Voyage of the Beagle (82 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

I spent the greater part of the next day in walking about the town and visiting different people. The town is of considerable size, and is said to contain 20,000 inhabitants; the streets are very clean and regular. Although the island has been so many years under the English government, the general character of the place is quite French: Englishmen speak to their servants in French, and the shops are all French; indeed I should think that Calais or Boulogne was much more Anglified. There is a very pretty little theatre in which operas are excellently performed. We were also surprised at seeing large booksellers' shops, with well-stored shelves;—music and reading bespeak our approach to the old world of civilisation; for in truth both Australia and America are new worlds.

The various races of men walking in the streets afford the most interesting spectacle in Port Louis. Convicts from India are banished here for life; at present there are about 800, and they are employed in various public works. Before seeing these people, I had no idea that the inhabitants of India were such noble-looking figures. Their skin is extremely dark, and many of the older men had large mustaches and beards of a snow-white colour; this, together with the fire of their expression, gave them quite an imposing aspect. The greater number had been banished for murder and the worst crimes; others for causes which can scarcely be considered as moral faults, such as for not obeying, from superstitious motives, the English laws. These men are generally quiet and well-conducted; from their outward conduct, their cleanliness and faithful observance of their strange religious rites, it was impossible to look at them with the same eyes as on our wretched convicts in New South Wales.

May 1st.

—Sunday. I took a quiet walk along the sea-coast to the north of the town. The plain in this part is quite uncultivated; it consists of a field of black lava, smoothed over with coarse grass and bushes, the latter being chiefly Mimosas.

514

The scenery may be described as intermediate in character between that of the Galapagos and of Tahiti; but this will convey a definite idea to very few persons. It is a very pleasant country, but it has not the charms of Tahiti, or the grandeur of Brazil. The next day I ascended La Pouce, a mountain so called from a thumb-like projection, which rises close behind the town to a height of 2,600 feet. The centre of the island consists of a great platform, surrounded by old broken basaltic mountains, with their strata dipping seawards. The central platform, formed of comparatively recent streams of lava, is of an oval shape, thirteen geographical miles across in the line of its shorter axis. The exterior bounding mountains come into that class of structures called Craters of Elevation, which are supposed to have been formed not like ordinary craters, but by a great and sudden upheaval. There appear to me to be insuperable objections to this view: on the other hand, I can hardly believe, in this and in some other cases, that these marginal crateriform mountains are merely the basal remnants of immense volcanos, of which the summits either have been blown off or swallowed up in subterranean abysses.

From our elevated position we enjoyed an excellent view over the island. The country on this side appears pretty well cultivated, being divided into fields and studded with farm-houses. I was however assured that of the whole land not more than half is yet in a productive state; if such be the case, considering the present large export of sugar, this island, at some future period when thickly peopled, will be of great value. Since England has taken possession of it, a period of only twenty-five years, the export of sugar is said to have increased seventy-five fold. One great cause of its prosperity is the excellent state of the roads. In the neighbouring Isle of Bourbon, which remains under the French government, the roads are still in the same miserable state as they were here only a few years ago. Although the French residents must have largely profited by the increased prosperity of their island, yet the English government is far from popular.

3rd.

—In the evening Captain Lloyd, the Surveyor-general, so well known from his examination of the Isthmus of Panama, invited Mr. Stokes and myself to his country-house, which is situated on the edge of Wilheim Plains, and about six miles

515

from the Port. We stayed at this delightful place two days; standing nearly 800 feet above the sea, the air was cool and fresh, and on every side there were delightful walks. Close by a grand ravine has been worn to a depth of about 500 feet through the slightly inclined streams of lava, which have flowed from the central platform.

5th.

—Captain Lloyd took us to the Rivière Noire, which is several miles to the southward, that I might examine some rocks of elevated coral. We passed through pleasant gardens, and fine fields of sugar-cane growing amidst huge blocks of lava. The roads were bordered by hedges of Mimosa, and near many of the houses there were avenues of the mango. Some of the views where the peaked hills and the cultivated farms were seen together, were exceedingly picturesque; and we were constantly tempted to exclaim "How pleasant it would be to pass one's life in such quiet abodes!" Captain Lloyd possessed an elephant, and he sent it half-way with us, that we might enjoy a ride in true Indian fashion. The circumstance which surprised me most was its quite noiseless step. This elephant is the only one at present on the island; but it is said others will be sent for.

May 9th.

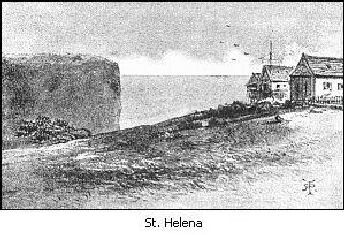

—We sailed from Port Louis, and, calling at the Cape of Good Hope, on the 8th of July we arrived off St. Helena. This island, the forbidding aspect of which has been so often described, rises abruptly like a huge black castle from the ocean. Near the town, as if to complete nature's defence, small forts and guns fill up every gap in the rugged rocks. The town runs up a flat and narrow valley; the houses look respectable, and are interspersed with a very few green trees. When approaching the anchorage there was one striking view: an irregular castle perched on the summit of a lofty hill, and surrounded by a few scattered fir-trees, boldly projected against the sky.

The next day I obtained lodgings within a stone's throw of Napoleon's tomb;

1

it was a capital central situation, whence I

516

could make excursions in every direction. During the four days I stayed here I wandered over the island from morning to night and examined its geological history. My lodgings were situated at a height of about 2000 feet; here the weather was cold and boisterous, with constant showers of rain; and every now and then the whole scene was veiled in thick clouds.

