UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (33 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

After reading it I thought perhaps, for some mysterious reason, you were lying (nor is it difficult to conclude from your life, as you have so frankly related it, that you do sometimes lie). If there is anyone who should know for sure that you didn't kill me, it would be I myself. I wanted to investigate. I removed my clerical garb and, almost naked, went down to the cellar and opened the trap door. At the entrance to that foulsmelling passageway that you so well describe, I was taken aback by the stench. I asked myself what it was I wanted to find out: whether there were still a few bones from the body you say you left down there over twenty-five years ago. And did I have to go down into that filth to discover those bones weren't mine? If you'll allow me, I already know. Therefore I accept what you say — you did kill an Abbé Dalla Piccola.

So who am I? Not the Dalla Piccola you killed (who in any event didn't look like me). But how can there be two Abbé Dalla Piccolas?

The truth is perhaps I'm mad. I dare not leave the house. Yet I have to go out to buy food, since my cassock prevents me from visiting taverns. I do not have a fine kitchen like you — though, to be honest, I am no less of a glutton.

I am gripped by an irresistible urge to kill myself, but I know it's the devil tempting me.

And then, why kill myself if you have already done it for me? It would be a waste of time.

7th April

Dear Abbé, enough of this.

I have no recollection of what I did yesterday and found your note this morning. Stop tormenting me. You don't remember either? So do as I do — contemplate your navel and then start writing. Allow your hand to think for you. Why is it I who has to recall everything, and you who remember only the few things I wanted to forget?

At this moment I am beset by other memories. I had just killed Dalla Piccola when I received a note from Lagrange. This time he wanted to meet me at place de Fürstenberg, at midnight, when the place is fairly ghostly. I had, as God-fearing people would say, a guilty conscience, as I had killed a man, and feared (irrationally) that Lagrange already knew. But he obviously had something else to talk about.

"Captain Simonini," he said, "we need you to keep an eye on a curious character, a priest . . . how can I put it . . . a satanist."

"Where do I find him, in hell?"

"I'm not joking. He's a certain Abbé Boullan, who years ago came to know a certain Adèle Chevalier, a lay sister in the convent of Saint- Thomas-de-Villeneuve at Soissons. Strange rumors began to circulate about her. It was said she had been cured of blindness and had made prophecies. The convent began to fill up with followers, her superiors became worried, the bishop moved her away from Soissons, and all of a sudden our Adèle chooses Boullan as her spiritual guide, and no doubt they're well matched. So they decide to establish a society for the reparation of souls — in other words, dedicating themselves to Our Lord not only through prayer but through various forms of physical atonement, to make good for the wrongs done by sinners against him."

"No harm in that, I'd have thought."

"Except that they start preaching that you have to commit sin in order to free yourself from it, that humanity was debased by the double adultery of Adam with Lilith, and Eve with Samael (don't ask me who these people are — in my church I was taught only about Adam and Eve), and that you have to do certain things that are not yet entirely clear. But the abbé, the young lady and many of their followers were apparently involving themselves in gatherings that were, shall we say, indecorous, where each was abusing the other. It was also rumored that the good abbé had discreetly disposed of the fruit of his illegitimate liaisons with Adèle. All things, you might say, that are of interest to the prefect of police rather than us, except that some time ago a number of respectable women joined the throng, the wives of high officials, even of a government minister, and Boullan managed to wheedle large sums of money out of these pious ladies. At this point the whole business became a state matter, and we had to take it over ourselves. The two of them were arrested and sentenced to three years' imprisonment for fraud and indecent behavior, and were released at the end of '64. Then we lost track of the abbé and thought he might have turned over a new leaf. But he recently reappeared in Paris, having finally been absolved by the Holy Inquisition after numerous acts of penitence, and is back proclaiming his beliefs that people can redress the sins of others through the cultivation of their own, and if everybody starts thinking like that, the whole business would no longer be religious, but political. You understand? The Church itself has started to worry once more, and the archbishop of Paris has recently banned Boullan from ecclesiastical duties — and about time, I'd say. Boullan's only response has been to make contact with another holy man of heretical leanings, a certain Vintras. Here in this small dossier you'll find all there is to know about him, or at least all that we know. Keep an eye on him and find out what he's up to."

"As I'm not a pious lady in search of a confessor to take advantage of her, how do I approach him?"

"No idea. Dress up as a priest, perhaps. I gather you've managed to pass yourself off as one of Garibaldi's generals, or something like that."

That's what has just come back to mind. But, my dear Abbé, it has nothing to do with you.

16

BOULLAN

8th April

Captain Simonini, during the night, after reading your indignant note, I decided to follow your example and have settled down to write almost automatically (though without staring at my navel), allowing my hand to record what my mind had forgotten. That Doctor Froïde of yours wasn't such a fool.

Boullan . . . I can see myself walking with him in front of a church on the edge of Paris. Or was it at Sèvres? I remember him saying to me: "Reparation for the sins committed against Our Lord means taking responsibility for them. Sin can be a mystical burden, and the heavier the better, so we can relieve that load of iniquities the devil exacts from humanity, and we can unburden our weaker brothers who are incapable of exorcising the evil forces to which they are enslaved. Have you ever seen papier tuemouches, which was recently invented in Germany? Confectioners use it. They cover a piece of tape with treacle and hang it in the window above their cakes. Flies are attracted to the treacle, are caught in the sticky substance on the tape and die of asphyxiation, or are drowned when the tape, crawling with insects, is thrown into the gutter. Well, the faithful reparator must be like this flypaper: he must attract every ignominy upon himself and then become the purifying crucible."

