Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (106 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

If you travel to Denver via road or rail, chances are your body will gradually acclimate itself to the altitude as you weave your way through the mountains. But those arriving by plane should beware: Sudden immersion in the thin air can cause dizziness, nausea and extreme ass fatigue. This is no joke. We repeat, pay attention before setting out to run a pregame 5 K. The air in this town contains less oxygen than the air back home. As a result, you’ll find yourself panting like a schoolboy on prom night if you break into anything more than a slow saunter on your way into the ballpark. And all of that respiration can lead to a case of dehydration. Drinking alcohol only compounds the effect, as beer consumed at high altitude affects you more than usual.

Josh:

We won’t even try to tell you how to adjust any baking recipes you may attempt while in town. But trust us, your times and temps will be all messed up.

Kevin:

Are you serious? Do you really think our readers are going to make Toll House Cookies at their hotels?

Josh:

You were the first to complain when my bundt cake didn’t rise.

Kevin:

Fair enough.

To counteract these effects, be sure to drink plenty of water before and after arriving in Denver. If, like Josh, you fly into town two hours before first pitch with already low H2O levels, drive straight to the ballpark, and then spend an hour dragging your butt up and down the aisles of the upper

deck to scope out the sight lines for your readers, don’t be surprised if you wind up retching in the Coors Field men’s room.

Kevin:

That’s a nice image. I’m sure our readers will appreciate it.

Josh:

Want some more oysters, funny man?

On hot days, ballpark staffers dressed in purple wander the lower level stands equipped with water tanks on their backs. As fans cheer, these men and women hydrate the masses with wide streams of cold water. It’s not quite the outdoor shower fans enjoy on Chicago’s South Side, but it’s not bad. And when you consider that most of the young women in Denver keep in excellent shape by hiking, rock climbing, and mountain biking, well, it’s even better. We say, soak ‘em good!

When the Rockies are one inning from victory, the ballpark tune-meister cues up Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way” on the PA and plays the first few power chords to rev up the crowd. Another chord plays to celebrate each subsequent out, then, when the final out is recorded, the song begins in full force.

Stick around for a minute and listen for the baseball reference in the later verses, when the crooner sings, “the bases are loaded and Casey’s at bat …”

Cyber Super-Fans

- The Purple Row

www.purplerow.com/ - The Rockies Review

www.rockiesreview.com/ - Heaven and Helton

http://heavenandhelton.blogspot.com/

Sports in the City

Colorado Silver Bullets

In 1994 an all-female professional baseball team called the Colorado Silver Bullets took the field for the first time. Led by Hall of Fame skipper Phil Niekro, the team was formed to expand hardball opportunities for women of all ages by demonstrating that ladies could more than hold their own on a regulation diamond with a little white ball, and not just on a little diamond with an oversized white ball.

The Bullets originated in Knoxville, Tennessee, but when the Coors Brewing Company agreed to sponsor them on behalf of the Coors Light brand, they moved to Colorado.

Barnstorming across the country, the Bullet Girls made national headlines playing minor league, semipro, and collegiate men’s teams. They went 6–38 in their inaugural campaign, playing in Major League facilities like San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, the Oakland Coliseum, the Seattle Kingdome, and Mile High Stadium.

Kevin:

An argument could be made that none of those were actual “Major League” stadiums, at least not according to how that term is currently defined.

Josh:

Harsh words. And from a Mariners’ fan no less.

The Bullets improved steadily over the ensuing four seasons before disbanding in 1998 when Coors, which had spent more than $3 million to back them, opted not to extend its sponsorship. There’s no denying, however, that the Bullets pried the door open just a little wider for women who wanted to play hardball at a high level. Two of their alumnae, Lee Anne Ketcham and Julie Croteau, went on to play for the Maui Stingrays of the Hawaiian Winter Baseball League, and in 1997, Ila Borders, a left-handed pitcher who had posted a 4–5 record at Whittier College, became the first woman to pitch in a men’s professional game when she appeared for the independent league St. Paul Saints.

Kevin:

One of these days a female knuckle-baller is going to come along and blaze a path to the big leagues.

Josh:

It could happen sooner than you think.

Kevin:

I’ve got two little girls at home I could teach to throw the knuckler. Maeve and Rory, dad has a new plan for a college scholarship!

Coors Field has appeared in two episodes of the hit Comedy Central cartoon

South Park

. The show is set, of course, in the fictional town of South Park, Colorado, which is reportedly based on the real-life town of Fairplay, Colorado, a community of approximately 600 people, located 85 miles southwest of Denver. Coors Field’s first appearance was in a 2002 episode entitled “Professor Chaos.” In that episode, the boys take one of their new friends to a Rockies game and he commits the rather large faux pas of ordering tea and crumpets. Three years later, the gang returned to Coors in “The Losing Edge,” which portrayed their

Bad-News-Bears

-style Little League squad advancing to the regional tournament in Denver. The boys were overjoyed when they lost, because that meant they wouldn’t have to waste their entire summer

vacation playing in the national Little League tournament. Unfortunately, though, Kenny was killed during the filming of the latter episode.

Behind the bullpens on the first level is the Coors Field Interactive Area. Whether tee-ball is your thing, video batting cages, or speed pitch, this is a great place to work out some of that excess energy you’ve accumulated during all those hours riding in the car. Just remember what we said about the thin air, though, and don’t overdo it.

The Interactive Area also houses a Fantasy Broadcast Booth where fans can record themselves doing play-by-play for a half-inning while the game is in progress.

Josh:

This is easy enough to do at home. Just turn down the volume on the tube, press the little red button on your microcassette recorder, and start yapping.

Kevin:

Actually, I’m pretty sure there’s a smartphone app for that nowadays. You’re the only person I know who still uses a microcassette recorder.

Josh:

I was wondering why I can’t find fresh tapes at Staples anymore.

Kevin:

I think they file them with the 8-tracks in back.

Whenever a fan catches a foul ball or home run, a ballpark staffer presents them with a special Rockies pin commemorating the accomplishment. Batting practice grabs don’t count, nor do catches made after the ball bounces off another fan, an umbrella, railing or seat.

We Committed an Embarrassing Breach of Clubhouse Etiquette

Prior to visiting Coors Field for the first time in 2003, the greatest thrill of our seminal trip had been watching batting practice in Arlington while standing on the field, donning press passes. The Rangers had granted us field access, something none of the other teams had been willing to do, and we responded by respectfully watching the A’s and Rangers take BP, while being careful not to create any scenes.

A few weeks later, the Rockies did us one better. Not only did Colorado grant us pregame field access, but the team (foolishly?) granted us clubhouse access as well. And boy, did we ever drop the ball.

Giddy as Shriners at a Fredericks of Hollywood convention, we wandered wide-eyed down the Club House Level corridors beneath the stands before the game. We were about to set foot into a big league clubhouse for the first time and we had no idea what to expect.

“Who was that who just walked past?” Kevin asked Josh in a whisper.

“Art Howe,” Josh responded.

“The Rockies are playing the Mets?” Kevin asked.

“Yes,” Josh said tersely. Eager to have the limelight all to himself, Josh was a bit peeved to have to share this special moment in his life with anyone—even his good friend Kevin. His good friend Kevin who had arrived at the ballpark wearing blue jeans and a three-day-old five-o’clock shadow.

“Just be cool,” Josh muttered.

“I am cool. I’m always cool,” Kevin said. “If anything … I’m cool.”

“Right,” Josh said. “Just follow my lead.”

“Whatever, boss.”

The next thing we knew we were standing inside the Mets clubhouse. A reporter talked to Roberto Alomar in a far corner of the room. A TV hanging in the center of the room was showing the Yankees game. Half-empty pizza boxes littered a buffet table at the front of the room—demystifying the clubhouse in our eyes to some degree.

Other than Alomar and Mo Vaughn, all of the other players were out on the field taking batting practice. We looked around for a moment, fingering the “Working Press” credentials hanging from our necks and pretending we belonged there. Then we exchanged glances and headed for the door. And then it happened. Into the room walked Tom Glavine. He breezed past the two of us without a word. Kevin continued toward the door, but Josh froze and then did an about-face. He watched as the ace pitcher took off his practice jersey and rolled his shoulders a few times. It occurred to Josh that for a Cy Young Award winner, Glavine had a bit of a pot-belly and somewhat flabby lats. In any case—emboldened by the successful interview he had conducted with Buck Showalter in Texas—Josh moved in for the kill. Questions percolated in his mind. First he would ask Tom to talk about his favorite ballparks, then he would ask him to explain his role as the Players Union Representative during the work stoppage of 1994. Then he would ask the lefty if he regretted leaving the Braves.

“Um … Mr. Glavine … er … Tom,” Josh said. “Umm … can my friend … er … colleague Kevin and I have a word with you?”

Half naked, Tom turned and looked at Josh somewhat disparagingly. “Not now, dude,” he said. “I’m pitching today.” With that, he turned back to face his locker.

