Voyage of the Beagle (35 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

The young cells at the end of the branches of these corallines contain quite immature polypi, yet the vulture-heads attached to them, though small, are in every respect perfect. When the polypus was removed by a needle from any of the cells, these organs did not appear in the least affected. When one of the vulture-like heads was cut off from the cell, the lower mandible retained its power of opening and closing. Perhaps the most singular part of their structure is, that when there were more than two rows of cells on a branch, the central cells were furnished with these appendages, of only one-fourth the size of the outside ones. Their movements varied according to the species; but in some I never saw the least motion; while others, with the lower mandible generally wide open, oscillated backwards and forwards at the rate of about five seconds each turn; others moved rapidly and by starts. When touched with a needle, the beak generally seized the point so firmly that the whole branch might be shaken.

These bodies have no relation whatever with the production of the eggs or gemmules, as they are formed before the young polypi appear in the cells at the end of the growing branches; as they move independently of the polypi, and do not appear to be in any way connected with them; and as they differ in size on the outer and inner rows of cells, I have little doubt that in their functions they are related rather to the horny axis of the branches than to the polypi in the cells. The fleshy appendage at the lower extremity of the sea-pen (described at Bahia Blanca) also forms part of the zoophyte, as a whole, in the same manner as the roots of a tree form part of the whole tree, and not of the individual leaf or flower-buds.

In another elegant little coralline (Crisia?) each cell was furnished with a long-toothed bristle, which had the power of moving quickly. Each of these bristles and each of the vulture-like heads generally moved quite independently of the others, but sometimes all on both sides of a branch, sometimes only those on one side, moved together coinstantaneously; sometimes each moved in regular order one after another. In these actions we

212

apparently behold as perfect a transmission of will in the zoophyte, though composed of thousands of distinct polypi, as in any single animal. The case, indeed, is not different from that of the sea-pens, which, when touched, drew themselves into the sand on the coast of Bahia Blanca. I will state one other instance of uniform action, though of a very different nature, in a zoophyte closely allied to Clytia, and therefore very simply organised. Having kept a large tuft of it in a basin of salt-water, when it was dark I found that as often as I rubbed any part of a branch, the whole became strongly phosphorescent with a green light: I do not think I ever saw any object more beautifully so. But the remarkable circumstance was, that the flashes of light always proceeded up the branches, from the base towards the extremities.

The examination of these compound animals was always very interesting to me. What can be more remarkable than to see a plant-like body producing an egg, capable of swimming about and of choosing a proper place to adhere to, which then sprouts into branches, each crowded with innumerable distinct animals, often of complicated organisations. The branches, moreover, as we have just seen, sometimes possess organs capable of movement and independent of the polypi. Surprising as this union of separate individuals in a common stock must always appear, every tree displays the same fact, for buds must be considered as individual plants. It is, however, natural to consider a polypus, furnished with a mouth, intestines, and other organs, as a distinct individual, whereas the individuality of a leaf-bud is not easily realised; so that the union of separate individuals in a common body is more striking in a coralline than in a tree. Our conception of a compound animal, where in some respects the individuality of each is not completed, may be aided, by reflecting on the production of two distinct creatures by bisecting a single one with a knife, or where Nature herself performs the task of bisection. We may consider the polypi in a zoophyte, or the buds in a tree, as cases where the division of the individual has not been completely effected. Certainly in the case of trees, and judging from analogy in that of corallines, the individuals propagated by buds seem more intimately related to each other, than eggs or seeds are to their parents. It seems now pretty well established that plants propagated by buds all

213

partake of a common duration of life; and it is familiar to every one, what singular and numerous peculiarities are transmitted with certainty, by buds, layers, and grafts, which by seminal propagation never or only casually reappear.

