Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (39 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

That same year, soon after prohibition was lifted, Chinatown's first

two cocktail bars opened-Chinese Village and Twin Dragon; they provided Chinese American women with a new, better-paying, but controversial line of work as cocktail waitresses and nightclub entertainers.

Gladys Ng Gin was among the first to try out for these jobs. She was

making $75 a month running an elevator when a friend encouraged her

to become a waitress at the Chinese Village. As she recalled, "I didn't

know the difference between gin to rum, scotch or bourbon, but it was

good money. Ten dollars a week but great tips." Being illiterate in both

Chinese and English, she found it difficult to take orders. "I had to memorize over one hundred kinds of alcohol because I couldn't write," she

said. "You ordered and I told the bartender. Then the bartender made

the drink and I served it. But you have to remember what each customer

is drinking. And sometimes you go for another order and then come

back for the first drink."90 After two years at the Chinese Village, Gladys

followed the owner, Charlie Low, to Forbidden City, one of Chinatown's

first nightclubs. Although her mother did not object to her working in

a bar, many other people in the conservative community considered such

work immoral. As it turned out, most Chinatown women were so inhibited by their social upbringing that the nightclubs had to recruit the

large part of their talent from outside.

When he first opened Forbidden City on the outskirts of Chinatown, Charlie Low recalled, he was determined to present a modern version

of the Chinese American woman, "not the old fashioned way, all bundled up with four or five pairs of trousers," he said. "We can't be backwards all the time; we've got to show the world that we're on an equal

basis. Why, Chinese have limbs just as pretty as anyone else! "91 Purported

noble intentions aside, Charlie Low, the son of Chew Fong Low, was

known to be a shrewd businessman. Capitalizing on the end of prohibition and the beginning of the nightclub era, he invested in Forbidden

City, an oriental nightclub with an American beat. What gave Forbidden City instant fame was Charlie Low's publicity skills and his ability

to showcase Chinese Americans in cabaret-style entertainment-doing

Cole Porter and Sophie Tucker, dancing tap, ballroom, and soft-shoe,

parodying Western musicals in cowboy outfits, and kicking it up in chorus lines. Besides challenging Hollywood's misconceptions of Chinese

American talent, the novelty acts broke popular stereotypes of Chinese

Americans as necessarily exotic and foreign. Most important, Forbidden

City provided Chinese American women employment and a rare opportunity to show off their talents. "It was a beginning," said Mary

Mammon, a member of the original chorus line. "There was just no way

you could go to Hollywood [which] had a low regard for Chinese American talents. We [supposedly] had bad legs, spoke pidgin English, and

had no rhythm."92 Bertha Hing, who needed a job to support herself

through college, was one of the few local Chinatown women to join the

chorus line. "Chinatown mothers wouldn't let their daughters do anything like that. But what they didn't realize was that we all just loved to

dance. And we didn't particularly care for drinking or smoking or anything like that. It was just another way of earning a living," she said.93

From the beginning, the Chinese community felt that no respectable

parents would want their daughter to be seen in such an establishment.

As dancer Jadin Wong recalled, "Chinese people in San Francisco were

ready to spit in our faces because we were nightclub performers. They

wouldn't talk with us because they thought we were whores. We used

to get mail at Forbidden City-`Why don't you get a decent job and

stop disgracing the Chinese? You should be ashamed of yourself, walking around and showing your legs! "194 After Charlie Low added nude

acts to boost business, however, his sexploitation tactics became clear,

and the nightclub's reputation plummeted to a new low. Although many

of the female performers would have preferred not to bare their bodies,

most went along with it to keep their jobs.95 Years later, when asked in

an oral history interview if she had ever felt exploited while working at

the Forbidden City, Bertha Hing replied:

