Warszawa II (6 page)

Authors: Norbert Bacyk

An excellent picture of a MG42 weighing approximately 12kgs. A burdensome weight if one was forced to bear it for a whole day! (Leandoer & Ekholm Archive)

A Soviet mortar of calibre 8.2 cm which was transported on a motor cycle, July 1944 somewhere in eastern Poland. (Leandoer & Ekholm Archive)

Zjukov knew that the Soviet summer offensive along the central sector of the eastern front would soon have to be slowed down. This was quite simply a requirement for implementing the masterly plan to launch the assault on not one, but rather several fronts, along with the incredible losses sustained in the fighting thus far. By the end of July, the Germans had already strengthened their positions in western Lithuania and across the Podlaski lowlands, and no reinforcements had subsequently arrived in the Baltic republics. Stalin demanded results on the front's flanks â but, for the moment, was primarily concerned with the situation to the south, where the large-scale offensive against Rumania was to begin in about three weeks time. Not even the powerful Soviet Army could handle two such broadly pursued and geographically divided strategic offensives simultaneously (the problem was not rooted in the number of soldiers available but in the system which controlled how the soldiers were deployed and how provisions and equipment were distributed.) It was with these circumstances in mind that Zjukov ordered Rokossovskij to first seize the well-defended bridge emplacements on the banks of the WisÅa and Narew Rivers. Konev also received a similar order. If the defenders resistance proved to be weak, both Marshals could press the attack further towards the Kraków â Åódź â ToruÅ line. But STAVKA, in fact, didn't really expect all that much. It was typical of headquarters to issue orders that were somewhat overstated. In February 1943 for example, an order was issued to the effect that the enemy was to be driven across the Dnieper (in reality, the Germans crossed the river for the first time in October), and in the Autumn of 1943, headquarters ordered that Riga should be occupied before the end of the year (Latvia's capital city was, in fact, taken in October ...1944).

Zjukov and the other officers at headquarters had another plan. For them, it was the bridge emplacements that were vital. After the success in the Balkans, it was around these strategic locations that they wanted to assemble the main Soviet combat strength and focus on a decisive offensive against Berlin. This concept originated in the summer of 1944 and became a reality by the winter of 1945. As it turned out, Warsaw played a subordinate role in the Soviet military plans. Gaining control of the city's Praga sector was viewed as a high priority objective that should be accomplished as soon as possible, which is to say, during the first week of August. It was quite obvious that the chances of gaining control over the bridge emplacements were nearly non-existent. The Germans had mined them, and the approach roads to the bridges were covered by 88 mm guns and machine-guns hidden in concrete bunkers. The Soviets had gotten this intelligence toward the end of July from its agents and air-reconnaissance. Storming city sectors west of the river with frontline troops using Praga as a jump-off location was completely dismissed for tactical reasons. All of those cities built around rivers, like Kiev and Budapest, were seized through outflanking manoeuvres this also proved to be the case at Warsaw when it finally fell in January of 1945. Zjukov intimated to Rokossovskij that the city would be captured from the bridge abutments south of the Polish capital. In which case, the 8th Guards Army would be able to carry it out.

Katyusha BM 13-16 launching rockets against the Germans in July 1944 in Eastern Poland. (Leandoer & Ekholm Archive)

The political question remained however, and it presented a particularly sticky problem. Stalin was concerned about the Home Army's troops in Warsaw, not from a military perspective but for propaganda reasons. Any attempt to disarm the Polish resistance movement in the capital city naturally threatened to awaken violent conflict to life. It appears â with respect to this matter, no documentation has been saved â as if the Soviet dictator awaited the outcome of the assault and was counting on a rapid seizure of Warsaw. The radio station “KoÅciuszko” which was controlled by the communists, encouraged the Uprising. This kind of appeal was standard Soviet operating procedure when a need was seen to dilute the ferment of concern in the resistance movement's backers. Fighting in the city would work to facilitate Soviet troop operations. In Warsaw, not only had the home-army remained combat ready, along with the organizations that co-operated with it, but also the so-called “People's-Army.” Much depended on the precise time point the Uprising took place.

Stalin must have known, with a fair degree of certainty, that the 2nd Tank Army which was due to attack Praga with only one tank corps (the other two were designated to cut off the German 2nd Army) would not be strong enough to seize Warsawâs central sectors west of the river. The regular infantry armies could carry this out. But these forces wouldn't arrive at the city until a couple of days later, and unless there was a state of total chaos on the German side or an uprising, nothing could guarantee a successful crossing of the WisÅa in an urban setting. What the Soviet dictator actually planned, we'll never know. Perhaps he had counted on the fighting breaking out in the city prematurely. His perception was that the Germans would pacify the city within a couple of days and destroy the Home Army, after which the 8th Guards Army could enter the Polish capital from the south. It's also possible, as has already been mentioned, that Stalin shelved decisions concerning Warsaw until later and, in effect, let them be decided based on what resulted from the frontline attacks east of Poland's capital.

German infantry under fire outside of Warsaw in July 1944. (Leandoer & Ekholm Archive)

Towards the end of July, military operations began to directly take in Praga's south-eastern suburbs. On July 27, brigades with frontline troops from the 2nd Tank Army began a series of debilitating battles over a 40km stretch and took possession of the Garowlin-area. At that moment, the German 9th Army's command of the approaches into Warsaw rested solely on General Fritz Frank's 73rd Infantry-Division (the 70th, 170th and 186th Infantry-Regiments, and Artillery-Regiment 173) along with smaller units drawn from General Wilhem Schmalz's division “Herman Göring” (Aufklärungs-Abteilung and a portion of Flak -Regiment). General von Vormann deployed, rashly enough, these weakened forces (Gruppe “Frank”) to the south with the mission of impeding the pace of the Soviet advance. In fighting with two Soviet tank corps over July 27-28, the 73rd Infantry-Division suffered heavy losses and was driven back to the Otwock â Minsk Mazowiecki line. General Frank was taken prisoner and a portion of the units from his division escaped in tatters to the other side of the WisÅa.

“If only there was time⦔

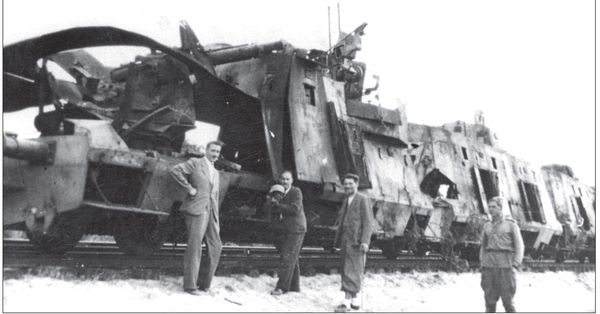

The destroyed German armoured train no. 74, in the Otwock-region, July 194

A mounted reconnaissance patrol from an infantry unit, one early morning outside Warsaw, July 1944.