War of the Whales (13 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

That winter, after Ken resigned from the

Regina Maris

, he and Diane toured the Bahamas in an inflatable Zodiac, camping on the beach or sleeping in the boat. They interviewed fishermen about local marine mammals and distributed sighting report flyers across the smaller cays. When they heard reports of “weird-looking dolphins with horns growing out of their heads,” Ken figured they must be referring to the stalked barnacles on Blainville’s beaked whales. Diane was well schooled in the local marine wildlife. She knew all about the dolphins and the sailfish and every creature on the reef. But she’ d never seen or even heard of beaked whales in the Bahamas. The afternoon they had a three-hour encounter near Abaco with a group of Blainville’s whales that circled their boat, they knew they had found their research home.

Regina Maris

, he and Diane toured the Bahamas in an inflatable Zodiac, camping on the beach or sleeping in the boat. They interviewed fishermen about local marine mammals and distributed sighting report flyers across the smaller cays. When they heard reports of “weird-looking dolphins with horns growing out of their heads,” Ken figured they must be referring to the stalked barnacles on Blainville’s beaked whales. Diane was well schooled in the local marine wildlife. She knew all about the dolphins and the sailfish and every creature on the reef. But she’ d never seen or even heard of beaked whales in the Bahamas. The afternoon they had a three-hour encounter near Abaco with a group of Blainville’s whales that circled their boat, they knew they had found their research home.

Diane conching during a camping trip to Schooner Cay, Bahamas, February 1991.

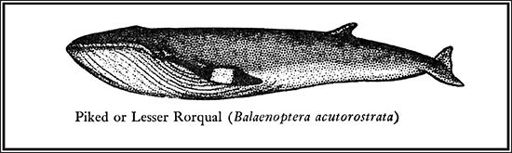

Beaked whales aren’t the most charismatic of marine mammals. They’re not nearly as sleek and beautiful as the black-on-white orcas. They can’t compete with the spectacle of a breaching humpback or a spyhopping gray whale. In truth, beaked whales do look a lot like “weird-looking dolphins,” on the rare occasions when they show themselves. But for marine mammal researchers in 1990, beaked whales were a virtual tabula rasa. Other than the large Baird’s species of the North Pacific, beaked whales were too small and elusive to interest whalers, so no one had ever bothered researching their behavior. The academic study of beaked whales was essentially a “dead” science, based on skeletal remains reconstructed by museum-based paleontologists and a few obsessive beachcombers such as Balcomb. Only one population of Atlantic beaked whales had ever been studied systematically—the northern bottlenose whales of Nova Scotia.

1

No one had ever surveyed the beaked whales in the Bahamas.

1

No one had ever surveyed the beaked whales in the Bahamas.

Ken and Diane launched the Bahamas Marine Mammal Survey in 1991. Even for most field researchers, it would have been tedious work: waiting and watching the water’s surface for hours at a time, holding camera and field notes at the ready for a fleeting glimpse of a dorsal fin or fluke. But for Ken and Diane, it was a custom fit. They shared the requisite combination of patience, keen observational skills, and a bottomless appreciation for the exquisite ecology of the Bahamas. And they never tired of each other’s quiet company on the water. It’s not an accident that so many marine mammal field researchers are husband-wife teams, and often childless. Ken and Diane became a hand-in-glove research couple, and the beaked whales became the object of their passionate, tireless attention. Over time, Ken and Diane learned subtle ways to enter the whales’ domain without scaring them off. By trailing along behind the boat with a mask and snorkel, Diane could spot the whales as they prepared to surface. Meanwhile, Ken built customized underwater microphones to gather audio cues of the whales’ movements.

In 1994 Ken proposed to Diane. They were married that summer on the beach in Snug Harbor on San Juan Island, and again for good measure in the Bahamas that fall.

Diane and Ken in Lichtenstein for her sister’s wedding, 1993.

