Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (102 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Kevin:

If the traffic gives you so much worry, why not just stay home?

Josh:

You’re gonna miss Neftali!

In the middle of the sixth inning the Rangers video board lights up with red, blue, and green dots that race one another. This is nothing new. The nightly dot race has been part of the Rangers experience since debuting at Arlington Stadium in 1986. But in 2010 the dots took a page out of the Brewers’ book and began extending their race down onto the field. They begin on the video board, and then emerge down the left-field line to race to third base.

In 2011, the Legends Race took the place of the Dot Race on select nights. This innovation features prominent Texans like Sam Houston, Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, and Nolan Ryan portrayed with giant bobbing heads that appear above period-specific costumes. To say these figures are a bit goofy is an understatement.

Josh:

Wow, Nolan must have taken his Advil today. He’s really booking it.

Kevin:

I’m pretty sure that’s not really him.

Josh:

Well, he’s always kind of had a big head …

Kevin:

Dude, the real Nolan Ryan is sitting right by the Rangers dugout.

Josh:

Oh yeah. I forgot.

After “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” in the middle of the seventh, “Cotton-Eyed Joe” blares through the P.A. system. And boy, do the locals ever eat it up.

Josh:

Have you heard the contemporary version by Michelle Shocked?

Kevin:

Umm. No.

Josh:

Well, you oughta.

Kevin:

Do you want to be a music reviewer or a baseball author?

Josh:

Umm, the latter.

Kevin:

Then you’d better keep the musical asides to a minimum.

Despite this late-inning petering out, 2010 did mark the dawning of a new era for not just the Rangers’ team but their fans as well. During the playoff run the whole country became familiar with the local rooters’ “Claws” and “Antlers.” Don’t worry, in the event that you’ve forgotten, we’ll explain.

That Rangers lineup possessed a nice balance of speed and power. On the base paths shortstop Elvis Andrus registered thirty-two swipes while four other Texas starters totaled fourteen or more. And at the bat, Hamilton hit thirty-two dingers to pace a lineup that cranked 162 long balls. To celebrate this multi-dimensionality, as game events dictated, Rangers fans took to flashing a Claw hand-signal, symbolizing force and power, whenever a local son homered, and dual Antler hand-signals above their ears, symbolizing speed.

The unique fan tradition actually began with the players. According to local lore, Esteban German started the Claw when he was playing for the Rangers’ Pacific Coast League affiliate in Oklahoma City in 2009. After he introduced it to the big league team in early 2010, Nelson Cruz and Hamilton started the Antlers. The fans picked up on it and the rest is history.

If you can’t quite figure out how to hold your hands, look for the Deer Cam and Claw Cam on the JumboTron during the eighth inning and the locals will show you how.

Ryan, Texas Ranger

No, Cordell Walker was not the most kickass Texas Ranger of all time. Nor was C.D. Parker. Nolan Ryan was. Yeah, we know this pop-culture reference is a bit dated, but

Walker, Texas Ranger

is still on in syndication, so we say it still works. After all, comparing a baller to a real (well, sort of) ranger as dominant as Walker, is about as high a compliment as we can pay a gun-slinging Texan. Two of Ryan’s most memorable feats came in a Rangers uniform at the end of his career. When the old man threw his final no-no on May 1, 1991, against the Blue Jays, he was forty-four, making him the oldest player ever to turn the trick. His other Texas-sized accomplishment had come two years earlier when he whiffed Oakland’s Rickey Henderson for career strikeout number five thousand on August 22, 1989. The Ryan Express went on to rack up 714 more K’s. His 5,714 is the all-time record and the next-best guy—Randy Johnson, who had 4,875—isn’t even close.

Scan the front row of box seats on the third-base side and you’re apt to spot Cowboy Wayne—a veritable Kenny Rogers look-alike—just beyond the visitors’ dugout. He’ll be wearing a big old cowboy hat, sporting a baseball glove on his left hand, and holding a colossal green fishing net in his right hand. This guy wants a ball.

A season-ticket holder, Wayne has been getting plenty of foul balls in recent years. He started bringing the net to games in 1995 and claims to have scooped up hundreds of balls since then. Don’t worry, as soon as Wayne sees lightning in the sky, he puts the aluminum-framed net under his seat.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Lone Star Ball

www.lonestarball.com/

Lone Star not only covers the Texas scene but the rest of the Majors as well. - Nolan Writin’

http://nolanwritin.com/about/

Great name for a blog and the content gets a Silver Boot too. - Dallas News Rangers Blog

http://rangersblog.dallasnews.com/

If you want the inside-the-clubhouse scoop, the

Dallas News

site is the best place to go.

The Lone Ranger theme song, or “William Tell Overture” as people with class call it, revs up the crowd when the Rangers are trying to mount a late-inning rally.

