War: What is it good for? (19 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

In the West, this story got the Romans to Rome; in the East, it got the Chinese to Chang'an and the Indians to Pataliputra. Each, in its way, was a similar sort of place: not very democratic, but peaceful, stable, and prosperous. Caging, not culture, was the driving force, and it created a productive way of war, not a Western way.

Wider Still and Wider

Rome, Chang'an, and Pataliputra still had a long way to go to get to Denmark. Romans crucified criminals and killed gladiators for fun; Chinese and Indians flocked to public beatings and beheadings. Torture was legal everywhere and slavery widespread. These were violent places.

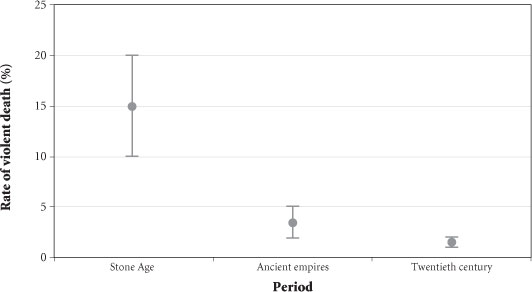

That said, though, the evidence we have seen in the last two chapters suggests that the ancient empires had already come a long way from Samoa. Anthropological and archaeological data suggest that roughly 10 to 20 percent of the people in Stone Age societies died violently; historical and statistical data show that just 1 to 2 percent of the twentieth-century world's population died violently. The risk of violent death in the Mauryan, Han, or Roman Empire probably lay somewhere between the modern 1â2 percent and the prehistoric 10â20 percent, and my guess (given the near-total lack of quantifiable information, it can only be that) is that it was nearer the lower than the upper end of this range.

I say this because of some numerical modeling I did in my two most recent books,

Why the West Rulesâfor Now

and

The Measure of Civilization

. In these I calculated a rough index of social development, measuring societies' abilities to organize themselves and get things done in the world. Social development does not correspond exactly to the strength of Leviathan, but it comes pretty close.

The scores on this index suggest that by the time of the battle at the Graupian Mountain in

A.D.

83, Roman social development was at roughly the same level that western Europe would regain in the early eighteenth century

A.D.

Development in Han China peaked a little lower, around about where western Europe would be in the late sixteenth century, when Shakespeare was beginning to make his name. Mauryan development peaked a little lower still, perhaps around the level western Europe would reach in the fifteenth century.

The implication of these scores, I think, is that while the ancient empires did not get to Denmark, they did get to where western Europe would be between about

A.D.

1450 and 1750. And if that assumption is valid, it might also be the case that rates of violent death in Roman, Han, and Mauryan times were comparable to those in fifteenth- through eighteenth-century western Europe, pointing us toward a figure above 2 but below 5 percent (

Figure 2.9

).

Figure 2.9. How far to Denmark? My estimates of rates of violent death, showing the range for each period (10â20 percent for Stone Age societies, 2â5 percent for ancient empires, and 1â2 percent for the twentieth-century world) and its midpoint

This is, of course, a very rough-and-ready estimate, with a lot of ifs piled on top of each other. At the very least, there must have been huge variations, both within and between the ancient empires. The risk of violent death might still have been closer to 5 percent than to 2 when Rome fought Carthage in the third century

B.C.

and might have drifted back up

toward 5 percent during the tumultuous first century

B.C.

But in the second century

A.D.

, which Gibbon singled out as Rome's golden age, a figure at the bottom end of the 2â5 percent range seems much more likely.

Neither the Han nor the Mauryan Empire seems to have gone quite this far, and the less well-documented Parthian Empire could well have stayed above 5 percent. But overall, the conclusion must be that by the late first millennium

B.C.

, all the ancient empires were well on their way toward Denmark. Rates of violent death might have fallen by three-quarters since caging began in the lucky latitudes.

It was a dramatic decline, to be sure, but it took nearly ten thousand years. This might in itself explain why Cicero and Calgacus disagreed so wildly over what Rome's wars had wrought. Calgacus, a warrior in a preliterate society, looked only at recent history andâquite reasonablyâsaw nothing but death, destruction, and wastelands. Cicero, an intellectual in a great empire with a long history, looked back across seven centuries of expansion and saw that it added up to a productive way of war that had gradually made everyoneâconquerors and conquered alikeâsafer and richer.

When Agricola led his armies back to their camps at the end of

A.D.

