Warrior Pose (17 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

With Tom Brokaw, Kuwait City, Kuwait, 1991.

“Where are your wounded Kuwaitis?” I ask the doctor who has allowed me in.

“There are none,” he answers matter-of-factly. “If they are here, they are dead.”

“Where?” I say.

“In the basement morgue.”

“Please take me there.”

“You do not want to see this.”

“Yes, we must. Please. Let's go there now, doctor.”

The stench in the morgue is tremendous. We have to wear hospital masks over our noses and mouths, and it barely cuts the acrid odor. Bodies are piled everywhere, heaped on top of one another. I see dead men with horrid facial wounds. Tongues cut out. Acid poured over their faces. Eyes gouged out. Some have been castrated. Others have multiple gunshot and stab wounds. The bodies of young girls show signs of violent rape, some with iron construction rods, called rebar, forced into their body cavities. I am overwhelmed with grief. What dark evil dwells within us that could ever prompt such atrocities?

None of the horrors in this morgue can be broadcast, but we film anyway so there is a record of this savagery. It's likely the Iraqi soldiers lying comfortably in their hospital beds three flights above me took part in some of this grotesque torture. I feel a surge of rage. Part of me wants to find a weapon, burst in, and shoot them dead. Then I realize my response would be a mild version of the same madness that drove them to commit such horrible acts of cruelty.

“Doesn't it outrage you, treating those Iraqi soldiers in your trauma ward?” I ask the Kuwaiti doctor as we depart the hellish morgue.

“It is my oath as a physician,” he says calmly. “I am here to save lives, whomever they might be.”

It's an extraordinary expression of compassion in the face of demonic human behavior. I've met many heroes while covering this war, but this is a man whose courage, integrity, and compassion I will never forget.

CHAPTER 10

The Gulf War Aftermath: Kurdistan

T

HE PAIN. It always gets worse when I'm exhausted. Tonight, at the end of another long day, a sharp, electric sensation shoots down the back of my left leg, spiking into my heel bone. This has been happening more frequently lately. It feels like a tripwire from a grenade is lodged in my lower back, ready to explode if I make the wrong move. I take a few extra pain pills and slip into my sleeping bag on the bed of my sacked hotel room across from the American Embassy in Kuwait. As has become my nightly routine, I whisper to myself that the pain will be gone for good in the morning.

It has to go away. It just has to.

This is my fifth day in Kuwait City. The Iraqi Army has proven to be no match for the Allied Forces led by the Americans, and has fled home in disgrace. Operation Desert Storm is over. Kuwait has been liberated. But there's hardly time to breathe as a new crisis begins to unfold in the northern provinces of Iraq.

The region is known as Kurdistan: a rugged, mountainous territory spanning a wide area where the borders of Iraq, Turkey, Iran, and Syria converge. The Iraqi Kurds, some 4 million strong, have sought independence for more than a century. Their armed fighters are known as

peshmerga

, which literally means “those who face death.” And face death they have, suffering massacres and mass

casualties at the hands of Iraqi troops every time they have risen up for independence. Now emboldened by Saddam's defeat in Kuwait, a new uprising has begun.

Saddam's troops have swarmed into Kurdistan to crush the revolt, overrunning and pillaging village after village. It was just eight years ago that the Kurds suffered a similar fate when they sided with neighboring Iran during the IranâIraq War. Scores of villages were destroyed. Thousands were killed. And at the end of the war, in 1988, Saddam hit the Kurds with chemical weapons in a massacre known as Bloody Friday. It was this attack that convinced America that Saddam would use chemical weapons against U.S. forces in the Gulf War. Now, millions of Kurds are fleeing into the high mountain ranges along the Turkish-Iraqi frontier. Their maxim has long been, “Kurds have no friends but the mountains.” It's the only safe haven they have.

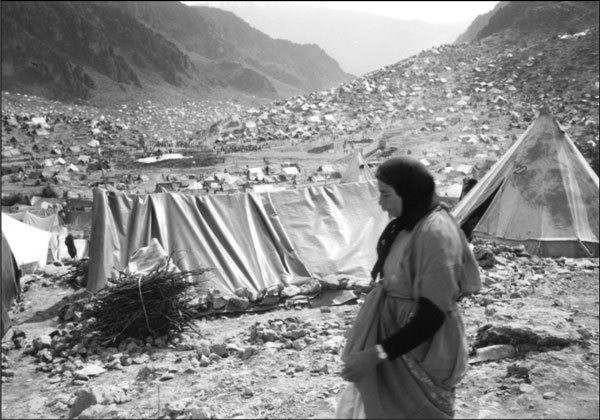

I've been posted to a base camp established for the media just across the border in southern Turkey, covering the Kurdish refugee crisis for NBC News. Periodically, U.S. Army helicopters lift us into the mountain refugee camps, banking down steep, sheer cliffs to avoid the possibility of Iraqi artillery fire. It's harsh terrain, far from friendly to the Kurds. Conditions in the camps are beyond dismal. Each family has put up a small tent for shelter. They only have what little food they could bring, mostly grain, and it is running out fast. Winter is yet to come, but the bitter cold is here. Merchants and artisans, farmers and traders, grandmothers and infants huddle together to keep warm, wondering if they'll ever see their villages again. The fear of Saddam and his brutal army is palpable, even visible in their terrified stares.

