War of the Whales (33 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

As soon as the image began to take shape on the screen, the tension went out of the room, and the chill departed from Ketten’s voice. “This is my favorite part,” she said, “when I get my very first look inside. It’s wonderful, isn’t it?”

It

was

wonderful. Balcomb and Claridge were transfixed. The lines of pixels gradually grew in detail to reveal the structure of the ear bone in all its elegance: the spiral nautilus shape of the cochlea leading to the three small ear bones of the auditory ossicles. Ketten manipulated the computer’s mouse like a digital scalpel to pare away layers of tissue and fully articulate the bony structures.

was

wonderful. Balcomb and Claridge were transfixed. The lines of pixels gradually grew in detail to reveal the structure of the ear bone in all its elegance: the spiral nautilus shape of the cochlea leading to the three small ear bones of the auditory ossicles. Ketten manipulated the computer’s mouse like a digital scalpel to pare away layers of tissue and fully articulate the bony structures.

“Now watch this: it’s so great!” With a few keystrokes, the two-dimensional image began to rotate and reveal itself in three dimensions. The ear bones revolved like a jeweled tiara in a Cartier display window.

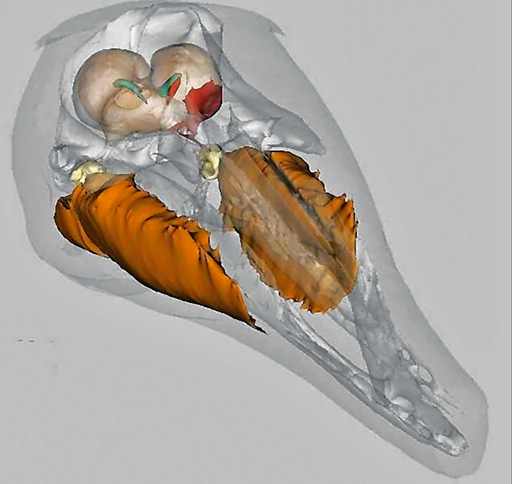

“Now, here’s the coolest part of all,” she said in a hushed voice, as if speaking too loudly might break the spell. “We can colorize the specimen by density.” With another keystroke sequence, Ketten transposed the monochromatic model into vivid greens and yellows. “The CT can differentiate the density range of bones, soft tissue, and fluids—even air pockets,” she explained.

Ketten pointed at red lines in both ears. “Look what we have here: the pattern of hemorrhaged blood is almost identical bilaterally. If we saw the blood only in one ear, that would suggest a postmortem trauma, or simply evidence of the whale lying on one side postmortem. But this bilateral hemorrhage is a clear sign that the ears were traumatized

before

the whale hit the beach.”

before

the whale hit the beach.”

They replaced the ears with the Blainville’s head, which took a full hour to image.

“Look,” she said, when the details were filled in and colorized. “The same hemorrhagic bleed pattern in these ears.” After the Blainville’s, they scanned the Cuvier’s head and found blood pooling around the brain.

3D reconstruction from CT scans of the Blainville’s beaked whale from Cross Harbor. The skin and skull are rendered transparent to show key features: pooled blood inside the skull on the left side (dark red), the brain (pink), two brain ventricles (blue), the ear bones (yellow), acoustic jaw fats (orange).

It was well after midnight when they hoisted the dolphin onto the scanner. Claridge reached out to touch the dolphin through her latex glove. It was utterly transformed from the warm, smooth animal that convulsed and died in her arms two weeks earlier. Now it was stiff and lifeless, an ice sculpture of a dolphin.

An hour later, digitally rendered on the CT’s monitor, the dolphin was reincarnated as a white skeleton floating inside a pale blue shell of skin. A close-up of the head showed its brain in pink, suspended above two orange lobes of auditory fat along the jawbones. Nestled underneath the lobes, the inner ears stood out as bright red knobs. Claridge, who had observed dolphins in the wild all her life, had the eerie feeling that she had never truly seen one before this.

3D reconstruction from CT scans of a whole Short-beaked Common Dolphin (

Delphinus delphis

) showing the animal’s external surface and below, with a transparent skin, the skeletal anatomy.

Delphinus delphis

) showing the animal’s external surface and below, with a transparent skin, the skeletal anatomy.

By three in the morning, they had completed their work, and Carl had packed all the specimens into the lab’s freezer. Ketten was still dictating her findings. “The patterning of the hemorrhages therefore suggests strongly that a cerebrospinal fluid ‘squeeze’ from an intense pressure event was the source of inner ear blood in these animals . . . The inner ear pathologies demonstrated on the scans are consistent with observed pathology in ears exposed to exceptionally intense impulsive sources . . . The pattern of damage is consistent with acoustic trauma, but a number of other causes are equally possible and cannot be ruled out at this stage of analysis.”

Just before dawn, the four of them drove the specimens down to Woods Hole, two hours south of Boston. They were giddy with exhaustion by the time they reached the Redfield Laboratory on Water Street. When they’ d moved the specimens inside the walk-in freezer, Ketten closed the freezer door and sealed it with a padlock. Final chain-of-custody papers were signed all around. “And we’re done,” said Ketten, sealing the documents into a large envelope. With a mock ceremonial bow, she presented Balcomb with another envelope containing a full set of CT scans. She told them she’ d be in touch as soon as they had a date scheduled for the full physical necropsy.

