Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (27 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

On a hot night, nothing beats a

water ice

… or two … or three. The Original Philly Water Ice has a variety of fruit-flavored deliciousness that is sure to cool you down on even the doggiest of hot and humid summer dog days.

The generic offerings at the South Philly Markets do not do service to the great food options in the city of Philly. You can do much better. Having said that, we recommend their

vegan dog, black bean burger

, and

vegan chicken sandwich

if you are indeed a vegan. Also, good vegetarian fare is the eggplant-mozzarella-roasted-red-pepper-sun-dried-tomato wrap from

Planet Hoagie

. These offerings have garnered CBP the much-coveted “best vegan food options in MLB” moniker from PETA. But we really wouldn’t recommend becoming a vegan to try them, as there are so many delicious meaty options in the park.

Franklin Square Pizza was disappointing, as ballpark pizza almost always is. Maybe the conditions for piping hot ’za simply cannot be duplicated inside the ballpark, but you can do much better than this thick-crust option at Citizens. The other option to avoid at this ballpark is the regular cheesesteaks they serve at the Cobblestone Grill stands. It’s not that they’re all that bad, but the other options are simply better. If you can’t bear to wait in the line at Tony Luke’s, try Campo’s. Both are superior to Cobblestone’s steaks.

We loved Harry Kalas, but this ballpark restaurant should be avoided, because the service and quality of food are simply too inconsistent. If you like the restaurant-in-the-ballpark idea, you may well enjoy Harry’s, as you can buy tickets to the special seating sections and get a coupon for food in the double-decked restaurant. And it is one of the two places in the park where you can get the Schmitter. But what seems to happen in all these places is that service is slow, the food is mostly mediocre and expensive, and you can always do so much better outside on the concourse.

The Brewery Town has the largest selection (outside of the ballpark pubs) of bottled beers, micros, and imports that they pour from bottles into cups for you.

We spent more time at this air-conditioned ballpark pub than we might usually because our friend and Philly guide Dave was feeling uncharacteristically green around the gills from the previous night’s exploits. It was empty when we walked in at the beginning of the game, but as the heat wore on, more and more fans sought out the air conditioning and bar service. Dave, for his part, sipped ice water and eventually felt a bit more like his old self.

Folks in this town are known for being rabid sports fans. And by rabid, we mean frothing at the mouth. They cheer wildly when their team does well and boo lustily when hometown players don’t meet expectations. The fans are every bit as diehard as the Red Bird fanatics in St. Louis, only much more sardonic and short-tempered. Chalk it up as an East Coast phenomenon, as the fans in Boston and New York are just as unforgiving. In any case, the game-day atmosphere at CBP is festive and electric nearly every night. During the game we attended a fan in the second deck dropped a foul hit to her and was booed as if she’d struck out in Game 7 of the World Series. It’s just that way in Philly, you’re either a hero or goat, with little room for mediocrity in between.

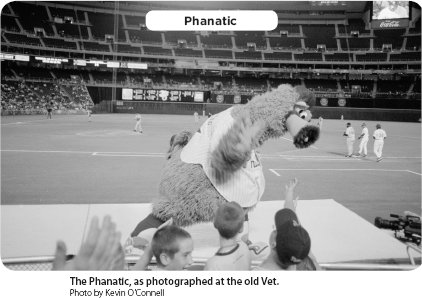

Hailing from the Galapagos Islands, this six-phoot six-inch, slightly phat, pheathery green phellow with the nose like a megaphone keeps Phills phans entertained all game long. His clowning has inspired the antics of other mascots across the nation. He’s traveled the world and has appeared on many other television shows as well.

A member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, the Phanatic is the premier mascot in all of sports, rivaled only, perhaps, by the Famous Chicken. The Phanatic roams the entire park, taunting opposing players and coaches, umpires, and even fans. When not spilling popcorn, spit-shining bald heads, dancing with third-base coaches, and riding around on his ATV, the Phanatic shoots hot dogs into the crowd with his hot dog launcher.

The Phanatic debuted in 1978. Originally David Reymond wore the costume but Tom Burgoyne took the mantle in 1993. The costume, which was designed by the same company that designs the Sesame Street characters, weighs thirty-five pounds.

The large and in charge rapping Monte G is a local sports cult figure who is easily recognized by his oversized white T-shirt that’s self-painted with phrases supporting the home team … and by his red-and-white curly wig. And by the news crews that often seek him to get his prediction before big games. And by the fact that he gets invited to dance atop the Phillies dugout with the Phanatic, where he matches the mascot move for move. Monte G first achieved fame with his YouTube Phillies’ rap, which you can search.

