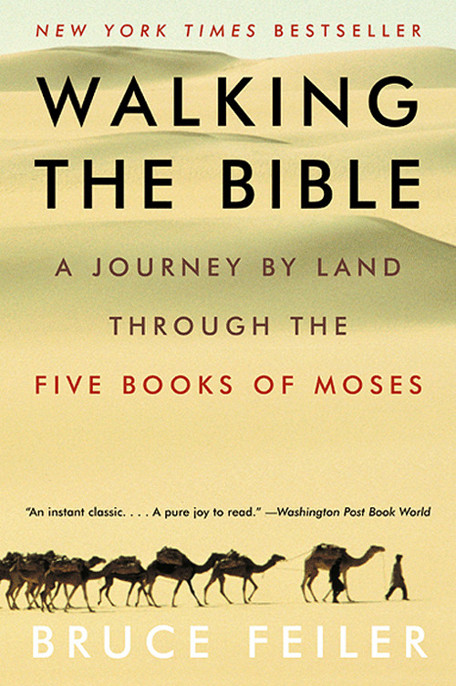

Walking the Bible

Authors: Bruce Feiler

BRUCE FEILER

F

OR MY SISTER

May your descendants

be as numerous as the stars

Now the Lord said to Abram,

“Go forth from your native land

and from your father’s house to the

land that I will show you.”

G

ENESIS

12:1

Contents

2. And They Made Their Lives Bitter

T

HE

G

REAT AND

T

ERRIBLE

W

ILDERNESS

1. A Land of Fiery Snakes and Scorpions

2. And the Earth Opened Its Mouth

3. Sunrise in the Palm of the Lord

A Study and Reading Group Guide to

Walking the Bible

T

he call to prayer sounded just after 3

P.M.

It came from a minaret, echoed off the storefronts, and stopped me, briefly, in the middle of the street. All around, people halted their hurrying and turned their attention, momentarily, to God. A few old men pulled cloaks around their shoulders and slipped into the back of a shop. Two boys rushed across the road and disappeared behind a stone wall. A woman picked up her basket of radishes and tiptoed out of sight. Part of me felt odd to be starting a journey into the roots of the Bible in a place so spiritually removed from my own. But continuing toward the center of town, I realized my unease might be a reminder of a truth tucked away in the early verses of Genesis: Abraham was not originally the man he became. He was not an Israelite, he was not a Jew. He was not even a believer in God—at least initially. He was a traveler, called by some voice not entirely clear that said: Go, head to this land, walk along this route, and trust what you will find.

Within minutes, the afternoon prayers were complete and people returned to the streets. Dogubayazit, in extreme eastern Turkey, was thuddingly bleak, with two asphalt roads intersecting in a neglected town of thirty thousand. Just outside of town, hundreds of empty oil tankers were parked in a double-file line waiting to cross the border into Iran. The trucks, the town, as well as most of the surrounding countryside, were completely overshadowed by a looming triangular peak with a pristine cap of snow.

Mount Ararat is a perfect volcanic pyramid 16,984 feet high, with a junior volcano, Little Ararat, attached to its hip. The highest peak in the Middle East (and the second highest in Europe), Big Ararat is holy to everyone around it. The Turks call it Agri Dagi, the Mountain of Pain. The Kurds call it the Mountain of Fire. Armenians also worship the mountain, which was in their homeland until a brutal war in 1915. I later met an Armenian in Jerusalem who took me into his home, where he had at least 150 representations of the mountain, including rugs, cups, coats of arms, bottles of cognac, and stained-glass windows. Mount Ararat is the first thing he thinks of every morning, he said, and the first thing his children drew when they were young.

I had come for a different reason. Genesis, chapter 8, says that Noah’s ark, after seven months on the floodwaters, came to rest on “the mountains of Ararat.” Mount Ararat is the first place mentioned in the Bible that can be located with any degree of certainty, and it seemed like a fitting place to begin my effort to reacquaint myself with the biblical stories by retracing the first five books through the desert. The topography of this part of Turkey, which includes the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates, permeates the early chapters of Genesis. Chaos, Creation, Eden, and Eve are all drawn from the fertile union of Mesopotamia, “the land between the rivers” and the birthplace of the Bible.

