Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (40 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Upon her return to San Francisco she attended high school and became involved with the Chinese Students Association, which claimed a

membership of three thousand.10s What appealed to her was the group's

anti-imperialist stance and concern for China's future. She did not hesitate to join in making "soap box" speeches in Chinatown condemning

Japanese aggression in China. "People still recall the slogan I coined, `If

you have money, give money. If you have muscles, give muscles. I have

neither money or muscles, but I can give my voice [to the cause],"' she

said.109 Wanting to do her part to help the disadvantaged, Eva assisted

families in applying for relief during the depression and joined the

Huaren Shiyi Hui in demanding action from the Chinese Six Companies on behalf of the unemployed. She also supported the longshoremen's strike and participated in the hunger march in San Francisco,

shouting, "We want work! We want work!" with the masses of people

pouring down Market Street to City Hall. Because these groups were

ostracized by the community as Communist, her friends dropped out

one by one owing to parental pressure, but Eva remained active in leftist politics until she married and left for Hong Kong with her husband

and son in 1937. "I always believed in fighting for the underdog," she

reflected years later.11°

While Chinese nationalism was what motivated Eva Lowe to engage

in politics, Alice Fong Yu, the first Chinese American schoolteacher in

the San Francisco public schools, was influenced to contribute to the

community by her family upbringing as well as Christianity. 111 "Hoga

gow [good family training]- that's what my parents gave me," said Alice. Growing up in Washington (Nevada County), California, she became aware early on of racial discrimination:

It is surprising, isn't it, that [in] just a small one-room school and [among]

just a handful of children, they still thought we were queer. They would

sing "Ching Chong Chinaman" and all those things to make fain of us and make you feel like nobody, and then when we would play games,

they wouldn't hold our hands, as if they would be contaminated by our

hands, and so they wouldn't accept us.

The Fong children, disappointed and hurt, sought comfort from their

parents, who told them, "You shouldn't let those things bother you, because they are just barbarians; that's why they treat you like that. You

have culture. Our people have a long history. Wait until you get your

education and go back to China, where they will look up to you. But

these people are barbarians; don't let them worry you."

Although their white classmates shunned them and the teachers made

them feel inferior, the church welcomed them into its fold, sending a

Sunday school teacher to Vallejo Chinatown, where the family had moved

in 1923, to teach the children the Bible and take them to Christian retreats. "The Christians were the ones who accepted us in the early days,"

Alice said, and "gave us a chance to intermingle with other races." Encouraged both by her parents and by her involvement in the YWCA Girls

Reserve, Alice became a community activist after she moved to San Francisco. During the 193os, Alice was involved with many Chinatown organizations, including the Square and Circle Club, YWCA, Chinese

Needlework Guild, and Tahoe Christian Conference. A founding member of the Square and Circle Club, Alice helped raise funds for Chinese

orphans, the elderly, and needy families. She also worked with other community organizations to register American-born Chinese to vote, campaign for the reelection of Congresswoman Florence Kahn, and lobby

for improved housing and recreational facilities in Chinatown. Alice became particularly well known in the community for planning and coordinating Square and Circle fashion shows as fund-raisers and leading the

boycott against the wearing of silk stockings during the War of Resistance Against Japan (11937-45). In her capacity as a teacher at Commodore Stockton Elementary School, she also helped found the Chinese chapter of the Needlework Guild, which provided clothing and

shoes to needy children in Chinatown. 112 "The mothers couldn't speak

English well enough to join the P.T.A., so we started our own group,"

she explained. "We got together to sew and talk about things. Whenever we found out about an impoverished family, we would help them

get on welfare."' 13

In 1933, Alice joined with Ira Lee and Edwar Lee to organize the

first Lake Tahoe Chinese Young People's Christian Conference, in

which second-generation Chinese from all over California came together

to discuss common problems and concerns. According to Ira, he, Al ice, and Edwar hoped to duplicate the social gospel spirit and fellowship

that so moved them at YMCA conferences. They also wanted to provide a place for young Chinese Americans from different church denominations to meet outside of Chinatown. What started as an experimental retreat at the Presbyterian conference grounds at Zephyr Point,

Lake Tahoe, continued as an annual conference until the i96os. At the

beginning, topics of discussion focused on Christianity and the situation in China. Then in the later 1930S, as the group grew to more than

one hundred participants, including some non-Christians, interest turned

to discrimination, marriage and family life, political involvement, community problems, and the question of serving China. Resolutions were

passed calling for increased social integration, vocational guidance, involvement in American politics, adoption of Western-style marriages and

family life, and recreational interests beyond mah-jongg and dancing.

Although the discussions lacked structure or follow-through, the retreats

provided the second generation with an opportunity to socialize, share

views, and vent frustrations. The benefits accrued were less to the church

or the community as to the individual participants, who learned new organizational skills and carried the ideas for and commitment to social

change back to their respective communities. One offshoot of the Tahoe

Conference was the Chinese Young People's Forum, an interdenominational group started by Alice that met weekly at Cameron House to

continue discussing ways to solve the community's problems. 114

Thus, although the depression was a time of economic strife for most

of America, for a significant number of Chinese women in San Francisco it was a time of stable employment, social growth, and political activism. This positive side became even more evident when Chinese

women went on strike for the first time against the National Dollar Stores,

the largest garment factory in Chinatown.