Tierra del Fuego, first arrival—Good Success Bay—An account of the Fuegians on board—Interview with the savages—Scenery of the forests—Cape Horn—Wigwam Cove—Miserable condition of the savages—Famines—Cannibals—Matricide—Religious feelings—Great gale—Beagle Channel—Ponsonby Sound—Build wigwams and settle the Fuegians—Bifurcation of the Beagle Channel—Glaciers—Return to the ship—Second visit in the ship to the settlement—Equality of condition amongst the natives.

December 17th, 1832.

—Having now finished with Patagonia and the Falkland Islands, I will describe our first arrival in Tierra del Fuego. A little after noon we doubled Cape St. Diego, and entered the famous Strait of Le Maire. We kept close to the Fuegian shore, but the outline of the rugged, inhospitable Staten-land was visible amidst the clouds. In the afternoon we anchored in the Bay of Good Success. While entering we were saluted in a manner becoming the inhabitants of this savage land. A group of Fuegians partly concealed by the entangled forest, were perched on a wild point overhanging the

215

sea; and as we passed by, they sprang up and waving their tattered cloaks sent forth a loud and sonorous shout. The savages followed the ship, and just before dark we saw their fire, and again heard their wild cry. The harbour consists of a fine piece of water half surrounded by low rounded mountains of clay-slate, which are covered to the water's edge by one dense gloomy forest. A single glance at the landscape was sufficient to show me how widely different it was from anything I had ever beheld. At night it blew a gale of wind, and heavy squalls from the mountains swept past us. It would have been a bad time out at sea, and we, as well as others, may call this Good Success Bay.

In the morning the Captain sent a party to communicate with the Fuegians. When we came within hail, one of the four natives who were present advanced to receive us, and began to shout most vehemently, wishing to direct us where to land. When we were on shore the party looked rather alarmed, but continued talking and making gestures with great rapidity. It was without exception the most curious and interesting spectacle I ever beheld: I could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilised man: it is greater than between a wild and domesticated animal, inasmuch as in man there is a greater power of improvement. The chief spokesman was old, and appeared to be the head of the family; the three others were powerful young men, about six feet high. The women and children had been sent away. These Fuegians are a very different race from the stunted, miserable wretches farther westward; and they seem closely allied to the famous Patagonians of the Strait of Magellan. Their only garment consists of a mantle made of guanaco skin, with the wool outside: this they wear just thrown over their shoulders, leaving their persons as often exposed as covered. Their skin is of a dirty coppery-red colour.

The old man had a fillet of white feathers tied round his head, which partly confined his black, coarse, and entangled hair. His face was crossed by two broad transverse bars; one, painted bright red, reached from ear to ear and included the upper lip; the other, white like chalk, extended above and parallel to the first, so that even his eyelids were thus coloured. The other two men were ornamented by streaks of black powder, made of

216

charcoal. The party altogether closely resembled the devils which come on the stage in plays like Der Freischutz.

Their very attitudes were abject, and the expression of their countenances distrustful, surprised, and startled. After we had presented them with some scarlet cloth, which they immediately tied round their necks, they became good friends. This was shown by the old man patting our breasts, and making a chuckling kind of noise, as people do when feeding chickens. I walked with the old man, and this demonstration of friendship was repeated several times; it was concluded by three hard slaps, which were given me on the breast and back at the same time. He then bared his bosom for me to return the compliment, which being done, he seemed highly pleased. The language of these people, according to our notions, scarcely deserves to be called articulate. Captain Cook has compared it to a man clearing his throat, but certainly no European ever cleared his throat with so many hoarse, guttural, and clicking sounds.

They are excellent mimics: as often as we coughed or yawned, or made any odd motion, they immediately imitated us. Some of our party began to squint and look awry; but one of the young Fuegians (whose whole face was painted black, excepting a white band across his eyes) succeeded in making far more hideous grimaces. They could repeat with perfect correctness each word in any sentence we addressed them, and they remembered such words for some time. Yet we Europeans all know how difficult it is to distinguish apart the sounds in a foreign language. Which of us, for instance, could follow an American Indian through a sentence of more than three words? All savages appear to possess, to an uncommon degree, this power of mimicry. I was told, almost in the same words, of the same ludicrous habit among the Caffres; the Australians, likewise, have long been notorious for being able to imitate and describe the gait of any man, so that he may be recognised. How can this faculty be explained? is it a consequence of the more practised habits of perception and keener senses, common to all men in a savage state, as compared with those long civilised?

