War of the Whales (57 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

Balcomb believed that the lawsuits had been the right medicine at the right time. It had taken that kind of 4x4 across the forehead to make the Navy see reason and put some limits on its sonar exercises. But he wasn’t convinced that the problem was going to get resolved in the courts. As a Navy veteran who understood military chain of command, Balcomb considered it the responsibility of the president, as commander in chief, to set things straight. The president couldn’t issue the Navy a waiver that exempted it from the law, the way Bush had tried to do. But the president sure as hell could order the fleet to

obey

the law. Back in the summer of 2000, immediately following the Bahamas stranding, he’ d written President Clinton and asked him to direct Navy Secretary Danzig to permanently exclude known whale habitats from sonar training exercises. He’ d written the same letter to George W. Bush in 2001. Now he would write to the new president and ask him to intervene.

obey

the law. Back in the summer of 2000, immediately following the Bahamas stranding, he’ d written President Clinton and asked him to direct Navy Secretary Danzig to permanently exclude known whale habitats from sonar training exercises. He’ d written the same letter to George W. Bush in 2001. Now he would write to the new president and ask him to intervene.

Balcomb wasn’t so naïve as to think that President Obama would follow his advice. But he still had to write the letter. That was his job. To write to politicians. To talk to journalists and to anyone else who would listen. To keep tabs on the whales in Puget Sound and on the Navy ships in the area. To keep beating the drum as loud and as long as he could.

EPILOGUE

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

—Mahatma Gandhi

FIVE YEARS LATER; AUTUMN 2013

Joel Reynolds had been willing to suspend sonar lawsuits for a while, but he was constitutionally incapable of “cooling off.” He immediately threw himself into a fight to stop development of the Pebble Mine in southwest Alaska, which—if built, as proposed, at the headwaters of the Bristol Bay watershed—promised to become one of the largest open-pit copper and gold mines anywhere, generating some billion tons of contaminated mining waste and threatening the most productive wild salmon fishery left in the world.

At Tejon Ranch, Lebec, California, Reynolds announces the agreement he negotiated with the ranch and state of California to preserve 90 percent of the 270,000-acre Tejon Ranch—with California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in the background, 2008.

It was a trademark, Joel Reynolds-led NRDC campaign, involving alliances with local groups on the ground, public pressure on the multinational backers from its membership, and media attention generated by NRDC trustee Robert Redford. Reynolds held face-to-face meetings with the mining interests, and confronted their lobbyists on Capitol Hill. Within four years of Reynolds and NRDC’s entering the fray, all three of the major mining company partners had pulled out, leaving only a small Canadian company remaining, in search of partners. After an in-depth EPA study found that large-scale mining threatened the Bristol Bay region with “catastrophic” risks, Reynolds—recently elevated to western director of NRDC—called on that agency to use its authority under the Clean Water Act to stop the project. In February 2014, EPA initiated a formal process to do just that.

Meanwhile, Ken Balcomb had also refused to cool off. In 2009, when the Navy introduced proposals to build a mine-warfare range in its Northwest Training Range Complex, Balcomb spearheaded the local protests. The Puget Sound orca population continued to struggle following the crash of their prey species, the Chinook salmon. The pods had to venture farther and farther afield each season for food. Since underwater explosives would further disrupt their foraging patterns, Balcomb pressed Fisheries to enforce the “endangered” protections the orcas were due under the Endangered Species Act.

Dozens of local groups lodged protests with Fisheries, and NRDC submitted a 20-page legal and scientific declaration. While the suit was pending, Michael Jasny, who had recently been promoted to head of NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project, helped Balcomb convene a cross-border conference with Canadian conservationists and Fisheries officials to implement a coordinated plan for protecting both the Southern and Northern Communities of orcas.