I see him in a church where, before the altar, he has to "purify" a dev otee, a woman possessed, who squirms on the ground uttering disgusting blasphemies and naming demons: Abigor, Abracas, Adramelech, Haborym, Melchom, Stolas, Zaebos . . .

Boullan is wearing purple vestments with a red surplice. He stands above her and pronounces what seems to be the formula for an exorcism, but (if I heard correctly) saying the opposite:

"Crux sacra non sit mihi lux, sed draco sit mihi dux, veni Satanas, veni!"

He bends down over the penitent and spits into her mouth three times, then lifts his vestments, urinates in a chalice and offers it to the poor woman. Then he takes a substance of evident fecal origin from a bowl (with his hands!) and, having exposed the possessed woman's chest, smears it over her breasts.

The woman thrashes about on the ground, gasping and letting out groans, which gradually subside until she falls into an almost hypnotic sleep.

Boullan goes into the sacristy, where he cursorily washes his hands. Then he goes out with me to the forecourt, sighing as if he has performed a difficult duty.

"Consummatum est,"

he says.

I remember telling him that I had come on behalf of someone who wished to remain anonymous and who wanted to practice a ritual where consecrated hosts were required.

Boullan smiled contemptuously. "A black mass? But if a priest is taking part, he consecrates the hosts there and then, and the whole thing would be valid even if he's been defrocked."

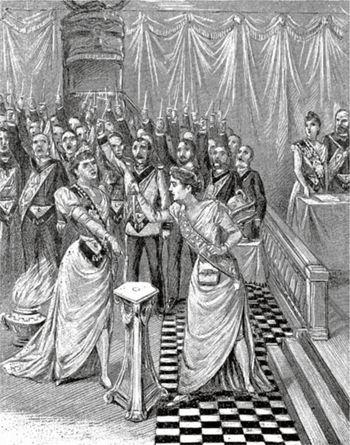

I explained: "I don't think the person I'm referring to is looking for a priest to officiate over a black mass. You may know it is the practice in certain lodges to stab the host to seal an oath."

"I see. I've heard there's a bric-a-brac dealer somewhere near place Maubert who also sells hosts. You could try him."

Was it on that occasion the two of us first met?

"You may know it is the practice in certain lodges to stab the

host to seal an oath."

17

THE DAYS OF THE COMMUNE

9th April 1897

I killed Dalla Piccola in September 1869. In October I received a note from Lagrange, calling me, this time, to a

quai

on the Seine.

What tricks the mind can play. Perhaps I am forgetting facts of vital importance, but I remember the excitement I felt that evening when, on the Pont Royal, I was amazed to see a sudden bright light. I was in front of the site for the new offices of the

Journal Officiel de l'Empire Français

, which was lit by electricity at night to speed up the work. In the midst of a forest of beams and scaffolding, powerful rays shone down on a group of builders. Words cannot describe the magical effect of that great glow flaring out into the surrounding shadows.

Electric light . . . During those years, some were stupid enough to feel excited about the future. A canal had been built in Egypt to join the Mediterranean with the Red Sea, so you no longer had to go around Africa to reach Asia (thus harming many honest shipping companies); a great exhibition was opened, and judging from its architecture, it was apparent that what Haussmann had done to ruin Paris was only the beginning; the Americans were completing a railway line that would cross their continent from east to west, and since Negro slaves had just been given their freedom, they could now invade the whole nation, swamping it with half bloods, worse than the Jews. Submarine boats had appeared in the American war between North and South, where sailors no longer died from drowning but from suffocation; our parents' fine cigars were being replaced by measly cartridges that burned down in a minute, destroying every pleasure for the smoker; and our soldiers were now eating rotten meat conserved in metal cans. The Americans were said to have invented a hermetically sealed cabin that lifted people to the upper floors of a building using some kind of water piston — and there was already news that some pistons had broken one Saturday evening and people were stuck inside the box for two nights without air, not to mention water or food, and they were found dead on the Monday.

Nevertheless, everyone embraced the promise of an easier life. With one machine people could talk to each other over a distance; with another they could write mechanically, without a pen. Would there be any original documents left to counterfeit?

People gazed in wonder at the windows of perfume sellers who celebrated the miraculous invigorating qualities of wild lettuce sap for the skin, a hair restorer containing quinine, Crème Pompadour with banana water, cocoa milk, rice powder with Parma violets, all devised to make lascivious women attractive, but now available even to seamstresses ready to become kept women, since many dressmaking firms were introducing sewing machines to take over their jobs.

The only interesting invention in recent times has been a porcelain contraption that enables you to defecate while seated.

Not even I, though, had realized that this apparent excitement would mark the end of the empire. At the Exposition Universelle, Alfred Krupp had shown a fifty-ton cannon, a size never before seen, with an explosive charge of a hundred pounds per shell. The emperor was so fascinated by it that he awarded Krupp the

Légion d'honneur

, but when Krupp sent him a catalogue of weapons he was prepared to sell to any European state, the French high command, who had their own preferred arms dealers, persuaded the emperor to decline the offer. The king of Prussia, on the other hand, was evidently buying.

Napoleon was not able to reason as clearly as he used to: his kidney stones prevented him from eating and sleeping, not to mention riding a horse; he accepted the advice of the conservatives and his wife, who were convinced that the French army was the best in the world, whereas (as it later turned out) it had no more than a hundred thousand men against four hundred thousand Prussians; and Stieber had already sent reports to Berlin about the

chassepots,

which the French believed to be the last word in rifles, but had already become museum pieces. Moreover, Stieber was pleased to note, the French had failed to assemble an intelligence service equal to theirs.

But let us get to the point. I met Lagrange at the agreed place.

"Captain Simonini," he said, ignoring all formalities, "what do you know about Abbé Dalla Piccola?"