By the winter of 2000, ten years into their survey, Ken and Diane had catalogued and studied the entire population of marine mammals in the northern Bahamas, including 150 Blainville’s, Cuvier’s, and Gervais’ beaked whales in residence. It was always a scramble to find enough funding to keep the boats on the water and film in their cameras. During the lean times, they ran bird-watching expeditions and eco-tours to pay the bills. Ken had finally found his true love and an equal partner in his life’s work. For the first time, he felt at home and at peace.

DAY 3: MARCH 17, 2000

Early the next morning, Balcomb and Ellifrit set off on the 65-mile trip to Water Cay in one of their inflatable boats, hoping that the carcass Balcomb had spotted from the air would still be salvageable. Three hours later, they anchored the boat 20 feet from shore and waded through the shallows to the beach. What was left of the whale was lying just out of the water on the sand.

It didn’t look like a very promising specimen. Sharks had ravaged the Cuvier’s, taking all of its tail and large chunks of its trunk and head meat. Balcomb took some measurements and calculated that it would have been a four-ton whale before the sharks hit it. While taking a skin sample for DNA, he realized they’ d caught a lucky break.

“It’s totally exsanguinated,” he said to Ellifrit. “Thanks to the sharks.” Ordinarily, the blood in the whale’s tissue and blubber becomes rancid as soon as the carcass is exposed to air. But because of the shark attack, this whale had completely bled out before it died, leaving its tissue and organs remarkably fresh. Best of all, its braincase was still intact!

With the sun approaching its apex, Balcomb was in a hurry to get the head off the carcass and into a freezer. When he made his first cut, some fluid seeped out of the whale and trickled down to the water. Within minutes, two tiger sharks had appeared offshore. Balcomb did his best to ignore them while Ellifrit stood guard in case a more aggressive bull shark showed up.

Ten minutes later, the head fell away from the trunk. “Okay, we’ve got it,” Balcomb said. “Let’s get this into the boat.”

Only then did it dawn on them that the tide had receded. The boat, which weighed about 2,500 pounds with its engine, would run aground if they tried to bring it closer to shore in the shallow water. Then they’ d be stuck until the next tide, and the head would be exposed to the elements for another five hours. They had no choice but to muscle the head through the shallows—which were now aswarm with sharks—and lift it into the boat.

The head weighed close to 300 pounds, and was so slippery with slime that they could barely grab hold of it. After a few practice lifts, they hoisted it to hip height and waded into the water. Floating the head out to the boat would have been relatively easy. But lowering the oozing specimen below the waterline wasn’t an option. Not if they hoped to get it past the sharks. Balcomb eyeballed the distance to the inflatable—only about 15 feet, now that the tide had receded—and made a quick count of the half dozen sharks swirling in the shallows. While he tried to calculate their odds, the head grew heavier in their arms. There was nothing to do but make a go for it. If things got out of control, he figured they could always chuck the head and run back to shore.

After exchanging a curt nod, they let loose a wild war cry and thrashed through the water toward the boat. They managed to keep the head above the water, but two of the sharks darted in to grab at bits of flesh that splattered into the shallows.

“On two!” Balcomb shouted as they drew close to the boat. “

One

. . .” They didn’t wait for two. With a heave, they rolled the head above the gunwale and into the boat. Then they dove in after it.

One

. . .” They didn’t wait for two. With a heave, they rolled the head above the gunwale and into the boat. Then they dove in after it.

They both looked down instinctively to confirm that their feet and legs were intact. All clear. But Balcomb knew they weren’t out of danger yet. Once—during a walrus count off Round Island, Alaska—he’ d been inside another inflatable boat that was reduced to flaps by an angry bull walrus when it attacked the boat and punctured all the forward tubes. He shivered at the thought of what would happen if the sharks started to bite into this one. Rolling to his knees, he lowered the engine into the water and yanked it to life.

The boat roared away from shore, pointing dead ahead for Les Adderly’s bait freezer.

10:00 P.M.

