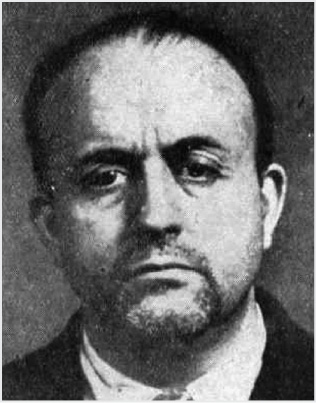

Eugène Deloncle, founder of La Cagoule and

Schueller’s colleague in the Mouvement Sociale Révolutionnaire, 1940.

Jacques Corrèze aged thirty-three, at the time of

the Cagoule trial, 1945.

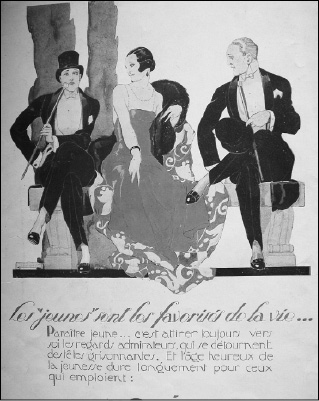

“The young are life’s favorites. . . . And youth

lasts longer for those who use L’Oréal.”

L’Oréal ad, 1923

Jean Frydman in 1944, at the time of the

Liberation.

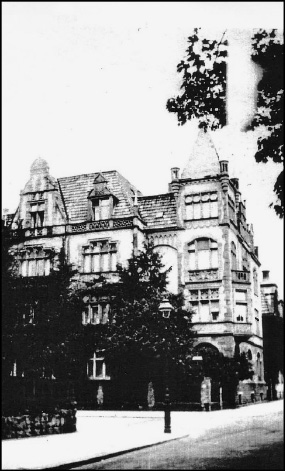

The stolen Rosenfelder house in Karlsruhe.

Courtesy Monica

Waitzfelder

André Bettencourt in 1973 when he was acting

Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Official photo, Archives

Diplomatiques

Helena Rubinstein’s New York drawing room, 1950s.

“Quality is nice, but quantity makes a show.”

Photo: Helena Rubinstein

Foundation

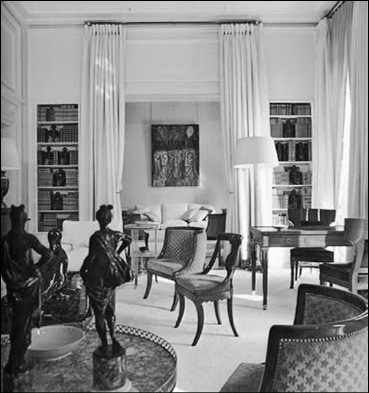

Liliane Bettencourt’s salon in her Neuilly mansion,

a model of tastefulness.

Photo:

Architectural Digest/

Condé

Nast

Family Affairs

I

The sons and grandsons of an industry’s creators

won’t take risks. Sons should inherit money, but not management. If a son wants

to work, he should take a job elsewhere and work his way up.

—E

UGÈNE

S

CHUELLER

,

La

Révolution de l’économie

A

mong the

most strongly held of Eugène Schueller’s many strongly held beliefs was the

conviction that businesses (as opposed to money) should not be passed on as a

family inheritance. When Helena Rubinstein’s first grandchildren were born, she

declared, “Now the business will last for three hundred years!”

1

But such a thought would have been anathema to

Schueller. On the contrary, he thought entrepreneurship required very particular

skills, and that “being a general’s son doesn’t automatically make you a good

general.” (This was a pet expression of Schueller’s, and he used these same

words in article after article, lecture after lecture.)

Of course, it was easy for him to say this. His

only child was a daughter, which (given his view of woman’s place in the world)

ruled her out as a possible candidate. And since he had no siblings, he had no

aspiring nephews. But it also left him with a problem. Building up L’Oréal had

been his life’s work. It would have been less than human, not to say

irresponsible, to give no thought to his eventual successor. Schueller, of all

people, knew that his day-to-day decisions affected the lives of hundreds,

possibly thousands, of people. Since he was not immortal, perhaps the most

important decision of all concerned the man who would take his place when he

died or retired. But who would that be? And how would Schueller identify him? As

the thirties drew on and he moved into his middle fifties, he began, consciously

or subconsciously, to look around for the young man who would become, in effect,

his surrogate son.

As it turned out there would be two such people,

each playing a different filial role.

The first, André Bettencourt, was introduced to

Schueller in 1938 by a journalist friend, who invited Bettencourt to lunch with

“a man you really ought to meet, he’s extraordinary.”

2

Bettencourt was then nineteen, Schueller fifty-seven. The meeting

took place in Schueller’s boulevard Suchet apartment, where Bettencourt also met

Schueller’s daughter, Liliane. The friendship flourished. In December 1941,

Bettencourt referred in an article to “a remarkable book by a friend, M. E.

