Warrior Pose (21 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

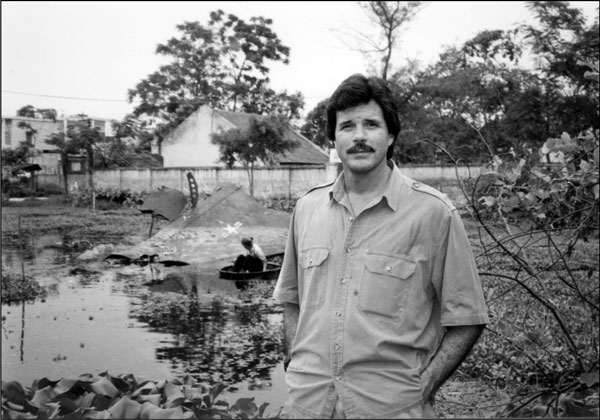

The following morning we find our way to Hun Tiep Lake, in a residential district just outside Hanoi proper. Sitting in the middle of the lake's murky water is the wreckage of an American B-52 bomber. Its nose and wings are submerged. A large, twisted piece of the fuselage pokes into the sky with a white Air Force star at its center. Its rusted landing gear sticks out to one side at the waterline. Nicknamed “Rose 1,” it was shot down during Christmas air raids on December 19, 1972. It's been two decades since the war ended, but the bomber looks like it just crashed.

During the Christmas raids, President Richard Nixon was negotiating to end the war, trying not to make it look like a complete surrender. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had just uttered the famous words, “Peace is at hand,” during negotiations with the North Vietnamese at a summit in Paris. Then came the surprise American bombing attack that shocked and outraged the world. It was called Operation Linebacker II, a football metaphor for eleven days of relentless aerial bombardment, the heaviest strikes launched by the Air Force since World War II. More than 1,600 civilians were killed in Hanoi and surrounding villages. Tens of thousands were wounded. In America, the pilots who flew the sorties some twenty years ago are still revered as heroes. Here, they're remembered as demons that came in the night and wreaked havoc. For the Vietnamese, this B-52 in Hun Tiep Lake is a monument to victory over a mighty and brutal foe.

My photographer and I are paddling out to the wreckage now in a small rowboat. The silence is only interrupted by the occasional croaking of small frogs sunning themselves on lily pads. An elderly Vietnamese woman in a woven straw hat is waist deep in the water, harvesting watercress. Her face is soft and serene despite deep lines of age. She could be anyone's loving grandmother. Her gentle, rhythmic movements send small, circular ripples lapping against the bomber's fuselage and give our boat a gentle rock. She pays us no mind, as if we do not exist. I try to imagine what it was like for her and her family on the nights the B-52s screamed overhead and the bombs rained down, shaking the earth with their thunder.

Hun Tiep Lake, Vietnam, 1992.

Each morning at dawn, I walk from my small hotel in the center of Hanoi to visit Hoan Kiem Lake and Turtle Tower, and then I slip into the Old Quarter. This helps work out the kinks in my back and I also get to immerse myself in the local culture. I'm always drawn to the places where the poorer people live. Their lives inevitably tell the story of a nation's past, how its leaders have treated their people,

and what the future might hold. Wandering the Old Quarter, I love the aromas of the outdoor markets drifting through the air and the wrinkled, smiling faces with missing teeth that reveal a history of quiet suffering and perseverance.

Even at this early hour, the quarter is bustling, yet it retains a sense of quietude and peace. Residents squat in the streets with rice bowls, silently enjoying breakfast. It's rare for an outsider to be here, especially a tall, white one. Even though I must be a sight, few look up or acknowledge my presence. For three days straight, however, I've made eye contact with a middle-aged man during my morning walks. Like most men here, he's clad in the traditional pajama-style black shirt and trousers. On this morning, he signals me to squat down and join him for a bowl of rice.

Although the United States fears the Soviets are meddling here, most Vietnamese loathe Russians and would never befriend one. They also dislike the U.S. government. But they like Americans. I don't speak any Vietnamese, so the only words I utter are, “

Je suis Américain

,” hoping he understands French from the colonial days.

“

Très bien,

” he answers with a wide grin.

This almost exhausts my French, so we communicate with open smiles, subtle body language, and simple gestures. As we eat steaming, gooey rice with our fingers, I remember Afghanistan, where the left hand is used after going to the toilet; thinking it might be the same here, I am careful to use my right hand for the rice. I feel privileged to sit in the street and enjoy this simple meal, and although it's only rice, it tastes sumptuous and far superior to the pricey, processed MREs I lived on during the Gulf War. As we finish, my friend floats up to standing with ease. It takes me a while to get up from being cross-legged on the ground for so long, and it's a struggle to do it without groaning.

Once I'm on my feet, he beckons me to follow him. We walk through a narrow, dusty shop filled with old wood and iron parts for repairing the hand-pulled street carts used to transport goods throughout the Old Quarter. A creaky door in the back of the dilapidated building leads to his home. There are at least three generations of his family

living in this tiny space, which is partitioned into miniature rooms by gray blankets tacked to the ceiling. His grandchildren, peeking from behind one old blanket, are wide-eyed. There must be at least a half dozen of them. They've never seen such a stranger, let alone one right here in their home.

My new friend guides me to a far corner. We step past his wife as she squats before a tiny hot plate on the floor, cooking more rice while paying us no mind. He pulls back a tapestry on the wall, revealing a door. It opens onto a narrow passageway, barely illuminated by oil lamps. For a moment, I wonder if I'm being set up to be robbed or roughed up, but I feel genuine kinship with this man. I follow him into the catacombs. The still, dank air smells a thousand years old.

