Ultramarathon Man (27 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

“I'm so happy we could meet here, this is wonderful.”

“Team Dean,” a reporter called out, “would you mind turning around for the cameras?”

The barrage of flashing cameras scared Libby, and she twisted and squirmed in my arms with amazing strength.

“She's going to be a runner,” I announced, trying to keep her from wiggling free.

Someone put a medal around my neck, and they snapped some more pictures of us together. Then the questions began:

Q: “Did you sleep?”

A: “Just once, but it wasn't very restful.” (I didn't mention that I was running at the time.)

Q: “What did you eat?”

A: “Anything I could get my hands on.”

Q: “Where did you go to the bathroom?”

A: “In the bushes. I looked for dry ones that needed watering.”

Q: “What kept you going?”

A: “This little future runner right here.”

Â

Â

I held up Libby, who was smiling but still kicking away. The crowded laughed.

Like me, Libby had a wonderful family to support her on her journey. They had all come to Santa Cruzâaunts, uncles, grandparentsâand the bunch of us spent the rest of the afternoon celebrating together and cheering like crazy as the other teams came running in. We promised to meet up here again next yearâa pledge we devoutly hoped Libby would be able to keep. But the sad fact was that the odds were stacked against her.

As the sun began to set and the crowds drifted away, Alexandria took my hand and said, “Daddy, can we go now?”

“Of course we can, dear.” I was sweaty, filthy, and light-years beyond exhaustion, dreaming of a bath and bed.

Then she enthusiastically proclaimed: “Look at all the tickets we've got!” She was clutching a full deck of amusement-park tickets in her hands.

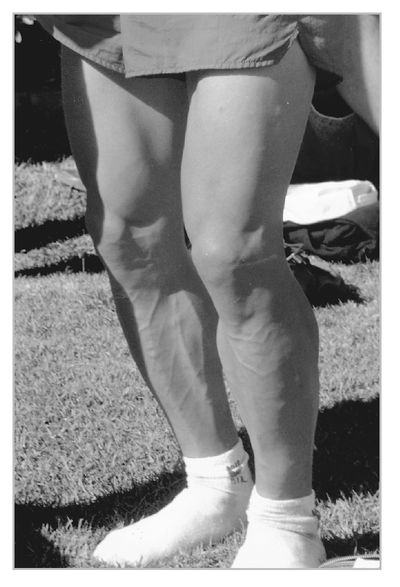

My legs after running 200 miles

“Where did you get all those?”

“Dr. Shapiro gave them to us.”

“That Dr. Shapiro,”

I mumbled under my breath,

“what a guy.”

I mumbled under my breath,

“what a guy.”

“What, Dad?”

“I said . . . âThat . . .

rollercoaster

, what a

ride

!'” I turned to Julie. “Hey, Mom, coming with us?”

rollercoaster

, what a

ride

!'” I turned to Julie. “Hey, Mom, coming with us?”

“You kidding?” she replied. “I'm going to sleep in the campervan.”

“Where are the folks?”

“Asleep in the campervan.”

“Gaylord?”

“Asleep in the campervan.”

“Come on, kids,” I perked. “Last one to the rollercoaster rides in back!”

The three of us went sprinting toward the Boardwalk, fistful of tickets in hand. No time to waste resting; one endurance event had just ended, and another had just begun. I loved it. What better way to spend our Sunday evening; what more fitting conclusion to a glorious weekend. Brutalized, hobbling, and running from one ride to the next on sheer adrenaline, I was the happiest man on earth.

Â

Â

Â

By 7:45

the next morning, I was back at my desk, preparing for our weekly eight o'clock meeting. There was a lightness in my step this morning, even though it had taken me three attempts to drag my battered body out of my car. Luckily our offices were on the ground floor; stairs would have presented an insurmountable obstacle. It would take months to fully recover from the run, but it was a good hurt.

the next morning, I was back at my desk, preparing for our weekly eight o'clock meeting. There was a lightness in my step this morning, even though it had taken me three attempts to drag my battered body out of my car. Luckily our offices were on the ground floor; stairs would have presented an insurmountable obstacle. It would take months to fully recover from the run, but it was a good hurt.