We Acted Like Star-Struck Kids

When we wrote to the Texas Rangers telling them of our seminal baseball road trip and plans to write a book, we hoped they might send us a pair of tickets to a future game. But the Rangers did us even better. They gave us field-access press credentials for batting practice. Of course, we didn’t know how we were supposed to get onto the field or where we’d be allowed to stand once we got there. So we milled around in the stands for five minutes before Kevin mustered the nerve to ask a security guard how the whole deal worked.

Sports in (and around) the City

Mickey Mantle Boulevard

If you’re on the way from Arlington to Kansas City or Denver, why not drive a few hundred miles out of your way to visit Commerce, Oklahoma, where Mickey Mantle grew up. The Mick was born on October 20, 1931, in Spavinaw, Oklahoma, but his family moved to a modest home in Commerce, a lead and zinc mining outpost, when he was three. His boyhood home is still standing at 319 South Quincy St., but of even greater interest is the statue of Mantle (batting right-handed) that can be found beyond the outfield fence of the youth baseball field on Mickey Mantle Boulevard/Highway 69.

“Not a bad detail to pull,” Kevin said.

“I’ve had worse,” the guard smiled, and with that we were off and running. The guard told us which gate to use and where we were allowed to go. Basically, as long as we stayed in foul territory on the infield, we’d be okay.

The Rangers had already taken their swings and the Oakland A’s were hitting. So we scampered onto the field, trying to look cool, like we’d done this a thousand times before. We stood behind the cage and rubbed elbows with Jermaine Dye and Terrence Long, while Miguel Tejada raked.

We stared in amazement at each hitter, like we’d never watched anyone hit a baseball before. Man, did the ball jump off those bats. And standing that close, the pitches, considered “meat” to the big leaguers, looked pretty fast to us.

Josh spent most of his time trying to pilfer a ball.

“Will you knock it off?” said Kevin.

“What?” Josh asked.

“It’s pretty obvious you have a ball in each pocket. And do you think it looks professional to be resting your foot on a ball?”

“Well,” Josh said, “those cut-off shorts you’re wearing don’t exactly make us look professional either.”

“True enough,” Kevin admitted.

“So I’m getting myself another ball.”

Just as Josh was bending over to pocket another Rawlings, the Rangers manager at the time, Buck Showalter, came bounding up the dugout steps and gave him a look of consternation. Nervous and attempting to recover his dignity, Josh tossed the ball toward the mound and snapped into reporter mode, asking Buck if he could have a few minutes.

“Sure,” Buck said.

“What are your favorite ballparks?” Josh asked.

“Yankee Stadium’s at the top of the list,” Buck said. “I also like Baltimore a lot.” He paused, then said, smiling, “And I like the ballpark here in Texas. Wrigley Field … Fenway … I coached at the old Comiskey. I’ll tell you the one I really like—I’ve broadcast from the new ballpark in Pittsburgh, and I think that’s a new park that will really stand the test of time.”

The dubious start aside, the interview was a real thrill for Josh, as was being down on the field for both of us. And for the record, Josh’s final till was four balls, which he called “a fair day’s work.”

COLORADO ROCKIES,

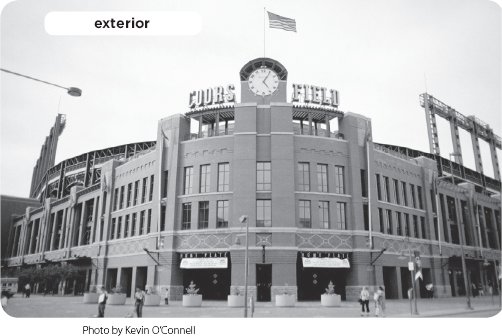

COLORADO ROCKIES,COORS FIELD

A Rocky Mountain High

D

ENVER

, C

OLORADO

605 MILES TO KANSAS CITY

820 MILES TO PHOENIX

850 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

915 MILES TO MINNEAPOLIS

T

he Rocky Mountains, which rise beyond Coors Field’s left and center-field walls, provide as spectacular a backdrop for a ballgame as travelers will find in this great wide land of ours. As the sun sinks behind the snow-capped peaks, an orange glow illuminates baseball’s magical twilight hour. There may be no more beautiful setting in American sports. With this breathtaking view well worth the cost of admission on its own, fans at Coors Field receive the additional treat of getting to watch a baseball game. And not just any game. At Coors, fans are practically guaranteed a highly entertaining game, full of offense. Sure, the once gaudy homer totals for which the park was originally known have declined somewhat thanks to the introduction of a ball-soaking humidor hidden within the bowels of the stadium, but rest assured, runs will be scored, often and in bunches, when you’re in town. And no lead will be safe until the final out. This is mile-high baseball we’re talking about, where long flies morph into home runs, where the curve ball flattens out, and where the deeper than usual outfield fences result in gaps that leave enough room for a skilled pilot to land a 727 between the outfielders. For the record, the ballpark measures 424 feet to right-center, 415 to straightaway center, and 390 to left-center. Even the foul poles—350 feet away in right and 347 in left—are distant.