83, he was confident that he was waging productive war. He might have left a wasteland after the battle at the Graupian Mountain, but he would be back, and in his wake would come farmers, builders, and traders. They would plow up fields, lay down roads, and import Italian wine. Wider still and wider would the empire's bounds be set; farther still and farther would peace and prosperity spread.

At least, that was the plan.

Footnotes

1

Also available as a (highly) dramatized thirty-hour Hindi television series, with English subtitles (

http://intellectualhinduism.blogspot.com/search/label/Chanakya

).

2

Paleoclimatologists technically date the end of the Ice Age proper around 12,700

B.C.

but regularly treat the twelve-hundred-year mini ice age known as the Younger Dryas (10,800â9600

B.C.

) as the Ice Age's final phase.

3

echnically, domestication means the genetic modification of one species so that it can only survive with continued intervention from another species, as happened when human intervention turned wolves into dogs, wild aurochs into cattle, and wild rice and barley into domesticated versions that depend on humans to harvest and replant them.

4

My candidate for the most peculiarly named conflict in history. The casus belli was a Spanish coast guard's decision to cut the left ear off a British merchant named Robert Jenkins in 1731. For eight years the British government did nothing about this but in 1739 decided war was the only possible response.

5

The San language is full of clicks, glottal stops, and other sounds not used in English, so anthropologists' accounts are littered with names beginning with â , !, /, and even //.

6

When the Helvetii first decided to invade, a man named Orgetorix was trying to make himself their king, much as Dumnorix was doing among the Aedui. Things came to the verge of civil war before Orgetorix abruptly (and suspiciously) died.

7

A room entered through a trapdoor in the roof.

8

I am showing my age, but to my mind there are few better examples of discipline in the face of violence than Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier forcing themselves back into the ring in 1975, concussed and half-blinded, for round after round of vicious assaults. Ali described the experience as “next to death.”

9

In

A.D.

2004, after thirty-eight centuries of horse slaughter, a monument to all the animals killed in war was unveiled on Park Lane in London. It has a simple inscription: “They had no choice.”

10

Technically, blades less than fourteen inches long are daggers, those of fourteen to twenty inches are dirks, and anything in the twenty-to-twenty-eight-inch range is a short sword. Proper swords are over twenty-eight inches long. (The blade of the famous Roman short sword, the

gladius,

was typically twenty-four to twenty-seven inches long.)

11

The second and third ranks were chariots and cavalry (in that order).

3

THE BARBARIANS STRIKE BACK: THE COUNTERPRODUCTIVE WAY OF WAR,

A.D.

1â1415

The Limits of Empire

The plan did not pan out. Instead of coming back to Caledonia, Agricola settled into retirement in the Italian sunshine. The cream of his army was redeployed to the Balkans, and the remainder pulled back into a string of forts across northern England. Their days of conquest were over.

Since 1973, archaeologists have painstakingly excavated a set of noxious garbage dumps at Vindolanda, one of these Roman fortresses. In one pit, so drenched with urine and feces that oxygen could not penetrate it, they found hundreds of soldiers' letters, written in ink on wooden boards. The earliest go back to the 90s

A.D.

, just after Agricola's campaigns. There are a few highlights, including an invitation to a birthday party, but most exude nothing so much as boredom. Roman soldiers in first-century Britain apparently thought about much the same things as American soldiers in twenty-first-century Afghanistan: news from home, the foul weather, and the eternal quests for beer, warm socks, and tasty food. Garrison life has not changed much in the last two thousand years.

In these forts the remnants of Agricola's army stayed for the next forty years. They wrote home, they fought deadly little skirmishes with Caledonians (“there are lots of cavalry,” another urine-soaked memo from Vindolanda observes), andâabove allâthey waited. Only in the 120s

A.D.

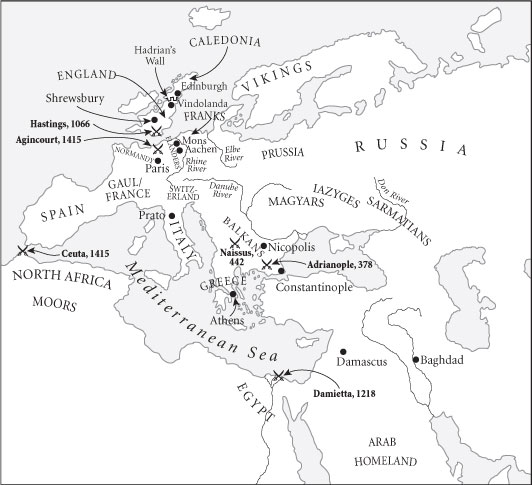

did they move on, but not to new triumphs. Rather, the emperor Hadrian set them to building the great wall across Britain that bears his name. Rome had abandoned the conquest of the North (

Figure 3.1

).