We zig and zag as the hallway narrows. My shoulders brush the walls as my friend slides along effortlessly. My boots land with jarring thumps. My friend's footsteps are silent. A few sharp turns now. There are no more lamps. It's pitch black, except for a faint glow at the end of the corridor outlining another door. My friend slowly opens the door and light floods out from a small room brightly lit by hundreds of candles. Stepping inside, I see that the room is filled with beautiful Buddhist statues, artwork, and artifacts. Incense sweetens the air. Wax runs down the candleholders, forming layers of thick puddles on the rough wood floor. It is a humble temple, yet it feels holier than any great cathedral I have ever seen.

The French suppressed Buddhism in Vietnam when they colonized much of Indochina in the mid 1800s. It was further suppressed in the 1950s after Ho Chi Minh and his communist guerillas, known as the Vietminh, established a Democratic Republic of Vietnam in North Vietnam. I sense the candles in this temple have been kept lit throughout the years as a silent protest, secretly paying homage to the flame of an ancient spiritual tradition. My friend gazes into my eyes, brings his palms together at his heart, and gently bows toward me. I'm not sure what this means, but it feels like a great honor and I return the gesture with a soft smile of gratitude for being allowed to enter this sacred space. I'm mystified, however, why he brought me here.

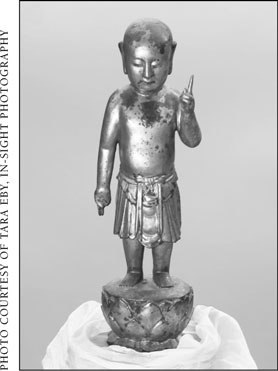

Golden Buddha

A gilded wooden statue of Buddha is the centerpiece of the temple altar. It's about a foot and a half tall. The Buddha is standing atop a beautifully carved lotus. The index finger of his left hand is pointing up, his right index finger is pointing down. I don't know what this gesture symbolizes, but the statue has an aura of wisdom and serenity. My friend steps over and gently lifts the golden Buddha from the altar. I watch spellbound as he wraps it in a beautiful piece of light brown silk cloth, turns toward me with a tender gaze, and offers it to me. I'm stunned. I resist at first, but he softly persists. He gestures to me to conceal it in my shoulder bag. I finally understandâat least I think I do. He wants the statue smuggled to freedom.

I wonder what will happen if it's discovered by the authorities during my departure from Hanoi. Will I create an incident? Be arrested and imprisoned for smuggling a spiritual artifact out of Vietnam at such a delicate time in history? I pull back a corner of the silk to reveal the Buddha's face. I swear he's looking at me as if to say, “Let's go!” I gently cover him up and carefully tuck him away in my bag, offering a gentle bow of my head to my new friend who gave me this precious gift.

Japan's Economic Bubble

Throughout the ages, all great spiritual texts have counseled against greed and self-indulgence. The Bible warns it's easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. The Bhagavad-Gita calls greed, anger, and lust “Doorways to Hell.” Buddhism warns that avarice and desire are afflictions that inevitably lead to suffering. Yet we never seem to listen or learn. Great empires perpetually overextend, over-consume, and overindulgeâand most eventually come crashing down.

Rising from the ashes of World War II, Japan's so-called economic miracle is the darling of the capitalist world. It's the early 1990s, and the economy is rocketing. Real estate prices have soared to astronomical levels. The Tokyo Stock Exchange is surpassing record levels. Credit is readily available to all, with interest rates at virtually zero. Speculation is rampant and hubris abounds. But now there are subtle signs and undercurrents indicating that the Japanese economy is in a huge bubble that is about to burst, yet everyone here is in denial and none will acknowledge it.

I'm hitting a wall as I try to report this. Government spokespersons, economists, and businessmen hold deep fears about the bubble, but won't go on the record with me. Corporations won't discuss downsizing or layoffs, especially in a nation where jobs are all but guaranteed for life. As a result of being isolated on an island throughout the millennia, Japan is a unique culture in Asia. Foreigners are kept as outsiders, tolerated and treated with respect but rarely trusted or allowed to fully integrate into the culture. Shintoism, the indigenous spiritual tradition here, is designed to sustain a present-day connection to the ancient past. Its rituals are complex, ornate, and arcane. Shinto includes an approach to life called

honne

and

tatemae. Honne

is true circumstances.

Tatemae

is the art of hiding the truth when revealing it would be embarrassing.

White-collar workers, called “salarymen,” form the new middle class, which traditionally consisted of farmers and shopkeepers. The salarymen endure long commutes and work horrendous hours for Japan's burgeoning corporations. It's a life of maximum stress, and as

a result they are notorious for their consumption of saké and beer. It's rare to see them, or any Japanese people, show emotion, because to do so is considered weak and undignified. Talking about one's troubles or being seen as a failure is called “losing face” and is taboo on both the personal and national levels.

The only hard evidence I have for this economic crisis is an interview with an American economic expert in Tokyo documenting increased layoffs, widespread psychological depression, and a growing rate of suicide. I've been pitching the story on the morning conference calls with 30 Rock for days. No takers, everyone wants more texture and some definitive proof, and all I get is

tatemae

. Finally, in a small article buried in a newspaper from Shizuoka Prefecture on the foothills of Mount Fuji, a tragic confirmation: A salaryman who lost his job walked up into the deep snows of the mountain with his wife and two young children. They never returned. They chose death rather than public humiliation and loss of face.