Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering (42 page)

Read Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering Online

Authors: John W. Dower

21

. Although Kurosawa recalls

The Most Beautiful

with affection in his memoirs, as of 2004 it had fallen under the tacit censorship that still governs propagandistic treatments from Japan's war years. Unlike his many other films, it still had not been made commercially available with English subtitles.

The contrast between Japanese and Hollywood films extends to animated cartoons. The American cartoons involved slapstick mayhem against generic short, buck-toothed, slant-eyed figures who wore hornrim glasses and kept saying things like “So solly.” The “Popeye” cartoons were a perfect expression of this, as their titles alone suggest (“Scrap the Japs,” “You're a Sap, Mister Jap”). Looney Tunes propagated the stereotype of buck-toothed idiots in a series titled

Tokio Jokio

. The wittiest rendering of these cartoon clichés was

Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips

. By contrast, the major Japanese animationâwhich did not appear until near the end of the warâwas a long, innovative treatment that wedded Japanese folklore and children's culture (the story of “Momotar

Å

,” the Peach Boy) to long-ago history (inserted as a shadow-play account of the European conquest of a peaceful Southeast Asian kingdom). The film placed all this in the imagined rendering of Japanese paratroopers capturing a British stronghold in the South Seas and forcing its absurd and craven officers (who had demonic horns on their heads) to agree to unconditional surrender. The enemy officers actually spoke British Englishâwith subtitles in Japanese that made it clear that adults were a major part of the intended audience. Titled

Momotar

Å

to Umi no Shinpei

(Momotar

Å

and the Divine Troops of the Ocean), this was propaganda with a vengeanceâbut also with levels of artistic finesse and conceptual complexity very different from the poke-in-the-eye jocularity of Popeye and Bugs Bunny. The “Momotar

Å

paradigm” is discussed in Dower,

War Without Mercy

, 251â57.

22

. Before the confiscated Japanese paintings were returned to Japan, they were copied for reproduction in an elaborate but little-known U.S. government publication: see

Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, vol. 2, pts. I and II

(1966); these two volumes include scores of glossy reproductions. The major compilation of these paintings appeared shortly after their return to Japan in

Taiheiy

Å

sens

Å

meigash

Å«

(Nobelsha, 1967). This carries the English title

The Pacific War Art Collection

and romanizes artists' names and translates picture titles in the captions. There are one hundred plates in this large-format volume, which remains the major source for accessing this remarkable artwork.

WAR AND MEMORY IN JAPAN

1

. Watanabe Kazuo,

Haisen Nikki

(Diary of defeat), ed. Kushida Magoichi and Ninomiya Atsushi (Hakubunkan Shinsha, 1995), 36â38,

56â58, 77. The passage in question appeared in Romain Rolland's

Au-dessus de la melée

, and the original German phrase that Rolland quoted and Watanabe rendered as “aptitude for being unloved” (

aisarenu n

Å

ryoku; aisarenai n

Å

ryoku

) was

Unbeliebtheit

. The 1946 essay is reprinted in ibid., 43â48. In 1970, Watanabe added a very brief “postscript” to this essay expressing concern that Japanese pride in emerging as an industrial power was but one more reflection of the superficiality that caused his compatriots to be so unloved.

2

. By “Germany,” I refer primarily to the former “West Germany” here.

3

. High Japanese government officials have in fact made numerous public statements of “regret” and “apology” concerning imperial Japan's acts of colonialism (especially in Korea) and belligerency and atrocity in World War II. Some of these statements have been quite forthright, but few have attracted widespread media attention outside of Japan. None has been praised for being a statesman-like,

emblematic

utterance comparable to the famous speech delivered by Germany's former president Richard von Weizsacker on May 8, 1985, the fortieth anniversary of Germany's surrender. It is noteworthy, and hardly a coincidence, that the two most unequivocal statements acknowledging Japan's war responsibility were delivered by prime ministers who headed short-lived coalition cabinets and were not affiliated with the Liberal Democratic Party: Hosokawa Morihiro in 1993 and Murayama Tomiichi on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war in 1995. For a detailed critical summary of official Japanese statements on the war, see Wakamiya Yoshibumi,

The Postwar Conservative View of Asia: How the Political Right Has Delayed Japan's Coming to Terms with Its History of Aggression in Asia

(LICB International Library Foundation, 1998). Wakamiya is an editor at the

Asahi Shimbun

newspaper, and this volume is a translation of his 1995 book

Sengo Hoshu no Ajia Kan

. Ian Buruma offers a comparative study of German and Japanese recollections of the war in

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994). See also Thomas U. Berger,

Cultures of Antimilitarism: National Security in Germany and Japan

(The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998). For a comparative study focusing on textbooks, see Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds.,

Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany, and the United States

(M.E. Sharpe, 2000). The issue of massaging official statements of apology for the war so as not to besmirch

the memory of Japan's own war dead emerged vividly in 1995, when the Diet debated (and watered down) a formal statement on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war. For a selection of translated documents from this debate, see John W. Dower, “Japan Addresses Its War Responsibility,”

ii: The Journal of the International Institute

(newsletter of the International Institute, University of Michigan) 3, no. 1 (Autumn 1995): 8â11.

4

. Mori was forced to step down as party head and prime minister in April 2001, after merely a year in office. The manner in which his “land of the gods” comment triggered a critical public debate on national identity is exemplified by a series of guest essays initiated in August 2000 in the influential daily newspaper

Asahi Shimbun

under the topical title “Land of the Gods, Land of the People” (

Kami no Kuni, Hito no Kuni

). The general thrust of the series was to demonstrate in detail how reactionary and anachronistic Mori's rhetoric was. At the same time, however, non-Japaneseâand Americans in particularâshould keep in mind how

typical

Mori's rhetoric is of conservative nationalism in general. To give but one recent example, in the U.S. presidential campaign of 2000, the Democratic vice-presidential candidate called the United States “the most religious country in the world” and spoke of all Americans as being “children of the same awesome God,” while the Republican presidential candidate was proclaiming that “Our nation is chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world of justice and inclusion and diversity without division” (

New York Times

, August 29, 2000).