I was now working in the marketing department of a software company. Ron from the research department approached my desk. “Can you help me move these tables around? I've got a client coming in at nine.”

“Sure.” I pried myself up entirely by arm strength.

“You all right?” he asked.

“Yeah, just a little sore.”

“Weekend-warrior syndrome?”

“You could say that.”

Back to work the next morning

“Softball? I threw my back out a couple weeks ago playing a game.”

“Actually, I did it running.”

“That'll do it. My doctor told me not to run. It's tough on the body.”

“I'll attest to that. But I can't seem to give it up.”

“Whatever flips your switch,” he said with a shrug.

We moved the tables and I hobbled back to my desk. My fifteen minutes of fame were yesterday's memory. Today I was back to

Dean down the hall in the office second from the left.

There was glory in running, but there would never be fame and fortune. I wouldn't be giving up my day job anytime soon.

Dean down the hall in the office second from the left.

There was glory in running, but there would never be fame and fortune. I wouldn't be giving up my day job anytime soon.

Happiness, though, cannot be measured in monetary terms. My job paid the bills; my running satisfied a deeper passion. Limping into the weekly meeting, dehydrated, stiff, and on the verge of collapse, my heart was fulfilled. I couldn't ask for anything more.

Chapter 18

The Gift

of Life

of Life

Runs end. Running doesn't.

âUnknown runner

2000-2004A week after The Relay,

a miracle occurred. Libby received her organ transplant. She had run the race of her life, and she had won.

a miracle occurred. Libby received her organ transplant. She had run the race of her life, and she had won.

Playing a small role in helping to save Libby was one of the most enriching accomplishments of my life. If I could use my running to benefit others, it gave new meaning to the pursuit. I wanted to do more.

I ran The Relay solo again the subsequent year, this time for a little boy named David Mehran who, like Libby, needed a liver transplant. Despite improbable odds, young David also received the gift of life a week after The Relay. I wanted to run more.

The next challenge was even grander. Valeria Casterjon-Sanchez was just six weeks old and suffered from a failing heart. The probability of her surviving was very poor. My only recourse was to try harder, to push even farther. So after running 200 continuous miles to complete The Relay, I turned around and ran an additional marathon, making the entire journey 226.2 miles. My toughest challenge to date.

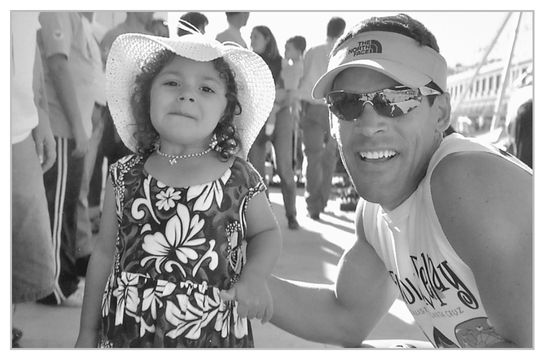

Libby Wood, post-transplant

A week passed after The Relay. No change. Two weeks passed, still nothing. Three weeks, only despair. The magic that had astounded us in previous years seemed gone. Valeria was slipping away.

Then, on the fourth week after The Relay, it happened. Valeria received a new heart.

That string of miraculous outcomes left me with an eerie sense of providence, as if it were somehow my calling to be involved. I'm not getting saccharine here, and believe me, I'd probably be running like a wildman no matter what, but thinking about my sister, and being able to help others, has given me a greater sense of purpose; it has allowed me to think of something, someone other than myself, in what can often be a solitary and selfish sport.

Yet there are no free rides. Just like the loneliness and desolation long-distance running can inflict upon a family, organ donation presents a similar conundrum. Dr. Shapiro, who has become a dear friend, once said to me, “The gift of life is always bittersweet,” meaning that with organ donation, for one life to be saved, another must slip away.

The weight of this paradox troubled me for some timeâuntil I met Greg Osterman. Greg exuded energy from every pore, as if each second of his life was a precious gift meant to be savored and lived to its fullest.