Sandy Point

Balcomb had to fly to Grand Bahama in the morning to meet Ketten’s flight, and he desperately needed some shut-eye. But first he wanted to check online to see if anything had been posted about the stranding.

Traditionally, cetacean field researchers were scattered as far and wide as the animals they studied, tracking belugas and bowheads in the Arctic, river dolphins in the Amazon and Southeast Asia, right whales on the Atlantic Coast, grays on the Pacific Seaboard, vaquita porpoises in the Sea of Cortez, and humpbacks migrating toward both poles in search of krill. Other researchers were based in academic labs on every continent. At one- or two-year intervals, those who could afford to travel would meet at international conferences to share their research and whale tales. Otherwise they toiled in far-flung isolation, communicating mostly through articles published in academic journals.

The internet changed all that.

In 1993 the University of Victoria in Canada established the first international Listserv for researchers and wildlife managers working with marine mammals. Overnight, decades of pent-up conversation bubbled over online. The marine mammal Listserv, known as MARMAM, became the town square for posting research data, conferences and speaker announcements, grant queries, job notices, rumors, and gossip. Heated debates broke out from time to time, but, for the most part, MARMAM was a forum for informed conversation among hundreds, and then thousands, of researchers, bureaucrats, and animal protection activists around the globe.

On the night of March 17, Balcomb logged on to MARMAM to find that neither the Bahamian nor US Fisheries departments had posted anything about the stranding. No scientists anywhere had. Balcomb stared at the screen. He pulled the prints of the USS

Caron

out of his desk drawer. He stared at photos of the Blainville’s, its severed head matted with flies. Then he started to type.

Caron

out of his desk drawer. He stared at photos of the Blainville’s, its severed head matted with flies. Then he started to type.

Post to:

MARMAM Newsgroup

“Just the facts, ma’am,” Balcomb intoned quietly. “No need to editorialize.” He continued typing.

From:

Ken Balcomb, Bahamas Marine Mammal Survey, Abaco, Bahamas

Subject:

Whale Strandings in the Bahamas Islands

Date:

17 March 2000

The following is a summary of whale and dolphin stranding events in the northern Bahama Islands during March 15, 2000. We were directly involved in assisting with rescue or necropsy during nine of these events and can document them in some detail.

He methodically detailed the location and time and species of each of the reported strandings based on the logs they had compiled over the past three days. Then he added a final paragraph:

It is worth noting that we have been gathering reports of marine mammal strandings, and have been conducting field studies of living marine mammals in the Bahama Islands since 1991; the stranding rate of cetaceans is typically on the order of one or two reported per year in the entire island chain. Beaked whale strandings are particularly rare.

When he was finished, Balcomb reread his entry twice. He took a breath and exhaled. Then he clicked the Submit Post button.

7

“Unusual Mortality Event”

A whale on a beach has always been a mystery that cried out for explanation. Ancient coastal dwellers from the South Pacific to the Bering Sea interpreted strandings as a bounty of food and other blessings sent to them by their gods. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle remarked on the conundrum of beached whales in his

Historia Animalium

: “It is not known for what reason they run themselves aground on dry land; at all events it is said that they do so at times, and for no obvious reason.”

Historia Animalium

: “It is not known for what reason they run themselves aground on dry land; at all events it is said that they do so at times, and for no obvious reason.”

Other books

Burning Darkness by Jaime Rush

Mountain Echoes (The Walker Papers) by C.E. Murphy

Rebecca Hagan Lee by Gossamer

Pushing Up Bluebonnets by Leann Sweeney

A Whisper in the Dark by Linda Castillo

Freeing Him: A Hart Brothers Novel, Book 2 by A.M. Hargrove

Love Takes Hold: The Helena's Grove Series Book 3 by Ivy Alexander

The Bishop's Daughter by Wanda E. Brunstetter

For the Right Reasons by Sean Lowe

Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse, David Horrocks, Hermann Hesse, David Horrocks