unSpun

Contents

Chapter 1

From Snake Oil to Emu Oil

Chapter 2

A Bridesmaid's Bad Breath

Warning Signs of Trickery

Chapter 3

“Tall” Coffees and Assault Weapons

Tricks of the Deception Trade

Chapter 4

UFO Cults and Us

Why We Get Spun

Chapter 5

Facts Can Save Your Life

Chapter 6

The Great Crow Fallacy

Finding the Best Evidence

Chapter 7

Osama, Ollie, and Al

The Internet Solution

For Beverly and Bob

Introduction

A World of Spin

W

E LIVE IN A WORLD OF SPIN.

It flies at us in the form of misleading commercials for products and political candidates and about public policy matters. It comes from businesses, political leaders, lobbying groups, and political parties. Millions are deceived every day, buying products, voting for candidates, supporting policies and even warsâall because of spin.

“Spin” is a polite word for deception. Spinners mislead by means that range from subtle omissions to outright lies. Spin paints a false picture of reality by bending facts, mischaracterizing the words of others, ignoring or denying crucial evidence, or just “spinning a yarn”âby making things up.

Some degree of spin can be considered harmless, as when a person puts his best foot forward in hopes that we won't notice that the other shoe may be a bit scuffed. But we're not writing here about mere puffery, nor are we criticizing advocates who argue strongly and honestly for their side; we're talking about outright dishonesty, misrepresentation, and a lack of respect for facts. We see these far too commonly today in politics and business alike.

Spin is tolerated and even admired in some circles. In Washington, a good spin doctor is lauded, much like a twenty-game winner in baseball. But we believe voters and consumers need to recognize spin when it is used against them, just as good batters spot the spin on a curveball. If they don't recognize spin, they risk not only buying the wrong cold remedy or the wrong car but also going into the voting booth with false notions in their heads about the candidates.

Spin misleads people about matters as trivial as a jar of beauty cream or as deadly serious as cancer. Readers may find our examples variously outrageous and amusing, but we hope all of them are instructive. Our purpose in writing this book is to give readers some tools for recognizing and avoiding spin, and finding solid facts.

Both parties spin, but we'll start, arbitrarily, with a Republican example. To illustrate what we mean when we say that spin is deception, consider an appearance of Karl Rove, senior adviser to President George W. Bush, at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., on May 15, 2006. Rove gave a vigorously upbeat picture of the American economy, and nothing he said was absolutely false, yet the overall impression he tried to create was at times so divorced from reality as to seem unhinged.

Rove said, for example: “Real disposable income has risen almost 14 percent since President Bush took office. The Dow Jones industrial average is near its all-time high. And since the 2003 tax cuts have been passed, asset values, including homes and stocks, have grown by $13 trillion.”

All that was true, and a listener might well have concluded that the income of every American had risen. But Rove failed to mention that since Bush took office, poverty had worsened significantly, millions of workers had lost their health insurance, and real wages were stagnant for rank-and-file payroll employees. The “real disposable income” he cited was a statistic that measures the total increase in income, not how that increase is distributed. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, real income (after inflation) for the typical U.S. household had fallen by 3.6 percent during Bush's first four years in officeâa loss of $1,670 in 2004 dollars. The income gains of which Rove spoke were going almost exclusively to those in the upper half of society, the same affluent households that owned the stocks, bonds, and expensive homes whose values had grown so dramatically.

Democrats engage in similar behavior. In fact, two weeks after Rove's speech, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the economy had added another 75,000 jobs in the previous month and that the unemployment rate had dropped to 4.6 percent. And yet the Democratic National Committee called the results “more evidence of President Bush's failed economic record,” saying economists had expected a somewhat larger job gain. In fact, the unemployment rate was the lowest in five years, well below the average for all months of the Clinton administration (which was 5.2 percent), and a full percentage point lower than the average for all months since World War II. Thus in the hands of a partisan spinmeister, a better-than-average unemployment rate becomes a failure.