Joining the Labor Movement:

The 19 3 8 Garment Workers' Strike

Chinese women's hard-won victory in their strike against

National Dollar Stores was due as much to their determination for social change in the workplace as to the economic and political circumstances of the depression that nurtured their union activism. Their ability to sustain a strike for ro5 days, supported by a white labor union as well as left organizations in Chinatown, proved that Chinese women

could stand up for themselves and work across generational, racial, gender, and political lines to gain better working conditions in Chinatown.

Although little was gained in terms of higher wages and job security (the

factory closed a year after the strike), the experience moved women well

beyond the domestic sphere into the political arena: it raised their political consciousness and organizing skills, allowed them to become part

of the labor movement and to find jobs outside Chinatown, and, most

important, marked their first stand against labor exploitation in the garment industry. The strike also provides insights into the class and gender dynamics of ethnic enterprises and the possibilities of organizing Chinese women workers in the garment industry.

In 193 8, when the strike against National Dollar Stores was launched,

the garment industry was the largest employer in Chinatown. More than

one thousand women worked in sixty-nine garment factories in Chinatown. Most of these factories were small, with fewer than fifty employees toiling under sweatshop conditions: poor lighting and ventilation,

long hours, low wages. All were nonunion and operating on a piecerate basis, earning wages ranging from $4 to $16 a week-as compared

to union workers who received from $19 to $3o a week for a shorter

workweek.' 15 Ben Fee, a labor organizer and Communist Party member, stated in CSYP that Chinatown's garment industry had reached a

crisis situation in part because of the depression, but more so because

small contractors with inadequate capital and unsound management practices persisted in underbidding each other and cutting workers' salaries

in order to compete in the highly seasonal industry. As a result, he pointed

out, there was a high turnover and shortage of skilled labor, the stiff

market competition allowed jobbers to keep contract prices low, and factories proved unable to meet NRA labor standards. He advocated that

Chinese contractors unite to eliminate competition among themselves

and that workers organize to improve their own lives. He also had the

foresight to call for ethnic unity across class lines: "Overseas Chinese, be

they factory owners or workers, are all living under the economic repression of another race, so we should work together to come up with

a long-term plan that will enable us to co-exist with each other."' 16 Needless to say, he was not heeded.

Unlike other Chinatown garment shops, National Dollar Stores,

which employed i z 5 Chinese workers, mostly women, was vertically integrated; that is, it controlled all aspects of production, from manufacturing to contracting out to retailing. Owned by Joe Shoong, one of the wealthiest Chinese businessmen in the country, the National Dollar

Stores factory specialized in women's light apparel for exclusive distribution to National Dollar Stores' thirty-seven retail outlets on the West

Coast. In 1937, gross sales for the chain amounted to $7 million, and

profits to about $170,000. Joe Shoong's salary that year was $141,000,

with dividends earning him another $40,000. Known as a generous philanthropist in the Chinatown community, he lived in a large stucco house

in Oakland, had five cars, and was a Shriner as well as a thirty-seconddegree Mason.''7

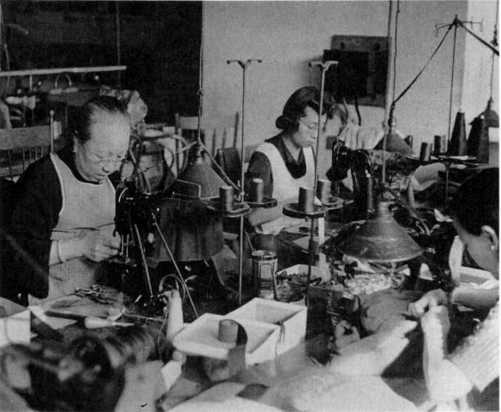

Garment workers in San Francisco Chinatown. (Courtesy of Labor Archives

and Research Center, San Francisco State University)

In all of Chinatown, Joe Shoong's factory was the cleanest and most

modern, and it offered the best wages-supposedly $13.3 3 for a fortyeight-hour week, the minimum rate in California. The strike came about

only after many frustrating attempts by workers to negotiate steady employment and increased wages. "Wages was the main issue," recalled Sue

Ko Lee, who was a buttonhole machine operator at National Dollar Stores before the strike. "That time the [minimum] wage law was already in, but we weren't getting that. We didn't keep the hours according

to law. And there was already a homework rule but they were sending

work out to homeworkers."lls According to Jennie Matyas, labor organizer for the ILGWU at the time, the workers first approached the

union for help in 1937.

Japan and China were at war. Most of the Chinese here had relatives back

home. They all felt very loyal to their home relatives and wanted to support them. [Yet] the workers in the National Dollar factory found themselves underbid by other workers in Chinatown. They found that the work

went to other Chinese contractors who did the work cheaper than they

did. . . . They decided to supplicate the owner to remember that they

needed money to send home to China and wouldn't he provide them

with more work.119

Unable to get a positive response from the factory owner, garment workers decided to organize themselves. This was the moment the ILGWU

had been waiting for, because tip to that point they had been unsuccessful in organizing the Chinese.

In San Francisco, where Chinese dominated the garment industry and

often underbid union shops on contracts with downtown manufacturers, the strategy the ILGWU adopted was to organize and control the

Chinese or drive them out of business. "The situation is getting more

desperate," Matyas told the Chinese Digest, "and if the Chinese contractors and dressmakers do not heed the writing on the wall and organize, it is possible that the American garment workers, backed by the

ILGWU, may declare war on the Chinese garment industry." The Digest, recognizing the veiled threat behind the labor union's determination to organize Chinatown workers, stressed that the community could

no longer afford to remain outside the labor movement: