Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball's 101 All-Time Best Announcers (17 page)

Read Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball's 101 All-Time Best Announcers Online

Authors: Curt Smith

On October 2, 1963, Harwell called Sandy Koufax's Classic-high 15 Ks.

Five years later to the day he began another Series. "Gibson has tied the

record.... Trying for number 16 right now against Cash.... Swing and a

miss! He did it!" St. Louis took a 3-1 game lead. In Game Five, Ernie suggested blind folk-singer Jose Feliciano for the Anthem. He crashed NBC's

switchboard. "This was Viet Nam-people saw him, thought hippies with the guitar and dark glasses." The Cardinals scored three first-inning runs. Jose

should have sung a coda.

Detroit forced Game Seven. Scoreless inning shadowed inning. Cash and

Horton singled in the seventh. Jim Northrup lined to center. "Here comes

Flood," said Harwell. "He's digging hard. He almost fell down! It's over his

head for a hit!" Tigers: 4-1. Patient: baseball. Placebo: Detroit.

"`Sixty-eight," Ernie said as in a rosary. "People obsessed, wondering when

we'd win again [ 1972 A.L. East]." In the clubhouse, the Baptist shunned profanity. On the air, the teetotaler touted Stroh. On the road, he visited friends.

"You can read books listening to Ernie, or go smelt fishing listening to

him, or pick mushrooms in the woods with him in your ear," William Taaffe

wrote. In 1973, Henry Aaron passed homer 700. Harwell wrote "Move Over

Babe, Here Comes Henry" 55th of his more than 70 songs. "I'm drawn to

words [for Sammy Fain, Johnny Mercer, and B. J. Thomas, among others]. I

get an expression and work on rides from one city to another."

In 1976, a tyro expressed himself as no one had: "for one year," said

Ernie, "even bigger than McLain." On June 28, Mark Fidrych acknowledged

the first network TV sports curtain call. "They're not going to stop clapping

until the Bird comes from the dugout," said ABC's Warner Wolf. "Mark

Fidrych is born tonight on coast-to-coast television." "The Bird," after the

"Sesame Street"TV character, jammed stadia, addressed the ball, and manicured the mound.

Infielders Lou Whitaker and Alan Trammell became a more enduring

institution. Another could be heard saying, "That ball nabbed by a guy from

Alma, Michigan." Each day a different town snagged a foul. "Hey, Ernie, let a

guy from Hope [Holland, or Sarnia] grab one!" pled a bystander. As a boy I

recall thinking that he had a lot of friends.

Detroit did in 1984: only the fourth team to lead the league or division

each day. It swept the L.C.S., took a 3-1 game Series edge, and led next day,

5-4. Manager Sparky Anderson tried a ploy. "Five bucks you don't hit one

out," he yelled from the dugout. Steamed, Kirk Gibson signaled, doubling the

bet. "He swings, and there's a long drive to right!" said Harwell. "And it is a

home run for Gibson! ... The Tigers lead it, 8 to 4!"

By now Michigan would no more miss Ernie-"Mr. Kaline"; "lovely

Lulu"; "two for the price of one!"; "a big Tiger hello"; "lonnng gone" of a

dinger; "he played every hop perfectly except the last"-than burn the U.S.

flag. In 1990, ex-football coach Bo Schembechler became Tigers president: too arrogant to grasp his baseball ignorance, and too ignorant to grasp his

arrogance.

On December 19, Harwell said he would not return-"I'm fired"-after 1991. The Free Press screamed: "A Gentleman Wronged." A chant filled

Joe Louis Arena: "We Want Ernie!" T-shirts blared, "Say It Ain't So, Bo!" A

DetroitTV poll showed Harwell 9,352, Schembechler 265. Dishonor among

thieves: Bo and WJR Radio swapped blame. Their Grinch stealing Christmas

was mean, coarse, and dumb.