Figure 3.1. The limits of empire in the West: sites in western Eurasia mentioned in this chapter

As Tacitus saw it, all this came about because the emperor Domitian was jealous of Agricola's triumphs. Perhaps he was right, but it was the ruler's job to see the big picture, and in the 80s

A.D.

that picture was turning distinctly dark. Even before the battle at the Graupian Mountain, Domitian had been withdrawing contingents from Agricola's legions to bolster defenses along the Rhine, and when the emperor pulled the best troops out of Britain in

A.D.

85, it was to plug gaps in the crumbling Danube frontier. This strategic pivot worked, and the river frontiers held. But Domitian drew a radical conclusion from it: that Rome no longer had much to gain from productive war.

Romans had been drifting toward this conclusion for nearly a century. Between 11

B.C.

and

A.D.

9, the emperor Augustus had methodically pursued what wouldâhad it succeededâhave been the most productive war Rome ever fought, pushing the frontier northeast to the Elbe River to

swallow up what is now the Netherlands, a slice of the Czech Republic, and almost all of Germany. But it ended in disaster: stretched out along ten miles of winding paths through dark forests, their bowstrings and armor soaked by torrential rains, the Romans were betrayed by their guides and ambushed. In the three-day running battle that followed, about twenty thousand Romans were killed, andâeven more horrifying to Rome's warrior classâthree legionary standards were captured. Roman armies took revenge with a decade of rape, pillage, and killing, but in the end the disaster prompted them to rethink the empire's grand strategy. Conquest seemed to be more trouble than it was worth. When Augustus died in

A.D.

14, his will contained just one piece of strategic advice: “The empire should be kept within its boundaries.”

Most of the men who followed him onto the throne did what he said. Claudius broke the rule by invading Britain in

A.D.

43, only for Domitian to close the campaigns down in the 80s. Trajan broke it more flagrantly after 101, overrunning much of modern Romania and Iraq, but when Hadrian succeeded him in 117, abandoning many of these gains was almost his first act.

Rome's emperors were groping their way toward a profound strategic insight, which would be formalized seventeen centuries later as one of the basic maxims of war-making by Carl von Clausewitz, arguably the greatest of all military thinkers. “Even victory has a culminating point,” Clausewitz observed. “Beyond that point the scale turns and the reaction follows with a force that is usually much stronger than that of the original attack.” Whether Clausewitz learned this from his own career (he witnessed Napoleon's disastrous experience with culminating points in 1812 at first hand, fighting for Russia because his native Prussia had dropped out of the war) or from his deep study of Rome's wars remains unclear. It is perhaps no coincidence, though, that Edward Luttwak, the modern strategist who has looked hardest at the paradoxical nature of culminating points, has also written the best book on Roman grand strategy. “In the entire realm of strategy,” Luttwak notes, “a course of action cannot persist indefinitely. It will instead tend to evolve into its opposite.”

For centuries, wars of conquest had (over the long run) been productive, creating larger empires that gradually made people safer and richer. But as ancient imperialism neared its culminating point, the back-to-front logic of war threw everything into reverse. War did not just stop being productive; it turned downright counterproductive, breaking down large societies, impoverishing people, and making their lives more dangerous.

The first sign that the ancient empires were approaching their culminating points was the onset of diminishing returns to conquest. So long as the Romans stayed near the Mediterranean Sea, size was no great issue, because water transport was relatively cheap and fast. But in a world where armies moved at the pace of an oxcart, pushing inlandâinto Germany, Romania, and Iraqâdrove costs upward. It cost almost as much to load a ton of grain onto carts and drag it ten miles overland as it did to ship it from Egypt to Italy, and despite the Romans' famous roads, by the first century

A.D.

the gains from warâwhether measured in gold or gloryârarely seemed to justify the costs.

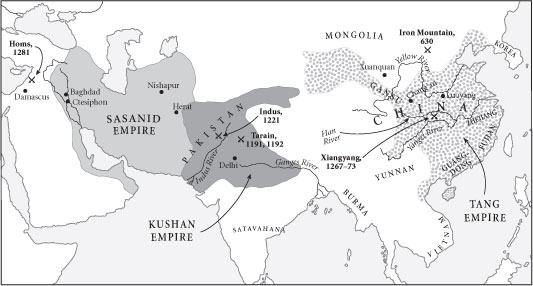

At the other end of Eurasia, China's rulers were wrestling with the same calculus (

Figure 3.2

). Between about 130 and 100

B.C.