Don't be tempted to dismiss this sort of thing as a mere difference of interpretation or an argument over whether the economic glass is half full or half empty. There is more to it than that. Both sides are actively working to deceive the public. They may even be deceiving themselves to a large degree, and we often see reason to suspect that's the case. Both sides tend to ignore evidence that doesn't favor their point of view and to avoid tough problems by spinning them away and hoping voters won't notice.

We sometimes see this more easily in the world of advertising, where corporate snake-oil salesmen routinely employ spin to get us to buy their products. In this book we'll tell you of an over-the-counter pain reliever that claimed to be “prescription strength” when it was

half

the usual prescription dose, and an Internet service marketed as having “broadband-like speed” when in fact cable modems are several times faster. But as obvious as some advertising deceptions may seem to some of us, they fool any number of people into spending untold hundreds of millions of dollars each year on products that don't perform as advertised. We'll tell you about some well-known products whose sales have been built almost entirely on deception. Advertisers keep spinning because it is profitable to do so.

Spin comes at us today in ways that didn't even exist a decade or so ago. On cable-news talk shows, advocates issue torrents of factual claims daily, seldom challenged by their amiable hosts. And the Internet has enabled a potent new weapon of deception, so-called viral marketing of falsehoods that replicate and spread like a disease. One such message during the 2004 campaign claimed that President Bush secretly planned to reinstitute a military draft if he was reelected. Another claimed that John Kerry's wife was responsible for sending thousands of U.S. jobs overseas. Both were false, but millions of voters believed them. For example, 42 percent of the people we polled immediately after the 2004 election considered it either “somewhat” or “very” truthful that Bush would reinstitute the draft.

We simply can't always count on government regulators, courts, or the news media to sort through the daily barrage of baloney. This book is about how to become

un

spun. We'll explain how to recognize spin, how to understand its nature, and how to spot the techniques spinners use to deceive. We'll show you what years of communications research and advances in human psychology have taught us about why even the most intelligent people are susceptible to being spun. We'll show you how staying unSpun can save your life, not to mention your money and your self-respect.

We'll also show you how, for all the faults of the Internet, you can use it to find reliable information with a few keystrokes, at home, for free, while avoiding misinformation and fraud. And we'll offer some methods for properly weighing and evaluating evidence and reaching your own well-founded conclusions.

We'll share with you the tools that we found useful as we created the Annenberg Public Policy Center's FactCheck.org, a political website designed to be a “consumer advocate” for voters. FactCheck.org got nine million visits during its first two years of operation from citizens seeking help to sort through the deception and confusion in U.S. politics.

A word of caution: if you are a strong partisan just looking to prove the other side is wrong, this book will challenge you to cast the same critical eye on your own beliefs as you do on the other side's. Doing so will not be easy. Research we will introduce later in the book shows that partisans often become accomplices to their own deception by rejecting information, valid or not, merely because it conflicts with their existing beliefs. If you are a bitter cynic who has concluded that nobody is telling the truth, and you have given up looking for facts, we will show you why you don't need to resign yourself to a world of spin.

Avoiding spin and finding solid information can be a challenge, perhaps more than most people realize. Not only are we surrounded by commercial and political pitchmen who are trying their best to pull the wool over our eyes, but also our own brains betray us in ways that psychologists are still struggling to understand. We'll explain how our own biology can blind us to accurate information, and why it is important to work constantly at taking a skeptical approach to advertising and at keeping our minds open to the possibility that, just maybe, the other person has a point.

We hope you'll emerge from this book rightly skeptical of the many dubious claims you read and hear, but willing to consider all the available evidence. We think you

can

tell who's right and who's wrong most of the time, if you are willing to keep an open mind and to put in a bit of effort. And we'll show you how to have some fun doing it.

We take as our motto something the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York was fond of saying: “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are

not

entitled to your own

facts

.”

Chapter 1

From Snake Oil to Emu Oil

A

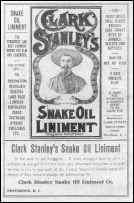

CENTURY AGO A SELF-PROCLAIMED COWBOY NAMED

C

LARK

S

TANLEY

, calling himself the Rattlesnake King, peddled a product he called Snake Oil Liniment. He claimed it was “good for man and beast” and brought immediate relief from “pain and lameness.” Stanley sold it for 50 cents a bottleâthe equivalent of more than $10 todayâas a remedy for rheumatism, toothache, sciatica, and “bites of animals, insects and reptiles,” among other ailments. To promote his pricey cure-all, Stanley publicly slaughtered rattlesnakes at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.

