UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (35 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

While news was arriving of the French government's withdrawal to Versailles, I received a note from Goedsche telling me that the Prussians were no longer interested in what was going on in Paris and so the pigeon loft and photographic darkroom would be dismantled. But on the same day I received a visit from Lagrange, who appeared to have guessed what Goedsche had written.

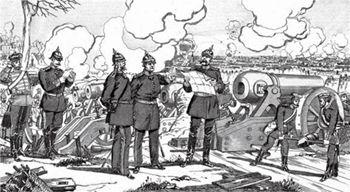

By mid-September the Prussians had reached the gates of

Paris, had occupied the forts that should have protected the

city, and were shelling it.

"My dear Simonini," he said, "you must do for us what you were doing for the Prussians, and keep us informed. I've just had those two wretches you were working with arrested. The pigeons have returned where they were trained to go, but we can make use of the darkroom materials. We had our own fast line of communication for military information between Issy fort and an attic room in the Notre Dame area. You'll send us your information there."

"You'll send 'us'—us who? You were, how do you say, a member of the imperial police. You ought to have gone with your emperor. Now it seems you're speaking as an emissary of the Thiers government."

"Captain Simonini, I am one of those who remain even when governments go. I'm following my government to Versailles — if I stay here, I'll end up like Lecomte and Thomas. These lunatics are quick to shoot, but we can give just as good as we get. When we need to know something specific you'll receive more detailed orders."

Something specific . . . Easier said than done, given that different things were going on in different parts of the city — platoons of the National Guard were parading with the red flag and with flowers in their rifle barrels in the same districts where respectable families had locked themselves inside their houses waiting for the return of the lawful government. Among those elected to the Commune, it was impossible to understand, either from the newspapers or from the gossip in the marketplace, who was on which side, since they included laborers, doctors, journalists, moderate republicans, angry socialists and diehard Jacobins who dreamt of returning not to the Commune of 1789 but to the Terror of '93. But the atmosphere in the streets was of great gaiety. Had it not been for the men in uniform, you might have imagined a large popular celebration. The soldiers were playing what, in Turin, we used to call

sussi

and here is called au

bouchon

, while officers strutted about in front of the girls.

This morning I remembered I had among my old belongings a large box full of clippings from that period, which come in handy for reconstructing what my memory alone cannot do. They were from newspapers of all leanings:

Le Rappel, Le Réveil du Peuple, La Marseillaise, Le Bonnet Rouge, Paris Libre, Le Moniteur du Peuple

and others. I don't know who read them — perhaps only those who wrote them. I had bought them to see whether they had any facts or opinions that might have been of interest to Lagrange.

I could see how confused the situation was when I met Maurice Joly one day among a confused crowd in an equally confused demonstration. He barely recognized me because of my beard and then, remembering I was a Carbonaro or something similar, assumed I was a supporter of the Commune. For him I had been a kind and generous companion in a difficult time. He took me by the arm, led me to his house (a very modest apartment on quai Voltaire) and confided in me over a glass of green Chartreuse.

"Simonini," Joly said, "after Sedan I took part in the first republican revolts. I marched to support the continuation of war, but I realized these fanatics wanted too much. During the Revolution, the Commune saved France from invasion, but such miracles of history don't happen twice. Revolution isn't proclaimed by decree, it is born from the womb of the people. There's been a moral canker in this country for twenty years; it cannot be cured in two days. France is capable only of emasculating its finest offspring. I suffered two years' imprisonment for opposing Bonaparte, and when I left prison I was unable to find a publisher who would print my new books. You'll say there was still the empire. But when the empire fell this republican government indicted me for taking part in a peaceful invasion of the Hôtel de Ville at the end of October. All right, I was acquitted, as they couldn't prove I used violence, but this is the reward for those who have fought against the empire and against that vile armistice. Now it seems the whole of Paris is basking in this Communard utopia, but you have no idea how many are trying to leave the city to avoid military service. It is said they are about to introduce conscription for all men between eighteen and forty, but look how many young men are wandering brazenly in the streets and in the districts where the National Guard won't dare to enter. Not many people want to get killed for the revolution. How sad."

Joly seemed an incurable idealist who would never be content with things as they were, though I have to say things always seemed to go wrong for him. I was concerned about his mention of conscription and decided it was time to whiten my beard and my hair. Now I looked like a dignified sixty-year-old.

In the squares and marketplaces I found many who, unlike Joly, supported the new laws, laws such as the cancellation of rent increases imposed by landlords during the siege, the return of all work tools that workers had pledged to pawnshops during the same period, the granting of pensions to the wives and children of National Guardsmen killed in action and the postponement of obligations on commercial debts. All these fine things bled the coffers of the Commune and benefited the rabble.

But that same mob (as was clear from discussions around place Maubert and in the local brasseries), while applauding the abolition of the guillotine, condemned (of course) the law that prohibited prostitution, turning onto the streets so many women in the district. So all the Paris whores emigrated to Versailles, and I have no idea where those brave National Guardsmen went to slake their lust.

Then, to alienate the bourgeoisie, there were the anticlerical laws, such as the separation of church and state and the confiscation of church property, and many rumors circulated about the arrest of priests and monks.

