Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes - and Why (24 page)

Read Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes - and Why Online

Authors: Amanda Ripley

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Self Help, #Adult, #History

The last phase of the survival arc is the decisive moment. Given the right mix of conditions, catastrophes like a stampede can happen. Since 1990, more than 2,500 people have been killed in crowd crushes during the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Islam’s holy places in Saudi Arabia. This picture shows the normally peaceful crowd outside Mecca.

Credit: Khalil Hamra/AP

Saudi security officers and rescue workers gather by the dead bodies after a stampede in Mina on January 12, 2006. At least 346 people were killed, and nearly 1,000 were injured.

Credit: Muhammed Muheisen/AP

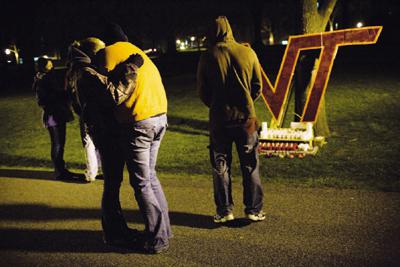

The most common reaction to a life-or-death situation is to do nothing. A kind of involuntary paralysis sets in, as experienced by a young man trapped in a classroom during the massacre at Virginia Tech in 2007. Here, students console each other at a campus vigil the night of the shootings.

Credit: Stephen Voss/WpN

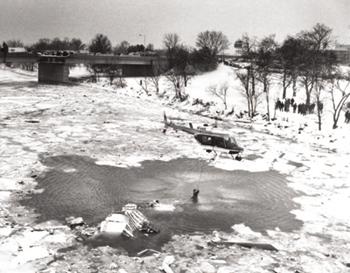

Sometimes people will take seemingly inexplicable risks to save total strangers. After Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the frozen Potomac River in Washington, DC, on January 13, 1982, dozens of people watched from the banks as the survivors clung to the wreckage. Eventually, three men jumped in to help, and a U.S. Park Police helicopter pulled the survivors to safety.

Credit: Charles Pereira/U.S. Park Police

What causes heroism? Roger Olian jumped into the freezing water the day of the Potomac River disaster because he had something to lose if he didn’t, he says. “If you didn’t get anything out of it, I mean flat-out nothing, you wouldn’t do it.” He is pictured here beside the Air Florida crash site, twenty-five years later.

Credit: Katie Ellsworth

Part ThreeEvery disaster holds evidence of the human capacity to do better. On 9/11, Rick Rescorla, head of security for Morgan Stanley and a decorated Vietnam veteran, sang songs into a bullhorn to keep people moving. He had spent years training the company’s 2,700 employees to get out fast in an emergency.

Credit: Eileen Maher Hillock

The Decisive Moment

6

Panic

A Stampede on Holy Ground

F

OR MORE THAN

fourteen hundred years, Muslims have journeyed to Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammad. The pilgrimage, or hajj, is required of every Muslim who can manage it. So the ritual has become one of the largest annual mass movements of human beings in history. People leave their homes with their life’s savings in their pockets, anxious about the adventure ahead, and they return with stories of finding peace in the most unlikely of places: in the middle of a scorched desert, deep inside an undulating crowd of strangers from all over the world.

But over the past two decades, something awful has happened to the hajj. In 1990, a stampede in a pedestrian tunnel killed 1,426 people in minutes. The list of dead included Egyptians, Indians, Pakistanis, Indonesians, Malaysians, Turks, and Saudis. Four years later, another stampede killed more than 270 pilgrims. After that, the tragedies began to follow a sickening rhythm, coming closer and closer together. In 1998, the count was at least 118. In 2001, at least 35 pilgrims were killed in a crush. In 2004, the body count rose to 251. In 2006, the crowd took more than 346 lives. All of the past five tragedies happened in the same area, called “jamarat,” around three pillars that all pilgrims must stone as a required ritual of the hajj. Somehow, a beautiful holy place became, for more than 2,500 people, a killing field.

What happened to the hajj? Why were people getting crushed and asphyxiated, year after year, when they had come to pray? What was causing what appeared to be mass panic?

