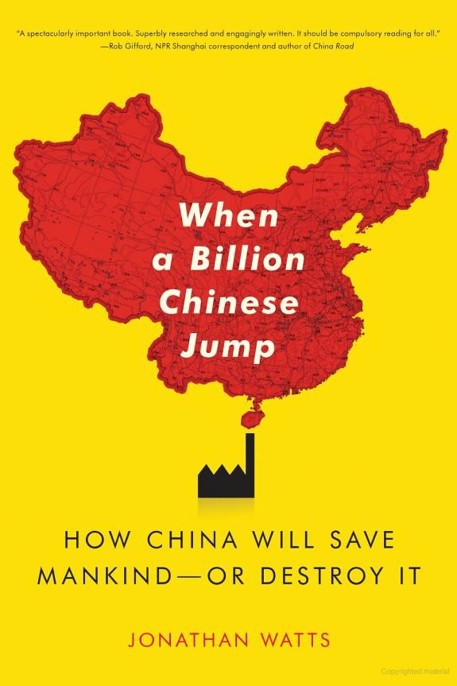

When a Billion Chinese Jump

Read When a Billion Chinese Jump Online

Authors: Jonathan Watts

Tags: #Political Science, #General, #Public Policy, #Environmental Policy

Praise for

When a Billion Chinese Jump

“This is the book on China and climate change that the West has been waiting for. Watts uses his long experience of China to track the country’s environmental calamity up close, uncovering its causes, its contradictions and its shocking human toll. Then he poses perhaps the most seminal question of all—can it save itself and, by extension, the planet?”

—James Kynge, author of

China Shakes the World

“The world’s chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change rests in large part with decisions being made today in Beijing. If China raises its standard of living to Western standards without controlling the emissions from industry and power plants, it will wreak havoc with the world’s climate—with unforeseeable and irreversible consequences. If it takes the road now opening up to a low-carbon economy and leads the world in developing and deploying clean energy technologies, it can show the way to a sustainable future for the planet. Jonathan Watts turns a keen eye on China’s choices—previously made and yet to come—that will affect us all.”

—Timothy E. Wirth, president, United Nations Foundation

and Better World Fund

“Jonathan Watts brings us up to date on China’s economic miracle and the environmental consequences not only for China but for the entire world. With wonderful travelogue-like writing, Watts takes us on an incredible journey through today’s China—and our tomorrow.”

—Lester R. Brown, president of Earth Policy Institute and author

of

Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization

“This is the environmental book that I am most looking forward to for 2010. I admire Jonathan Watts for his rigorous approach to journalism and his devotion to human stories at the grass roots.”

—Ma Jun, founder of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs and author of

China’s Water Crisis

“A fascinating, engaging, and beautifully written book. Jonathan Watts shines a light onto an issue that affects us all but of which we are woefully ignorant. This book succeeds in both informing and entertaining us. It is a masterpiece.”

—George Monbiot, author of

Heat: How to Stop the Planet from Burning

“This is a spectacularly important book, superbly researched and engagingly written. Jonathan Watts has given us a shocking eyewitness account of China’s environmental meltdown. It should be compulsory reading for all.”

—Rob Gifford, NPR Shanghai correspondent

and author of

China Road

“Watts has written a nationwide audit of where China’s environment stands as of the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. His eyewitness accounts are the great strength of this important book.”

—Kerry Brown,

Times Higher Education

(UK)

“An excellent read. A few good gags in it, too, something few writers on China dare ever to try.”

—Paul French, author of

Through the Looking Glass:

China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao

“Meticulously documented, wide-ranging account … this is a revealing and depressing book. There is no ‘middle truth’ in it. During his painstaking investigative journeys, which called on all his powers as a top-class reporter, Jonathan Watts concluded that ‘China has felt at times like the end of the world.’”

—Jonathan Mirsky,

Literary Review

(UK)

SCRIBNER

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2010 by Jonathan Watts

Maps © András Bereznay

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Faber and Faber Limited

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in

any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner trade paperback edition October 2010

SCRIBNER

and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under

license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon &

Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more

information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at

www.simonspeakers.com

.

Designed by Carla Jayne Jones

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010029901

ISBN 978-1-4165-8076-8

ISBN 978-1-4391-4193-9 (ebook)

To Aimee, Emma, and Murray

2 Foolish Old Men—The Tibetan Plateau

3 Still Waters, Moving Earth—Sichuan

4 Fishing with Explosives—Hubei and Guangxi

6 Gross Domestic Pollution—Jiangsu and Zhejiang

7 From Horizontal Green to Vertical Gray—Chongqing

9 Why Do So Many People Hate Henan?—Henan

10 The Carbon Trap—Shanxi and Shaanxi

11 Attack the Clouds! Retreat from the Sands!—Gansu and Ningxia

12 Flaming Mountain, Melting Heaven—Xinjiang

13 Science versus Math—Tianjin, Hebei, and Liaoning

14 Fertility Treatment—Shandong

15 An Odd Sort of Dictatorship—Heilongjiang

Beijing

As a child, I used to pray for China. It was a profoundly selfish prayer. Lying in bed, fingers clasped together, I would reel off the same wish list every night: “Dear Father, thank you for all the good things in my life. Please look after Mum and Dad, Lisa (my sister), Nana, and Papa, Toby (my dog), my friends (and here I would list whoever I was mates with at the time), and me.” After this roll call, the sign-off was usually the same. “And please make the world peaceful. Please help all the poor and hungry people, and please make sure everyone in China doesn’t jump at the same time.”

