Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

What Hath God Wrought (32 page)

Besides carrying goods and passengers, ocean vessels also hunted whales and fish. For two decades beginning in 1835, four-fifths of the world’s whaling ships were American. New Bedford, Massachusetts, dominated American whaling (as Nantucket had done in the eighteenth century). The demand for whale oil, used for lighting, increased as more people left the farms and moved to cities. Other whale products included whalebone, used much as we use plastic; ambergris, used in perfume; and spermaceti, used as candle wax. In sharp contrast to textiles, whaling ships employed an all-male labor force. The historian William Goetzmann has aptly called the bold navigators who added to geographical knowledge in their pursuit of the leviathan the “mountain men of the sea.” The forty years beginning in 1815 represented the golden age for the American whaling industry; its fleet peaked at mid-century, just before the new petroleum industry began to replace whale oil.

38

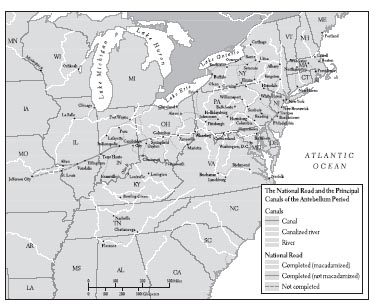

Canals further extended the advantages of water transport. Canals might connect two natural waterways or parallel a single stream so as to avoid waterfalls, rapids, or obstructions. Locks raised or lowered the water level. Horses or mules walking along a towpath moved barges through the canal; an animal that could pull a wagon weighing two tons on a paved road could pull fifty tons on the towpath of a canal.

39

In Europe, canals had been around a long time; the Languedoc Canal connected the Mediterranean with the Bay of Biscay in 1681. In North America, canal construction had been delayed by the great distances, sparse population, and (embarrassing as it was to admit) lack of engineering and management expertise.

40

During the years after 1815, a society eager for transportation and open to innovation finally surmounted these difficulties. Because canals cost more to construct than turnpikes, public funding proved even more important in raising the capital for them. Energy and flexibility at the state level got canal construction under way when doubts about constitutional propriety made the federal government hesitate. Many canals were built entirely by state governments, including the most famous, economically important, and financially successful of them all, the Erie Canal in New York.

41

Astonishingly, this ambitious artificial waterway from Albany to Buffalo was completed in eight years. On October 26, 1825, Governor DeWitt Clinton boarded the canal boat

Seneca Chief

in Lake Erie and arrived at Albany a week later, having been cheered in every town along the way. He then floated down the Hudson to New York harbor, where, surrounded by a flotilla of boats and ships of all kinds, he poured a keg of Lake Erie water into the Atlantic. On shore, the city celebrated with fireworks and a parade of fifty-nine floats. The canal had contributed mightily to the prosperity of New York City (which in those days meant simply Manhattan). Even the urban artisans, who had originally opposed it in fear of higher taxes, had become enthusiastic about the Erie Canal. Because it facilitated transshipment of goods from New York City inland, the canal encouraged the extraordinary growth of the port of New York. One day in 1824 some 324 vessels were counted in New York harbor; on a day in 1836 there were 1,241.

42

The Erie Canal’s effects elsewhere were at least as dramatic as those in New York City. Across western New York state, construction of the canal mitigated the hard times following the Panic of 1819, and its operation stimulated both agriculture and manufacturing. The Erie Canal made New York the “Empire State.” Within nine years, the $7,143,789 it had cost the state to construct the canal had been paid off in tolls collected; by then its channel was being expanded to accommodate more traffic.

43

The canal initiated a long-term boom in the cities along its route, including Albany, Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo. Between 1820 and 1850, Rochester grew in population from 1,502 to 36,403; Syracuse, from 1,814 to 22,271; Buffalo, from 2,095 to 42,261.

44

The canal transformed the quality as well as the quantity of life in western New York state. Where earlier settlers had been to some extent “self-sufficient”—eking out a subsistence and making do with products they made themselves or acquired locally—people now could produce for a market, specialize in their occupations, and enjoy the occasional luxury brought in from outside. When fresh Long Island oysters first appeared on sale in Batavia, a western New York town, it made headlines in the local newspaper. The cost of furnishing a house fell dramatically: a clock for the wall had dropped in price from sixty dollars to three by midcentury; a mattress for the bed, from fifty dollars to five. Although some of this saving was due to mass production, much of it was due to lower transportation costs.

45

Changes from the rustic to the commercial that had taken centuries to unfold in Western civilization were telescoped into a generation in western New York state. While some people moved to cities, other families moved to new farms where they could maximize their contact with markets. The value of land with access to transportation rose; that of farmland still isolated fell. The social and cultural effects of these changes were particularly felt by women, causing some to turn from rural household manufacturing to management of middle-class households based on cash purchases.

46

The religious revivals of the burned-over district reflected in part a longing for stability and moral order amidst rapid social change. They began with efforts to tame the crudity and vice of little canal towns and went on to bring a spiritual dimension to the lives of the new urban middle and working classes.

Meanwhile, by the shores of the Great Lakes, the canal facilitated the settlement of northern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois by people of Yankee extraction moving west by water and sending their produce back east the same way. Without the canal, the pro-southern Butternuts would have dominated midwestern politics, and the river route down to New Orleans would have dominated the midwestern economy.

47

Canals were more exciting for shippers and engineers than for passengers. Long-distance travel by canal boat proved effective in moving large numbers of people, but it was not much fun. The speed limit on the Erie Canal was four miles an hour, and travelers like the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne commented on the “overpowering tedium” of the journeys. Catherine Dickinson of Cincinnati, the aunt of Emily Dickinson, complained like many others of sleeping quarters so “crowded that we had not a breath of air.” Still, canal travel was safe and suitable for families, and passengers relieved their boredom with singing and fiddles. Harriet Beecher Stowe summed it up: “Of all the ways of travelling, the canal boat is the most absolutely prosaic.”

