Voyage of the Beagle (80 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

We come now to our third class of Fringing-reefs, which will require a very short notice. Where the land slopes abruptly under water, these reefs are only a few yards in width, forming a mere ribbon or fringe round the shores: where the land slopes gently under the water the reef extends farther, sometimes even as much as a mile from the land; but in such cases the soundings outside the reef always show that the submarine prolongation of the land is gently inclined. In fact the reefs extend only to that distance from the shore at which a foundation within the requisite depth from 20 to 30 fathoms is found. As far as the actual reef is concerned, there is no essential difference between it and that forming a barrier or an atoll: it is, however, generally of less width, and consequently few islets have been formed on it. From the corals growing more vigorously on the outside, and from the noxious effect of the sediment washed inwards, the outer edge of the reef is the highest part, and between it and the land

501

there is generally a shallow sandy channel a few feet in depth. Where banks of sediment have accumulated near to the surface, as in parts of the West Indies, they sometimes become fringed with corals, and hence in some degree resemble lagoon-islands or atolls, in the same manner as fringing-reefs, surrounding gently sloping islands, in some degree resemble barrier-reefs.

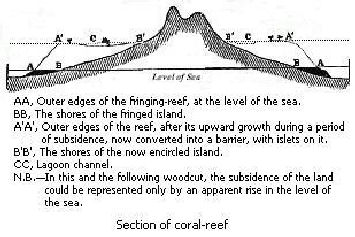

No theory on the formation of coral-reefs can be considered satisfactory which does not include the three great classes. We have seen that we are driven to believe in the subsidence of those vast areas, interspersed with low islands, of which not one rises above the height to which the wind and waves can throw up matter, and yet are constructed by animals requiring a foundation, and that foundation to lie at no great depth. Let us then take an island surrounded by fringing-reefs, which offer no difficulty in their structure; and let this island with its reef, represented by the unbroken lines in Plate 96, slowly subside. Now as the island sinks down, either a few feet at a time or quite insensibly, we may safely infer, from what is known of the conditions favourable to the growth of coral, that the living masses, bathed by the surf on the margin of the reef, will soon regain the surface. The water, however, will encroach little by little on the shore, the island becoming lower and smaller, and the space between the inner edge of the reef and the beach proportionally broader. A section of the reef and island in this state, after a subsidence of several hundred feet, is given by the dotted lines. Coral islets are supposed to have been formed on the reef; and a ship is anchored in the lagoon-channel.

502

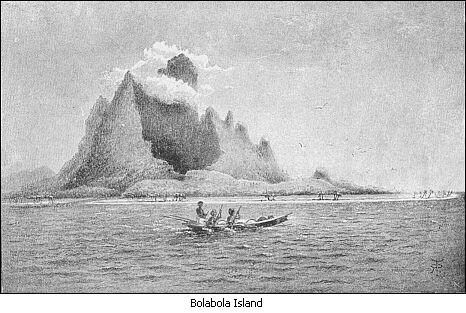

This channel will be more or less deep, according to the rate of subsidence, to the amount of sediment accumulated in it, and to the growth of the delicately branched corals which can live there. The section in this state resembles in every respect one drawn through an encircled island: in fact, it is a real section (on the scale of .517 of an inch to a mile) through Bolabola in the Pacific. We can now at once see why encircling barrier-reefs stand so far from the shores which they front. We can also perceive that a line drawn perpendicularly down from the outer edge of the new reef, to the foundation of solid rock beneath the old fringing-reef, will exceed by as many feet as there have been feet of subsidence, that small limit of depth at which the effective corals can live:—the little architects having built up their great wall-like mass, as the whole sank down, upon a basis formed of other corals and their consolidated fragments. Thus the difficulty on this head, which appeared so great, disappears.

If, instead of an island, we had taken the shore of a continent fringed with reefs, and had imagined it to have subsided, a great straight barrier, like that of Australia or New Caledonia, separated from the land by a wide and deep channel, would evidently have been the result.

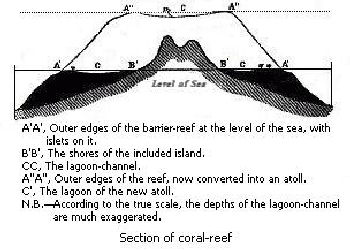

Let us take our new encircling barrier-reef, of which the section is now represented by unbroken lines, and which, as I have said, is a real section through Bolabola, and let it go on subsiding. As the barrier-reef slowly sinks down, the corals

503

will go on vigorously growing upwards; but as the island sinks, the water will gain inch by inch on the shore—the separate mountains first forming separate islands within one great reef—and finally, the last and highest pinnacle disappearing. The instant this takes place, a perfect atoll is formed: I have said, remove the high land from within an encircling barrier-reef, and an atoll is left, and the land has been removed. We can now perceive how it comes that atolls, having sprung from encircling barrier-reefs, resemble them in general size, form, in the manner in which they are grouped together, and in their arrangement in single or double lines; for they may be called rude outline charts of the sunken islands over which they stand. We can further see how it arises that the atolls in the Pacific and Indian Oceans extend in lines parallel to the generally prevailing strike of the high islands and great coast-lines of those oceans. I venture, therefore, to affirm that on the theory of the upward growth of the corals during the sinking of the land,

1

all the leading features in those wonderful structures, the lagoon-islands or atolls, which have so long excited the attention of voyagers, as well as in the no less wonderful barrier-reefs, whether encircling small islands or stretching for hundreds of miles along the shores of a continent, are simply explained.