Despite its enormity, Coors feels like a ballpark, and not a stadium. And it’s a good thing, because Coors represents an important link in ballpark evolution. At the time of its debut in 1995, it was the first new National League ballpark to open since Montreal’s Olympic Stadium in 1977, and the first baseball-only facility to be unveiled in the Senior Circuit since Dodger Stadium in 1962. Coors appeared on the MLB landscape a year after the Indians and Rangers opened their new yards in the American League, and two years before the Braves would open Turner Field. From the very start, Coors has fit well in its retro-classic lineage, blending into its warehouse district neighborhood with an attractive facade made of Colorado limestone at street level and red brick upstairs. If any ballpark has the right to feature red rock in its construction, it’s this fine field in Colorado, which is flush with red rock formations. Colorado, you may recall, was once part of Mexico and its name, in Spanish, means “colored red.”

Kevin:

So you aced high school Spanish and you’re still showing off?

Josh:

Actually Mr. Bonczeck gave me a C+.

Kevin:

The bastard!

Josh:

Yeah. ¿Who’s laughing now, Señor Bonczeck?

As fans soon discovered upon Coors’ opening, the altitude at which the park is set not only gives road trippers

who may be unaccustomed to the thin air “wicked bad” ice cream headaches, only without the ice cream, but also turns ordinary-appearing fly balls into home runs and ordinary-appearing home runs into massive feats of earth-shattering strength. It didn’t take long for the Rockies’ fans and players to realize this and to develop a liking (well, the hitters anyway) for this special breed of hardball. After the expansion Rockies spent their first two seasons at Mile High Stadium, the first game at Coors took place on April 26, 1995. Appropriately, the Rockies and Mets combined to hang twenty runs on the scoreboard, with the home team prevailing 11–9 in fourteen innings. And that was just the beginning. In 1996, the Rockies and their opponents set a new Major League record, smacking 271 dingers in eighty-one games at Coors. The previous record of 248 had been established at Wrigley Field of Los Angeles, where the expansion Angels played in 1961 before moving temporarily to Dodger Stadium, and then, ultimately, to Anaheim Stadium. But the Rockies and their opponents weren’t done yet. With the Steroid Era in full swing and the air oh so thin in Denver, the new record fell in 1999. That year, Coors rooters witnessed a whopping 303 home runs or, to put that in perspective, 3.79 long balls per game. In comparison, the Rockies and their opponents hit just 157 home runs in the Rockies’ eighty-one road games that season, or 1.92 per game.

It came as no surprise then, when the 1998 All-Star Game took place at Coors—during the so-called “Year of the Home Run”—and the two teams combined for a Midsummer Classic record of 21 runs. The American League prevailed, posting a 13-8 W behind an MVP performance from Roberto Alomar, after Robby’s older brother, Sandy, had won the trophy the previous summer.

Josh:

For the record, the game featured about fifty guys we suspect of PED use.

Kevin:

But our publisher won’t let us print their names.

Josh:

Probably a wise call. The last thing we need is for Roger Clemens or Barry Bonds to sue us for character defamation.

Kevin:

Agreed. That would be bad.

As the nightly installments of home run derby continued, it didn’t take long for people to realize Coors was a launching pad. Hence, the park’s “Coors Canaveral” nickname in its early years. Remarkably, though, before big league ball arrived in Denver, no one had worried much about the effects of the city’s elevation on the game. No one, that is, but original Rockies manager Don Baylor. When the hulking skipper suggested that special high-altitude balls might be needed for games in Denver, his words of wisdom were fluffed off. After seven years of double-figure run totals, the doubters were finally ready to listen in 2002, though, and the league approved the Rockies’ request to bend the rules a bit. That year, the equipment staff started storing its boxes of official game balls in a humidor at 40 percent humidity in the hopes that the soggy balls (which are imperceptibly heavier and drier on the exterior) wouldn’t fly as far. There was only a slight drop-off in homers, but according to our sources several members of the home team smoked exceptionally dank stogies all season long. The fact is, they could soak the Rockies’ game balls in tar and vinegar and they’d still be flying out of Coors. In 2010, for example, the Rockies and their opponents combined for 1.496 home runs per game, which was second only to the dingers surrendered at U.S. Cellular Field to the White Sox and their opponents. The “Cell” gave it up to the tune of 1.545 long balls per game, but keep in mind, it is an American League park and faced a season-long assault by designated hitters unlike Coors. So even if it’s not off-the-charts homer-happy anymore, it’s still safe to say Coors is a homer haven.

