War: What is it good for? (30 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Europeâat least when it came to gunneryâhad more in common with southern than with northern China. It was full of forts, had plenty of broken landscapes that constrained armies' movements, and, because it was so far from the steppes (which made cavalry expensive), its armies always included a lot of slow-moving infantry. In this environment, tinkering with guns to squeeze out small improvements made a great deal of sense, and by 1600 so many improvements had accumulated that European armies were becoming the best on earth.

If Ming dynasty emperors had had a crystal ball and could have seen that by the seventeenth century firearms would be effective enough to defeat nomad cavalry, they would surely have taken the long-term view and

made the investments to come up with corned powder, muskets, and wrought-iron cannons. But in the real world, no one can foresee the future (hard though some of us try). All we can do is respond to the immediate challenges that face us. Europeans invested in guns because it made sense at the time; Chinese did not invest in guns, because it did not make sense at the time; and because of all this good sense, Europe (almost) conquered the world.

Payback

Europeans had learned about guns in the fourteenth century because travelers, traders, and fighters had carried them westward across Eurasia, and in the sixteenth century Asians learned about improved European guns because travelers, traders, and fighters carried them back east again. It was payback, of a kind.

The Ottomans, who straddled the boundary between Europe and Asia, learned about European guns first. Turkish firepower usually lagged behind European but did stay decades ahead of gunnery in lands farther east and south. It was artillery mounted on wagons that slaughtered Persia's finest horsemen at Chaldiran in 1514 and Egypt's at Marj Dabiq two years later, giving the Ottomans mastery of the Middle East.

A generation later, Muscovyâanother state straddling the boundary between Europe and Asiaâalso learned to apply Western guns. Since the thirteenth century, Russians had been buying survival with annual bribes to the Mongols, but in the sixteenth Tsar Ivan the Terrible took revenge. Russians had learned the basics of gunnery in bloody wars against Sweden and Poland, and Ivan swept down the Volga River, using artillery to smash Mongol stockades in his way. By his death in 1584 he had doubled the size of Moscow's empire, but this was just the beginning. In 1598, Russian fur trappers armed with newfangled muskets crossed the Ural Mountains; by 1639, they were gazing on the Pacific Ocean.

Other things being equal, caravans would presumably have carried advanced European guns east along the Silk Roads all the way to China, but they were overtaken by the second great invention of this ageâthe oceangoing ship.

As in the case of guns, the basic technology was pioneered in Asia but perfected in Europe. Magnetic compasses, for instance, were in Chinese skippers' hands by 1119. Picked up by Arab merchants on the Indian Ocean, they reached Italians in the Mediterranean by 1180. Over the next three

centuries, East Asian shipwrights made further breakthroughs in rigging, steering, and hull construction. By 1403, China had the world's first dry docks, housing the biggest sailing ships ever built. Packed with watertight compartments, sealed with waterproof paint, and supported by freshwater tankers, these ships could have gone anywhere Chinese sailors wanted, and between 1405 and 1433 the famous admiral Zheng He led hundreds of them, manned by tens of thousands of sailors, to East Africa, Mecca, and Java.

Compared with this, Western ships looked very rough-and-ready, butâas with gunsâEuropeans took Asian ideas in radically different directions. Once again, the driving force was very basic: Europe's geography presented different challenges from Asia's, and in trying to rise to them, Europeans found enormous advantages in their relative backwardness.

Western Europe looked like the worst-placed part of Eurasia's lucky latitudes in the fifteenth centuryâjust “a distant marginal peninsula,” one economist has called it, far from the real centers of action in South and East Asia. European merchants were acutely conscious of the riches of China and India and for centuries had been seeking easy routes to the booming markets of the Orient. If anything, though, the situation seemed to be getting worse after 1400. The Mongol kingdoms were disintegrating, making the Silk Roads across the steppes more dangerous, while tolls imposed by the Ottomans had made the alternative route (overland from Syria to the Persian Gulf) more expensive. The best solution seemed to be to get to Asia by sailing around the bottom of Africa, bypassing the intervening kingdoms, but no one knew if that was even possible.