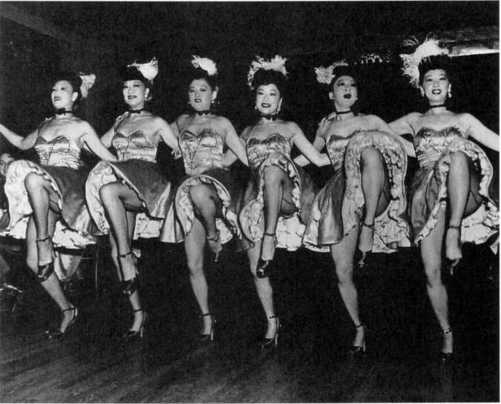

Chorus line of the Gay Ninety Revue, Forbidden City, r94z. From left to

right: Lily Pon, Ginger Lee, Connie Parks, Diane Shinn, Dottie Sun, and Mei

Tai Sing. (John Grau collection)

I tell you, those of us who started in together really loved to dance and

we liked what we were doing. I never felt like I was exploited, because I

felt that I had a choice of whether I danced or go into something else.

It was my choice and the other girls felt the same way. But I think that

we were exploited this way: We were underpaid. The waitresses were getting a lot of money from tips and what-not, than we did in dancing. But

then, we loved dancing and how are you going to dance when there are

no opportunities to, except that.96

Despite the Chinese community's condemnation and the compromises they had to make, Chinese American women continued to work

at the Forbidden City and other nightclubs through the 193os and

r94os. During its best years, the Forbidden City attracted one hundred

thousand customers a year, including senators, governors, and Hollywood stars like Ronald Reagan. By the time the World War II economy set in, more than a hundred Chinese American women were employed

in Chinatown's dozen nightclubs, and the composition of the audience

had changed from all white to half Chinese, indicating the attraction

that nightclub entertainment now held for middle-class Chinese Amer-

icans.97

In 1938, tourism in Chinatown was bringing in $5 million annually

and keeping many Chinese American women employed.98 The traffic

from the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition added to the Chinatown coffers and provided additional jobs for Chinese Americans. Merchants invested $1.z5 million to build a replica of a Chinese village at

the Treasure Island fairgrounds and organized parades and festivals in

Chinatown to attract tourists into the community. Two hundred positions opened up at the fairgrounds and another fifty in Chinatown. Young

women were particularly sought after to provide "atmosphere" during

the fair, serving as hostesses, secretaries, "cigarette girls," and waitresses.99

Even after the exposition ended in 1940, there was no decline in the

tourist trade in Chinatown. Moreover, the booming war economy that

followed not only ended the depression but also provided unprecedented

job opportunities for Chinese American women outside the local economy.

The depressed economy and government relief ultimately led to improved conditions for second-generation Chinese American women in

a number of other ways. Because of deflation, those who remained employed were able to stretch their salaries during the depression. "For a

dollar, my husband, myself, and my two children could enjoy a full dinner at the Far East Cafe," said Jane Kwong Lee. 100 Modern and affordable housing on the fringes of Chinatown was also more available to the

growing numbers of second-generation families. According to the

CSERA,

Since the economic depression of 1929, many of the houses of the Nob

Hill District were left vacant. The Chinese were willing to pay more than

the previous rent for houses in this district. As a result many a landlord

was willing to set aside prejudice for economic gain. Consequently, a large

number of residents are moving rapidly towards Nob Hill district. Fortyeight per cent of the properties occupied by Chinese west of Stockton

Street are owned by them. 101

This is not to say housing discrimination vanished during the depression years. Eva Lowe, for one, was rebuffed a number of times when she

tried to rent an apartment with her white girlfriend during the early 1 9 3 os. They would say yes to her girlfriend, but when they saw that Eva

was the roommate in question, they would renege, saying, "We don't

rent to Orientals." They finally found a place on Russian Hill-but only

after Eva claimed to be her friend's maid.'°2

Less affected by unemployment, a certain segment of the second generation continued their quest of the good life. As one Stanford student

told a news reporter in 193 6, "Certainly we want to live American lives;

we eat American foods, play bridge, go to the movies and thrill over

Clark Gable and Myrna Loy; we have penthouse parties, play football,

tennis and golf; attend your churches and your schools." 103 The social,

fashion, and sports pages of the Chinese Digest in the i 93 os give the impression that the depression was not an issue for the growing middle