Pete Adelis was known as “the Iron Lung of Shibe Park” due to the extraordinary volume at which he heckled the Phillies opponents back in the 1940s. He even published a list entitled “The Rules of Scientific Heckling” in an issue of the

Sporting News

in 1948. These included:

- No profanity

. - Nothing purely personal

. - Keep pouring it on

. - Know your players

. - Don’t be shouted down

. - Take it as well as give it

. - Give the old-timer a chance—he was a rookie once

.

Cyber Super-Fans

These bloggers and message board operators dedicate their lives to the hometown Phillies, even if they live elsewhere. The advantage for you? You can be on the inside track for Phillies info no matter where you live.

- Phillies Phans

- Phillies Nation

- The Good Phight

- Fightin’ Phillies

- Phillies Blog

We Jammed the Can, Philly-Style

We rolled into Philadelphia after midnight, road-weary and ready for some much-needed rest. No such luck. We arrived at Kevin’s friend Dave Hayden’s house to find the party just getting started. Sort of.

More accurately, we found the remnants of a little girl’s outdoor suburban birthday party, and the dads that were keeping the party rolling into the wee hours. After grabbing a brew and feasting on the leftover crabs in the fridge, we settled in to watch Dave and his neighbors play a tailgate game we’d never seen before called Can Jam.

It was so basic it was genius. All you need are four players (two teams of two), a single Frisbee, and two plastic garbage “cans” to jam the Frisbee into.

The rules seemed a bit fluid at this late point in the evening, but we’ll try to re-create them for you as best as possible.

- It’s a horseshoes-style game played with a Frisbee and garbage cans with the tops off and a slot cut out of the front

. - The major difference between horseshoes and Can Jam is that the teammate of the player that throws the Frisbee gets to slap the disc (or jam it) into the can

.a. Simply hitting the can with a slapped Frisbee is worth one point

b. Slapping it into the can is worth two points

c. Tossing the Frisbee into the can without touching it is worth three points

d. Tossing the Frisbee into the slot on the front of the can is an instant game winner

- Game goes to 21—must win by two

. - No matter what happens, the team that is behind gets a final set of throws

.

Pretty simple, right? Well, we wish we thought of it. We played round after round of Can Jam. We hooted and hollered into the late suburban Philly night.

“Dave,” Kevin said, “Are we keeping any of your neighbors awake?”

“Nah,” said Dave, “They’re all here.”

When in Rome.

There was drunkenness, some of the worst Frisbee throwing we’ve ever seen in our lives, friends that kicked the can in fits of rage at the futility of their skills, and a phone call from Dave’s wife, Kate, letting him know that we were indeed keeping her awake, even though their bedroom was on the other side of the house … and all the doors and windows were shut tight.

Well, wanting to get to the ballpark early the next morning for a Sunday afternoon noon game, we hung up our Frisbees at 3:00 a.m. and called it a night.

The next day we loaded up the Can Jam components, all set to share our newfound love of the sport with the tailgating Philly public. The problem was, tailgating is not allowed in the parking lots of the South Philly Sports Complex!

It was frustrating, to be certain, but we knew we would have plenty of opportunities to share Can Jam with an appreciative tailgating populace, if not on this road trip, then on the next.

WASHINGTON NATIONALS,

WASHINGTON NATIONALS,NATIONALS BALLPARK

The National Pastime Returns to our Nation’s Capital

W

ASHINGTON

, D.C.

40 MILES TO BALTIMORE

124 MILES TO PHILADELPHIA

225 MILES TO NEW YORK CITY

244 MILES TO PITTSBURGH

W

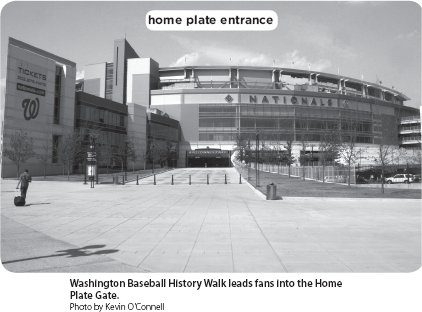

ashington, D.C. has a long baseball tradition, but in recent years had been without a team. When the city got back in the game in 2005, the Nationals played at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium, one of the last remaining multi-use cookie cutter stadiums, and a facility that did next to nothing to enhance the game-day experience for fans. With the 2008 opening of Nationals Ballpark in the South Capitol neighborhood known as the Navy Yard, though, the citizens of D.C. now have a ballpark they hope to call home for quite some time.

Nationals Park was designed by Populous, and its construction was funded by the city of D.C., which shelled out $611 million to lure baseball back within the city limits. To us, that amount seems like a lot to pay. Architecturally, Nationals Park’s interior is its strength, while its exterior projects the image more of a generic sports stadium than of a baseball park. Perhaps the retro look has become passé, or the designers who had a hand in cranking out fifteen ballparks in the eighteen years after Camden Yards became the “game changer” decided to turn away from the past, and toward the future. This tendency can also be observed in more recent Populous-designed parks like Target Field in Minneapolis and Marlins Ballpark in Miami. Nationals Ballpark typifies this movement. Its white-and-gray stone façade are reminiscent of the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and many of the other historical structures of our nation’s capital. While this is nicely done, it doesn’t cry out to the soul of the wandering baseball traveler the way the brick façade of Fenway Park does.