No part of Europe was better placed to find out than Portugal, and in the years after the capture of Ceuta, Portuguese ships nosed their way down Africa's west coast. It was hard going; oar-powered galleys ruled the roost in the Mediterranean but were ill suited to the distances and winds on the Atlantic. So serious did this seem that Prince Henry, one of the conquerors of Ceuta and third in line to the Portuguese throne, took personal charge of the push to produce better ships.

The project quickly paid off, in the form of caravels. These tiny ships, typically just fifty to a hundred feet long and displacing barely fifty tons, would have looked ridiculous to Zheng He, but they did the job. Their shallow bottoms could get into silty African river mouths, their square sails made them fast, and their lateen sails made them nimble. In 1420, Portuguese ships discovered Madeira and in 1427 the Azores; within a few years these islands were filled with flourishing plantations. In 1444 sailors

reached the Senegal River, giving them access to gold from African mines. In 1473 they crossed the equator, and in 1482 they arrived at the mouth of the mighty Congo (

Figure 4.4

).

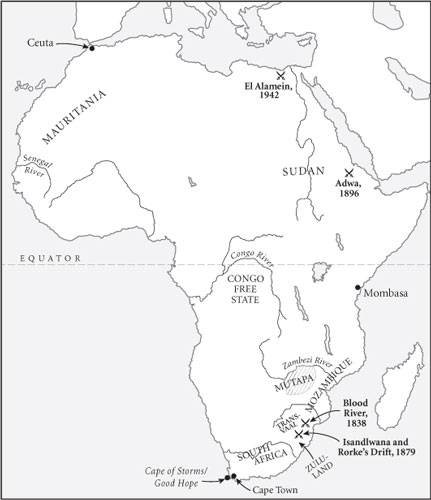

Figure 4.4. Locations in Africa mentioned in this chapter

Everything was going famously, but once past the Congo, caravels (and newer, bigger versions called carracks) found themselves facing strong headwinds. Progress stalled, until Europe's sailorsâafraid of nothingâfound two solutions. First, in 1487, Bartolomeu Dias hit on the dramatic idea of

volta do mar,

“returning by sea.” This meant plunging into the uncharted Atlantic in the hope of catching winds that would catapult him past the

bottom of Africa. Triumphant, he rounded what we now call the Cape of Good Hope. Dias, however, called it the Cape of Storms (the experience of trying to sleep through some of its howling gales makes me think Dias's name was the right one), but whatever we call the cape, the Portuguese sailors mutinied rather than go on in such foul weather. It was left to Vasco da Gama, in 1498, to take a second expedition around the bottom of Africa and into the Indian Ocean.

The second solution, Christopher Columbus's, was even more drastic. Like all educated Europeans, Columbus knew that the earth was round and thatâin theoryâby sailing west from Portugal, he would eventually get to the East. Most educated Europeans also knew that the world was about twenty-four thousand miles around, which meant that this route to the Indies was too long to be profitable. Columbus, however, refused to accept this, insisting that three thousand miles of sailing would get him to Japan. In 1492 he finally raised funds to prove his point.

Columbus went to his grave believing he had sailed to the land of the great khan, but it gradually became clear that his accidental discovery of a new world was more exciting. There was serious money to be made from shipping America's wealthâgold, silver, tobacco, even chocolateâback to Europe and shipping Africans to America to produce these fine things. European mariners transformed the Atlantic from a barrier into a highway.

It was a dangerous highway, though. Like the Mediterranean before the Roman conquest or the steppes before the Mongols, the Atlantic was largely beyond Leviathan's laws. Once a ship was out of sight of Cádiz or Lisbon, anything went. Anyone with a small ship, a couple of cannons, and no scruples could help himself (or occasionally herself) to the plunder of continents. The golden age of pirates had begun.

The sixteenth century's global war on piracy, fought everywhere from the Caribbean to the Taiwan Strait, was yet another asymmetric struggle. Leviathans could always win if they wanted to, but the take, hold, and build strategy that Pompey the Great had invented in the Mediterranean in the first century

B.C.

cost money. On the whole, governments calculated, putting up with pirates cost less than making war on them, so why bother? Clever bureaucrats could even turn piracy to their own ends, extracting bribes for turning a blind eye or even appointing the cutthroats as “privateers,” legally entitled to rob other countries' ships. A few unwary voyagers might have to walk the plank, but that seemed a small price to pay.

