Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (35 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

With Harris in place, Louie loitered by the Quack’s office, waiting for his moment. The Quack and the guards stepped out, cigarettes in hand. Louie crept around the side of the building, dropped onto al fours so that he wouldn’t be seen through the windows, and crawled into the office. The newspaper was stil there, sitting on the desk. Louie snatched the paper, stuck it under his shirt, then crawled back out, rose to his feet, and walked to Harris’s cel , striding as quickly as he could without attracting attention. He opened the paper and showed it to Harris, who stared at it for several seconds. Then Louie crammed it under his shirt again and sped back to the Quack’s office. His luck had held; the Quack and the guards were stil outside. He went back down on al fours, hurried in, threw the paper on the desk, and fled. No one had seen him.

At the barracks, Harris pul ed out a strip of toilet paper and a pencil and drew the map. The men al looked at it. Memories later differed as to the subject of the map, but everyone recal ed that it showed Al ied progress. Harris hid the map among his belongings.

In the late afternoon of September 9, Harris was sitting in a cel with another captive, discussing the war, when the Quack swept into the doorway. Harris hadn’t heard him coming. The Quack noticed something in Harris’s hand, stepped in, and snatched it. It was the map.

The Quack studied the map; on it, he saw the words “Philippine” and “Taiwan.” He demanded that Harris tel him what it was; Harris replied that it was idle scribbling. The Quack wasn’t fooled. He went to Harris’s cel , ransacked it, and found, by his account, a trove of hand-drawn maps—some showing air defenses of mainland Japan—as wel as the stolen newspaper clipping and the dictionary of military terms. The Quack cal ed in an officer, who spoke to Harris, then left. Everyone thought that the issue was resolved.

That night, the Quack abruptly cal ed al captives into the compound. He looked strange, his face crimson. He ordered the men to do push-ups for about twenty minutes, then adopt the Ofuna crouch. Then he told Harris to step forward. Louie heard the marine whisper, “Oh my God. My map.”

The men who witnessed what fol owed would never blot it from memory. Screeching and shrieking, the Quack attacked Harris, kicking him, punching him, and clubbing him with a wooden crutch that he took from an injured captive. When Harris col apsed, his nose and shins streaming blood, the Quack ordered other captives to hold him up, and the beating resumed. For forty-five minutes, perhaps an hour, the beating went on, long past when Harris fel unconscious. Two captives fainted.

Harris’s handmade Japanese-English dictionary, discovered by Sueharu Kitamura, “the Quack.” Courtesy of Katherine H. Meares The Quack. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

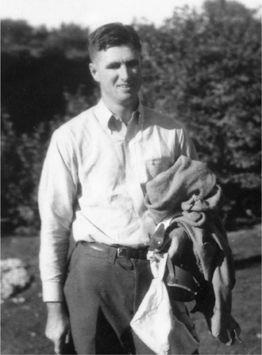

Wil iam Harris. Courtesy of Katherine H. Meares

At last, raindrops began to patter over the dirt, the Quack, and the body beneath him. The Quack paused. He dropped the crutch, walked to a nearby building, leaned against its wal , and slid languidly to the ground, panting.

As the guards dragged Harris to his cel , Louie fol owed. The guards jammed Harris in a seated position against a wal , then left. There Harris sat, eyes wide open but blank as stones. It was two hours before he moved.

Slowly, in the coming days, he began to revive. He was unable to feed himself, so Louie sat with him, helping him eat and trying to speak with him, but Harris was so dazed that he could barely communicate. When he final y emerged from his cel , he wandered through camp, his face grotesquely disfigured, his eyes glassy. When his friends greeted him, he didn’t know who they were.

——

Three weeks later, on the morning of September 30, 1944, the guards cal ed the names of Zamperini, Tinker, Duva, and several other men. The men were told that they were going to a POW camp cal ed Omori, just outside of Tokyo. They had ten minutes to gather their things.