Schueller, called ‘La Révolution de l’Economie’ . . . that all

businessmen ought to read.”

3

In that same year, 1941, Bettencourt drew

Schueller’s attention to another promising young man: his friend François Dalle.

The two had met as students in 1936, when both lived at a university residence

for young men such as themselves—Catholic, provincial, well-connected—run by the

Marist Fathers at 104, rue de Vaugirard. In 1941, Dalle needed a job, and

Bettencourt thought Schueller might have one for him.

Although Bettencourt and Dalle were both members of

the Catholic bourgeoisie, they had grown up in very disparate milieux. The

Bettencourts were traditional Normandy landowners, conservative and rooted in

their village, St. Maurice d’Ételan, of which André’s father was the mayor, of

which he would in time become mayor himself, and where they were intricately

intermarried with the surrounding seigneurial families. They were pious, and M.

Bettencourt

père

went on frequent religious

retreats, although meditation did not prevent him writing home to remind his

gardeners, when planting new apple trees, to “if possible put some fresh soil in

the holes.”

4

These two preoccupations—religious

and agricultural—were passed on to André, and were reflected in his wartime

activities.

By contrast, the Dalles were industrialists from

France’s gritty Nord. François’s father was a brewer in Wervicq-Sud, near the

Belgian border. The family lived beside the brewery, and their neighbors were

mostly working families. François grew up in an austere and socially conscious

household, aware from his earliest youth of industrial conflict and the ravages

of war. He realized, too, that the main source of unrest in the local textile

industry—the workers’ continuing and justified complaints about their low level

of pay, the factory owners’ riposte that as their profits were so low, they

could not afford to pay more—arose because of outdated attitudes and machinery.

Capitalism, he concluded, could be justified only insofar as it brought material

abundance.

5

By the time the two young men arrived in Paris,

toward the end of 1936, it was clear that Europe was sliding toward another

general conflict, and that France, if involved, would almost certainly be

defeated. In 1937 and again in 1938, Dalle, Bettencourt, and some other friends

from the old university lodgings at 104, rue de Vaugirard, including France’s

future president François Mitterrand, whose family was in the vinegar business

in the Charente, visited Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany during their

vacations. They saw tanks rolling at full speed through villages while the

villagers cheered and girls threw flowers. On one memorable day, on a riverbank

near the German-Luxembourg border, they watched as a thousand soldiers in

swimming-gear stood at attention while a hundred-piece orchestra played

Beethoven, and then, at the sound of a bugle, threw themselves, as one man, into

the river. It was an impressive show of fitness and discipline, and the young

Frenchmen were left wondering how their ragtag conscript army could ever stand

up to a force composed of men such as that.

6

In this charged and uncertain atmosphere, the young

men from 104 inclined to the right. The left seemed to offer only chaos.

Fascism—not as practiced by Hitler, but of the Mussolini and Salazar Catholic

variety—at least held out the possibility of order. “We didn’t think Mussolini

would go in with Hitler,” Dalle said. “We were bourgeois students, Catholics.

. . . We knew the war was lost before it began, because our arms were

as hopeless as our high command. We were just cannon fodder.

. . .”

7

They were mostly studying

law, and preferred to use the faculty library, which was recognized as the

province of the far-right Camelots du Roi, rather than the Sorbonne library,

where, Dalle said, “less than 5 percent were non-Marxists, and not a single girl

ever caught your eye.”

8

When the war came, Dalle, Mitterrand, and

Bettencourt, like all young Frenchmen, were called up. Following the debacle of

France’s capitulation, Mitterrand was captured and sent to a prisoner-of-war

camp inside Germany, an experience that would shape his future political career,

while Bettencourt and Dalle returned to Paris, and looked around for something

to do. Bettencourt found a job in journalism, writing a youth-interest column

under the heading

Ohé les jeunes!

for a magazine

called

La Terre Française

, directed at

agriculturists. Dalle thought of resuming his studies. But his preferred

professors were no longer teaching their courses, and besides, having just

married, he needed to earn some money. Going through the want ads one day he

noticed that the Society of French Soapmakers, working through Monsavon, was

looking for trainees. He knew that Schueller owned Monsavon, and knew and liked

his economic theories. He knew, too, that his friend André was acquainted with

the Schuellers. Bettencourt encouraged him to apply for the job.

Schueller, who always took a personal interest in

trainees, met Dalle, agreed to hire him, and asked where he came from. The Nord,

Dalle replied. “That’s good,” Schueller said. “In this country there are only

two sets of people who really work, the ones from Alsace, and the ones from the

Nord.” A few days later, Dalle presented himself for work at the Monsavon

factory in Clichy, a dank place in what he described as “the miserabilist style

of the Paris suburbs.” He was twenty-four. His job was to help the sales

director’s secretary—“a radical change of direction,” as he observed, “for

someone who had always dreamed of teaching law.”

