War: What is it good for? (41 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Figure 5.4. Unhappy lot: the decline of the globocop's naval power relative to Germany, Japan, and the United States, 1880â1914

If Britain was the world's policeman, we might think of the new industrial giants as being rather like urban gangs. The globocop, like any cop, had to decide whether to confront these rivals, cut deals with them, or do some combination of the two. Britain could wage trade wars on its rivals, wage shooting wars on them, or make concessions. The first two options threatened to ruin the free trade that made Britain rich; the third, to strengthen the rivals so much that Britain would no longer be able to play globocop.

Matters came to a head first with the United States. The 1823 Monroe Doctrine had in theory banned European meddling in American waters, but in the 1860s the prospect of the Royal Navy intervening in the Civil War remained Abraham Lincoln's worst nightmare. By the 1890s, though, it was clear to all that Britain was no longer strong enough to project power into the western Atlantic while also meeting its other obligations. Facing facts, London initiated a “great rapprochement” with Washington. The globocop effectively took on a deputy, giving it its own beat.

Britain retreated even further in eastern waters. Japan was the only non-Western country that had succeeded in responding to the European onslaught by industrializing itself, and in the 1890s it was without doubt the greatest power in northeast Asia. Its fleet was not yet one of the world's top half-dozen, but given the distance separating Britain from the western Pacific, London concluded in 1902 that the only way to maintain some influence on the far side of the globe was a formal naval agreement, the first in Britain's history, with Japan.

Exactly a hundred years later, the U.S. defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld would tell journalists, “There are known unknowns, that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know; but there are also unknown unknownsâthe ones we don't know we don't know.” So long as the nineteenth century had a single, stable globocop, strategic problems were mostly

known unknowns. When the Russians threatened Constantinople in 1853, or the Indians mutinied in 1857, or the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, they did not know what the globocop would do to protect the world-system, but they did know it would do something. By the 1870s, however, unknown unknowns were multiplying. It became harder to predict whether the globocop would do anything at all. Uncertainty increased, and few could foresee the consequences of their actions. British strategists knew this, but given the grim alternatives, they kept taking on deputies. Their next deal, an entente cordiale agreed on in 1904, entrusted the Mediterranean to France so that Britain could concentrate on the biggest unknown unknown of all: Germany.

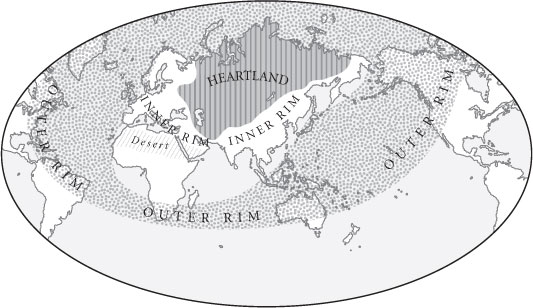

What made Germany so unknowable was its geography. In the same year that Britain cut its deal with France, Halford Mackinderâgeographer, explorer, and the first director of the London School of Economicsâgave an extraordinary public lecture. Twentieth-century history, he announced, would be driven by the balance between three vast regions. At the center of the story was what he called the heartlandâ“the pivot region of the world's politics, that vast area of Euro-Asia which is inaccessible to ships, but in antiquity lay open to the horse-riding nomads” (

Figure 5.5

).

Figure 5.5. Mackinder's map: the heartland, inner rim, and outer rim

Until the fifteenth century, Mackinder explained, raiders from the steppe heartland had dominated the rich civilizations of China, India, the Middle East, and Europe, which he called the inner rim. Beyond this inner rim, he also identified an outer rim, which counted for littleâuntil, after 1500, European ships drew this huge region together. By the eighteenth century, outer-rim powers were projecting force into the inner rim, contesting the heartland's control of it, and in the nineteenth the outer rim's strength was so great that it penetrated into the heartland itself (British troops were marching into Tibet even as Mackinder delivered his lecture). Control of the outer rim's seas delivered domination of both the inner rim and the heartlandâand therefore the world.

British politicians did not like sharing the outer rim with the United States, Japan, and France, but they gambled that they could strike deals with like-minded men who faced outer-rim problems much like Britain's own. Germany, though, was a different matter. It belonged to the inner rim, which gave it direct access to the heartland. Seen from London, a strong, united, industrialized Germany looked like the kind of place that might turn the heartland's resources against the outer rim. “If Germany were to ally herself with Russia,” Mackinder worried, it “would permit of the

use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would then be in sight.”

Seen from St. Petersburg, however, the other side of the same coin seemed more urgentâthe danger that Germany might get the upper hand against France and Britain and then turn the outer rim's resources against the heartland. The real risk was not of Germany's allying with Russia; it was of Germany's conquering Russia. Napoleon had tried this, but reaching all the way from the outer rim to Moscow had been too much for him. Germany, however, might find the reach from the inner rim more manageable.

Politicians in Berlin saw a third dimension. To them, the big danger was not that Germany would exploit the outer rim or the heartland; it was that the outer rim and the heartland would combine to crush Germany between them, which had almost happened several times since the eighteenth century. That, German leaders concluded, had to be prevented at all costs, and this simple strategic fact largely explains twentieth-century Germany's tragic history.