48

Others rushed to imitate New York’s canal success. Ohio complemented the Erie Canal with a system of its own linking Lake Erie and Cleveland with the Ohio River and Cincinnati. The canals brought the frontier stage of Ohio history to a rapid close and integrated the state into the Atlantic world of commerce.

49

The Canadians constructed the Welland Canal, bypassing Niagara Falls for vessels going between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Pennsylvania undertook the most extensive canal system of any state. Jealous of New York City, Philadelphia businessmen wished to expand their own city’s commercial hinterland beyond the 65-mile-long Lancaster Turnpike. A group of them led by Matthew Carey persuaded the Pennsylvania legislature to commence in 1826 the Mainline Canal, going all the way to Pittsburgh and the Ohio River. The Mainline Canal was an even more impressive engineering feat than the Erie: 395 miles long, it rose 2,322 feet over the Alleghenies and had 174 locks and an 800-foot tunnel.

50

Its backers hoped that the Mainline Canal would compete successfully with the Erie because, being farther south, it would be blocked by ice for a shorter time in winter. But inevitably, it cost more time and money to surmount Pennsylvania’s more formidable geographical barriers, and the planners of the Mainline Canal compounded their difficulties by dissipating resources on too many feeder canals. As a result, Pennsylvania’s canal system came into operation just a little too late. The advent of a startling new technology spoiled the hopes of the state’s canal builders. When the Mainline Canal finally linked Philadelphia with Pittsburgh in 1834, it included a railway portage over the crest of the mountains. By this time it was clear that it would have been more efficient to build a railroad all the way. The Mainline Canal’s advocates had not wanted to wait for railway technology to develop, so they pressed ahead with a program that quickly became obsolescent.

51

In transportation projects, as in love and war, timing was critical.

Yet even internal improvements that did not earn a profit for their owners could still be economically valuable to their region by lowering shipping costs. Improved transportation made a big difference to daily life in rural America. Not only could farmers sell their crops more readily, they could also buy better implements: plows, shovels, scythes, and pitchforks, now all made of iron. Even sleighs with iron runners became available. Clothing and furniture could be purchased instead of homemade. Information from the outside world was more readily available, including advertisements that told of new products, helpful or simply fashionable. As early as 1836, the

Dubuque Visitor

, far off in what is now Iowa (then part of Wisconsin Territory), advertised ready-made clothing and “Calicoes, Ginghams, Muslins, Cambricks, Laces, and Ribbands.” And instead of bartering with neighbors or the storekeeper, rural people increasingly had cash to facilitate their transactions.

52

Did internal improvements benefit everybody? No. Sometimes local farmers or artisans went bankrupt when exposed to the competition of cheap goods suddenly brought in from far away. Northeastern wheat-growers were hurt once the Erie Canal brought in wheat from more productive midwestern lands. Some of them could switch from grains to growing perishable vegetables for the nearby cities, but others had to abandon their farms. Generations later, travelers could find the ruins of these farmhouses among the woods of New England. Before the great improvements in transportation, such farms, however inefficient on their infertile and stony soil, could yield a living producing for a nearby market. There were also people, mostly in the South, who didn’t expect to use internal improvements and therefore didn’t want to have to pay for them. These included not only the lucky owners of farms or plantations located on naturally navigable waterways but also subsistence cultivators who were almost self-sufficient, perhaps supplementing what they grew by hunting and fishing as their Native American precursors had done. If these people felt content with their lives—as some of them did—they would not care to have internal improvements changing things. Similarly isolated were certain ethnic enclaves in the North such as the Pennsylvania Amish, whose members traded little and mainly within their own community. People like that could afford to be indifferent to internal improvements. But the lives of most Americans were powerfully affected, and usually for the better.

Finally, internal improvements could be opposed for reasons that had nothing to do with their economic effects. There were those who felt their stake in the status quo threatened by any innovation, especially innovation sponsored by the federal government. All slaveholders did not feel this way, as Clay and Calhoun clearly demonstrated, but some did. North Carolina’s Nathaniel Macon confided their fears to a political ally in 1818: “If Congress can make canals, they can with more propriety emancipate.” Northern enthusiasm for internal improvements needed to be checked, he cautioned. “The states having no slaves may not feel as strongly as the states having slaves about stretching the Constitution, because no such interest is to be touched by it.” The strident John Randolph of Roanoke made this logic public: “If Congress possesses the power to do what is proposed in this bill,” he warned in 1824 while opposing the General Survey for internal improvements, “they may emancipate every slave in the United States.”

53

Men like Macon and Randolph were willing to block the modernization of the whole country’s economy in order to preserve their section’s system of racial exploitation. Clay made the opposite choice, and for the time being he could count on the trans-Appalachian West, free and slave states alike, to back internal improvements. Calhoun, however, was about to change his mind.

III

As part of the celebration of the Erie Canal’s completion, cannons were placed within earshot of each other the entire length of its route and down the Hudson. When Governor Clinton’s boat departed from Buffalo that October morning in 1825, the first cannon of the “Grand Salute” was fired and the signal relayed from gun to gun, all the way to Sandy Hook on the Atlantic coast and back again. Three hours and twenty minutes later, the booming signal returned to Buffalo.

54

Except for elaborately staged events such as this, communication in early nineteenth-century America usually required the transportation of a physical object from one place to another—such as a letter, a newspaper, or even a message attached to the leg of a homing pigeon. This was how it had been since time immemorial. But as transportation improved, so did communications, and improved communications set powerful cultural changes in motion.