When a song was struck up by our party, I thought the Fuegians would have fallen down with astonishment. With equal surprise they viewed our dancing; but one of the young men, when asked, had no objection to a little waltzing. Little

217

accustomed to Europeans as they appeared to be, yet they knew and dreaded our firearms; nothing would tempt them to take a gun in their hands. They begged for knives, calling them by the Spanish word "cuchilla." They explained also what they wanted, by acting as if they had a piece of blubber in their mouth, and then pretending to cut instead of tear it.

I have not as yet noticed the Fuegians whom we had on board. During the former voyage of the

Adventure

and

Beagle

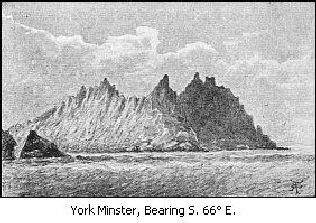

in 1826 to 1830, Captain Fitz Roy seized on a party of natives, as hostages for the loss of a boat, which had been stolen, to the great jeopardy of a party employed on the survey; and some of these natives, as well as a child whom he bought for a pearl-button, he took with him to England, determining to educate them and instruct them in religion at his own expense. To settle these natives in their own country was one chief inducement to Captain Fitz Roy to undertake our present voyage; and before the Admiralty had resolved to send out this expedition, Captain Fitz Roy had generously chartered a vessel, and would himself have taken them back. The natives were accompanied by a missionary, R. Matthews; of whom and of the natives, Captain Fitz Roy has published a full and excellent account. Two men, one of whom died in England of the smallpox, a boy and a little girl, were originally taken; and we had now on board, York Minster, Jemmy Button (whose name expresses his purchase-money), and Fuegia Basket. York Minster was a full-grown, short, thick, powerful man: his disposition was reserved, taciturn, morose, and when excited violently passionate; his affections were very strong towards a few friends on board; his intellect good. Jemmy Button was a universal favourite, but likewise passionate; the expression of his face at once showed his nice disposition. He was merry and often laughed, and was remarkably sympathetic with any one in pain: when the water was rough, I was often a little sea-sick, and he used to come to me and say in a plaintive voice, "Poor, poor fellow!" but the notion, after his aquatic life, of a man being sea-sick, was too ludicrous, and he was generally obliged to turn on one side to hide a smile or laugh, and then he would repeat his "Poor, poor fellow!" He was of a patriotic disposition; and he liked to praise his own tribe and country, in which he truly said there were "plenty of trees," and he abused all the other tribes: he stoutly declared that there

218

was no Devil in his land. Jemmy was short, thick, and fat, but vain of his personal appearance; he used always to wear gloves, his hair was neatly cut, and he was distressed if his well-polished shoes were dirtied. He was fond of admiring himself in a looking glass; and a merry-faced little Indian boy from the Rio Negro, whom we had for some months on board, soon perceived this, and used to mock him: Jemmy, who was always rather jealous of the attention paid to this little boy, did not at all like this, and used to say, with rather a contemptuous twist of his head, "Too much skylark." It seems yet wonderful to me, when I think over all his many good qualities, that he should have been of the same race, and doubtless partaken of the same character, with the miserable, degraded savages whom we first met here. Lastly, Fuegia Basket was a nice, modest, reserved young girl, with a rather pleasing but sometimes sullen expression, and very quick in learning anything, especially languages. This she showed in picking up some Portuguese and Spanish, when left on shore for only a short time at Rio de Janeiro and Monte Video, and in her knowledge of English. York Minster was very jealous of any attention paid to her; for it was clear he determined to marry her as soon as they were settled on shore.