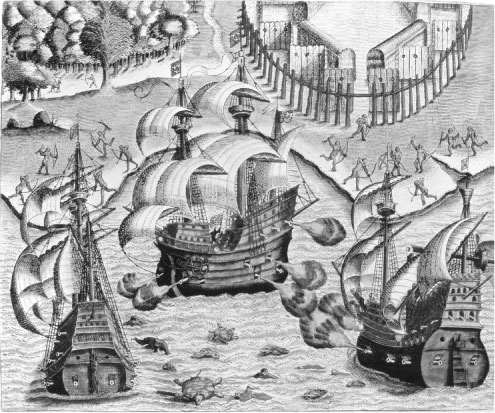

The voyagers, however, thought this was a very high price, and so they did the obvious thing: they armed their ships. Caravels and carracks could carry a few cannons, but by 1530 Portuguese shipbuilders were producing a new type, the galleon, which was basically a floating firing platform (

Figure 4.5

). The galleon's long and narrow hull, four masts, and small fore- and aftercastles made it fast, but the real gain came from lining its sides with cannons, blasting away from gunports cut in the hull just above the waterline, hurling eight-pound iron balls five hundred yards.

Figure 4.5. Floating firing platforms: French and Portuguese galleons engage off the coast of Brazil, probably in 1562.

For two thousand years, captains had fought by closing, ramming, and boarding, but now they learned to draw alongside and pour shot into the enemy through curtains of acrid smoke. There was still plenty of work for cutlass and dagger, but now men were more likely to be killed by “splinters”âan innocuous-sounding word for jagged, foot-long shards of oak that sprayed in every direction, tearing off arms and heads, whenever a cannonball ripped through a hull. One witness to the carnage spoke of

decks “much dyed in blood, their masts and tackle being moiled with brains, hair, pieces of skulls.”

Guns did not just hold pirates at bay, though. They also became a source of profit in their own right, because Asians would pay well for these vicious weapons. Several of da Gama's men jumped ship and set up as gunmakers to the sultan of Calicut, selling him four hundred cannons within a year. In 1521 the first Portuguese to reach China were also casting guns for local markets, and by 1524 Chinese craftsmen were making their own versions and corning powder.

The extreme case was Japan. When a storm blew three Portuguese ashore in 1542, they promptly sold their state-of-the-art muskets to a local lord and taught his metalworkers how to make more. By the 1560s Japanese guns were as sophisticated as anything in Europe and equally effective at making traditional fortifications obsolete. By contrast with Europe, though, defense did not run as quickly as offense in Japan, perhaps because advanced guns had appeared so suddenly rather than evolving over two centuries as in Europe. But whatever the cause, as we saw in

Chapter 3

, a single government controlled the whole archipelago by the 1580s.

European-style guns were such a hit that Asia's military men soon called all modern firearms by the generic label “Frankish” (

farangi

in Persia,

firingi

in India,

folangji

in China). They also adopted European tactics, learning that wagons bristling with modern muskets and cannons could actually defeat steppe horsemen.

Prince Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur's experience was typical. Fighting with bows and spears, his Afghan followers failed to hold Samarkand and Kabul when Uzbek horsemen attacked between 1501 and 1511, and he had to flee to India. Once there, Babur hired Ottoman advisers, who urged him to buy guns and wagons, and in 1526 he regained everything in the shattering victory of Panipat. The Mughal Empire that he founded would become the biggest in India's history.

Chinese soldiers seem to have discovered the wagon laager independently. “Wagons,” the commander of Beijing's defenses observed in the 1570s, “can serve as the walls of a camp; they can take the place of armor. When enemy cavalry swarms around, it has no way to pressure them; they are truly like walls with feet or horses without [need for] fodder. Still, everything depends on the firearms. If the firearms are lost, how can the wagons stand?”