Louie hurried to his cel and lifted the floorboard. He pul ed out his diary and tucked it into the folds of his clothing. At a new camp, a body search would be inevitable, so he left his other treasures for the next captive to find. He said good-bye to his friends, among them Harris, stil floating in concussed misery. Sasaki bid Louie a friendly farewel , offering some advice: If interrogated, stick to the story he’d told on Kwajalein. A few minutes later, after a year and fifteen days in Ofuna, Louie was driven from camp. As the truck rattled out of the hil s, he was euphoric. Ahead of him lay a POW camp, a promised land.

Twenty-three

Monster

IT WAS LATE MORNING ON THE LAST DAY OF SEPTEMBER 1944. Louie, Frank Tinker, and a handful of other Ofuna veterans stood by the front gate of the Omori POW camp, which sat on an artificial island in Tokyo Bay. The island was nothing more than a sandy spit, connected to shore by a tenuous thread of bamboo slats. Across the water was the bright bustle of Tokyo, stil virtual y untouched by the war. Other than the patches of early snow scattered over the ground like hopscotch squares, every inch of the camp was an ashen, otherworldly gray, reminding one POW of the moon. There were no birds anywhere.

They were standing before a smal office, where they’d been told to wait. In front of them, standing beside the building, was a Japanese corporal. He was leering at them.

He was a beautiful y crafted man, a few years short of thirty. His face was handsome, with ful lips that turned up slightly at the edges, giving his mouth a faintly cruel expression. Beneath his smartly tailored uniform, his body was perfectly balanced, his torso radiating power, his form trim. A sword angled elegantly off of his hip, and circling his waist was a broad webbed belt embel ished with an enormous metal buckle. The only incongruities on this striking corporal were his hands—huge, brutish, animal things that one man would liken to paws.

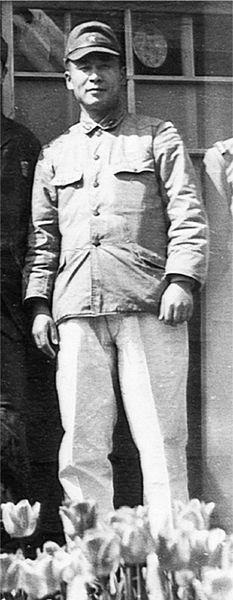

Mutsuhiro Watanabe, “the Bird.” National Archives

Louie and the other prisoners stood at attention, arms stiff, hands flat to their sides. The corporal continued to stare, but said nothing. Near him stood another man who wore a second lieutenant’s insignia, yet hovered about the lower-ranking corporal with eager servility. Five, perhaps ten minutes passed, and the corporal never moved. Then, abruptly, he swept toward the prisoners, the second lieutenant scurrying behind. He walked with his chin high and his chest puffed, his gestures exaggerated and imperious. He began to inspect the men with an air of possession—looking them over, Louie thought, as if he were God himself.

Down the line the corporal strode, pausing before each man, raking his eyes over him, and barking, “Name!” When he reached Louie, he stopped.

Louie gave his name. The corporal’s eyes narrowed. Decades after the war, men who had looked into those eyes would be unable to shake the memory of what they saw in them, a wrongness that elicited a twist in the gut, a prickle up the back of the neck. Louie dropped his eyes. There was a rush in the air, the corporal’s arm swinging, then a fist thudding into Louie’s head. Louie staggered.

“Why you no look in my eye?” the corporal shouted. The other men in the line went rigid.

Louie steadied himself. He held his face taut as he raised his eyes to the corporal’s face. Again came the whirling arm, the jarring blow into his skul , his stumbling legs trying to hold him upright.

“You no look at me!”

This man, thought Tinker, is a psychopath.

——

The corporal marched the men to a quarantine area, where there stood a rickety canopy. He ordered the men to stand beneath it, then left.

Hours passed. The men stood, the cold working its way up their sleeves and pant legs. Eventual y they sat down. The morning gave way to a long, cold afternoon. The corporal didn’t come back.

Louie saw a wooden apple box lying nearby. Remembering his Boy Scout friction-fire training, he grabbed the box and broke it up. He asked one of the other men to unthread the lace from his boot. He fashioned a spindle out of a bamboo stick, fit it into a hole in a slat from the apple box, wound the bootlace around the spindle, and began alternately pul ing the ends, turning the spindle. After a good bit of work, smoke rose from the spindle. Louie picked up bits of a discarded tatami mat, laid them on the smoking area, and blew on them. The mat remnants whooshed into flames. The men gathered close to the fire, and cigarettes emerged from pockets. Everyone got warmer.