We high-tailed it out of the clubhouse with our tails between our legs and found our way to the cheap seats in left field as quickly as possible. That was where we belonged, sitting among the riff-raff far from the field and even farther from the players.

“How could I have known he was pitching today?” Josh lamented later as the game was about to begin.

“He was the only pitcher in the clubhouse,” Kevin said. “That might have tipped you off. He was also changing out of his practice jersey and putting on his game jersey while all the other pitchers were in the field shagging batting practice flies. Or you could have bought a newspaper before the game and checked to see who was pitching. Or you could have watched

SportsCenter

or logged onto ESPN.com.”

“But what were the odds?” Josh continued.

“Oh, given the prevalence of the five-man rotation, I’d say about one in five,” Kevin said, chuckling.

“I know I was out of line,” Josh said, “but I still hope he gets waxed by the Rockies tonight. I’d like to see him really get his clock cleaned.”

“What?” asked Kevin. “We were the ones at fault here, not him.”

“Doesn’t matter,” said Josh wryly. “I still hope he gets shelled.”

Predictably, Glavine did fine. The Mets jumped out to a 7-0 lead and appeared to be cruising toward a win. The lefthander departed after allowing just one runner to cross the plate in six-plus innings. But the Rockies hammered the New York bullpen for four runs in the seventh inning and five more in the eighth to claim a pretty exciting 9-8 victory in a typical twenty-eight-hit Coors Field slugfest.

“A tough-luck no-decision for flabby-Glavvy is good enough for me,” Josh chuckled on his way out of Coors Field afterwards.

“Yeah, me too,” Kevin said. Then after a pause he added, “Hey, here’s an idea. How about tomorrow you follow my lead instead of the other way around like we worked it today?”

“Will your lead take us anywhere near the clubhouse?” Josh asked.

“No way,” Kevin said. “I was thinking we’d spend a day up in the Rockpile.”

“Sounds good,” Josh said.

And that was the last time either of us set foot inside a big league clubhouse.

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS,

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS,CHASE FIELD

A Baseball Oasis in the Valley of the Sun

P

HOENIX

, A

RIZONA

355 MILES TO SAN DIEGO

355 MILES TO ANAHEIM

375 MILES TO LOS ANGELES

820 MILES TO DENVER

T

he climate in Phoenix is just right for baseball in March. And it’s not too bad in November. But from May through October, the players would sweat like pigs, the fans would get heatstroke, and the grass would burn down to its roots by the completion of the third inning if they ever tried to play then. But after years of having their baseball appetites whetted by the Spring Training games their state hosts, Arizonans wanted a regular season team. One solution would have been to build a dome. But by the time the bug to plant a regular season baseball flag in Phoenix had taken hold of the Phoenix area fans, politicians and business leaders, the American people had clearly soured on watching their National Pastime be played on a plastic rug. For a time, though, it must have seemed as if the good people of Arizona had a choice to make between three alternatives, none of which was perfect. Either they could build an outdoor stadium and set up a triage center on the premises for the purpose of diagnosing all of the heat-related maladies the players and fans would suffer, they could build a shiny new dome complete with a fluorescent green carpet, or they could just content themselves to get their baseball fix in the spring, during Cactus League play, and in the autumn, when the Arizona Fall League brought the game’s best prospects to the area. That was the conventional wisdom. But “cooler” heads eventually prevailed, and the so-called experts were proven wrong by Chase Field. Thanks to the stadium’s retractable roof and massive air conditioners summer baseball is not just possible but quite enjoyable in Phoenix. And the natural grass, which gets all the sunshine it needs when the roof is open in the hours before game time, is as plush and thick as any in the league.