That last wish was tagged on after I realized the enormousness of the country on the other side of the world. For a small British boy growing up in a suburb of an island nation in the 1970s, it was not easy to grasp the scale of China. I was fascinated that the country would soon be home to a billion people.

1

I loved numbers, especially big ones. But what did a billion mean? An adult explained with a terrifying illustration I have never forgotten. “If everyone in China jumps at exactly the same time, it will shake the earth off its axis and kill us all.”

2

I was a born worrier and this made me more anxious than anything I had heard before. For the first time, my young mind came to grips with the possibility of being killed by people I had never seen, who didn’t know I existed, and who didn’t even need a gun. I was powerless to do anything about it. This seemed both unfair and dangerous. It was an accident waiting to happen. Somebody had to do something!

Life suddenly seemed more precarious than I had ever imagined. In variations of my prayer, I asked God to make sure that if Chinese people

had to jump, they only did it alone or in small groups. But in time, my anxieties faded. With all the extra maturity that comes from turning six years old, I realized it was childish nonsense.

I did not think about the apocalyptic jump again for almost thirty years. Then, in 2003, I moved to Beijing, where I discovered it is not only foolish little oiks who fear China leaping and the world shaking. In the interim, the poverty-stricken nation had transformed into an economic heavyweight and added an extra 400 million citizens. China was undergoing one of the greatest bursts of development in history and I arrived in the midst of it as Beijing prepared for the 2008 Olympics.

The city’s transformation was vast and fast. Down went old

hutong

alleyways, courtyard houses, and the ancient city walls. Up rose futuristic stadiums, TV towers, airport terminals, and other monuments to modernization. Restaurants and bars one day were piles of rubble the next. Tens of thousands of old walls were daubed with the Chinese character

chai

(demolish). The hoardings around a nearby development site were decorated with giant pictures of the old city and a half-mocking, half-mournful slogan: “Our old town: Gone with the wind.”

Living amid such a rapidly shifting landscape, it was hard to know whether to celebrate, commiserate, or simply gaze in awe. The scale and speed of change pushed everything to extremes. On one day, China looked to be emerging as a new superpower. The next, it appeared to be the blasted center of an environmental apocalypse. Most of the time, it was simply enshrouded in smog.

Soon after arriving, I walked home before dawn one morning in a haze so thick I felt completely alone in a city of 17 million people. The milky white air was strangely comforting. Skyscrapers had turned into thirty-story ghosts. The world seemed to have vanished. Yet it was also being remade. Overhead, cranes loomed out of the mist like skeletal giants.

Over the following years, the crane and the smog were to become synonymous in my mind with the two biggest challenges facing humanity: the rise of China and the damage being wrought on the global environment. The builders were constructing the most spectacular Olympic city in history. The chimney emissions and car exhausts were destroying the health of millions and helping to warm the planet as never before.

The year after my arrival, China’s GDP overtook those of France and Italy. Another year of growth took it past that of Britain—the goal that

Mao Zedong had so disastrously set during the Great Leap Forward fifty years earlier. From 2003 to 2008, China stopped receiving aid from the World Food Programme and overtook the World Bank as the biggest investor in Africa. Its foreign-exchange reserves surpassed those of Japan as the largest in the world. The former basket-case nation completed the world’s highest railway, the most powerful hydroelectric dam, launched a first manned space mission, and sent a probe to the moon.

This was a period in which the population increased at the rate of more than 7 million people per year, when more than 70 million people moved into cities, when GDP, industrial output, and production of cars doubled, when energy consumption and coal production jumped 50 percent, water use surged by 500 billion tons, and China became the biggest emitter of carbon in the world.

3

As a parent, I worried for my two daughters’ health when the air became so bad that their school would not let pupils out at break times. I feared too for my lungs. A regular jogger since my teens, I found myself wheezing and puffing after even a short run. When the coal fires started burning each winter, I suffered a dry, rasping cough that sometimes left me doubled up. In Beijing I was to suffer two bouts of pneumonia and, for the first time in my life, I was prescribed a steroid inhaler. The city was choking and so was I.

To be in early twenty-first-century China was to witness the climax of two hundred years of industrialization and urbanization, in close-up, playing at fast-forward on a continentwide screen. It soon became clear to me that China was the focal point of the world’s environmental crisis. The decisions taken in Beijing, more than anywhere else, would determine whether humanity thrived or perished. After I arrived in Beijing, I was first horrified at the chaos and then excited. No other country was in such a mess. None had a greater incentive to change.