Stanley was the most famous of the snake-oil salesmen, back before passage of the federal Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. And he was a fraud. When the federal government finally got around to seizing some of Stanley's product in 1915, the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Chemistry (forerunner of today's Food and Drug Administration) determined that it “consisted principally of a light mineral oil (petroleum product) mixed with about 1 per cent of fatty oil (probably beef fat), capsicum, and possibly a trace of camphor and turpentine.” And no actual snake oil. Stanley was charged with violating the federal food and drug act. He didn't contest the charge and was fined $20.

Are today's pitchmen and hucksters any less deceptive? We don't think so. “Snake oil” has a bad name these days (at least in the United States; in China, it is used to relieve joint pain). But in 2006 we found another animal-oil product thatâaccording to its marketerâis “much better than Botox! [and] Makes Wrinkles Almost Invisible to the Naked Eye!â¦Look as much as 20-years youngerâ¦in less than one minute.” The maker even claims that the product won't just hide wrinkles, with repeated use it may eliminate them: “It is possible your wrinkles will no longer even exist.” The name of the product is Deception Wrinkle-Cheating Cream. How appropriate.

An undated poster, believed to be from around 1905, advertising Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment, which consisted mainly of mineral oil and contained no snake oil at all.

According to Planet Emu, the marketer, this scientific miracle contains “the only triple-refined emu oil in the world,” but we quickly determined that this product is nothing more than triple-refined hokum. Emus are those big, flightless Australian birds; the oil is said to be an ancient Aboriginal remedy. But when we asked Planet Emu for proof of their claims, they cited only one scientific study of emu oil's cosmetic properties, and it had nothing to do with wrinkles. It found that emu oil was rated better than mineral oil as a moisturizer by

eleven

test subjects. We searched the medical literature for ourselves and found some scanty evidence that emu oil may promote healing of burns in rats. We found no testing of emu oil as a wrinkle cream, much less any testing that compared it with Botox.

That's where a century of progress in product promotion has gotten us: from baseless claims for snake oil to baseless claims for emu oil. The products change, but the techniques of deception (small “d”) are as underhanded now as they were in the days of Clark Stanley. Meanwhile the price has gone up. “Deception” emuo-il wrinkle cream, at $40 for three quarters of an ounce, costs four times more than a bottle of its snake-oil forebear, even after adjusting for a century of inflation.

Bunk is fairly typical of beauty products. “All the cosmetics companies use basically the same chemicals,” a former cosmetics chemist, Heinz J. Eiermann, told

The Washington Post

way back in 1982. “It is all the same quality stuff.” Eiermann was then head of the Food and Drug Administration's division of cosmetics technology. His conclusion: “Much of what you pay for is make-believe.”

Cosmetics advertising is just one example of the rampant deception that surrounds us. Spin pervades both commerce and politics, and most of it is not so funny. As we'll soon see, any number of products with household names are marketed with false or deceptive advertising. Whole companies have been built on such deception. Elections have been decided by voters who believed false ideas fed to them by manipulative television ads and expressed in “talking points,” and if you voted for a presidential candidate in 2004 the odds are you were one of them. The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq wasn't the first American war fought with the passionate support of a public that believed claims about the enemy that turned out to be false.

We've found that whether the spin is political, commercial, or ideological, and whether the stakes are trivial (as with $40 wrinkle remedies) or, quite literally, life and death, the ways by which we are deceived are consistent and not so hard to recognize. The first step in confronting spin is to open our eyes to how often we encounter it. It's so common, so all-pervading, that we can't avoid it.

Prescription-Strength Malarkey

Some examples from commercial advertising:

⢠Bayer HealthCare once advertised Aleve pain medication as “Prescription Strength Relief Without a Prescription.” It wasn't. The maximum recommended dose of Aleve is less than half the usually prescribed dose of Anaprox, a prescription counterpart.