But inside, Nationals Park is a fan’s delight. To the experienced baseball traveler, upon first glimpse, the park is sure to conjure images of ballparks past. The field and surrounding stands provide almost everything a baseball fan could want. The beautiful green grass, brown dirt, and white chalk of the field are complemented beautifully by blue and red seats all angled toward the action, several distinctive design features, a robust lineup of unique foods, and a small but growing group of fans. Together, these effects make a game in Washington a cornucopia of wondrous sights, smells, flavors, and sounds. In short, this is baseball at its finest.

To say D.C. hardball fans waited a long time for this yard is akin to saying the “goddesses” will be waiting a long time to marry Charlie Sheen. For thirty-three seasons, our National Pastime was not played at the Major League level in Washington, D.C. For true fans of the game, those were three long decades. But at long last, D.C. rooters are no longer forced to

drive to Baltimore to see a game. This happy development has transpired much to the chagrin of Orioles’ owner Peter Angelos, however. For years the former-trial-lawyer-turned-owner fought to block D.C. from getting a team, claiming the city was part of the Orioles’ territory. Whatever “territory” means to a migratory bird!

Not only were Beltway fans left without a team, but many hadn’t even been alive long enough to remember when there had been a home team and/or quality baseball park in town. Prior to the Nationals’ debut at RFK in 2005, the Senators team that eventually left the capital city to become the Texas Rangers in 1972 had been the last home team to play in D.C. The team had played its inaugural season at Griffith Stadium in 1961 before moving to the newly minted RFK in 1962.

The history of baseball in D.C., much like the histories of the many fine people who spend their lives in service to our country, working in our nation’s capital, can be summed up in a single word: transient. It’s a town full of people who hold dear the impressive history, stories, and culture so vital to our nation, but the transient nature of the population partly explains why our National Pastime hasn’t always fared so well there. Most of the congressional staffers and K Street lobbyists arrive in D.C. with their baseball loyalties already firmly rooted in faraway cities. They still follow the game, but they’re passionate for their own home team, wherever it may be, and don’t quite have room in their hearts for the team that plays just down the street from where they work. And thus, baseball has a history of foundering in D.C.

Well, that isn’t entirely true. For limited stretches of time, the game has flourished in this town too. And when it has, the home team has enjoyed a level of fan devotion that has bordered on the criminally insane, which we mean as a compliment, of course. From 1901 to 1960, an American League incarnation of the Washington Senators called D.C. its home, before relocating to Minnesota to become the Twins. From 1961 through 1971, the second version of the Senators played in D.C., before departing for Texas to become the Rangers. So, in essence, fully 3/30ths of today’s MLB baseball teams owe their origins to D.C.

Kevin:

Oh wait. I know this one … that’s one-tenth!

Josh:

Or 10 percent.

Kevin:

Is it me, or are our math skills improving?

Prior to 1900, a variety of other teams called D.C. home too, but none stayed. There were the Olympics, the Blue Legs, another incarnation of the Senators, and four different versions of the Nationals that played in the Union Association, the National Association, the American Association, and the National League. That first Senior Circuit Nats team stayed in town from 1886 through 1889. The Homestead Grays were another team that played in D.C. for a while. The famous Negro Leagues franchise played many of its home games at Griffith Stadium, even though it was always a Pittsburgh-based club.

After both the junior and senior Senators departed in the 1960s and 1970s, the fortunes of baseball fans in D.C. finally turned sunny again in 2005. For the first time in the capital city’s history, a team arrived from another town instead of departing for one, when the National League Montreal Expos pulled up stakes in the Great White North and headed south. The final three name possibilities for the new team came down to Grays, Senators, and Nationals.

Surely, the fact that a National League team came had a hand in the pick ultimately being the “Nationals.” The track record with the “Senators” moniker wasn’t too good anyway. As for “Grays,” we both think that would have been kind of blah.

While some contemporary fans may refer to the Nationals as the game’s newest team, this isn’t entirely accurate. The franchise carried with it a long—if less than proud—history from its days in Montreal. And we believe those years shouldn’t be forgotten. During our first baseball adventure, the Nationals’ franchise belonged to another nation. And our visit to the Expos’ decrepit old dome took place during what we suspected were MLB’s dying days in Montreal. An underhanded deal made behind closed doors had allowed the other twenty-nine Major League teams and their owners to assume control of the Expos in 2002 which, in essence, spelled their doom. Those other twenty-nine owners had ordered Expos general manager Omar Minaya to slash the team’s payroll prior to the 2003 season, which forced him to deal staff ace Bartolo Colon to the White Sox. Though the final destination of the team had yet to be determined, it was clear to nearly all observers that the team’s future would not be in Montreal. This was, needless to say, a sad development for the Expos’ fans, who were remarkably loyal during the team’s stay in Montreal until it became apparent that the team had no future there.