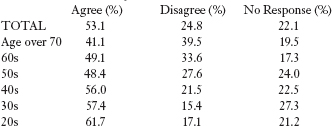

5

. The

Yomiuri

poll, based on a random sample of 3,000 individuals, was published on October 5, 1993, and is reproduced in the October 1993 issue of the Japanese government publication

Japan Views

(10). The full poll results are as follows:

WAS JAPAN AN “AGGRESSOR”?

6

. The “Carthage” quote appears in an essay by Namikawa Eita in Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform,

The Restoration of a National History: Why Was the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform Established, and What Are Its Goals

? (Tokyo, 1998), 15. This pamphlet, published in English, was widely distributed among English-speaking Japan specialists. The society (whose slightly differently named Japanese parent group is the Atarashii Rekishi Ky

Å

kasho o Tsukuru Kai) is one of two influential organizations founded in the mid-1990s by Fujioka Nobukatsu, a professor of education at the University of Tokyo. The other organization is the misleadingly named Liberal View of History Study Group (Jiy

Å«

shugi Shikan Kenky

Å«

kai). Numerous books and countless articles have been promoted by these organizations, including a huge (775 pages) new “History of the Japanese People” (

Kokumin no Rekishi

) written by Professor Nishio Kanji (a specialist in German literature at Electro-Communications University), and published in 1999 by Sankei Shimbunsha (publisher of the conservative national newspaper

Sankei

, a major mouthpiece for the revisionist position). Nishio's book became an immediate bestseller. For an incisive introduction to these groups and activities, see Gavan McCormack's essay on “The Japanese Movement to âCorrect' History,” in Hein and Selden,

Censoring History

.

7

. These “typologies” are, of course, open-ended. Space permitting, it would have been fruitful to explore at least two other “kinds of memory” here. One is the manner in which “national memory” is

doubly

mediated and manipulated by others (how Chinese and Americans, for example, tend to set simplistic negative renderings of the situation in Japan against equally selective positive constructions of their own history and contemporary collective mind-set). The other might be called, in the Japanese case, “legally suffocated memory” (referring specifically to the manner in which official fears of costly lawsuits have prompted the Japanese government to dismiss current individual claims for redress and reparations). For a recent study of war memory sensitive to the approaches of contemporary critical theory, see Yoshiyuki Igarashi,

Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945â1970

(Princeton University Press, 2000). I address the multiple memories associated with just the atomic-bomb experience in chapter 5 in this present volume.

8

. A high point in the revisionist campaign to promote a “correct” view of history occurred in early 2001, when the conservative activists succeeded in gaining certification of a middle-school history textbook

reflecting their position. To gain such certification, the publisher and authors agreed to some 137 large and small changes. Among the more revealing of these was a passage in the epilogue that originally read as follows: “After the war (in which as many as 700,000 civilians were killed in indiscriminate bombing, culminating in the atomic bombs), the direction the country should take was determined by the Occupation force, and Japan has remained under this influence to the present day. . . . Regrettably, the scars of defeat have not healed after more than fifty years. Because of this, the Japanese are on the verge of losing their independent spirit.” In the version approved by the central government, this was revised as follows: “As many as 700,000 civilians were killed in indiscriminate bombing, culminating in the atomic bombs. After the war, the Japanese people, through great effort, achieved economic recovery and attained a position among the world leaders, but in spite of this they still lack self-confidence. . . . Regrettably, the scars of defeat have not healed.” The controversy concerning this textbook (and a companion “civics” volume) is covered in considerable detail in

Asahi Shimbun

, April 4, 2001.

9

. I have discussed the problems of the Tokyo trial at length in chapter 15 of my

Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II

(W.W. Norton and The New Press, 1999). The most dramatic recent use of Pal's dissenting opinion by the conservative revisionists took the form of a slick 1998 feature film titled

Pride: The Fatal Moment (Puraidu: Unmei no Toki

). Conceived and promoted by prominent conservatives, and funded by a nationalistic entrepreneur, this was a courtroom drama that re-created the physical setting and

defense

arguments of the Tokyo trial with considerable skill. Although former general and prime minister T

Å

j

Å

Hideki, the trial's best-known defendant, emerges as a flawed leader but humane and sincere victim of “victor's justice,” the elegant and irreproachable hero of the film is Justice Pal himself.

Pride

is a dishonest film (its treatment of atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking, for example, is reprehensible), but its presentation of half-stories and half-truths is exceedingly clever.

10

. “The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II” is the subtitle of Iris Chang's phenomenal international best-seller,

The Rape of Nanking

(Basic Books, 1997). In Japan, such rhetoric and the broader flawed analogies that lie behind it (compounded by a number of petty factual errors in this particular case) has turned what could have been a persuasive indictment of Japanese war behavior into a perfect straw man for those who argue that Japan's critics have no interest in even getting the

facts straight. Substantial right-wing money has been poured into attempts to counter Chang's indictment in English-language publications distributed gratis outside Japan. See, for example, Takemoto Tadao and Ohara Yasuo,

The Alleged âNanking Massacre': Japan's Rebuttal to China's Forged Claims

(Meiseisha, 2000); Tanaka Masaaki,

What Really Happened in Nanking: The Refutation of a Common Myth

(Sekai Shuppan, 2000); and Hata Ikuhiko, “Nanking: Setting the Record Straight,”

Japan Echo

25, no. 4 (August 1998).