The '91ers closed at Baltimore. Our hero was feted in the Oval Office

and on Capitol Hill. "Someone said I was lucky. They pointed out usually you

have to die before people say nice things about you."Tony Hanley, 13, wrote

from Belding, Michigan: "If you need anything, a job, or money, or you need

a place to stay, or even a new organ, just call."

Next year Harwell called CBS Radio's "Game of the Week." Finer: ire at

his firing greased the franchise's sale. Mr. Tiger was rehired. Axed, Schembechler finally got the Importance of Being Ernie. "Mel and the Yankees,

Brooklyn and Barber, so many Voices canned," said Bob Costas. "Baseball is

clueless about how the announcer helps their team."

Pro: Detroit's booth rivaled pinball. "On a fall night, few people, outfielders

would hear you," said Harwell. Con: Tiger Stadium aged, closing September

27, 1999, its flag lowered and passed among 65 ex-Tigers in a chronological

line from the flagpole to the plate for transfer to Comerica Park. Ernie said

good-bye over the P.A. microphone, voice breaking, lights dimming.

"Farewell, old friend. We will remember."

His last broadcast year was 2002. Harwell opened the American Stock

Exchange. The Tigers unveiled a statue on Ernie Harwell Day. "The only

other day I remember was when the sheriff of Fulton County in Georgia gave

me a day to get out of town." Croquet was then the hipster sport, then the

NFL, then NBA. Baseball would survive: "an individual sport like Gary

Cooper in High Noon. A distinctly American sport"-and life.

In 1981, he invoked "a tongue-tied kid from Georgia, growing up to be an

announcer and praising the Lord for showing him the way to Cooperstown."

You thought of Ernie, as in Harwell; Tiger, as in baseball; class, as in friend.

He still made people happy.

ERNIE NARWELL

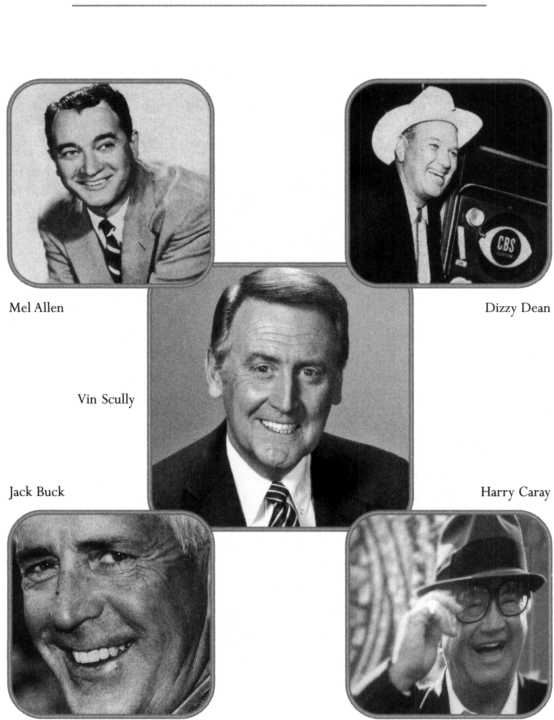

Walt Whitman wrote, "I hear America singing, the varied caroles I hear." Mel

Allen sang through eleven U.S. presidents, nine commissioners, and four

major wars. In 1939, he became Voice of the Yankees. He was fired in 1964

after 18 flags, 12 world titles, and nearly 4,000 games. Allen left the air,

knew private hell, then forged TV's brilliant "This Week In Baseball." He had

all, lost all, and, incredibly, came back.

At peak, Mel was sport's five-star mouthpiece-to Variety magazine,

"one of the 25 most recognizable voices in the world." It was deep, full, and

Southern, mixing Billy Graham and James Earl Jones. In Omaha, Allen once

hailed a cab. "Sheraton, please," he said, simply. The cabbie's head jerked like

a swivel. "The voice was astonishing," said 1953-56 Yankees colleague Jim

Woods. Ibid, debate about The Voice.