⢠Munchkin, Inc., said of one of its products: “Baby bottles like Tri-Flow have been clinically shown to reduce colic.” But look behind the “clinically proven” claim and you find the test was of a competitor's similar bottle, not Munchkin's.

⢠NetZero claimed its dial-up Internet service allows users to “surf at broadband-like speeds.” It doesn't. Cable modems are several times faster.

⢠Tropicana claimed in TV ads that drinking two to three glasses a day of its “Healthy Heart” orange juice could reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke. The Federal Trade Commission said those claims weren't supported by scientific evidence, and prohibited the company from repeating the claims in future ads.

Political Snake Oil

Deceptive product promotion is a minor problem compared with political spin. Compare claims for snake oil and emu oil with those routinely made about crude oilâpetroleum. In the 2004 presidential campaign, both John Kerry and President George W. Bush spoke to voters of making America “energy independent.” Toward the end of the campaign, Professor Robert Mabro, who was then the director of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, told

The New Yorker

magazine: “The two candidates, with due respect, are lying to the people, or they don't know what they are talking about.”

Our guess is that Bush and Kerry knew exactly what they were talking about. Actually achieving “energy independence” would require huge changes that neither man cared to propose. One independent study, by the Rocky Mountain Institute, projected that the United States could eliminate the need to import any oil from abroad by 2040, if we took such measures as a heavy tax on gas-guzzling vehicles, a federal program to buy and scrap old gas-gulping clunkers, and generous subsidies from taxpayers to help low-income persons buy more fuel-efficient autos. The projected cost of such measures was $180 billion, at least $150 billion more than either Kerry or Bush had pledged, and even so it is probably far too little. Others say that what's required for independence is a government program on the scale of the project that produced the Apollo moon landings.

Sure enough, oil imports continued to rise after Bush was sworn in for a second term, so much that in 2005 the United States imported 59.8 percent of the oil it consumed, up from 58.4 percent in 2004. The increase came despite enactment of a Bush-backed energy bill, which was predicted only to slow the growth of imports modestly, not to reverse it.

The crude-oil spin continues. In his 2006 State of the Union address, the president said the United States was “addicted to oil.” But this time he set a more modest goal: cutting imports from Middle Eastern countries by 75 percent. That was less deceptive than speaking of “independence,” but deceptive nonetheless. Only about one barrel of imported oil in every five was coming from the Middle East, so cutting that by 75 percent sounded like a bigger step than it really was. The biggest suppliers to the United States actually were Canada and Mexico.

In his speech to Congress, Bush proposed a mere 22 percent increase in government spending for clean-energy research, called “shockingly small” by Severin Borenstein, an energy economist at the University of CaliforniaâBerkeley. This expert added that Bush's plan was “hardly the Manhattan Project equivalent on energy that we need.”

It comes as no surprise that candidates want to avoid discussing politically painful solutions during an election year, or ever. But there's real harm in pretending that there are easy solutions to big problems, or that the problems don't exist. Accepting the spin means letting the problems fester; meanwhile, the solutions become even more painful, or the problems overwhelm us entirely.

The Profits of Disinformation

Deception is highly profitable. Consider the case of one California huckster calling himself “Dr.” Alex Guerrero. He appeared on TV infomercials claiming that his “natural” herbal remedy Supreme Greens (containing grapefruit pectin) could cure or prevent cancer, arthritis, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, heart disease, diabetes, heartburn, fatigue, or even “the everyday ravages of aging,” all while promoting weight loss of up to four pounds per week and up to eighty pounds in eight months. A one-month supply cost $49.99, plus shipping and handling. And as incredible as “Dr.” Guerrero's claims might seem, he sold enough Supreme Greens to drive around in a Cadillac Escalade. When the Federal Trade Commission hauled him into court he agreed to settle the case by halting his claims and either paying a $65,000 fine or giving the government title to his flashy SUV. And he was just one small-timer in the FTC's bulging case files.