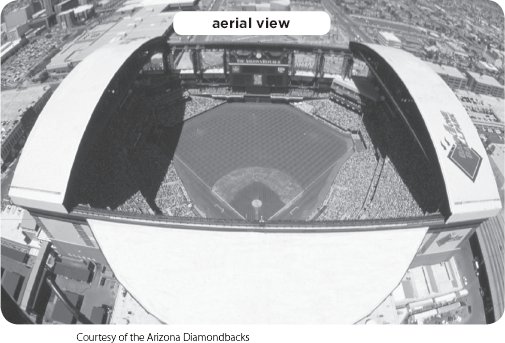

From the exterior, Chase Field does not appear to be a baseball haven. It looks more like an oversized aircraft hangar. The roof, whether open or closed, dominates the design. The two ends of the open roof move toward the middle to close as each side consists of three telescoping panels that can be operated independently or in unison. That’s nine million pounds of steel up there, enough to cover nearly twenty-two acres. At ground level the brick and steel attempt to capture the retro-warehouse look of other new ballparks, but because the roof rises so very high—two hundred feet—the supportive structure above the brick kind of overshadows the intended effect. These huge panels of white and green give the park its hangar look. Chase Field conjures not baseball’s antique parks of yore, but rather makes a bold statement about man’s—or, rather fans’—ingenuity and determination in rising up to meet the challenges posed by the blistering desert sun. Closer to ground-level, both baseball fans and the local power grid benefit from a visually appealing expanse of solar panels. This unique awning shades the entry plaza and ticket booths while harnessing the sun’s rays into useable clean energy.

When the roof is closed Chase Field presents the controlled environment of a dome despite its natural grass surface. Having grown up watching baseball in the Kingdome, Kevin swears indoor ball has a certain smell to it that he detected a whiff of at Chase. The closed roof creates darkness where there should be light and ensconces those inside with a staleness that so many of the other retractable roof stadiums—such as the ones in Seattle, Milwaukee, and Houston—have overcome. The outfield windows common at other “convertible parks” are present in Phoenix, but they are smaller than the bays at other such facilities. Instead, Chase has large advertising billboards across the outfield where there should have been more glass. When the roof is on and the billboards are in closed position, it feels more like a domed stadium than it would have if these billboards were windows instead. When the roof is opened, however, the atmosphere improves considerably. Late-day sun tickles the grass and reveals the patterns of the grounds crew’s last sweep across the infield dirt. We don’t say this all as mere

criticism, though. We allow that serious alteration of the environment is a necessity in these parts during the late spring and summer months. At the time Phoenix built its giant transformer the only pre-existent retractable roof stadium was SkyDome (soon to be renamed Rogers Centre) and by that measure, the crafty desert folk certainly excelled with their Bank One Ballpark (soon to be renamed Chase Field). We also applaud the Diamondbacks for opening the roof each day to keep the grass alive and to let some fresh air in, and for making a priority of opening it whenever possible at game time. Unlike in Toronto, where fans sometimes sit beneath the big-top while it’s sunny but, perhaps, a wee cool outside, the Phoenicians make every effort to play beneath the stars.

Chase is the most spacious of the retractable-roof yards and it feels that way. As far as manufactured character goes, there’s a swimming pool in right-center, which is an apropos trademark in this land where keeping cool is imperative to one’s survival. Most of the seats are between the foul poles, but they tend to feel far from the action. A “close” seat at Chase, between the bases on the first level, for example, does not feel right in the game. Perhaps this is due to the wealth of foul territory. But there are many innovations in this bold park to celebrate. Before Chase, it was considered impossible to grow grass within a “domed” facility. Now, it’s a common practice. Without Chase, the game may have never seen the construction of even more successful retractable roof parks in Seattle, Houston and Milwaukee where the boys of summer play on natural grass while the respective lids safeguard the field and stands from intemperate weather of another kind.

The folks who designed Chase didn’t listen to naysayers telling them what could and could not be done. They went ahead and did what was necessary. But how? One secret to their success is that the retractable roof is kept open as long as possible each day to let as much sunlight as possible hit the lawn. After some experimentation with Anza, Kentucky bluegrass, and some shade-loving mixes ordinarily unfamiliar to Arizona, where the state flag is a big burning sun, the Diamondbacks settled on Bull’s Eye Bermuda. The turf gets as much sunlight as possible without overheating the stadium. The dual-action panels of the roof can be opened in a variety of manners to put the most direct sunlight on the grass without raising the temperature of the concrete and steel around the field.

Three hours before fans arrive, the roof can be closed and the AC cranked so that by the time the rooters settle into their seats it’s 30 degrees cooler inside. In a city where the average daytime high is 93 degrees in May, 103 in June, 105 in July, 103 in August, and 99 in September, AC is not a luxury, it’s a necessity. Contrary to popular belief, the entire ballpark doesn’t fill with cool air. Because hot air rises and gets trapped up near the roof, it is only necessary to cool the air at the lower levels. An eight-thousand-ton cooling system makes use of an enormous cooling tower located on the south side of the ballpark. Then air handlers push 1.2 million cubic feet per minute of cool air past air coils containing water chilled to 48 degrees. The cool air is forced down where it is needed by the layers of progressively warmer air trapped under the roof.

Kevin:

Warm on top, cool on bottom? Sounds like the recipe for a tornado to me.