, Han armies had gone on a rampage, bringing into the empire what are now the Chinese provinces of Gansu, Fujian, Zhejiang, Yunnan, and Guangdong, as well as a great chunk of central Asia, most of Korea, and a piece of Vietnam (not to mention punitive campaigns deep into Mongolia). After 100

B.C.

, though, the feeling grew in the court at Chang'an that the cost in blood and treasure was just not worth it. The farther the armies got from the Yellow and Yangzi Rivers, the higher the costs rose and the lower the benefits fell. There were renewed pushes into central Asia and toward Burma in the 80s and 70s

B.C.

, then another lull, and in the aftermath of a terrible civil war in

A.D.

23â25 expansion more or less ended.

Figure 3.2. The limits of empire in Asia: sites mentioned in this chapter, and the greatest extents of the Sasanid (around

A.D.

550), Kushan (around

A.D.

150), and Tang (around

A.D.

700) Empires

By the first century

A.D.

, the Roman and Han Empires had conquered similar areas (around two million square miles each) and ruled similar populations (fifty to sixty million people each). The problems their emperors faced were similar too, and both sets of overlords reached the same conclusions. They recalled their ambitious generals, built walls along their increasingly rigid frontiers, and settled hundreds of thousands of soldiers in forts much like Vindolanda. Some sites on China's arid northwest frontier in fact outdo Vindolanda; since the 1990s, excavators at Xuanquan, a Han military post office, have found twenty-three thousand undelivered letters, painted on bamboo strips between 111

B.C.

and

A.D.

107 (many of them complaints about how unreliable the mail was).

First-century-

A.D.

emperors could see perfectly well that war did not pay the way it used to, but they could not see that the very success of productive war had transformed the larger environment in which it operated. To be fair to them, it is always hard to know when to stop. “If we remember how many factors contribute to the balance of forces,” Clausewitz mused, “we will understand how difficult it is in some cases to determine which side has the upper hand.” Over the next few centuries, however, it would become all too clear who had it.

War Horse

The ancient empires reachedâand passedâtheir culminating points because by the first century

A.D.

, productive war had entangled them with the horsemen of the steppes. This was a long, drawn-out process, which made it all the harder for emperors to identify what was going on. We saw in

Chapter 2

that the entanglements began as early as 850

B.C.

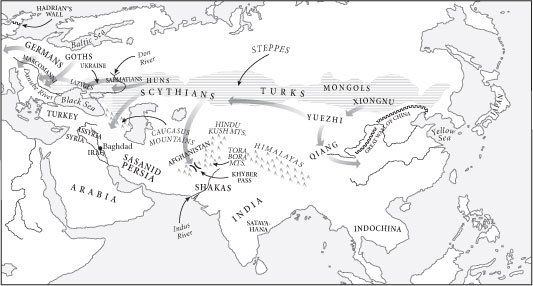

, when the Assyrian Empire began buying the big new horsesâstrong enough to carry riders on their backsâthat herders on the grasslands had succeeded in breeding. Over the centuries that followed, the empires kept expanding. Their farmers plowed up the edges of the steppes to grow grains, and their traders pushed deeper into central Asia to buy animals; and as they did so, the nomads along the ecological frontier where arid grasslands blurred into cultivated fields learned that they had new options. Often, they found, they could do better by selling horses to imperial agents than by rushing from oasis to oasis to fight other horsemen for a few mouthfuls of muddy water. Better still, they learned, when the imperialists would not pay the price they demanded, they could shoot their way into the empires and take what they wanted from the unarmed, peaceful peasants.

We first hear about an empire having trouble with steppe nomads in Assyrian sources before 700

B.C.

Assyria had expanded into the Caucasus Mountains, right at the edge of the steppes (

Figure 3.3

). When Scythian riders began terrorizing the borderlands, Assyrian kings simply hired some nomads to fight the other nomads for them. They quickly found, though, that the skills that made Scythians attractive employeesâmobility and ferocityâalso made them uncontrollable. The seeds of disaster were being planted.

Figure 3.3. Storms on the steppes: a millennium of asymmetric wars, ca. 700

B.C.

â

A.D.

300