In mid-April an army advance guard from Versailles penetrated the northwestern districts near Neuilly, shooting every

fédéré

they captured. The Arc de Triomphe was shelled from Mont-Valérien. A few days later I witnessed the most incredible moment of the siege: the procession of Freemasons. I didn't think of the Masons as Communards, but there they were with their standards and their aprons, asking the government in Versailles to agree to a truce so the wounded could be evacuated from the districts that had been shelled. They got as far as the Arc de Triomphe, where on that occasion they met no cannon fire, as it was clear that most of their brethren were outside the city with the monarchists. In short, though there may be honor among thieves, and though the Freemasons at Versailles had worked to obtain a one-day truce, the agreement stopped there and the Freemasons in Paris were siding with the Commune.

If I remember little else about what happened on the surface during the days of the Commune, it is because I was moving around Paris under the ground. A message from Lagrange informed me of what the military high command wanted to know. It is well known that Paris is perforated by its system of drains, so often described by novelists, but beneath the network of sewers, stretching as far as its boundaries and beyond, is a maze of limestone and chalk caves and ancient catacombs. Much is known about some of these, but little about others. The army knew about the tunnels connecting the ring of fortresses outside central Paris, and when the Prussians arrived they hurriedly blocked many entrances so as to prevent the enemy from organizing an unwelcome surprise. The Prussians, however, hadn't considered entering that maze of tunnels, even when the opportunity arose, for fear of being unable to get out and losing their way in a minefield.

Very few, in fact, knew anything about the tunnels and catacombs, and most of these were criminals who used the labyrinths for smuggling goods past the city customs posts, and to escape from police roundups. My job was to question as many blackguards as possible, so as to learn my way around these passageways.

I remember, when acknowledging receipt of my orders, that I couldn't resist asking: "Doesn't the army already have detailed maps?" To which Lagrange answered: "Don't ask stupid questions. At the beginning of the war our military leaders were so sure of winning that they distributed only maps of Germany and none of France."

In times when good food and wine were scarce, it was easy to renew acquaintance with people I'd met at some

tapis-francs

and take them to a more reputable tavern where I could offer them chicken and the finest wine. They'd not only talk, but would take me on some fascinating subterranean excursions. It was just a question of having good lamps and of noting various features along the way so as to remember when to turn left or right, such as the outline of a guillotine, an old sign, a charcoal sketch or a name, perhaps drawn by someone who was never to leave that place again. The ossuaries shouldn't deter you either, since by following the right sequence of skulls, you'll arrive at some stairway leading up into the cellar of an obliging establishment from where you can emerge to see the stars again.

Some of these places were soon to be opened to visitors, but others were known at that time only to my informants.

In short, between late March and the end of May, I gained a certain expertise and sent sketches to Lagrange indicating several possible routes. Then I realized my messages were of very little use, since the government forces were now entering Paris without using the underground passageways. Versailles had five army corps by then, whose soldiers were well trained and briefed and had only one purpose, as was quickly apparent: not to take prisoners — every

fédéré

they captured had to be killed. Orders were even given, as I was to see with my own eyes, that when a group of prisoners exceeded ten, the firing squad would be replaced by a machine gun. And the regular soldiers were reinforced with

brassardiers — c

onvicts or worse — wearing tricolor armbands, who were more ruthless than the regular troops.

On Sunday the 21st of May, at two o'clock in the afternoon, eight thousand people gathered in festive spirit for a concert in the Jardin des Tuileries to aid the widows and orphans of the National Guard, no one yet realizing that the number of unfortunates to benefit was soon to increase alarmingly. At four-thirty, while the concert was still in progress (though this was only discovered later), the government forces entered Paris by the city gate at Saint-Cloud, occupied Auteuil and Passy and shot all the captured National Guardsmen. It is said that by seven o'clock that evening at least twenty thousand Versaillais were in the city, but heaven knows what the leaders of the Commune were doing. It all goes to show that organizing a revolution requires men with good military training. But such people don't get involved, and stay on the side with the power. Which is why I can see no reason (by which I mean no good reason) for staging a revolution.

On Monday morning the men from Versailles set up their cannon at the Arc de Triomphe, and someone seemed to have ordered the Communards to abandon a coordinated defense of the city and for each squad to barricade itself in its own district. If this is true, the stupidity of the

fédéré

commanders was able to shine through once again.

Barricades were erected everywhere, with the help of an apparently enthusiastic population, even in the most hostile districts of the Commune, such as those of the Opéra or Faubourg Saint-Germain, where the National Guardsmen drove the most elegant women out of their homes, spurring them to pile their finest furniture in the street. A rope was drawn across the street to mark the line of the next barricade, and everyone began depositing uprooted paving slabs or sandbags there; chairs, chests of drawers, benches and mattresses were thrown down from the windows, sometimes with the consent of the occupants, sometimes with their owners in tears, cowering in the back room of a now empty apartment.

An officer pointed to his men at work and said to me: "You too can lend a hand, citizen. We're here to die for your liberty as well!"

I pretended to join in, and made as if to pick up a stool at the far end of the street, then continued on around the corner.

The fact that Parisians have enjoyed building barricades for at least a century, and then taking them down at the first cannon shot, seems quite irrelevant: barricades are built out of a feeling of heroism, though I'd like to see how many of those who build them stay there up to the right moment. They'll follow my example, and only the stupidest ones will be left to defend them, and will be shot where they stand.

The only way to understand how events were proceeding in Paris would have been to observe them from a dirigible balloon. Some rumors suggested that the École Militaire, where the cannon of the National Guard were kept, had been occupied, others that there was fighting at place Clichy, while others claimed that the Germans were allowing the government forces to enter from the north. Montmartre was seized on the Tuesday, and forty men, three women and four children were taken to the place where the Communards had shot Lecomte and Thomas, made to kneel, and were shot one by one.