1. It has been highly satisfactory to me to find the following passage in a pamphlet by Mr. Couthouy, one of the naturalists in the great Antarctic Expedition of the United States:—"Having personally examined a large number of coral-islands, and resided eight months among the volcanic class having shore and partially encircling reefs, I may be permitted to state that my own observations have impressed a conviction of the correctness of the theory of Mr. Darwin." The naturalists, however, of this expedition differ with me on some points respecting coral formations.

It may be asked whether I can offer any direct evidence of the subsidence of barrier-reefs or atolls; but it must be borne in mind how difficult it must ever be to detect a movement, the tendency of which is to hide under water the part affected. Nevertheless, at Keeling atoll I observed on all sides of the lagoon old cocoa-nut trees undermined and falling; and in one place the foundation-posts of a shed, which the inhabitants asserted had stood seven years before just above high-water mark, but now was daily washed by every tide; on inquiry I found that three earthquakes, one of them severe, had been felt here during the last ten years. At Vanikoro

504

the lagoon-channel is remarkably deep, scarcely any alluvial soil has accumulated at the foot of the lofty included mountains, and remarkably few islets have been formed by the heaping of fragments and sand on the wall-like barrier reef; these facts, and some analogous ones, led me to believe that this island must lately have subsided and the reef grown upwards: here again earthquakes are frequent and very severe. In the Society Archipelago, on the other hand, where the lagoon-channels are almost choked up, where much low alluvial land has accumulated, and where in some cases long islets have been formed on the barrier-reefs—facts all showing that the islands have not very lately subsided—only feeble shocks are most rarely felt. In these coral formations, where the land and water seem struggling for mastery, it must be ever difficult to decide between the effects of a change in the set of the tides and of a slight subsidence: that many of these reefs and atolls are subject to changes of some kind is certain; on some atolls the islets appear to have increased greatly within a late period; on others they have been partially or wholly washed away. The inhabitants of parts of the Maldiva Archipelago know the date of the first formation of some islets; in other parts the corals are now flourishing on water-washed reefs, where holes made for graves attest the former existence of inhabited land. It is difficult to believe in frequent changes in the tidal currents of an open ocean; whereas we have in the earthquakes recorded by the natives on some atolls, and in the great fissures observed on other atolls, plain evidence of changes and disturbances in progress in the subterranean regions.

It is evident, on our theory, that coasts merely fringed by reefs cannot have subsided to any perceptible amount; and therefore they must, since the growth of their corals, either have remained stationary or have been upheaved. Now it is remarkable how generally it can be shown, by the presence of upraised organic remains, that the fringed islands have been elevated: and so far, this is indirect evidence in favour of our theory. I was particularly struck with this fact, when I found, to my surprise,

505

that the descriptions given by MM. Quoy and Gaimard were applicable, not to reefs in general as implied by them, but only to those of the fringing class; my surprise, however, ceased when I afterwards found that, by a strange chance, all the several islands visited by these eminent naturalists could be shown by their own statements to have been elevated within a recent geological era.

Not only the grand features in the structure of barrier-reefs and of atolls, and of their likeness to each other in form, size, and other characters, are explained on the theory of subsidence—which theory we are independently forced to admit in the very areas in question, from the necessity of finding bases for the corals within the requisite depth—but many details in structure and exceptional cases can thus also be simply explained. I will give only a few instances. In barrier-reefs it has long been remarked with surprise that the passages through the reef exactly face valleys in the included land, even in cases where the reef is separated from the land by a lagoon-channel so wide and so much deeper than the actual passage itself, that it seems hardly possible that the very small quantity of water or sediment brought down could injure the corals on the reef. Now, every reef of the fringing class is breached by a narrow gateway in front of the smallest rivulet, even if dry during the greater part of the year, for the mud, sand, or gravel occasionally washed down kills the corals on which it is deposited. Consequently, when an island thus fringed subsides, though most of the narrow gateways will probably become closed by the outward and upward growth of the corals, yet any that are not closed (and some must always be kept open by the sediment and impure water flowing out of the lagoon-channel) will still continue to front exactly the upper parts of those valleys at the mouths of which the original basal fringing-reef was breached.