The corporal suddenly reappeared. “Nanda, nanda!” he said, a word that roughly translates to “What the hel is going on?” He demanded to know where they’d gotten matches. Louie explained how he had built the fire. The corporal’s face clouded over. Without warning, the corporal slugged Louie in the head, then swung his arm back for another blow. Louie wanted to duck, but he fought the instinct, knowing from Ofuna that this would only provoke more blows. So he stood stil , holding his expression neutral, as the second swing connected with his head. The corporal ordered them to put the fire out, then walked away.

Louie had met the man who would dedicate himself to shattering him.

——

The corporal’s name was Mutsuhiro Watanabe.* He was born during World War I, the fourth of six children of Shizuka Watanabe, a lovely and exceptional y wealthy woman. The Watanabes enjoyed a privileged life, having amassed riches through ownership of Tokyo’s Takamatsu Hotel and other real estate and mines in Nagano and Manchuria. Mutsuhiro, whose father, a pilot, seems to have died or left the family when Mutsuhiro was relatively young, grew up on luxury’s lap, living in beautiful homes al over Japan, reportedly waited on by servants and swimming in his family’s private pool. His siblings knew him affectionately as Mu-cchan.

After a childhood in Kobe, Mutsuhiro attended Tokyo’s prestigious Waseda University, where he studied French literature and cultivated an infatuation with nihilism. In 1942, he graduated, settled in Tokyo, and took a job at a news agency. He worked there for only one month; Japan was at war, and Mutsuhiro was deeply patriotic. He enlisted in the army.

Watanabe had lofty expectations for himself as a soldier. One of his older brothers was an officer, and his older sister’s husband was commander of Changi, a giant POW camp in Singapore. Attaining an officer’s rank was of supreme importance to Watanabe, and when he applied to become an officer, he probably thought that acceptance was his due, given his education and pedigree. But he was rejected; he would be only a corporal. By al accounts, this was the moment that derailed him, leaving him feeling disgraced, infuriated, and bitterly jealous of officers. Those who knew him would say that every part of his mind gathered around this blazing humiliation, and every subsequent action was informed by it. This defining event would have tragic consequences for hundreds of men.

Corporal Watanabe was sent to a regiment of the Imperial Guards in Tokyo, stationed near Hirohito’s palace. As the war hadn’t yet come to Japan’s home islands, he saw no combat. In the fal of 1943, for unknown reasons, Watanabe was transferred to the military’s most ignominious station for NCOs, a POW camp. Perhaps his superiors wanted to rid the Imperial Guards of an unstable and venomous soldier, or perhaps they wanted to put his volatility to use. Watanabe was assigned to Omori and designated the “disciplinary officer.” On the last day of November 1943, Watanabe arrived.

——

Even prior to Watanabe’s appearance, Omori had been a trying place. The 1929 Geneva Convention, which Japan had signed but never ratified, permitted detaining powers to use POWs for labor, with restrictions. The laborers had to be physical y fit, and the labor couldn’t be dangerous, unhealthy, or of unreasonable difficulty. The work had to be unconnected to the operations of war, and POWs were to be given pay commensurate with their labor.

Final y, to ensure that POW officers had control over their men, they could not be forced to work.

Virtual y nothing about Japan’s use of POWs was in keeping with the Geneva Convention. To be an enlisted prisoner of war under the Japanese was to be a slave. The Japanese government made contracts with private companies to send enlisted POWs to factories, mines, docks, and railways, where the men were forced into exceptional y arduous war-production or war-transport labor. The labor, performed under club-wielding foremen, was so dangerous and exhausting that thousands of POWs died on the job. In the extremely rare instances in which the Japanese compensated the POWs for their work, payment amounted to almost nothing, equivalent to a few pennies a week. The only aspect of the Geneva Convention that the Japanese sometimes respected was the prohibition on forcing officers to work.