Panic

is one of those words that change shape depending on the moment. Like

heroism,

it is defined in retrospect, often in ways that reflect more about the rest of us than about the facts on the ground. The word comes from mythology, which is appropriate. The Greek god Pan had a human torso and the legs, horns, and beard of goat. During the day, he roamed the forests and meadows, tending to flocks and playing songs on his flute. At night, he devoted much of his energy to the conquest of various nymphs. But from time to time, he amused himself by playing tricks on human travelers. As people passed through the lonely mountain slopes between the Greek city-states, Pan made those strange, creeping noises that slither from the darkness, never to be fully explained. He rustled the underbrush, and people quickened their pace; he did it again, and people ran for their lives. Fear at such harmless noises came to be known as “panic.”

Sometimes we use panic to mean a rippling kind of terror that robs us of self-control. But it can also be a reason for fear. There is panic, the emotion, and then there is panic, the behavior—the irrational shrieking and clamoring and shoving that can jeopardize the survival of ourselves and those around us. Both meanings get conflated in one short word, overloaded with implications. This chapter is about panic, the behavior, as manifested in a stampede—one of the most frightening and extreme versions of panic.

This chapter also marks the beginning of the end—the final phase of the survival arc. After denial and deliberation comes what I will call the decisive moment. This is a phrase borrowed from Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French photographer who may be the father of modern photojournalism. For him, the decisive moment was, among other things, “the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.” It happened when his camera managed to capture the essence of a thing or a person in a single frame.

Likewise, the last stage in the survival arc is over in a flash. It is the sudden distillation of everything that has come before, and it determines what, if anything, will come after. As in photography, what happens in this single moment depends on many things: timing, experience, sensibility—and, perhaps most of all, luck. What happens once we have accepted the fact that something terrible is upon us and deliberated our options? Panic is the worst-case scenario in the human imagination. All norms of behavior, all the things that make us human, dissolve, and all that remains is chaos. If we think back to the dread equation, panic scores high on every metric: uncontrollability, unfamiliarity, imaginability, suffering, scale of destruction, and unfairness. The only thing as dreadful as panic might be terrorism.

The current fashion in disaster research is to deny that panic ever happens. But one exaggeration doesn’t fix another exaggeration. Yes, people rarely do hysterical things that violate basic social mores. The vast majority of the time, as we have seen, panic does not occur. Doing nothing at all is in fact a much more common reaction to a disaster, as we’ll see in the next chapter. Afterward, people may say they “panicked,” and the media may report a “panic,” but in truth almost no one misbehaved. They felt their breath quicken and their heart pound. They felt afraid, in other words, and it was an uncomfortable sensation. But they didn’t actually become wilding maniacs, because to do so was not in their interest.

When you think about it, panic is not a very adaptive behavior. We probably could not have evolved to this point by doing it very often. But the enduring expectation that regular people

will

panic leads to all kinds of distrust on the part of neighbors, politicians, and police officers. The idea of panic, like the Greek god for which it is named, grips the imagination. The fear of panic may be more dangerous than panic itself.

But just because panic is rare doesn’t mean we shouldn’t speak of it. Panic does happen. This chapter is a cautious exploration of the exception: What is panic? When does it happen, and why? How can you make it stop?

A Woman Down

At the end of 2005, Ali Hussain, a driving instructor from Huddersfield, England, went on the hajj with his wife, Belquis Sadiq, a social worker for the elderly. The couple had been married for seventeen years and had four children, the youngest of whom was eight years old. Both Hussain and Sadiq had been on the pilgrimage before separately, and Islam requires only one hajj per lifetime. But they had always wanted to have the experience together. So on December 29, Hussain and his wife left for Saudi Arabia with an organized tour group of 135 other Muslims from their area.

On January 12, Hussain and Sadiq gathered their pebbles together and left their hotel for jamarat, the location of the previous four stampedes. Jamarat is a stretch of land surrounding three stone pillars, which are required stops on the hajj. In a ritual known as the “stoning of the devil,” pilgrims must pelt the pillars with pebbles three separate times. It is a cleansing ritual, meant to commemorate the way Abraham, in the Islamic version of the story, repelled Satan each time he tried to stop him from sacrificing his son Ishmael. In the 1970s, the Saudis built an overpass to allow two levels of pilgrims to participate in the stoning at once. As the crowds grew, jamarat became the most dangerous bottleneck in the world.