According to the FTC, “consumers may be spending billions of dollars a year on unproven, fraudulently marketed, often useless health-related products, devices and treatments.” Worthless weight-loss products alone have proliferated so wildly that in 2004 the FTC launched “Operation Big Fat Lie” to target them. As of October 2005, the commission said it had secured court orders requiring more than $188 million in consumer redress judgments against defendants. And since the FTC relies mostly on negotiated settlements, which are like plea bargains, that $188 million is most likely a fraction of the actual ill-gotten gains from weight-loss scams.

Deception Can Be Bad for Your Health

Deception is practically built into the business plans of some major corporations, and entire brands have been built on false advertising. Consider the long and checkered history of Listerine, for example. In 1923 the Lambert Pharmacal Company started marketing what had been a relatively ineffective hospital antiseptic as a mouthwash that could cure “halitosis,” a medical term not much used until Lambert's ads made it a household word. Sales of Listerine exploded, going from $100,000 a year in 1921 to more than $4 million in 1927 and $7 million in 1930. But the ads were false: no mouthwash can cure bad breath. Bad breath has a variety of causes, including certain foods, smoking, gum disease, dry mouth, diabetes, and even dieting, which can't be offset by any mouthwash. As the American Dental Association now emphasizes in bold print on its website: “Mouthwashes are generally cosmetic and do not have a long-lasting effect on bad breath.”

Other Listerine ads in the 1930s and 1940s claimed that the same product could cure “infectious dandruff” when rubbed on the scalp, a preposterous claim given that dandruff isn't caused by infection. For decades Listerine also claimed to cure sore throats and to reduce the likelihood of catching colds. As far back as 1931,

The Journal of the American Medical Association

railed against such false claims, saying “by its very name Listerine debases the fame of the great scientific investigator [Joseph Lister] who first established the idea of antisepsis.” And yet Listerine kept right on making its claims, decade after decade, stopping in 1977 only after it lost a five-year legal battle with the Federal Trade Commission that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a landmark case, the court upheld the commission's order to run a year's worth of corrective advertising, at a cost of $10.2 million, telling audiences that “Listerine will not prevent colds or sore throats or lessen their severity.”

And still the spin continues. Listerine ads still imply the product cures offensive breath odor by saying it “kills the germs that cause bad breath.” That's true but misleading. The germs come right back, as they always have. Lately, research has finally turned up a legitimate use for Listerine: it does slow the formation of dental plaque. But old habits die hard: Listerine (now owned by Pfizer) overstated its one virtue in a 2004 TV ad that claimed “Listerine's as effective as floss at fighting plaque and gingivitis. Clinical studies prove it.” But the clinical studies proved no such thing, because they failed to ensure that the subjects using floss were using it correctly. A leading maker of dental floss sued Pfizer, and Judge Denny Chin of the U.S. District Court of Manhattan ruled that Pfizer's studies “proved only that Listerine is âas effective as improperly-used floss.'” On January 6, 2005, he ordered the ads off the air. Chin also said the ads might be causing real physical harm: “I find that Pfizer's false and misleading advertising also poses a public health risk, as the advertisements present a danger of undermining the efforts of dental professionalsâ¦to convince consumers to floss on a daily basis.” We'll have more to say about Listerine later, showing you how its advertising displayed classic warning signs of deception.

In extreme cases, commercial deception can cost lives. In May 2004, the FTC sued a Canadian outfit called Seville Marketing, Ltd., accusing it of deceptively advertising something called Discreet, supposedly a home test for HIV. Seville claimed its product was 99.4 percent accurate, but the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 59.3 percent of tested kits provided inaccurate results. These included both false HIV-positive results and false HIV-negative results. Buyers of Discreet would have done better by flipping a coin to see if they were infected or not.

It wasn't until a year later, May 18, 2005, that Seville agreed to settle the case, with a court order prohibiting the company from selling its test kits or making deceptive claims. Seville also agreed to let the FTC tell its customers that the product didn't work as advertised and that they should contact a health professional. The FTC offered no estimate of how many HIV-infected persons might have been lulled into a false sense of security by an erroneous negative reading. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that many people delayed treatment or unknowingly spread the virus to others because they were deceived by Seville's advertising.