Voices from the Dark Years (29 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Because the German occupants are usually cast as villains in media depictions of the occupation, it is interesting that Krause found Otto von Stülpnagel an urbane and civilised soldier trying to fulfil an impossible task. As Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich, he was not only the ranking Wehrmacht general in France, but also responsible for ensuring that the troops under his command observed the provisions of international law, including the Hague Conventions, which for the most part they did, to begin with. The Waffen-SS was, of course, a parallel army, and not part of the Wehrmacht structure.

Krause found life on Von Stülpnagel’s staff rather genteel, indeed old-fashioned. Although known officially as

Stabshilferinnen

, most of the secretaries came from good families and were nicknamed

Edeltippsen

(‘noble typists’). To avoid illicit liaisons, they were strictly segregated, except during working hours, had separate sleeping accommodation and their own canteen. Refusing the posting to his HQ of any officer who could not speak good French, and discouraging contact with Abetz’s staff in the embassy and SS-Brigadeführer Karl Oberg’s SS in Avenue Lannes and Avenue Foch, Von Stülpnagel had a number of intellectuals on his staff and enjoyed discussing history or mathematics with them in his private dining room of the Hôtel Raphaël. He also encouraged junior officers to use permanently reserved boxes at the opera and the best theatres when no high-ranking visitors claimed them. On these occasions, they wore civilian clothes in order not to disturb the audience.

In his spare time, Krause used a Nansen passport to attend classes at the Sorbonne, which was forbidden for German personnel, and there continued his studies of Hebrew and Arabic, paying for his one-to-one lessons with food and clothing.

16

With fluent French, Krause found contacts with ordinary French people very relaxed but, in common with many other Wehrmacht officers, was wary of approaches by French collaborationists. His arrival in Paris was perfectly timed to witness the start of the PCF campaign to tie down tens of thousands of German personnel who could otherwise have been sent to Hitler’s newly opened Russian front. On 13 August communist activists Maurice Le Berre and Albert Manuel hacked to death a German soldier with a chopper and a bayonet near the Porte d’Orléans. Six days later a German firing squad executed two other men arrested during a PCF demonstration – Henri Gautherot and Szmul Tyszelman, an immigrant only naturalised in 1939 and known in party circles as ‘Titi’, who were accused of thefts of explosives.

On 21 August, during the morning rush hour at the Metro station Barbès-Rochechouart, a 22-year-old communist agitator and veteran of the Spanish Civil War who styled himself ‘Colonel Fabien’, assassinated a Kriegsmarine lieutenant in charge of a clothing store – allegedly to avenge the death of Titi. Pierre Georges, to use Fabien’s real name, may have been praised for this by fellow communists, but throughout the occupation until the Allied landings the population generally disapproved of acts of violence against German personnel, asking themselves what did killing one or 100 Germans achieve, except invite reprisals?

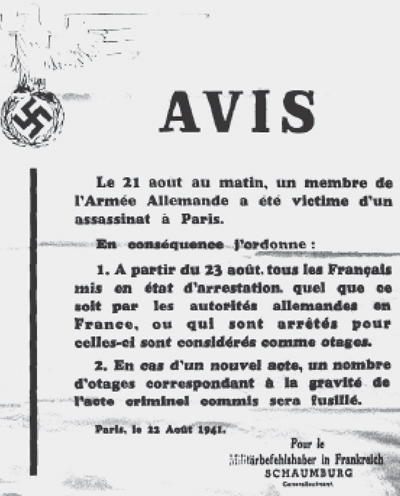

The hostage ordinance.

They were right. On the morning after the assassination, on every street corner Parisians perused a bilingual poster in German and French, in which Von Stülpnagel’s deputy Lieutenant-General Schaumburg promulgated the Hostage Ordinance.

With minor differences between the French and German texts, it reads:

On the morning of 21 August a member of the Wehrmacht was the victim of assassination in Paris. I therefore order as follows: 1. On and after 23 August any French person under arrest for whatever reason shall be considered a hostage; 2. On each future occasion a number of hostages corresponding to the gravity of the crime will be shot. [Signed by Lieutenant-General Schaumberg, Military Commander in France, Paris, 22 August 1941.]

Initially, forty-eight hostages were shot at Châteaubriant, Nantes and Paris. Stülpnagel realised the PCF campaign was concerted by Moscow to alienate the population from the occupying forces but, in the absence of convicted perpetrators, he could not fail to take reprisals without inviting his forces to take matters into their own hands – as frequently happens in such situations. Although many innocent people were randomly executed during the next three years in reprisals for sabotage and attacks on German personnel, a large number of those shot were in fact previously arrested communist activists. One compromise way out was to blame the Jewish community, which was fined 1 million francs

17

on the logic that the PCF activists ordering and executing the outrages were mainly Jewish immigrants like Tyszelman and illegals like Abraham Trzebucki, who was arrested while collecting money for an underground organisation, rapidly tried by one of Pucheu’s new courts and guillotined on 27 August.