The three visions of where Germany fit into the world pointed toward very different ways of arranging European politics, but initially the Germans had things their own way. They owed much of this success to Otto von Bismarck, arguably the least scrupulous but most clear-sighted diplomat of the nineteenth century. Bismarck saw that Germans needed to be

violent in the 1860s. Short, sharp wars against Denmark, Austria, and France turned the muddle of weak German principalities into the strongest national state in the inner rim. But having won these wars, Bismarck saw that in the 1870s Germans needed to renounce violence. The best way to escape being squeezed between the heartland and the outer rim was to keep everyone else off balance, which meant making and breaking alliances in eastern and central Europe, placating Britain, and isolating France.

Bismarck kept all these balls in the air into the 1880s, but the proliferation of unknown unknowns as Britain's position deteriorated made such subtle juggling increasingly difficult. In 1890 a young new kaiser fired his aged chancellor and began wonderingâas did heads of state everywhereâwhether force might not, after all, be the best solution to the problems his nation faced in this uncertain world. He ordered his generals to plan preemptive wars, just in case, and German politicians played on the risk of war to distract voters' attention from the class conflicts at home caused by rapid industrialization. Bosses and workers might hate each other, but so long as both hated foreigners more, all might yet be well.

Germany's leaders found themselves taking chances that would have seemed insane in Bismarck's day, because the alternatives looked worse. Grabbing African colonies and building battleships were bound to provoke Britain, but not grabbing and building appeared to be the path to encirclement. At best, that might mean Germany's rivals could shut it out of overseas markets; at worst, it might mean war on two fronts. Germany had to do everything it could to break the circle, and yet everything it did just seemed to push its enemies closer together. With unknown unknowns multiplying and rumors of war weighing on all minds, continental powers bought more weapons, conscripted more of their young men, and kept them under arms longerâeven though that threatened to turn the rumors into reality.

By 1912 the kaiser and his advisers felt that drastic measures were the only options left. Sometimes they talked about forging a United States of Europe, dominated of course by Germany; at other times, as a Viennese newspaper put it on Christmas Day 1913, they envisioned “a central European customs union that the western states would sooner or later join, like it or not. This would create an economic union that would be equal, or perhaps even superior, to America.” In London or Washington, this sounded like fighting talk.

None of this made war inevitable in 1914. Franz Ferdinand could easily

have survived June 28; calmer heads could easily have prevailed in the weeks that followed. Most people, in fact, thought calmer heads

had

prevailed: investors in the bond markets showed little anxiety until late July, and politicians and generals went ahead with their summer vacations. With just slightly better luck, the abiding memory of 1914 would have been its fine weather, not its killing fields.

But what would have happened then? Avoiding war in 1914 would not have revived the globocop, because the continuing spread of industrial revolutions around the worldâcaused by the globocop's successâwould have made its position steadily less tenable. Unknown unknowns would have kept on multiplying. New crises would have followed the crisis of 1914, just as the Balkan crisis of 1914 had itself followed Moroccan crises in 1905 and 1911 and another Balkan crisis in 1912â13. Had every diplomat in twentieth-century Europe been a Bismarck born again, perhaps they could have carried on defusing emergencies indefinitely, but this was the real world, and its diplomats were, on average, no better and no worse than those of earlier ages. Every crisis was in effect a roll of the dice, and sooner or laterâif not in the 1910s, then surely in the 1920sâsome king or minister was going to conclude that war was, after all, the least bad solution to whatever problems were pressing on him.

And so, a month after Princip shot Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia, banking on the kaiser's assurance that he had “considered the question of Russian intervention and accepted the risk of a general war.” After all, the German chancellor mused, the alternative was “self-castration.” A week later most of Europe was on the march. There was no slithering over brinks, no planets spinning from their orbits; it was just a world in which the globocop had lost its grip.

The Storm Breaks

“The general aim of the war,” said a document drafted for the German chancellor a month into the fighting, “is security for the German Reich in west and east for all imaginable time.” To achieve that, “France must be so weakened as to make her revival as a great power impossible for all time [and] Russia must be thrust back as far as possible from Germany's eastern frontier and her domination over the non-Russian vassal peoples broken.” Annexations would follow in Belgium and France, former Russian provinces would become German satellites, and British goods would be shut out of French markets. The goal was a counterproductive war,

breaking the larger alliance that encircled Germany and dealing the globocop a terribleâperhaps fatalâblow.

Whether Germany went to war with this plan in mind or only formulated it in reaction to the terrible casualties of the first few weeks of fighting remains unclear, but either way the Germans were taking gigantic, terrifying risks. Bismarck's worst-case scenario came to pass in 1914, exposing Germany to the full weight of the heartland and the outer rim, and the German General Staff concluded that their one hope was to exploit their central position and industrial organization to knock France out of the war before Russia could mobilize.

Pulling off an administrative masterstroke, German bureaucrats commandeered eight thousand trains and rushed 1.6 million men and half a million horses to the western frontier. From there they swept through neutral Belgium, marching and fighting without rest. By September 7, the vanguard was across the Marne River, just twenty miles from Paris. On the map, it looked as if the war were almost won, with the French army being enveloped and forced away from its capital, but Helmuth von Moltke, the German chief of staff, was about to discover how modern warfare really worked. His twentieth-century Leviathan had called up a million-man army, which was now spread across a hundred miles, but he only had nineteenth-century ways of communicating with it. Radios were rare and unreliable, telephones were worse, and there were virtually no spotter planes.