class of young Chinese Americans. As the rest of the country recovered

from the hard times, certain young Chinese women in San Francisco were

competing in tennis, basketball, bowling, and track, learning the latest

dance, the Lambert Walk, going to the beauty parlor, and worrying about

what to wear to the next formal dance. Investigating the social life of

San Francisco Chinatown as a WPA worker, Pardee Lowe-a secondgeneration Chinese American himself-remarked on the good life he

saw in Chinatown, reflected in the "sleek-looking automobiles" that

crowded Chinatown's streets and the "flivvers operated by its collegiate

sons and daughters." 104

While local newspapers expressed concern about the second generation's fast pace of acculturation and self-indulgent ways, the need for

gender roles to keep up with modern times was also recognized. As Jane

Kwong Lee wrote in the Chinese Digest,

In spite of their frivolities in many ways, they [American-born Chinese]

show keen interest and thought in weighty questions of their age. Girls

no longer take marriage as the end of their career; they want to be financially independent just as much as all other American women. They

prepare themselves to meet all future emergencies. They study Chinese

in addition to English so that in case they go to China some day they will

be able to use the language.... Women in this community are keeping

pace with the quick changes of the modern world. The shy Chinese maidens in bound feet are forever gone, making place for active and intelligent young women.105

To guide them in making the necessary family and social adjustments,

Jane reoriented the YWCA program to serve their specific needs, just as

she had done for immigrant women. Adolescents were able to enjoy

sports, crafts, drama, dancing, and parties and take advantage of voca tional guidance and job training classes. Business and professional

women as well as young wives participated in Chinese language classes,

social dinners, recreational sports, and group discussions on topics such

as race prejudice, Chinese culture, current events, marital ethics, and child

rearing. Through these kinds of activities, the YWCA fulfilled its goal

of helping second-generation women develop socially, physically, morally,

and intellectually. The YWCA also encouraged them to expand their public roles by helping to raise funds for the Community Chest and participate in the Rice Bowl parades and opening celebrations of the Golden

Gate and Bay Bridges.

Spurred by economic and political conditions in the 1930s, the second generation did indeed assume a larger leadership role in the Chinese community, paralleling that of second-generation Mexican Americans in Los Angeles during this same period.106 The Chinese Digest,

founded in 193 5 by Thomas W. Chinn and Chingwah Lee as the voice

of this new generation, served as the clarion for social action. During

its five years of existence, the Chinese Digest unified Chinese Americans

across the country, encouraging them to act on the many social problems their community faced: poverty, health care, housing, employment,

child care, recreation, education, and political and workers' rights. For

its time, the Chinese Digest held a progressive perspective, advocating

tourism as a viable economic base for Chinatown and the ballot as the

political means by which to fight racial discrimination and improve living conditions. It also supported the war effort in China.

In contrast to CSYP, the Chinese Digest included many more news

and feature stories of interest to second-generation women. Clara Chan

had a regular column on women's fashion; Ethel Lum wrote on sociological topics, including women's issues; and P'ing (Alice Fong) Yu's

"Jade Box" featured women's fashions, recipes, and social as well as political news. Taken as a whole, the articles reflected the effects of acculturation on the social consciousness of second-generation women, some

of whom became political activists during the depression years. Tracing

the development of two such women, Eva Lowe and Alice Fong Yu,

sheds light on how some Chinese American women, inspired by the political temper of the 193os, became more active in community reform,

electoral politics, and Chinese nationalism.

Eva Lowe, who had followed her brother-in-law and sister to China

in 1919 at the age of ten, returned to San Francisco a changed person

four years later. "In China," she said, "I went to Chinese school and I

learned about Chinese history, from the Tang dynasty through the end of the Qing dynasty and how the imperialist countries took over China.

Like Dr. Sun Yat-sen said, China was cut up like a watermelon and each

European imperialist country had a piece of it. I remember thinking,

you know, China used to be so strong, and now this; and I cried in

class."107 Other incidents-the mistreatment of her mother by her

grandmother because she did not bear sons, the banning of her stepmother from the village because a man was seen entering her room, and

a chance meeting with a female scholar who first introduced her to feminism and socialism-alerted her to the unfair treatment of Chinese

women and the need to fight back by becoming politically active.