The camps are just above the timberline. Most of the available wood has been gathered and burned for cooking a traditional gruel, called

sawar

, made with crushed wheat grain. The

sawar

is running out, and the United States has begun airdropping Army rations, the MREs that stuck in my belly while I was a pool reporter with the Marines. These ancient people can't digest this food, and diarrhea abounds. There is no sanitation, and the Kurds often relieve themselves right in front of their tents. As a result, dehydration has begun claiming lives, and there are fears of a cholera outbreak. As so often happens in war, children are the first victims. Already, a few mothers with glazed eyes cling to cold, lifeless babies, refusing to acknowledge they have lost their infants.

Kurdish Refugee Camp, Northern Iraq, 1991.

A French medic from

Médecins Sans Frontières,

a renowned humanitarian organization that provides medical aid to victims of war, is with one young woman. She's holding her dead child in her arms as she wanders aimlessly through the camp. She appears to have no other family. Our best guess is that her husband was killed by the Iraqis. This fragile young mother, extremely thin from lack of nourishment, can't be more than sixteen years old. Her thick, matted auburn hair hangs down over her face like a mask but can't conceal her intense blue eyes, which are locked in an empty stare. Time feels as frozen as the sharp icicles hanging from tattered refugee tents.

Neither of us speaks her language, so we simply comfort her by wrapping a warm blanket around her shoulders.

We wait by the mother's side, hoping she will come to the realization that it's best to allow a burial. Finally, she begins to sob, almost imperceptibly, and slowly offers the child to the medic without ever making eye contact. He gently receives the bundle and walks softly toward the makeshift burial pit. The young mother stands like a statue, gazing at the ice-cold ground. It's a stark reminder that the pain eating away at my back right now is nothing for me to whine about.

In the valleys below the refugee camps, the same U.S. and British air forces that have been airlifting aid to the refugees have established a no-fly zone, promising to shoot down any Iraqi aircraft that violates this decree. They also have moved ground forces into Kurdistan that are pushing the Iraqi Army out of Kurdish cities and back toward Baghdad. It's delicate. Any direct conflict could trigger another allout war. The Pentagon calls it Operation Provide Comfort, and while journalists have been allowed to fly on Army helicopters into the mountain refugee camps, we've been denied access to this dangerous ground game.

After covering the refugee crisis, I manage to get ahold of an old camper van with a bed and stove that NBC has rented indefinitely. This becomes my living quarters at the media camp just across the Iraq border in Turkey. I need it. It's getting tougher to wriggle into a sleeping bag with a sore back, and the ground feels like it keeps getting harder. The camper bed, by contrast, feels luxurious. And the vehicle gives me some freedom of movement. We're not allowed to wander from the media camp without military permission, but I can't help myself. I want to cover the war, not just the refugee crisis. So I decide to make an attempt to cross the border secretly into Iraq.

When my Turkish cameraman and I drive the camper up to the Iraqi border checkpoint early the next morning, it's desolate and eerily quiet. Trash is strewn everywhere. There's no one in sight. We slow to a crawl, zigzagging around cement barricades that are posted

with Arabic signs warning that the border is closed. We warily move toward a group of inspection buildings that look abandoned. Just as we're about to cross, a lone Iraqi border guard in a tan uniform appears from a small guard stand.

“

Qef!

” He shouts the Arabic word for “stop” with menacing authority. The guard is in his fifties, tall and beefy. With his hair and moustache dyed black, he looks like an impersonator of Saddam Hussein. He is clearly a Sunni Muslim. The Sunnis and Shiites are factions of Islam. Sunnis form the minority in Iraq, but they hold power. This means they typically get the better jobs, run the government, and form the backbone of the military. I was hoping we would find a Kurdish guard, or maybe a Shiite who might be pleased that America just vanquished Saddam in Kuwait. But instead we're in a dicey situation.

Pointing his automatic rifle just above our heads, the guard aggressively waves us to a halt. I can't understand much beyond

qef

, but he's clearly asserting control and demanding to know what we're doing here. I slowly reach into my shirt pocket and carefully hand him a large wad of crumpled Turkish lira, offering a reasonable border crossing fee for these dangerous times, with a friendly smile, of course. He pauses, staring me hard in the eyes as if he'd rather shoot me than return my smile. Then he takes the money and sternly waves us through with his rifle. I punch the gas pedal and drive as fast as the old camper will go, just in case he changes his mind.

We soon arrive in Zakho, a normally bustling trading center that has become a ghost town. Zakho was once home to the ancient Catholic Diocese of Malta. It was also called “The Jerusalem of Kurdistan” before brutal campaigns against the Jewish population sent this small religious minority fleeing to Palestine in 1920. That left Zakho predominantly Kurdish, until now. It appears all 600,000 residents have fled into the mountains. We can't find a single soul as we film looted stores, empty homes, broken windowsâthe visible evidence of hasty exits and shattered lives.