That was a day of bloodshed, some of it unlamented. Pierre Laval and Marcel Déat were at the Borgnis-Desbordes barracks in Versailles reviewing the first contingent of the LVF in their new Wehrmacht uniforms with a distinguishing tricolour badge and

France

on their left arms, when a 21-year-old recruit in the parade pulled out his revolver and fired five shots at them. Although neither target was badly wounded, the initial outrage at the attack triggered a witch-hunt for the communists responsible. Colette was a far-right renegade and probably the hitman for Déat’s rival Deloncle, the body of whose secretary was found floating in the Seine, after she had been killed to stop her telling what she knew.

18

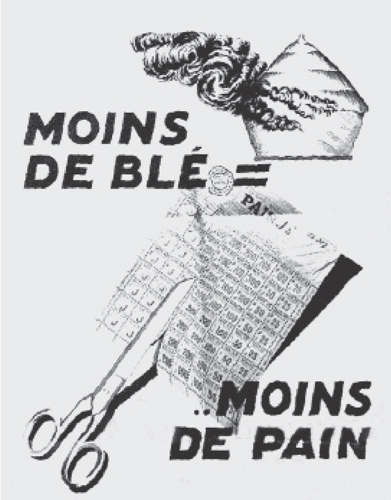

A poster warning that setting fire to crops would mean less bread for the French people.

When, in September, saboteurs set fire to haystacks and standing crops in the Occupied Zone, prefects of police blamed communist saboteurs. As a government poster made plain, less corn meant less bread on the family table. The mathematics were simple: since the Germans took their 20 per cent levy of the

total

crop, it was the French who suffered the shortfall.

In Moissac, Mayor Delthil had been one of the senators who voted to grant dictatorial powers to Pétain, and the prefect of Tarn-et-Garonne considered him to have handled his town’s problems wisely. Yet, old political enemies manoeuvred him out of office in January 1941 for ‘creating an island of resistance against the policies of the Marshal’ within the town hall

19

and when compromise candidate Dr Louis Moles replaced Delthil on 31 March.

Although the town council dutifully voted to change the name of

la rue des franc-maçons

to

la rue des Compagnons de France

nobody bothered to change the road signs. As the prefect dryly noted, ‘respect for the person of the head of state does not entail support for his policies of collaboration’.

20

More importantly, as far as local people were concerned, the potato harvest had been poor, and long queues at the butchers’ shops and groceries caused grumbling. All over France posters appealed to those fed up with waiting to be served to let war-wounded men, pregnant women and mothers of small children go to the head of the queue. Hungry people who had traditionally had full stomachs might be expected to blame their leaders, yet senior Vichy official Pierre Nicolle noted on a visit to Paris how Parisians seemed to have stopped thinking for themselves altogether, being interested only in where their next meal was coming from.

N

OTES

1.

Burrin,

Living with Defeat

, p. 377.

2.

Quoted by L. Chabrun et al.,

L’Express

, 10 October 2005.

3.

Diamond,

Women and the Second World War

, p. 23.

4.

La Vie à en mourir

, ed. V. Krivopissko (Paris: Tallandier, 2003), pp. 43–6.

5.

Chronique de la France

, p. 1,104.

6.

Webster, p. 141.

7.

Ibid., p. 143.

8.

Ibid., p. 140.

9.

Undated photocopy of cutting.

10.

Bédarida,

Les Catholiques dans la Guerre

, p. 139.

11.

Cahen-D’Anvers,

Baboushka Remembers

, pp. 210–12.

12.

Pryce-Jones,

Paris

, p. 117.

13.

La

Revue des Deux Mondes

, 15 September 1940.

14.

Pechanski,

Collaboration and Résistence

, p. 65.

15.

P. Pétain,

Discours aux Français

(Paris: Albin Michel, 1989), p. 172.

16.

Pryce-Jones,

Paris

, pp. 236–9.

17.

Ibid., p. 124.

18.

Ibid., p. 117.

19.

Boulet

,

‘Histoire de Moissac’, p. 115.

20.

Ibid., p. 118.

13

In France the Scout and Guide movement was divided by religion into Protestant, Catholic and Jewish organisations, all under the Vichy-approved umbrella of Les Scouts de France. With the backing of the Jewish scouting organisation Eclaireurs Israélites de France (EIF), an extraordinary Romanian Jewess who had come to France in 1933 to study medicine persuaded the town council to let her set up a reception centre for children at risk in the municipally owned Maison de Moissac.

1

From that humble start, Shatta Simon managed on a shoestring budget to save the lives of 865 children. One thing they all recalled in later life was her smile of welcome.