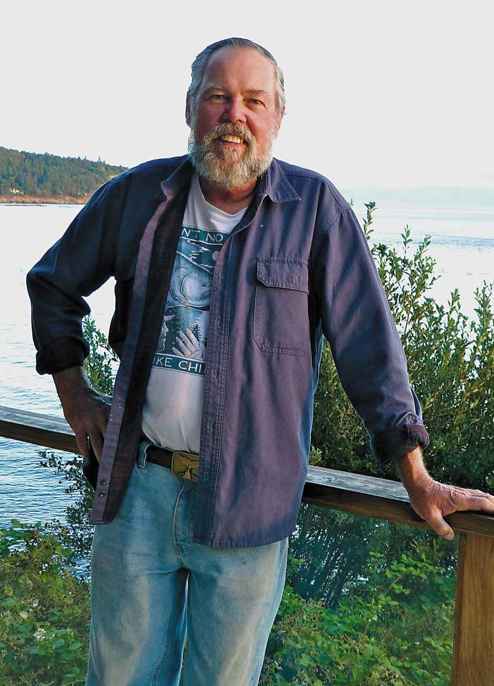

Ken Balcomb on the deck of his house—and headquarters of the Center for Whale Research—Smugglers Cove, San Juan Island, Washington, 2010.

• • •

In the five years since the Supreme Court decision, consensus had built inside the research community—even among Navy and Fisheries researchers—about the threat that noise pollution, including military sonar, poses to whales. Research into whale distribution and behaviors—funded largely by ONR as part of the sonar settlement—revealed that much lower sound levels than previously believed cause whales to change their migration patterns and eating and communication habits. Most importantly, chronic noise pollution depresses their reproduction. In particular, research into beaked whale populations in the waters off California—as well as a study of beaked whales in the Bahamas published by Diane Claridge as part of her PhD thesis—documented a dramatic drop-off in reproductive health.

1

1

Meanwhile, whales continued to mass-strand—sometimes in alarmingly high numbers—in the presence of sonar.

Sixty dolphins stranded along the coast of Cornwall, England, in 2008, by far the largest marine mammal mortality ever recorded in British waters. The forensic investigation involving 24 experts from five countries and multiple government agencies identified nearby exercises being conducted by the Royal Navy—in collaboration with American Navy forces—as the only possible cause of the strandings.

2

2

At least ten, and possibly dozens, of Cuvier’s beaked whales stranded or washed ashore dead on the Greek island of Corfu in December 2011. The stranding coincided with a major Italian navy exercise using sonar in the nearby Ionian Sea.

3

3

And on May 30, 2008, a pod of more than 100 melon-headed whales stranded in a mangrove estuary on the northwest end of Madagascar. Despite intensive rescue efforts by both local authorities and experts from around the world, 75 of the whales died on the shore. An independent review panel of five scientists appointed by the International Whaling Commission spent several years examining evidence. They “systematically excluded or deemed highly unlikely” nearly every other possibility before concluding in their final report (to which Darlene Ketten appended a 26-page analysis of the specimen CT scans) that these deep-water whales had been driven ashore by an underwater mapping sonar that the ExxonMobil Corporation was using nearby to search for oil and gas deposits.

4

4

Then in 2012 the Navy filed public notice of its plans for expanding exercises on its Undersea Warfare Training Ranges up and down its East and West Coast ranges. In addition to increasing its sonar exercises on both coasts and in Hawaii, the Navy proposed new mine warfare and firing ranges for torpedoes and other underwater explosive ordnance. The Navy’s own Environmental Impact Statements predicted millions of marine mammal “takes,” including nearly one thousand deaths and 13,000 serious injuries. For the first time, the Navy included explosives testing along with sonar trainings in its projections, which gave a more comprehensive picture of the overall impacts of the expanded activities.

Fisheries was preparing to approve permits for the Navy’s expanded undersea warfare activities across its ranges by January 2014, and it was already girding for the response—not just from NRDC, which had resolved to return to court to challenge the permits, but also from a host of national, international, and grassroots organizations.

*

*

SEPTEMBER 7, 2013

Smugglers Cove, San Juan Island, Washington

Reynolds had never visited Balcomb at his research station home on San Juan Island, but now that he was heading back into the fight against the Navy and Fisheries, he wanted to check in with Balcomb in person and ask him to re-up. With his intensive involvement in the Pebble Mine campaign, Reynolds was frequently traveling through Seattle. So a week earlier, he’ d called to see if Balcomb would be around to talk. “I’m still here,” said Balcomb. “So are the orcas. Come on over.”