Josh:

Sounds like an upside down Brownie Sundae dessert to me.

While sometimes “new” baseball cities must wait for the locals to warm up to the ways of the big league game, this was not the case in Arizona. The game had an avid following in these parts long before the debut of the expansion Diamondbacks in 1998. Since the 1940s big league teams—particularly those from the West Coast—had made their Spring Training camps in the Valley of the Sun. Through the years, Phoenix failed to draw much more than a sniff of interest from the other owners when talk

turned to possible regular season expansion sites, though, due to the summer heat. But with the advent of the moveable roof, it became clear that a sustainable facility could be built in Phoenix. To design an indoor structure, perhaps it is best to go with someone who is familiar with such facilities. The architectural firm chosen for this massive undertaking was Ellerbe Becket from Minneapolis, best known for Boston’s TD Banknorth Garden, Portland’s Rose Garden, and New York’s famous Madison Square Garden. The official cost of the Phoenix ballpark was $349 million, though some estimates that account for cost overruns tack on an additional $55 to $60 million. The residents of Maricopa County funded $238 million of the project with a quarter-cent sales tax increase, and are thus the owners of the building, which is leased to the Diamondbacks. The remaining $111 million came from the Diamondback ownership, with $2.2 million per season coming originally from Bank One for the naming rights. When the ballpark opened its official name—Bank One Ballpark—lent itself to the acronym “The BOB.” With the merger of Bank One and Chase, however, it was renamed Chase Field on September 23, 2005.

In anticipation of the Diamondbacks’ arrival, construction on the ambitious facility had begun in 1995. With the official Grand Opening scheduled to take place on March 31, 1998, the field enjoyed the benefit of a dress rehearsal on March 29, when 49,198 fans turned out to watch the White Sox defeat the Diamondbacks 3-0 in the final Cactus League game of the spring season. After losing that trial run, the Diamondbacks lost the official opener to the Rockies 9-2. The Diamondbacks lost their next four home games too before finally posting a W. Andy Benes, the same pitcher who had lost the franchise opener a week earlier, registered the first win in team history when Arizona beat San Francisco 3-2 on April 5, 1998.

To say that the Diamondbacks enjoyed more than their fair share of success as a still-fledgling franchise would be an understatement. After their first expansion season resulted in a typical 65-97 record, they remarkably won 100 games and the NL West crown in just their second year of existence. After falling to the Mets in the NL Division Series, they were right back in the playoffs two years later, beating the Yankees, of all teams, in a dramatic seven-game World Series. Fans in these parts will never forget the early contributions that veteran players like Randy Johnson, Curt Schilling, Matt Williams, Steve Finley, Jay Bell, and Luis Gonzalez made to the city’s baseball fortunes.

Josh:

How many years did it take your Mariners to have a hundred-win season?

Kevin:

Last I checked your Red Sox haven’t had one since 1946.

Josh:

But we’ve won two world championships since then.

Before Schilling would play a role in the Red Sox’ 2004 World Series run, he was integral to the Diamondbacks amazing 2001 season and post-season. He joined the team that spring and, paired with Johnson, gave Arizona a devastating “one-two punch.” Schilling became the first twenty-game winner in D-Backs history, while Johnson kept striking out batters and maintaining an ERA lower than a snake in a wagon rut.

The 2001 NLDS matched Arizona against the St. Louis Cardinals, and the series went the full five. Next, the Diamondbacks dispatched the perennially “post-season challenged” Braves of Bobby Cox in a five-game NLCS. The young upstarts, only in their fourth season, were now ready to take on the dreaded Yanks, who just happened to be gunning for their fourth consecutive World Championship. The D-Backs took the first two games at home, the second in a masterful three-hit complete game by Johnson that saw eleven Yankees go down swinging. When the Series returned to New York, the Yanks rallied (as they always seem to) winning three in a row to take a 3–2 Series lead. A New York Four-Peat appeared imminent.

As so often turns out to be the case, Game 6 of the World Series was the pivotal game. Returning home gave the Rattlers back their venom, and they bit hard, pounding the Yankees 15-2. But instead of rolling over and dying, as many losers of Game 6 do, the Yanks took charge early in the finale. They carried a 2-1 lead into the bottom of the ninth, in fact, and then sent nearly unhittable closer Mariano Rivera to the mound to put the final nail in the Diamondbacks’ proverbial coffin. The brash New Yorkers thought—strike that—they

knew

the Series was in the bag. Everyone in America seemed to know. After all, wasn’t that the way it always went for the Yankees?