But it isn’t just the prevalence of home runs that makes Coors a graveyard to once promising pitching careers. Yes, a batted ball that travels four hundred feet at sea level will carry 5 to 10 percent farther (420 or 440 feet) a mile above sea level. But more than just that, breaking balls don’t break as sharply in the lower-density air, enabling Coors batters to tee off on curveballs and sliders that might otherwise elude the fat part of their bat. To make matters worse, line drives shoot up those wide Coors outfield gaps, forcing outfielders to play a step deeper at Coors than they ordinarily would. This means even poorly struck bloopers are more apt to fall in for hits between the infielders and distant outfielders.

As a result, the Colorado club perennially ranks near the top of the NL in runs scored and near the bottom in runs prevented. These trends affect the Rockies’ ability to compete financially with other teams in two ways. First, the Rockies must overpay to lure qualified free-agent pitchers to Colorado. Second, they must overpay their own offensive stars who expect big contracts after putting up inflated stats that are the product of playing eighty-one games per season in Denver.

The thin air has also affected the way fantasy baseball owners across the country manage their squads. Savvy owners (read: super-nerdy like Josh) never draft Rockies pitchers, but load up on Rockies hitters. Once the season begins, the objective is to bench any pitcher on your roster whose team is heading into a series at Coors, and activate any batter whose team is playing in Denver. Even when Tim

Lincecum—the staff ace of Josh’s Ultimate Baseballers—is scheduled to pitch at Coors, Josh gives him a night off. It’s just too much of a ratio stat risk to let even “the Freak” pitch in Lando Calrissian’s “Cloud City.”

Kevin:

Nice old-school

Star Wars

reference.

Josh:

I always liked Lando. He’s one of the few Armenians who have been to outer space.

Kevin:

What about NASA’s James Philip Bagian?

Josh:

Good Lord you can be infuriating.

But never mind the fantasy baseball and

Star Wars

banter. Besides sogging their balls, we challenged ourselves to wonder, how else could the Rockies compensate for the thin air? A natural reaction at first blush might be to move back the fences still farther from the plate, but that would force outfielders to play even deeper, which would result in even more dying quail singles and stretch doubles. Home run stats would decline, but batting averages and runs per game would not.

Josh suggests growing the infield grass four inches high to turn potential ground ball singles into ground outs. Another brilliant Josh idea is to add ten feet in height to the outfield fences by installing see-through Homer-Domestyle Plexiglas extensions to the wall tops. These shields would turn some of those fly ball homers into long doubles.

Kevin thinks the Rockies should take away the first few rows of seats down at field level to enlarge the already expansive foul territory and increase the number of foul pops. He also thinks batters should have to put their noses on their bat handles and spin around three times before stepping into the batter’s box to hit.

No doubt, balls would still fly out of Coors, but with these modifications we think pitchers would have more of a fighting chance. In the meantime, the Rockies should teach every pitcher in their player development system how to throw a forkball/splitter before they reach “the Show.” After all, the first pitcher to throw a no-hitter at Coors was Hideo Nomo, master of the splitter, who turned the trick September 17, 1996, pitching for the Dodgers.

To put in perspective how altitudinous Coors Field is, consider that prior to the arrival of Major League Baseball in Denver, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium held the distinction of being the loftiest yard in the bigs at one thousand feet above sea level. Coors is 5,259 feet above the waves, and that’s after you subtract twenty-one feet because the playing field is below the street outside. A row of purple seats amid the otherwise green seats of the upper deck—Row 20—marks the mile-high plateau. We know what you’re thinking, and the answer is “no.” The ballpark is too well populated to ever consider joining the “mile-high club” in its stands, no matter how cute and/or adventurous your partner may be.

Speaking of big crowds, Coors welcomed 49,983 fans through its gates for the first World Series game ever played in Denver on October 27, 2007. And the ballpark lived up to its billing as an ERA killer. The Red Sox and Rockies banged out twenty-six hits and combined for fifteen runs. After that 10-5 Red Sox win, however, the Red Sox posted a more modest 4-3 victory in Game 4 to sweep the upstart Rockies, who had won twenty-one of twenty-two games down the stretch, including a one-game playoff with the Padres to decide the NL Wild Card.

Despite bowing in the October Classic, that magical summer of 2007 represented a glorious coming of age moment for Denver as a baseball city. It had been a long time, and a lot of hard work, in coming. After Major League Baseball announced Denver was one of six cities being considered for an expansion franchise, city voters passed a .1 percent sales tax increase in 1990 to finance construction of a new ballpark, in the event MLB awarded the city a team. The other expansion sites under consideration were Buffalo, Orlando, Washington, D.C., Tampa/St. Petersburg, and Miami.