The last time Reynolds had seen him—when they were both members of a congressionally mandated advisory group meeting on ocean noise pollution some years earlier—Balcomb was undergoing treatment for his prostate cancer and looked like hell. When Reynolds pulled up behind his cedar shingle house on Smugglers Cove and Balcomb greeted him at the door, Reynolds was reassured by how ruddy and robust he looked at 73 years of age. He was wearing jeans and one of his trademark T-shirts—“Pacific Beach: A quaint little drinking town with a fishing problem”—along with his customary wide, toothy grin.

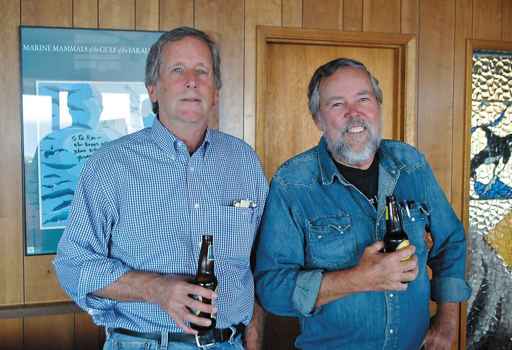

Reynolds and Balcomb at Smugglers Cove, San Juan Island, Washington, September 2013.

Reynolds had recently taken his two teenaged daughters to a screening of

Blackfish

, a documentary about captive orcas in which Balcomb appeared. When they heard that their father would be visiting Balcomb, they said he had to come back with a picture. So Balcomb set up a camera on a tripod and shot the two of them against a backdrop of whale skulls that lined the foyer of the house.

Blackfish

, a documentary about captive orcas in which Balcomb appeared. When they heard that their father would be visiting Balcomb, they said he had to come back with a picture. So Balcomb set up a camera on a tripod and shot the two of them against a backdrop of whale skulls that lined the foyer of the house.

They updated each other on their personal lives. Balcomb was healthy again, having had follow-up treatment for his prostate cancer. He had a couple of girlfriends who moved in and out of Smugglers Cove, seasonally, like the whales. Balcomb acknowledged, with a smile, that he wasn’t sure whether the women were coming to see him or the orcas.

Now, in mid-September, the summer interns and most of the whales had departed for the season. Dave Ellifrit had moved to San Juan Island in 2008 and bought a house. Other researchers had married each other, divorced, and remarried other young colleagues on the team. Balcomb joked that it was harder to keep track of the researchers’ couplings and uncouplings than those inside the resident orca pods.

Reynolds told him about his fiancée and showed him photos on his phone. Jenny was an environmental chemistry professor at UCLA whom he’ d been dating for several years. They’ d recently gone to city hall to get a marriage license. But the day they showed up, it was swamped by hundreds of gay and lesbian couples who’ d arrived for licenses during the week after the recent Supreme Court ruling that upheld California’s same-sex marriage law. The line was out the door and around the block, so they decided to go out for lunch and return another day.

Balcomb led him on a tour of the grounds, including the 1929 Ford and 1956 Chevy parked in nearby sheds. Back inside, he gave Reynolds a tutorial on some of the finer points of beaked whale hearing, using the three skulls in his living room as teaching props. Then Reynolds sat down at a white piano set incongruously among the skulls; the piano had come with the house, and Balcomb liked having it around as a reminder of his chanteuse mother. Reynolds played a country-and-western song he’ d recently written about an old red pickup truck and a woman driving away at dawn with his heart in the flatbed.

Other books

Cassandra Kresnov 04: 23 Years on Fire by Joel Shepherd

The Wild Road by Jennifer Roberson

We Are All Made of Molecules by Susin Nielsen

Cosmo Cosmolino by Helen Garner

Coffee at Luke's: An Unauthorized Gilmore Girls Gabfest (Smart Pop Series) by Jennifer Crusie, Leah Wilson

Dread Murder by Gwendoline Butler

Demonically Tempted (Frostbite) by Kennedy, Stacey

Don't Tell by Eve Cassidy

A Gathering of Widowmakers (The Widowmaker #4) by Mike Resnick

Love With a Scandalous Lord by Lorraine Heath