In recent years, however, this region has been one of the most volatile—and bloody—in the Middle East. Over forty thousand people have died in a largely overlooked war in which indigenous Kurds have tried to gain autonomy from Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. In every travel book I read about the region the author was at least briefly detained. The

Rough Guide

I brought actually superimposed a blank area over the region, saying it was too unsafe for its correspondent. “In our opinion, travel is emphatically not recommended.” In some cases, it said, security forces respond to the rebellion by “placing local towns under formal curfew or even shooting up the main streets at random.”

Though Dogubayazit was calm today, the underlying tension was still apparent. Approaching the center of town, I had barely made it past a string of cheap jewelry stores when a man approached me, eagerly.

“Hello,” he said, in English. We shook hands. “You just drove into town in that brown car, didn’t you? You’re staying in the hotel, in room 104.”

The secret police are working overtime, I thought.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“Um, I’m here to find out about Noah’s ark,” I said.

“Noah’s ark!” he repeated. “Well, if you want to learn about the ark you have to go to the green building at the end of this street. Go inside and up the stairs until you get to a dark room. Inside there’s another set of stairs. Go up those and you’ll find another dark room. In there you’ll find the man who knows everything about Noah’s ark.”

At first I thought he was joking, or laying a trap. I thanked him and continued strolling. I had heard enough horror stories—and seen enough tanks on the road into town—to ignore directions like these. I walked around for a few minutes, bought some plums in the market, and was heading back to the hotel when I stopped myself: Why exactly had I come here anyway?

Inside the green building I found the sagging staircase and proceeded to the second floor. The room was dark and smelled of discarded cigarettes. I hesitated for a minute, took a step forward, then reconsidered. I was just turning back when I heard a noise from above, then steps. Seconds later a figure appeared. It was a man in his early forties, lean, with black hair and an enormous bushy mustache that cascaded over his lips. His eyes were concealed by the gloom. He appraised me for a second, before saying, in perfect Oxonian English, “May I help you?”

“I was told you know about Noah’s ark,” I said.

He considered my answer. “But you were supposed to go up the second set of stairs.” I agreed.

“Maybe you don’t really want to know.”

He retreated as quietly as he had appeared and left me standing in the dark. This time I didn’t hesitate.

Upstairs, the man was just settling onto a low chair covered with carpets. He gestured for me to sit next to him. Between us was a table covered with books and a handful of photographs. He poured me a glass

of tea and we exchanged niceties. He was a native of Dogubayazit, a Kurd. Ten years ago he had served time in prison for his role as an insurgent. He refused to talk about the war and when I asked his name, he gestured toward his mustache: “Everyone calls me Parachute.” He was wearing a blue and white horizontal-striped T-shirt that, along with his dark hair, made him look like a Venetian gondolier. After a while I asked if it was possible to climb the mountain.

“It is forbidden,” he said. “Since 1991, nobody has been to the top.”

“Is there anything to see?”

“If you believe something, you can see. If you don’t believe, you cannot see.”

“What do you believe?”

“We believe. When we are children, we hear things. They tell us that this is Noah’s countryside. Even today, when something happens, the people say that it’s the luck of Noah.”

“Do you have the luck of Noah?” I asked.

“We know that something is there. We find something there.”

“I’m confused. You’re saying that you know something that everybody else does not know?”

“Yes.” His eyes were big, with deep bags under them. He didn’t move at all when he spoke. “I know it’s there. I find something there.”

“What is it that you found?”

“Ah.”

“You won’t tell me.”

“Hmm.”

“When will we hear?”

“One day you’ll hear.”

“And you’ll be famous around the world?”

He crossed his arms in front of his chest in a sly, self-satisfied way.

As Parachute well knew, almost since the Bible first appeared, stories of sightings of Noah’s ark have been a staple of Near Eastern lore, making it, in effect, the world’s first UFO. Josephus, the first-century historian, wrote of legends that the ark landed “on a mountain in Armenia.” In 678

C.E.

, Saint Jacob, after asking God to show him the ark, fell asleep on the mountain and awoke to find a piece of wood in his arms.

By the nineteenth century the sightings grew more elaborate. In 1887, two Persian princes wrote that they saw the ark while on top of the mountain, which is covered in snow year-round. “The bow and stern were clearly in view, but the center was buried in snow. The wood was peculiar, dark reddish in color, almost iron-colored in fact, and seemed very thick. I am very positive that we saw the real ark, though it is over 4,000 years old.”