1. After the volumes of eloquence which have poured forth on this subject, it is dangerous even to mention the tomb. A modern traveller, in twelve lines, burdens the poor little island with the following titles,—it is a grave, tomb, pyramid, cemetery, sepulchre, catacomb, sarcophagus, minaret, and mausoleum!

Near the coast the rough lava is quite bare: in the central and higher parts feldspathic rocks by their decomposition have produced a clayey soil, which, where not covered by vegetation, is stained in broad bands of many bright colours. At this season the land, moistened by constant showers, produces a singularly bright green pasture, which lower and lower down gradually fades away and at last disappears. In latitude 16 degrees, and at the trifling elevation of 1500 feet, it is surprising to behold a vegetation possessing a character decidedly British. The hills are crowned with irregular plantations of Scotch firs; and the sloping banks are thickly scattered over with thickets of gorse, covered with its bright yellow flowers. Weeping-willows are common on the banks of the rivulets, and the hedges are made of the blackberry, producing its well-known fruit. When we consider that the number of plants now found on the island is 746, and that out of these fifty-two alone are

517

indigenous species, the rest having been imported, and most of them from England, we see the reason of the British character of the vegetation. Many of these English plants appear to flourish better than in their native country; some also from the opposite quarter of Australia succeed remarkably well. The many imported species must have destroyed some of the native kinds; and it is only on the highest and steepest ridges that the indigenous Flora is now predominant.

The English, or rather Welsh character of the scenery, is kept up by the numerous cottages and small white houses; some buried at the bottom of the deepest valleys, and others mounted on the crests of the lofty hills. Some of the views are striking, for instance that from near Sir W. Doveton's house, where the bold peak called Lot is seen over a dark wood of firs, the whole being backed by the red water-worn mountains of the southern coast. On viewing the island from an eminence, the first circumstance which strikes one is the number of the roads and forts: the labour bestowed on the public works, if one forgets its character as a prison, seems out of all proportion to its extent or value. There is so little level or useful land that it seems surprising how so many people, about 5000, can subsist here. The lower orders, or the emancipated slaves, are, I believe, extremely poor: they complain of the want of work. From the reduction in the number of public servants, owing to the island having been given up by the East India Company, and the consequent emigration of many of the richer people, the poverty probably will increase. The chief food of the working class is rice with a little salt meat; as neither of these articles are the products of the island, but must be purchased with money, the low wages tell heavily on the poor people. Now that the people are blessed with freedom, a right which I believe they value fully, it seems probable that their numbers will quickly increase: if so, what is to become of the little state of St. Helena?

My guide was an elderly man who had been a goatherd when a boy, and knew every step amongst the rocks. He was of a race many times crossed, and although with a dusky skin, he had not the disagreeable expression of a mulatto. He was a very civil, quiet old man, and such appears the character of the greater number of the lower classes. It was strange to

518

my ears to hear a man, nearly white and respectably dressed, talking with indifference of the times when he was a slave. With my companion, who carried our dinners and a horn of water, which is quite necessary, as all the water in the lower valleys is saline, I every day took long walks.

Beneath the upper and central green circle, the wild valleys are quite desolate and untenanted. Here, to the geologist, there were scenes of high interest, showing successive changes and complicated disturbances. According to my views, St. Helena has existed as an island from a very remote epoch: some obscure proofs, however, of the elevation of the land are still extant. I believe that the central and highest peaks form parts of the rim of a great crater, the southern half of which has been entirely removed by the waves of the sea: there is, moreover, an external wall of black basaltic rocks, like the coast-mountains of Mauritius, which are older than the central volcanic streams. On the higher parts of the island considerable numbers of a shell, long thought to be a marine species, occur imbedded in the soil. It proves to be a Cochlogena, or land-shell of a very peculiar form;

1

with it I found six other kinds; and in another spot an eighth species. It is remarkable that none of them are now found living. Their extinction has probably been caused by the entire destruction of the woods, and the consequent loss of food and shelter, which occurred during the early part of the last century.

1. It deserves notice that all the many specimens of this shell found by me in one spot differ as a marked variety from another set of specimens procured from a different spot.

2. Beatson's

St. Helena

. Introductory chapter, p. 4.

The history of the changes which the elevated plains of Longwood and Deadwood have undergone, as given in General Beatson's account of the island, is extremely curious. Both plains, it is said, in former times were covered with wood, and were therefore called the Great Wood. So late as the year 1716 there were many trees, but in 1724 the old trees had mostly fallen; and as goats and hogs had been suffered to range about, all the young trees had been killed. It appears also from the official records that the trees were unexpectedly, some years afterwards, succeeded by a wire grass which spread over the whole surface.

1

General Beatson adds that now this

519

plain "is covered with fine sward, and is become the finest piece of pasture on the island." The extent of surface, probably covered by wood at a former period, is estimated at no less than two thousand acres; at the present day scarcely a single tree can be found there. It is also said that in 1709 there were quantities of dead trees in Sandy Bay; this place is now so utterly desert that nothing but so well attested an account could have made me believe that they could ever have grown there. The fact that the goats and hogs destroyed all the young trees as they sprang up, and that in the course of time the old ones, which were safe from their attacks, perished from age, seems clearly made out. Goats were introduced in the year 1502; eighty-six years afterwards, in the time of Cavendish, it is known that they were exceedingly numerous. More than a century afterwards, in 1731, when the evil was complete and irretrievable, an order was issued that all stray animals should be destroyed. It is very interesting thus to find that the arrival of animals at St. Helena in 1501 did not change the whole aspect of the island, until a period of two hundred and twenty years had elapsed: for the goats were introduced in 1502, and in 1724 it is said "the old trees had mostly fallen." There can be little doubt that this great change in the vegetation affected not only the land-shells, causing eight species to become extinct, but likewise a multitude of insects.