Believe it or not, upon entering the National League in 1969, Montreal outdrew the three other expansion teams who joined the Major Leagues that year—the Los Angeles Angels, San Diego Padres, and Seattle Pilots. The Expos were the only franchise among the trio of newbies to eclipse the one-million mark in attendance at their Jarry Park. Montreal fans brought a raucous hockey-crowd mentality to games and in fact the Expos attracted more than a million fans in each of their first six seasons at a time when the average

National League team was drawing 1.3 million. This, at a thirty-five-thousand-seat temporary stadium that was widely considered the worst ballpark in the bigs. Jarry had its clubhouses down the left-field line, which required players to walk behind the stands to get to the dugouts. And the ballpark was oriented so that the setting sun blinded first basemen as they awaited throws from the left side of the diamond. What’s more, none of the seats in the one-level stadium were covered by a roof. But Jarry had at least one thing going for it. On sunny days, fans could abandon the game and make use of a public swimming pool located just outside the gates beyond the right-field fence. But most fans stayed until the last out before taking a dip.

Kevin:

Take that Arizona! The folks in Montreal had a pool before you!

Josh:

But did they have a retractable roof?

Kevin:

Well, actually, they did … sort of.

While the Expos drew respectable crowds to Jarry Park, Montreal was fast at work on Olympic Stadium, which would not only host the 1976 Summer Games, but then provide the Expos with a revolutionary new ballpark. Eventually, the intention was to make “the Big O” a retractable-roof dome. Talk about being ahead of its time, eh? The facility was also to be the Major League’s first fully bilingual park, providing all public address announcements in both English and French.

The City of Montreal finished constructing Olympic Stadium just in time for the 1976 Olympics. The following year, the dome became the Expos’ new home. Unlike Turner Field in Atlanta, however, which was remodeled to accommodate baseball after hosting the 1996 Summer Games, Montreal did little more than throw down artificial turf and paint baselines on the plastic in preparation for the Expos’ arrival. Nonetheless, the team was soon drawing more than two million fans a season.

Outside Olympic Stadium a 623-foot-high inclined tower hung above the center of the playing field like a loon’s neck. A sixty-five-ton Kevlar roof, suspended by cables, hung from the tower. The roof was originally meant to open and close in forty-five minutes. But it never worked properly, so the Big O eventually became a fixed dome when management gave up on the retractable roof idea in 1989. In 1998, however, the Expos removed the umbrella at midseason, making Olympic an open-air facility. But the big top was eventually put back in place.

The Expos were poised to go deep into the playoffs in 1994. They had the best record in baseball (74-40) and had drawn 1.3 million fans to fifty-five home dates when the season ended on August 12 because of the players’ strike. In their final home game, played on August 4, against the Cardinals, the Expos drew 39,044 fans. Not too shabby, eh?

As Tom Glavine led the Players Association into battle, his Atlanta Braves sat six full games behind the Expos in the NL East standings. But the season never resumed, and the next year the Expos sank to last place in their division, having lost key players like Ken Hill, Marquis Grissom, Larry Walker, and John Wetteland to the clutches of baseball’s new economic realities. After the longest work-stoppage in the game’s history, fans grudgingly returned to the ballparks in most big league cities, but not in Montreal. With gate revenue on the decline and the Canadian dollar plummeting faster than a Chien-Ming Wang sinkerball, Montreal was unable to retain its emerging stars in the years ahead. In addition to the players mentioned above, other key losses included Pedro Martinez, Cliff Floyd, Moises Alou, Delino DeShields, David Segui, Rondell White, and Jeff Fassero, all of whom departed via free agency or lopsided trades designed to reduce payroll. Feeling betrayed by the game, the Montreal fans stopped turning out at the ballpark. By 1999 home attendance had sagged to less than ten thousand per game.

The final death knell for the Expos came in February 2002 when Jeffrey Loria sold his controlling interest in the team to Major League Baseball’s other twenty-nine owners for $120 million. In turn, Loria bought the Florida Marlins from John W. Henry, who turned around and bought the Boston Red Sox. Loria brought with him to Florida his front office staff from Montreal, leaving the Expos without personnel and even so much as scouting reports on the other NL teams. Under the ownership of MLB, the Expos finally replaced Olympic Stadium’s aged green carpet. Tellingly, however, the new artificial turf was leased, not bought, by the league, with a club option for a second year, signifying quite clearly that MLB had no intention of laying down roots—even artificial ones—in Montreal.