We ran across the Golden Gate Bridge together, and I learned his story. Greg held the world record for the most marathons completed,

post-heart transplant.

He had finished a remarkable eight marathons after receiving a new heart, and he was gunning for more. Yet he hadn't always been a runnerâquite the opposite, actually.

post-heart transplant.

He had finished a remarkable eight marathons after receiving a new heart, and he was gunning for more. Yet he hadn't always been a runnerâquite the opposite, actually.

A commercial plumber, Greg led a sedentary life until age thirty-seven, when he was diagnosed with cardiomyopathy and eventually given only twenty-four hours to live. He received a new heart from an eighteen-year-old girl who was the victim of an automobile accident. Pary had died in an automobile accident on her eighteenth birthday.

Greg is forever grateful to his donor and her family, and he has vowed to run eighteen marathons, one for each year of the life of the girl who saved his.

The grieving family and loved ones of organ donors are often sustained by knowing that their loss has saved the life of another. Which ultimately made me wonder: Could Pary's tragic death have saved someone else's life? Organ donation wasn't as widely practiced at the time of her death as it is now. But what if it had been? Could she have passed along the gift of life to someone else?

And then it occurred to me: she did. Even if her body was not shared, her spirit was. She had passed along the gift of lifeâto me.

Â

Â

Â

So now's

the time to get back to the existential pizza-delivery guy who'd asked at the beginning: “So, dude, do you mind me asking

why

you're doing this?” I've had some miles to ponder that one, and now I think I can answer him.

the time to get back to the existential pizza-delivery guy who'd asked at the beginning: “So, dude, do you mind me asking

why

you're doing this?” I've had some miles to ponder that one, and now I think I can answer him.

I'll start with the obvious: running has as much power over me as I have over running. Sometimes, when I haven't run for several days, the balance is shifted and running gains the upper hand, and the impulse to run becomes unwieldy. But most of the time, it's a good partnership.

Often, people can't understand how running can have such power. They say it's little more than a slightly ambitious version of walking. True, running is a simple, primitive act. Yet in its subtleties lies tremendous power. For in running, the muscles work a little harder, the blood flows a little faster, the heart beats a little stronger. Life becomes a little more vibrant, a little more intense. I like that.

I also like the solitude. Long-distance running is a loner's sport, and I've accepted the fact that I enjoy being alone a lot of the time. It keeps me fresh, keeps meâoddly enoughâfrom feeling isolated. I guess a lot of people find it in church, but I turn to the open road for renewal. Running great distances is my way of finding peace.

The solitude experienced while running helps me enjoy people more when I am around them. The simple, primitive act of running has nurtured me. I've become more tolerant, more patient, and more giving than I ever thought I could be. Suddenly the commonplace is intriguing, and I've learned to dig the little things in life, like being squirted in the ear with a water bottle by a five-year-old child. This is what running has taught me, making meâI hopeâa better man.

So Mr. Pizza Delivery Dude, here you have the answer: I run to see how far I can go. I run because it's my way of giving back to the world by doing the one thing it is I do best.

I run because I've never been much of a car guy. I run because if I didn't, I'd be sluggish and glum and spend too much time on the couch. I run to breathe the fresh air. I run to explore. I run to escape the ordinary.

I run to honor my sister and unite my family. I run because it keeps me humble. I run for the finish line and to savor the trip along the way. I run to help those who can't. I run because walking takes too long, and I'd like to get a few things done in this lifetime.

Other books

Working Girls by Katt

Ignite (Midnight Fire Series Book One) by Kaitlyn Davis

Together With You by Victoria Bylin

More Than I Can Bear by E.N. Joy

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd

Sarah My Beloved (Little Hickman Creek Series #2) by Sharlene Maclaren

Deceived (Private Justice Book #3): A Novel by Irene Hannon

Eichmann en Jerusalén. Un estudio acerca de la banalidad del mal by Hannah Arendt

Kara by Scott J. Kramer

Temptation by Douglas Kennedy