Balcomb would have liked to linger in Woods Hole and tour the facilities. But they had a noon flight back to Miami, and Ketten had a class to teach in an hour. They said their good-byes on the steps of the lab, and Carl drove them back to Logan Airport.

Before her class began, Ketten called Bob Gisiner to report her preliminary findings. She confirmed that the heads were now in secure custody at her Woods Hole lab, and that Balcomb and Claridge would soon be on a plane back to the Bahamas.

SANDY POINT, ABACO ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS

A week after his return to Abaco, Balcomb couldn’t stop thinking about the heads back in Woods Hole. He’ d tried calling Ketten to find out the date of the necropsy, but he couldn’t catch her in. And she didn’t call him back. Gisiner wasn’t taking or returning his calls either. The only person he could reach was Gentry, who was sounding more and more like an assigned handler, counseling patience and team play and trust that things would come out right in the end.

Without the whales to survey, Balcomb and Claridge were at loose ends. Each of their daily trips to the canyon in search of beaked whales had ended in disappointment.

Sitting on the back porch at the end of another restless, purposeless day, Balcomb gazed out across the canyon in the direction of the AUTEC testing range. He wondered what sounds the Navy hydrophones mounted on the sea floor had recorded the night of the stranding. He was haunted by a memory from his final Navy tour in Japan. His wife at the time, Camille, was researching the 400-year-old dolphin fishery at the small coastal town of Taiji. Though it was normally closed to Westerners, he and Camille had arranged to witness the seasonal dolphin drive hunt.

A flotilla of a dozen small boats arranged itself into a straight line just outside the mouth of the cove. A short time later, a large pod of dolphins approached, and the line of boats opened out to herd them inside the cove. Then the boats closed formation, sealing the mouth of the cove. Each boatman lowered a steel pipe halfway into the water and began banging the top half with a second steel pipe. From the shore, Ken and Camille could hear the steel pipes clanging loudly in unison. Balcomb knew that underneath the water’s surface, the sound was converging into a wall of high-decibel noise. Then the boats began to move toward the shore, driving the dolphins ahead of them and into the shallows.

Ken and Camille watched in horror as the men leapt from their boats into the churning waters. They culled a few young females for export to foreign marine parks. They stabbed the remaining dolphins with spears, dragged their thrashing bodies onto the beach, and slit their throats. The men didn’t wait for the dolphins to die before butchering them into steaks bound for fish markets across Japan. The shallows turned dark red with blood, and the air filled with the shrieks of dozens of dying dolphins.

Twenty-five years later, standing on another beach a world away from Taiji, Balcomb could still hear the knell of the steel pipes, could still see the panicked dolphins fleeing ahead of the acoustic storm, rushing toward the oblivion of the beach.

PART THREE

THE RELUCTANT WHISTLE-BLOWER

What if the catalyst or the key to understanding creation lay somewhere in the immense mind of the whale? . . . Suppose if God came back from wherever it is he’s been and asked us smilingly if we’ d figured it out yet. Suppose he wanted to know if it had finally occurred to us to ask the whale. And then he sort of looked around and he said, “By the way, where are the whales?”

—Cormac McCarthy

, Of Whales and Men

, Of Whales and Men

17

A Mind in the Water

When the Navy began studying cetacean biosonar in the late 1940s, the only people who cared about saving the whales were whalers.

By the end of World War II, it had become clear to everyone in the whaling industry that 50 years of unbridled slaughter had decimated populations around the world. Many commercial species were already depleted and threatened with extinction. Two late-nineteenth-century inventions by the Norwegian whaler Svend Foyn had reduced even the most gigantic whales to helpless prey. In 1863 he introduced the first steam-powered whaling ship that could overtake even the largest and fastest of the great whales: blues, fins, and seis that could outswim any ship under sail. A few years later, he demonstrated how his deck-mounted harpoon canon, firing explosive grenades, could stop the heart of a 100-foot-long leviathan.

Things got progressively worse for whales in the twentieth century. Demand for whale oil to manufacture glycerin bombs spiked during World War I, and after the war, the process of hydrogenating whale oil created a boom market for its use in margarine. By the 1920s, fleets of floating factory ships were killing and processing whales at sea with lethal efficiency. Throughout the 1930s, tens of thousands of great whales were harvested each year. In 1939 alone, whalers killed almost 40,000 blue whales.

Whaling was suspended during World War II, as shipping lanes shut down and many whaling ships were drafted into service as military cargo vessels. Still, the war took a deadly toll on whales caught in the cross fire of major sea battles in the Atlantic and Pacific. Millions of tons of explosives were detonated in the oceans, including hundreds of thousands of antisubmarine depth charges. Air forces and navies on both sides of the conflict made a practice of using passing pods for target practice. In the aftermath of the war, industrious whalers adapted military sonar to locate, drive to the surface, and herd their prey—but there were indisputably far fewer whales left to hunt.

1

1

Other books

Espía de Dios by Juan Gómez-Jurado

Nice Girls Don't Ride by Roni Loren

The Next Full Moon by Carolyn Turgeon

D.I.Y. Delicious: Recipes and Ideas for Simple Food From Scratch by Vanessa Barrington, Sara Remington

Zombie Castle (Book 1) by Harris, Chris

The Secret Lives of Emails.docx by A.J. Ramsey

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set by Gail Carriger

Night Vision by Yasmine Galenorn

The Flemish House by Georges Simenon, Georges Simenon; Translated by Shaun Whiteside