Depending on your view, Mel was a saladin, random chatterer, or surpassing personality of the big city in the flesh. Red Barber thought him prejudiced. The Mets' Lindsey Nelson was antipodal: "The best of all time to

broadcast the game." All conceded Mel's drop-dead lure.

Damn Yankees sang, "You've Gotta Have Heart." Born on Valentine's Day,

Mel fused "Dear Heart," "Heart of Gold," and "Heartbreak Hotel."

"Give me a child until he is seven," vowed Saint Francis of Assisi, "and you

may have him afterward." Melvin Israel was born in 1913 to Julius and Anna,

Russian emigrants who owned a clothing store in Johns, Alabama, 25 miles

from Birmingham. (In 1940, he dropped Israel and adopted his dad's middle

name. "The Yanks' idea," Mel said, wryly. "They told me it was more

generic.")

The child walked at nine months, spoke sentences at one year, read box

scores at five. "I'd go to our outside john," he said, "and devour a Montgomery

Ward catalogue." Allen graduated from grammar school at 11; high school,

15; the University of Alabama, 23. New York had the adult afterward. In

1936, he went there for a week's vacation. The trip lasted 60 years.

On a lark, Mel auditioned as a $45-a-week CBS Radio announcer. He

understudied Bob Trout and Ted Husing, interrupted Kate Smith to report

the Hindenburg crash, and introduced Perry Como on "The Pick and Pat Minstrels Show." Work at warp-speed: Kentucky Derby, International Polo

Games, and Vanderbilt Cup auto race. "The weather is awful and I'm in a

plane when the race is called off." Filling time, he ad-libbed for an hour.

"Allen [went] up there a raw kid from the turntable department," wrote

Ron Powers. "He came hack down a star." Often the ex-Piedmont League bat

boy drove from CBS to the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium, watched

players isolated in his attention, and broadcast sotto voce. "I sat and thought,

`I'd give anything to broadcast in a place like this.' " God answered through

soft soap, not hard sell.

In 1939, the Stripes and Jints debuted on radio. Arch McDonald had formerly done the Senators. One day an aide began an Ivory Soap ad by saying

"ovary." He laughed, repeated it, and was fired, replaced by Mel. Soon Arch

beat a path back to Washington. Within a year, so far, so fast, too fast, he often

said, for his own good, Allen had traded baseball's fringe for core the Voice

of the Yankees, at 26.

Mel knew what he had-"more history to call," said Nelson, "than any

sportscaster ever." Its stage was The Stadium's vast power alleys, pee-wee

lines, and triple tiers. The stars were idols: Phil Rizzuto (to Mel, "Scooter")

and Allie Reynolds ("SuperChief") and Lou Gehrig ("Iron Horse," a quiet

man, a hero). Said Bob Costas: "Not just baseball players, but personalities of

the time."

On July 4, 1939, the Bronx housed baseball's Gettysburg Address. Said

Gehrig: "I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth." Next

spring, dying of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, he visited the dugout, shuffled to

the bench, sat down, and patted Allen's knee. "I never got a chance to listen to

your games before because I was playing every day. But I want you to know

they're the only thing that keeps me going."As Gehrig left, Mel sobbed.

At that moment Allen seemed a Yankee to his pinstriped underwear.

Their sunny-dark star wore none. By 1947, racked by cancer, Babe Ruth

could barely talk. The trademark camel-hair coat and matching cap draped a

shell. Mel introduced him on his Day. "Babe, do you want to try and say

something?" he bayed above the crowd.

Ruth croaked, "I must."

Babe returned to the dugout. Mel returned to selling more cigars, cases of

beer, safety razors, and fans on baseball than any broadcaster who ever lived.

Allen's first World Series was 1938. Before the 1942 opener, he thought, "as

I always did, about one solitary fan-Ralph Edwards [from `This IsYour Life']

taught me this who I imagined sitting a few feet away. In my mind, he was

my audience. I was talking to him."