9

His first job, which he hated, consisted of

multiplying the number of soaps sold by their price, to calculate turnover. But

at the end of 1943 the sales director fell ill, and the managing director

mysteriously vanished: suddenly, at the age of twenty-five, Dalle found himself

the de facto boss of a large factory. Schueller liked to divide his colleagues

into two categories: people men and things men. Dalle certainly wasn’t a “things

man,” though there were two in the factory: they had just devised an innovative

continuous soap-making process that would prove valuable in the immediate

postwar years. However, they couldn’t try it out on Monsavon’s wartime product,

which consisted almost wholly of bentonite and kaolin and contained virtually no

fat. It could hardly be called soap at all. And there were problems with morale.

Keeping Monsavon’s little community going in those desperate days, when food of

any kind was short, good food almost unobtainable, and nobody trusted anyone

else, was an invaluable experience for the “people man” François Dalle would

become.

Monsavon survived the war. But it then faced the

problem of surviving the peace, which had its own difficulties. In wartime the

buying public had grabbed anything put before it, including Monsavon’s ersatz

soap; but now the presence of American troops and American products reminded

battered Europeans of a long-forgotten abundance. American competition meant

hard times for indigenous companies facing huge shortages of raw materials.

Dalle thought for a while about returning to the law, but he had lost the habit

of study, and soon realized that the subject no longer interested him. So he

returned joyfully to Monsavon and the entrepreneurial life he found so

exhilarating, and was put in charge.

During these years, Schueller let Dalle get on with

the job without interference. One summer Sunday in 1948, however, an indication

came that Schueller had plans for him. Summoned to the Franconville house, Dalle

was informed that, starting the next day, he was to work at L’Oréal as well as

Monsavon. He had done well with Monsavon and, hopefully, would continue to do

so. But now it was time to find his place within the company as a whole. “I was

flattered, but terribly embarrassed,” Dalle remembered. “It hadn’t ever crossed

my mind that women’s hair grew white as they got older, let alone that they

might dye it—the notion that one might want to change the natural order of

things would have seemed odd to me, actually almost shocking. Where I came from

women didn’t use cosmetics.”

10

This uncertainty was soon buried, however, beneath

the whirlwind of his new life. He was given an office at rue Royale and began

the long task of getting to know a new business and gaining the trust of

longstanding lieutenants over whose heads he was all too evidently being

promoted. He soon became Schueller’s chief confidant, which meant adopting his

chief’s frenetic pace. From six till eight a.m. he read notes dictated by

Schueller the previous evening, then walked for an hour around the park at

Bagatelle, near where he lived, before dictating his responses. He spent the

morning at Monsavon and the afternoon at L’Oréal, staying there until nine—the

hour when Schueller left the office.

After a few months of this pace he became tired,

and Schueller offered him and his family the L’Arcouest house for a couple of

weeks of relaxation and enjoyment. It rained solidly; when the offer was renewed

the following year, Dalle’s wife and children refused to accompany him. It

rained again; cooped up all alone in the big house, Dalle thought longingly of

Paris and all the work awaiting his return. He called for his secretary and

resumed his Parisian work schedule, wondering later if this had not been a

deliberate ploy on the part of Schueller, who did the same thing during

his

vacations.

It was soon clear to them both that Dalle would be

L’Oréal’s next chief executive. But it was not until 1957, when Schueller’s

health began to fail, that this was said in so many words. That July, Dalle was

summoned to L’Arcouest. He found Schueller tanned and apparently well, but

appearances were deceptive: he was dying. He was L’Oréal’s present, the old man

said, but Dalle would be its future. The speech left both of them in tears. Not

long after it, Schueller died, and Dalle became managing director of

L’Oréal.

Where, politically and

commercially, Schueller had remained essentially a man of the 1930s, Dalle would

move L’Oréal into the postwar world.

11

W

hile

Dalle was taking his place as Schueller’s industrial heir, André Bettencourt had

maintained their friendship on a more personal level: in 1950, he would marry

Schueller’s daughter, Liliane. The file of papers concerning Schueller’s

épuration

trial contains two letters from Bettencourt,

one written in January 1944, the other in September of the same year. They make

it clear that the two had become close enough for Schueller to trust the younger

man with both money and personal confidences.

By 1944, the course of the war had turned in the

Allies’ favor, and those who had positioned themselves three years earlier in

expectation of a German victory now found themselves somewhat awkwardly placed.

Bettencourt had spent the first years of the war as a journalist, writing for

collaborationist and Pétainist publications, and had later spent some time at

Vichy, working for the Pétain administration there. It is clear from his January

letter to Schueller that both of them anticipated difficulties if, as seemed

increasingly likely, the Germans were defeated.